Abstract

An unparalleled struggle has been witnessed among the urban women informal workers of Midnapore and Kharagpur cities in West Bengal, India. Many researchers have advocated and are advocating about the deadly impact of COVID-19 pandemic situation on the women informal workers but very few were concentrated on their coping capabilities. These women in the study area have set an example before others that how can one survive her livelihood in the time of critical situation. Despite all the hardships they have been fighting their own lonely battle not only against this situation but also a lot of serious threats like insecurity, low resources and low standard of living. This study mainly highlights the measures taken by these poor women to cope with this situation for the survival of their families along with the external supports provided for them. This is strictly a perception based study conducted among 500 women selected by purposive sampling procedure across age, ethnicity, income and educational level during unlock phases with the help of semi-structured and open ended questionnaire schedule. The result reveals that although their capabilities and efforts to cope with this devastating situation are praiseworthy but it is a hard reality that this pandemic put its evil imprint in every step of their daily livelihoods. The various measures have already been taken by the government but, these measures have to be continued till the situation will become normal along with gender sensitive long term benefit.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The high rate of unemployment in an economically backward region like Midnapore and Khargpur has pushed the poor people into informal employment for survival both rural and urban situation (Bertulfo, 2011). The term ‘Informal Sector’ was first coined by Keith Hart (1973). He defined informal sector where employment opportunities is beyond large scale commercial enterprises, factories or government services. He also differentiates formal and informal earning opportunities depending on wage employment or self-employment.

People engaged in this sector are usually designated as ‘working poor’ because the earning of enough money to live a standard living is not possible from this sector. A huge proportion of women are engaged in informal sectors at Midnapore–Kharagpur municipal regions of Paschim Medinipur district, which are one of the economically backward regions of West Bengal, India. This sector is the only space for the poor people of these regions because they can take entry with minimum or no investment (Jennings, 1994, 2013).

The Indian Government took a sudden decision to impose a complete lockdown of all economic activities for the whole nation on 24th day of March 2020, which was a shocking 4-h notice. Lockdown was implemented because novel coronavirus has already punched in Europe and positive cases continue to rise while the health infrastructural system of India was not well equipped for a battle with unknown nature of such deadly virus. Moreover, it was not sure that a vaccine will be found soon. Thus, lockdown was the best strategy for the government for effective preparedness to defend such crisis. This imparted a devastating impact on the labour market resulted the immediate decrease in employment rate, particularly in informal sectors. The unemployment rate was jumped to more than 23% in India in the months of April and May. It was estimated as three times more than in 2019 (Vyas, 2020). All economic activities had been shut down all of a sudden. This resulted a devastating impact on women in the informal sector. In India, it has been estimated that about 400 million workers in this sector are at high risk of creeping poverty due to COVID-19 pandemic (ILO, 2020a, 2020b, 2020c). The impact of this pandemic is severely visualized on women’s employment as well as their family lives because of their engagement of large number to this sector.

The vast majority of people of the study area are also employed informally. They do not get any job contract, not receive their payment regularly. They are frequently employed as casual labour engaged by middle-men or contractors or agencies. It has been claimed that various attempts had already made to register these informal workers, but the reality speaks another truth. The major portions are not documented till now. Due to this they are not included in the Covid-19 relief schemes, particularly for urban workers.

So, the vital question is that how do these women workers survive, what do they eat, how do they pay for rent and utilities? For searching the answer the present survey has been conducted on urban women informal workers across various sectors in two municipal areas of Midnapore and Kharagpur cities as much as possible. It has been seen that above all facts discussed above are absolutely true and applicable to this region. But surprisingly, an unparalleled silent struggle has been found among women workers in these study areas. Beside all these hardships they have survived and are surviving till now. Despite very meager exceptions, the workers were able to find out the measures of survival. Obviously it is not possible through a magic or any supernatural blessings. It is possible due to their exceptional dynamicity, severe hard work, and socio-cultural set up of the towns, community supports and services, administrative help. Presently, they set up an example before others that how one can survive his/her livelihood in the time at devastating situation. Actually, the poor women workers do not want charity or relief. What they want is work. In true sense work is a healer for them. They are able to build their own ways out of this difficulty too. Too many researchers have already told about the severe impact of COVID-19 pandemic situation on informal workers. It’s really a hard truth that this sector is worst affected and the down trodden section who lives in hand to mouth in the society depends on it. The situation of urban women informal workers is more devastating due to their limited access to resources.

Keeping all the above facts in mind the specific objectives set for this study are, (i) to investigate the hardships faced by these poor urban women informal workers in both lockdown and unlock phases; (ii) to analyze their struggle for existence in the market economy; (iii) to find out the measures taken by them to fight against this deadly pandemic situation for the survival and resilience to themselves as well as their families; (iv) to assess the roles played by the administration of all levels, NGOs, local communities for their survival; and lastly, (v) to find out the pathways and establish the sustainable outline cum approach for socio-economic sustainability and resilience to these poor urban women workers.

Literature review

System of National Accounts (1993), identify informal sector where an individual or group of individuals engaged in production of goods or services typically for employment and generation. Nature of employment in this sector is casual rather than contractual or with any formal guarantee. Informal workers also comprise who worked in household enterprises or in equivalent enterprises.

Informal sector has been defined in 15th International Conference of Labour Statisticians (1993), at ILO as a mass of people who engaged in production units basically owned by household or household enterprise, including self-employment and employers who engaged in small and non-registered enterprises.

The 17th International Conference of Labour Statisticians (2003) at ILO sets some criteria to define informal employment in its guidelines. These includes, any ‘remunerative employment’ i.e. wage employment and self-employment which is not registered or regulated by legal bodies and workers who are engaged in the informal sector doesn’t enjoy social security, employment guarantee and workers benefit as well.

Two basic criteria for identification of informal sector has been adopted by The National Sample Survey Organization (NSSO) (2001a), while conducting survey on workforce of unorganized sector. These are- (i) any manufacturing industry covered under Annual Survey of Industries (ASI) shall not be considered as unorganized sector and vice-versa. (ii) In service sector, any enterprise which is not run by the Government (Central, State and Local Body) shall be treated as unorganized sector. This sector is also the most easily accessible for women to overcome the under employment and unemployment by creating their own sources of income along road side vending, hawking or working in the domestic sphere. Although all these activities are exposed to financial, social, and health risks within the informal economy, but they have to concentrate on these low status jobs with high vulnerability to poverty due to their access to limited resources. (Kasseeah & Tandrayen-Ragoobur, 2014). The majority of men are engaged in informal economy rather than the women in the world, but in India this picture is just the opposite. Here, women are engaged more in number in these sectors than men (Bonnet et al., 2019).

The lockdown had been triggered in India in four phases, when the livelihoods of these poor women were in peril and, in six unlock phases they were just confused and disoriented (Chakraborty, 2020; Kesar et al., 2020). The lockdown and unlock phases in 2020 are mentioned in the Table 1.

These consecutive lockdowns and unlock phases were just adding the humiliation to the wound of the people engaged mainly in informal sectors throughout India for out migration. They were forced to leave urban centers due to eviction of rented houses, loss of livelihood and starvation (Yadav, 2020). Urban informal women workers across various sectors are not able to pay rent or know where their next meal would come from in the lockdown periods (Delany, 2020).The pandemic actually opens the eyes of policy makers about the vulnerability and challenges exist within this sector and the workforce too (Patel, 2021).One ray of hope was applicable particularly in the study area that this region did not face such a devastating reverse migration. In the meantime, women are disproportionally shouldering the responsibility to support families and communities to survive.

It has been evidenced that, the economic as well as productive lives of women are differently and disproportionately affected rather than men’s lives due to this COVID-19 (Grown & Sánchez-Páramo, 2020; UN, 2020). Women informal workers have been worst affected (Banerjee, 2020). For them, survival has become a big question in such a turbulent time. Due to the slowdown of all forms of employment opportunities the management of livelihoods of these poor women informal workers just becomes impossible, particularly in urban areas where the cost of livelihood is greater than rural areas. The intake of nutritious food by the entire family has been dropped that means the access to nutritious food taken by women has also dropped because all know ‘women are the last to eat and they eat the least’ (Nanavaty, 2020).

Working women in this sector are recognized as the people of low socio-economic status at Mdnapore and Kharagpur municipal areas. They have low literacy status, low status of employment, lack of capital resource and a poor standard of living. Generally, they don’t know as such about the market and mostly dependent on market agents. Most of these women have no legal protection. They usually like to do work in domestic sphere, such as, daily wage workers, paid per unit, street vendors, family business, domestic workers, self-employed and casual workers (UN Women, 2016). These women usually accept such jobs because they have no such alternative. As the society of this study region is rather old fashioned and traditional so, that there are strong rigid socio-cultural constraints, which poses restriction to their mobility to take jobs outside the home. The surprising fact is that more than 25.2% among these informal workers are widows or left by their husband leaving two or more children in their wives’ shoulder and for this they have to struggle for their family survival (Table 2).

Women have hit the hardest, because they are overrepresented in the most precarious jobs like street vending, waste picking, home-based work, construction, domestic jobs, beauty parlours and gyms, head-loaders and other short-term contracts (Jadhav, 2020; Srivastava, 2020). They mostly belong to below poverty line, and are undocumented to qualify for government aids of both financial and non-financial, particularly to this pandemic situation. They are not registered to avail the benefits of the social security net schemes. These workers often are excluded from relief efforts because they are invisible to governments, Non-Government Organizations (NGOs) and relief agencies due to the lack of data. This “formal invisibility” should be addressed in urgent basis (Hamilton, 2020).

This fact is a hard truth found in the study area where, a large number of informal workers are unregistered, and it was severely true among women workers. For this, they can not avail the benefits of government relief packages.

An important survey has been conducted on the impact of COVID-19 among self-employed, casual and regular wage women workers across 12 Indian states (Lahoti et al., 2020). It reveals that women workers are at a higher risk of food insecurity as compared to men. Another survey by Action Aid (Sapkal et al., 2021) reveals that the loss of employment is more among women than men. About 90% of women with paid employment are in the informalsector. More than 52% women workers lost wages due to non-payment in the initial phases of the lockdown in India (mid-March–May 2020), which led to a loss in savings at the household level leaving women workers more vulnerable. A greater demand for new rules of labour rights with new amendments to labor codes in favour of these workers in informal sectors have raised (Das et al., 2015; Magazine, 2020).

The women have already less access to credit, land, technology, less savings than men, as well as less network of opportunities and less decision-making power (WIEGO, 2020a).Huge number of women are engaged in this sector for the survival of their families. Sometimes they earn more money than their male counterpart. Some studies argued that pandemic open up new employment opportunities for women which acts like a ray of hope in such hard time (Seibert et al., 2013; Zikic & Richardson, 2007). Moreover, the saddest side of informal sector is that they have to suffer a lot by some serious threats like insecurity, eradication issue, low income, e-shopping, shopping malls and a low standard of living. They can't even enjoy minimum market amenities and are totally unaware about different health and insurance schemes which makes them more vulnerable.

Study area

Midnapore and Kharagpur are the two most important adjoining urban areas of West Bengal. The astronomical location of Midnapore is 22°42ʹ N and 87°32ʹ E whereas Kharagpur is 22°32ʹ N and 87°32ʹ E (Fig. 1). Midnapore is the district headquarters of Paschim Medinipur district of West Bengal located on the left bank of the Kangsabati River (also known as Kasai or Cossye), the life line of both the cities. Midnapore city is basically an administrative town with several educational institutions of academic, professional and technical fields. People are mainly engaged in service sectors. Besides the local permanent residents thousands of outside students and people stay here and migrate in daily basis. On the other hand, Kharagpur city is a multicultural, populated, and a cosmopolitan city of this district based on industrial and service economy (Census of India, 2011). A large flow of short term and daily labour is found here. Both these cities characterize faster growth rate of population. Eventually these are dependent on urban informal workers in markets, offices, industries, hotels, hostels, messes and, homes. Not surprisingly, a major portion of these informal workers is constituted by women in these areas. The demand of low priced and easily available foods and services are fulfilled only by these sectors.

The primary population statistics of these two cities are given in the Table 2 in which it has been evident that the population density is much higher in two cities, but it is extreme in Midnapore city (9068/sq. km) mainly because of administrative and educational benefits. The literacy rate is very satisfactory. Sex ratio is also not bad as compared to West Bengal State average of 950 (Census of India, 2011). But, the working status of both the cities is just frustrating. The devastating scenario has been found in the case of female work participation rate. Only 11.76 and 3.44% women in Midnapore and, 8.70 and 5.51% women in Kharagpur are engaged as main and marginal workers. More than 80% women are recorded as non-workers in both cities (Table 2). Here, lies the hidden truth. These recorded women non-workers are not at all unemployed. Most of them are engaged in various unorganized informal sectors which have not yet been recorded or registered as workforce and excluded from various government welfare schemes. These women actually serve the city and run the city.

Research methodology

The cause for the selection of Midnapore and Kharagpur cities as the study area is the dependency of economy on informal sector. The target groups of this study are the urban women informal workers who have a major contribution in family survival across age, ethnicity, marital status, education, family size and migration status. Their struggle against this deadly pandemic situation is the main focus of this study. The sample size of respondents is 500 equally distributed to both the cities. The selection criteria of sample respondents are discussed below.

First of all, five key informants who had profound knowledge about what is going on in their areas were identified from local communities. For the selection of sample respondents the purposive sampling technique, a non-probabilistic sampling method had been used because, the present research needed the diverse as well as expert respondents (Palinkas et al., 2015; Patton, 2014).

The survey has been done in three phases, such as i. 15th–20th June, 2020 (Unlock phase 1.0); ii. 5th–10th August, 2020 (Unlock phase 3.0); iii. 20th–25th November, 2020 (Unlock phase 6.0) with the help of semi- structured and open ended questionnaire schedule of pre-formulated set of questions.

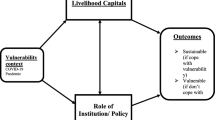

MS Excel and SPSS have been used for data analysis, whereas the qualitative statistics are represented in tables and diagrams by using various cartographic techniques. The location map has been prepared using ARC-GIS software. The updated version of Mishra & Singh (2003); Kumar et al., (2012); Saleem & Jan (2021) of Kuppuswamy’s (1976) socio economic status scale has been followed to identify socio-economic status of the informal workers of study area. This article mainly uses the 2012 updated scale because changes in inflation rate can change the values in monetary terms of the monthly income range scores. It should be noted that before starting the interview process, a discussion session was held with the key informants, elders and people engaged in the local administration to clarify the purpose of this research. This session was very useful to build the confidence level of the female respondents, so that they could be able to give reliable information without any hesitation and suspicion. After this session, the potential willing informants were categorized into various groups. To assess the economical sustainability and resilience like complex matters, and to fulfill the purpose and cross examination of the information, the opinion of the people of different age groups, income status, educational level, occupational structure is necessary. Age had provided the information on generation gap and future prospects, income and occupation had produced the facts of the economy behind this practice, education had bestowed the understanding of knowledge level of the situation rendering a separate outlook about this system (Fig. 2).

Result and discussion

The economic and socio-cultural background of the respondents in this study area is not so much different from other informal workers of other developing countries. The basic characteristics women informal workers in terms of ethnicity, age, educational qualification, family size, migration status, marital status have been enlisted in Table 3.

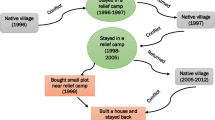

Among the 500 women urban informal workers who were the respondents in the study from Midnapore and Kharagpur cities, 37% belonged to Other Backward Classes (OBC), 24% General, 31% Scheduled Castes (SCs) and 8% Scheduled Tribes (STs) communities. Interestingly, the majority of women urban informal workers are either mid aged or old aged. As per age cohort classification, most of them belonged to 45–55 years (38.9%), 55–65 years (24.4%) and 35–45 years (21.5%). Among the respondents, 21.2% were migrants (coming from nearby rural villages to the town), while the rest (82.8%) were natives. Most of the women workers are married and belonged to the family size of 5–6 usually consist of the husband, wife, two children and/or father and mother-in-laws. It is very unfortunate that half of the respondents replied that their husbands are jobless and they are the principal bread-winner of the family.

It has been also found that almost half of the workforce doesn’t have the qualification above the primary level. These results are in line with Williams & Gurtoo (2011) for India. Illiteracy or low educational qualification is the main barrier for the betterment of them. They didn’t understand the ups and downs of the market properly or couldn’t plan their marketing strategies. Due to such lacking of knowledge they are often exploited by formal sectors. Low educational qualification restricted them to minimum employment opportunities and forced to sustain with minimum income. Only 7% women informal workers are highly educated having graduation. Due to lack of employment opportunities they are forced to adopt such employment mostly to run their families. Thus, the target respondents from backward socio-economic and cultural background have to struggle their own battle for survival.

Socio-economic status

This study tries to find out the socio-economic status of the informal female workers to assess the intensity of vulnerability based on the Kuppuswami scale (revised) in the deadly pandemic situation. It has been derived on the basis of three basic parameters which are income, occupation and educational status of the informal workforce. The result is that most informal female workers belong to lower-middle and upper-lower class. More than half of the workforce is listed under upper lower class or category IV (Table 4). Just imagine that workforce carries either lower- or middle-class status which arises a vital question that how much prosperity they will have to live a well-being life. Such socio-economic status reveals the poor educational attainment of the worker, the low level of income and the low occupational prestige of the entire informal workforce of the study area. All the three pillars of the development are somehow very week among these informal workers and less potential for future development. Thus, the entire workforce belongs under the threats of vulnerable situation.

Women dominating informal sectors

Usually, women informal workers are either self-employed or domestic workers or unpaid/less paid home-based workers (Chen, 2001, 2016; Sumalatha et al., 2021). Self-survival and supporting own family is the sole reason behind the development of women entrepreneurship and self-employment (Gordon, 2000). The male informal workforces are usually either owner operators or paid labourers of informal enterprises while women informal workers are more likely to be own account workers and subcontract workers. Such gender based inequality in workplaces is primarily responsible for relative earnings and increasing poverty levels among genders in informal workforce (Chant & Pedwell, 2008).

The majority of women is self-employed or casual and subcontract workers in various forms of informal sector (Fig. 3). Very few employers hire paid workers. The interesting fact is that most of the female traders tend to deal in food items and to have smaller scale operations (Fig. 4).

Here, it should be pointed out that why women are concentrated in these specific types of sections within the informal sector. The argument is that women are least capable than men to compete in labour, capital, as well as product markets mainly because of low literacy level of women particularly digital literacy and skill. Another observation is that time management and mobility is highly challenging for women workers after fulfilling family demands as social and cultural norms of the family, family responsibilities and low levels of interest in women’s education, training and business (Delaney, 2020).

Challenges faced by the respondents during pandemic.

The respondents faced a wide range of financial and non-financial constraints and obstacles throughout the pandemic period. The major challenges confronting these informal workers depicted in the diagram (Fig. 5). Many informal workers particularly street vendors are always blamed for traffic congestion, making cities filthy, causing air pollution, which always affect town or cities, and thus tagged as a headache to urban administrations as well (Berhanu, 2021). Therefore, such activities recognized as mishap for the public. In words of Palmer (2007), the importance of street vendors in an urban area should not admire in any policy.

In these study areas the women informal workers faced heavy challenges regarding their daily life business. High inflation due to pandemic resulting in high cost of living had created too many difficulties in daily survival. Generally, they lived in rented house in urban slums and remote areas for unaffordability of permanent houses.

The inflation of acquiring goods, unnecessary police harassment, intense competition in the market were the associated major challenges with the shortage of financial growth makes life harder for urban informal workers. Due to lack of principal capital they are unable to expand their business up to the mark. As many of them had no such license so that, they naturally bullied by law enforcers and sometimes this goes beyond rules and regulations and humanity as well.

Dues for poor women informal workers are beyond their affordability, particularly in the period of economic and personal crisis. They also suffered by inadequate staff and space (WIEGO, 2021). Lack of maternity protection also affects mothers’ ability to breastfeed exclusively for a 6-month period and continues breastfeeding to supplement solid foods until children are two years old, as per recommendations of the World Health Organization. Women domestic workers and informal traders were reported working until childbirth and returning in less than 3 months as they need to earn an income (Christiane et al., 2019).

During lockdown no transportation facilities for either go to workplace or to brought commodities to market mostly hampered informal workers (Fig. 6). Many of them who mainly worked in small shops, hotels, entertainment parks have suffered by losing their job due to financial issues of their superior. This is a global phenomenon (ILO, ). These less educated women had faced problems to run the business in online mode due to their digital illiteracy. Socio-cultural and personal securities were other major issues faced by them in the workplace, society and family. They had lack of representation and leadership in the associations and organizations where they could raise their voice for equality. Another major problem is the exclusion of women in social as well as the economic security schemes due to unawareness and non-registration.

Among 360 million only 150 million poor women receives emergency cash transfer from the Government of India through Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojona (PMJDY) (Pande et al., 2020). But this is very unfortunate that almost half of poor women did not receive such benefits as this scheme was only operated through PMJDY accounts.

Thus, in this critical time, all sectors of the market economy has slowed down, a large extent of employment opportunities are eliminated, loss of work, income, abolition of livelihoods and food insecurity makes the life more critical for them.

So, how do these poor informal workers faces these challenges and makes them resilient for such situation? How do they convert their subsistence to sustainable subsistence and reconstruct their life? At this very stage, their struggle for existence begins.

Struggle for existence

This pandemic shook the career for lots of people around the world (Akkermans et al., 2020). This health crisis is now turned into a global financial crisis where job opportunity, income and health of millions of people as well are at risk across the globe. Appropriate containment measures and COVID protocols adopted by majority countries in the first half of 2020 put a substantial break on most socio-economic activities (ILO-OECD, 2020).The people of this study area also faced the evil face of this pandemic. They were shocked initially because suddenly they had found themselves jobless. The situation became terrible among poor women engaged in informal sectors. But gradually they were habituated to cope with this situation. Their adjustability with changing scenario was just surprising. They adopted few measures whatever be accessed by them to fight against this pandemic and ultimately were successfully survived and are surviving till now. The survey registered the following measures taken by these poor urban women.

To shed light on the struggle for existence the study undertook the following measures namely (1) Workless women shifted their occupation to adjust with the changing situation. (2) The free ration, cash in hand, community services of food, clothing, safety measures, health services were and are considered by the respondents as very helpful to survive. (3) Both economic and mental support from the employer especially in lockdown phase played the crucial role in their struggle. (4) Poor women who are considered as the best house manager tried to manage the family expenditure. (5) They survived in such crisis at the cost of their monthly savings to minimize the gap between reduced income and inflated expenditure. (6) They adjusted with the restricted opening and closing timings of the market by giving emphasis on selling priority basis consumer goods. (7) The benefits of various economic and social protection schemes were taken. No such evidences of death due to hunger has been recorded in this study area.

Shifting of occupation

To cope with this hard situation, the jobless women tried to find the alternatives. The evidences of havoc shifting of occupation have been observed. Many housewives (22.4%) whose husbands then lost their jobs due to lockdown were starting to find any kind of work from where they could earn money for their family survival. 11.2% self-employed women have to take the job of casual labour of daily payment basis or give various home services because their own shops were closed due to lockdown. About 10.1% casual workers worked mainly as domestic workers because of the dismissal of their employers. Many street vendors (5%) did the job in nearby villages as agricultural labourers. But the most interesting fact is that about 43% respondents did not change their occupation. Most of them are street vendors of vegetable, fish and other essential commodities which were allowed for vending in restricted timings. Only 8.2% were claimed as jobless (Table 5).

From the qualitative survey the researchers experienced a notable observation that was though pandemic becomes a career shock and negatively impacted, but may bring positive vibes with a new dimension of employment opportunity in due time. Few educated respondents replied the same during the personal interviews. Many who just performed as housewives are now moving on as workers whatever the work is and contribute to their family income. They are now much satisfied rather being a housewife. The study indicated that what had today seemed like disheartening had tomorrow opened new hopes for them which ultimately increased their job-satisfaction and opportunities.

Management of livelihoods

The socio- cultural set up of these two cities allow everyone to be concerned about others. Most of the women claimed that free ration provided by both state and central governments in the Public Distribution System (PDS) and cash in hand from government, NGOs, and personal levels saved their lives. Various initiatives were taken in organizational as well as individual levels to run the community kitchen for supplying cooked food for needy persons during lockdown and even after lockdown phases (Fig. 7). Almost all women managed their household expenses with reduced income. Their savings were almost withered off to meet their needs. About 32.6% respondents seek support and help in cash or kind from their nearest relatives and friends while 46.2% women managed the household expenses by borrowing money from money lenders (Table 6).

Employers support

Because of sudden collapse in employment supply and loss of income, the livelihood of many women informal workers become terrible and due to closure of all income sources or loss of income of other adult male members of the family makes their life worse. This was the time they face the most awful face of poverty.

Many of the workers reported behalf of favourable support from their employers in such difficult time. At the meantime, few workers reported that they had got favourable support from their employers end during this pandemic. These are material support (65.7%), such as, groceries, consolation to re engagement in work when this lockdown shall over (85.2%) and advance salary payment (12%). Another 37% worker claimed that they were frequently asked by their employers about the conditions of workers in regular basis over telephone during lock down and 11.5% also received assurance of salary hike in the future (Table 7).

Management of household expenses

Usually, it is being told that women are the best managers of families and it is better evidenced at the time of deadly pandemic when the families of poor urban women informal workers were on the edge of the ditch. They performed a wonderful job by standing at the back stage of society.

Majority of the women (87.2%) cut off in the use of luxurious consumer goods whatever they accessed. 32% women subscribed only few channels in television (T.V). They (92.8%) used electricity as minimum as possible. Those (57.3%) who did not have free Liquid Petroleum Gas (LPG) connection had to switch on to other less expensive fuel consumption like kerosene, fuel wood and coal (Table 8). Their credentials are great in management of food and medical expenses. Besides 2 or 3 items they cooked one major item out of existing vegetables and tried home remedies to cure common diseases. Classes were held in on line mode and West Bengal Government provided onetime cash of Rupees (Rs.) 10,000.00 (Ten thousand Rupees only) to purchase smart mobile phone for all students to avail online classes. So, no such expense was incurred for educational purpose in lockdown and onwards.

Reduction in monthly income and savings

To understand the household dynamics and livelihood during Pandemic, the nature of household expenditure management, changes in household income, savings and debt, versatile family relationships and long-term and short-term impact on the family were investigated. Beside only 3.4% almost all respondents reported the reduction of income specified in different magnitude (Table 9). The women engaged in domestic services, street stalls and small shops were worst affected in the lockdown period of the first phase. Street vending and vegetable or fish markets were restricted in stipulated timings. In times of no income or the reduction in income, family sustenance was predominantly dependent on using savings or borrowing money from relatives or money lenders.

People always try to make some savings which helps them in the future. It always remains a backup for everyone if any unexpected threats come into life. For this, the present study focuses on the nature of savings by informal workers. This is very unfortunate that a threat for their future has been already assigned as the level of their savings dropped down significantly (Fig. 8). Inflation of all items in the market and reduced income or no income during and post lock down phase forced them to cut off their monthly savings. This is a very common strategy of the poor people which was triggered for their survival in such terrible crisis.

The devastating scenario has been found in the picture of monthly family savings of women workers in this sector. A dangerous gap is found in savings between pre and in-COVID situation due to the depression in business. People are not ready to purchase any street foods. Workers are confined at homes due to series of lockdowns. Domestic workers are not yet welcomed. Purchasing power of people is reduced due to the set back of every sector of the economy.

Adjustment with the market economy

For survival, the urban women informal workers have to adjust with the ups and downs of the market as well as the situation. The COVID-19 pandemic situation teaches a lesson to these women that how they could adjust in every step of their livelihoods.

The opening and closing times of market has been restricted by the administration in the lockdown and unlock phases to limit the spread of this deadly virus. Gradually, these women (76.2%) were habituated with this system. For sale, they (68.6%) emphasized on priority consumer goods. Generally, they are not comfortable with online payment but in this time they have learned and used online payment systems like Bharat Interface for Money (BHIM), Phone Pay, Google Pay and Paytm. About 14.3% women learned the system of digital marketing and the use of online payment mode so that, they could take the order and receive the payment in online. Many women (26.8%) started to supply home delivery of cooked food, vegetables, groceries and medicines. The local residents of both the towns are fully dependent on local urban markets. Therefore, the market is always full of demands. The evidences of supply chain disruption of essential commodities in heavy amount have not been recorded in these areas because the daily basis requirements come from nearby villages. About 43.8% respondents claimed that administration helped them by providing information about market related issues time to time as much as possible they can but 69.5% women blamed police for unnecessary harassment (Table 10). More or less it might be said that the situation of women was not so much severely acute in the market due to their own understanding, cooperation and help.

Social safety net measures

Social safety net measures provided crucial support to all informal workers where they could be accessed particularly to widows and left by husband because they played the sole responsibilities towards their children and other family members (Srivastava, 2013). In the short term, they received emergency cash transfer from both the Union and State governments, various NGOs. Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (Rs. 500 per month) and state government schemes like Sneher Paras (One Time ex-gratia Payment of Rs. 1000), Prochesta (One time ex-gratia of Rs. 1000 exclusively for the pandemic situation of jobless persons) are very helpful as cash in hand. SasthaSathi (free medical facilities) of state level and Ujjala Yojona (free LPG connections to women for BPL Category) in central level are also two most beneficial schemes for these poor women. Even many people helped them as cash in hand to women workers. Many initiatives were taken by various organizations, NGOs, personal level to give them food relief, both in cooked and uncooked forms. The most important relief is the free ration which they avail till now from both the governments (Table 11).

Unconditional cash transfer as basic income is the immediate relief for the struggling families. It also helps to boost local economies as well. All social protection measures like food supply and cash transfer needed to be particularly focused on women informal workers. Although many women are less likely to know about all schemes that are beneficial for them and are less comfortable with digital modes to access the schemes, but gradually they are accustomed to take the benefits due to the initiatives taken by administration and knowing from relatives or neighbours.

Major findings

The above analysis portrays the struggle of urban women informal workers for their existence against this deadly situation. Women engaged particularly in informal sectors are surrounded by aggression of socio-cultural, economic and even political vulnerabilities. Their psychological, political and socio-economic well-being needs urgent attention along with labour rights. These women require the gender sensitive rights with welfare approach based on long-term goals. This becomes possible only when multiple stakeholders such as central to state administrations, NGOs, local communities and worker’s associations together will give efforts at their level best for their welfare.

Figure 9 clearly reveals the expectations of the women informal workers from government as the urgent basis. They also invariably mentioned that these are all ‘words of mouth’; nothing will happen in the future.

The Government of all levels should urgently identify the sectors where women workers are considered as the most vulnerable due to the complete absence of any protection and recognition as workers, such as domestic work or home-based petty manufacturing. Administration should immediately take action for their registration, social security, protection from exploitation and sexual harassment, and access to labour rights and laws and implementation of grievance redressal mechanisms.

This is the proper time for the revival of local and self-sufficient production and consumption networks as a more viable alternative to the massive supply chains. This is also the high-time for the implementation of the universal basic income which will eventually boost up the demand at the market by enhancing the purchasing power of the poor (Chakraborty & Emanuel, 2020).

Raising voices, trade unions, cooperatives are crucial need for these workers to be visible, build self-confidence and influence policies. The majority of urban women informal workers in study areas are not registered as workers. Therefore, they have more limited access to social and economic benefits of government schemes during this crisis period. The three major aspects of the informal economy—namely, the existence of casual labour force in greater number, para-legality, and lack of organization are put into question.

Many associations and organizations had already initiated to fight for justice to the workers of informal sectors considering the burning issues like equal pay for equal job, personal as well as social security and legal labour rights particularly during this pandemic situation (Roy, 2020). Both the Union and State Governments had already announced relief packages as stated earlier during lockdown and unlock periods to help the informal sector workers. Effective PDS and sanction of cash transfers as well as doubling food grain rations are helpful to a greater extent for the survival of these workers (Dreze, 2020). Besides all these, the troubles of the informal workers are still continued because the expenditure of non-food things cannot be met easily through these temporary aids.

The effective planning is necessary to boost up this slow economy. For this, a long term basis relief package should be sanctioned for the livelihood sustainability of these poor and marginalized women workers. Temporary relief to pay house rent and utility bills should be extended. The most important thing is that all these activities should be efficiently monitored by administrations, law enforcing agencies and NGOs so that the reliefs reach to the proper needy persons. The local administration should pay greater attention to look after the rehabilitation process of those informal shops which are constructed on the footpaths. This could help in both ways. First, the workforce of this sector will get rid from the threats of eradication and also will be able to give stability to their family. Second, people of both Midnapore and Kharagpur cities will be free from the hectic traffic congestion which they suffer on the daily basis.

Women have played a crucial role for local communities, particularly for their own community by extending help to supply food materials during COVID-19 pandemic (Sen & Atkins, 2020). The introduction of supportive economic packages, such as—cash in hand to the women, tax relief, extended unemployment opportunities, and extended family and child benefits will provide tangible help for the families of vulnerable women right now.

The loan at subsidized rate, relief in tax, stimulus funding and specific grants should be sanctioned to self-employed women in the informal sector.

Government should secure whatever possible it may be for encouraging women. Priority should be given to women dominating sectors. It is utmost necessary forbridging the gender pay gap by implementing proper laws and policies which will be helpful for proper evaluation of their works (ILO, 2020a, 2020b, 2020c; NCEUS, 2006; UNWOMEN, 2020).Above all, the Government should include representatives from this category of economic sector in decision making processes so, that, the ground truth will be revealed and recognized.

Strengthening women’s decision-making power, access to education, training, market-oriented skills development, access to technologies, access to digital literacy (Lakshmi Ratan et al., 2021), control of productive assets and financial inclusion are utmost necessities as medium term policy measures for capacity building of the female employees engaged in informal sectors.

Conclusion

The results revealed that, basically these urban informal workers were the poor and marginalized section of society. The COVID-19 pandemic induced lockdowns severely hit their livelihoods. Their education, income, savings and existing resources were not sufficient for coping with this situation. At the very first stage they were puzzled and disoriented, but gradually, they were habituated to cope with the damages. During unlock phases they again started their fight to move for the sustenance of families.

In this paper the main focus has given on the unparalleled struggle of urban women informal workers for their existence and calls for their prioritization in recovery packages. The impact of COVID-19 is more severe and long lasting on women’s employment due to social distancing, limited marketing timings, poor access of resources, the very little amount of savings, joblessness lack of copping capacity and insecurity. Women workers’ have experienced a lot of vulnerabilities in working places, family lives as well as in society, mainly due to their poverty and low social status.

They have got various types of help from government, non-government, community level and even individual level; but these are all in temporary basis. If governments of all levels do not pay specific attention to mitigate their necessities in permanent basis, they will just prepare the grave of risk to the loss of these vital economic contributors. This will again push them into a more critical and distressed future. Furthermore, if the economic empowerment of women starts to go in reverse mode then, their families, communities, and ultimately, societies will be in great danger. That is why; this risk is so severe, so crucial, and so deep rooted.

The COVID-19 pandemic condition has created a grave situation and what is petrifying is that anybody is not sure when the situation will normalize, until then everyone has to fight a lonely battle. This study witnessed an outstanding struggle of less educated and illiterate poor urban women informal workers who ought to be saluted.

Every critical situation gives an opportunity to learn and COVID-19 is actually no different. With the struggle against difficulties, survival in the vulnerable situation, no death due to hunger, this dark cloud also has a silver lining.

There is no guarantee that such types of situations will occur in the future but these women have learned so many things which they could not imagine earlier. They also realized the importance of measures such as technology in business (Joshi et al., 2020) which was ignored earlier.

One thing is clearly evidenced from the survey that at any cost they never lost their confidence and fought with teeth clenched to cope with this deadly pandemic situation. Till now they are fighting their own battle not only against this pandemic but also against the economy, society and culture.

References

Akkermans, J., Richardson, J., & Kraimer, M. L. (2020). The Covid-19 crisis as a career shock: Implications for careers and vocational behavior. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 119, 103434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103434

Banerjee, M., & Sharma, M. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 National lockdown on women waste workers in Delhi. Institute of Social Studies Trust. New Delhi, India. Retrieved August 16, 2021, from http://182.71.188.10:8080/jspui/bitstream/123456789/1266/1/1592391383_pub_ISST_-_Waste_Workers_Final_compressed.pdf

Berhanu, E. (2021). Street vending: means of livelihood for the urban poor and challenge for the city administration in Ethiopia. Journal of Public Administration, Finance and Law, 19, 101–120. https://doi.org/10.47743/jopafl-2021-19-09

Bertulfo, L. (2011). Women and the informal sector. Aus Aid Office of Development Effectiveness, Autralian Government.

Bonnet, F., Vanek, J., & Chen, M. (2019). Women and men in the informal economy: a statistical picture. Manchester: Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO).

Census of India. (2011). Retrieved from www.censusindia.gov.in

Chakraborty, L., & Emanuel, T. (2020). COVID-19 and macroeconomic uncertainty: Fiscal and monetary policy response. Economic & Political Weekly, 55(15).

Chakraborty, S. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 National lockdown on women informal workers in Delhi. Institute of Social Studies Trust. New Delhi, India. Retrieved August 18, 2021, from http://www.isstindia.org/publications/1591186006_pub_compressed_ISST_-_Final_Impact_of_Covid_19_Lockdown_on_Women_Informal_Workers_Delhi.pdf

Chant, S., & Pedwell, C. (2008). Women, gender and the informal economy: An assessment of ILO research and suggested ways forward. International Labour Office.

Chen, M. A. (2001). Women in the informal sector: A global picture, the global movement. SAIS Review, 21(1), 71–82.

Chen, M. A. (2016). The Informal Economy: Recent trends, future directions. New Solutions: A Journal of Environmental and Occupational Health Policy, 26(2), 155–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/1048291116652613

Christiane, H., Huskins, L., & Rollins, N. (2019). A descriptive study to explore working conditions and childcare practices among informal women workers in Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa: Identifying opportunities to support childcare for mothers in informal work. BMC Pediatrics, 19(382), 1–11.

Das, D. K., Choudhury, H., & Singh, J. (2015). Contract labour (regulation and abolition) act 1970 and labour market flexibility: An exploratory assessment of contract labour use in india’s formal manufacturing. (Working Paper Series; 300). Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations. Retrieved January 6, 2021, from http://icrier.org/pdf/Working_Paper_300.pdf

Delaney, A. (2020). Women in the informal world of work – experiences of lockdown under COVID-19 in India. Center for People, Organisation and Work, RMIT University. Retrieved January 3, 2021, from https://cpow.org.au/women-in-the-informal-world-of-work-experiences-of-lockdown-under-covid-19-inindia/

Dreze, J. (2020). View: The finance minister’s Covid-19 relief package is helpful, but there are gaping holes in it. The Economic Times (Mar. 28, 2020). Retrieved December 21, 2020, from https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/policy/view-the.

Gordon, R. H. (2000). Taxation of capital income vs. labour income: An overview. In S. Cnossen (Ed.), Taxing capital income in the European Union: Issues and options for reform (pp. 15–45). Oxford University Press.

Grown, C., & Sánchez-Páramo, C. (2020). The coronavirus is not gender-blind, nor should we be. World Bank Blogs, 20.

Hamilton, B. (2020). Informal sector in dire situation, yet contributes billions to economy. Lowvelder. Retrieved January 7, 2021, from https://lowvelder.co.za/619561/informal-sector-in-dire-situation-yetcontributes-billions-to-economy/

Hart, K. (1973). Informal income opportunities and urban employment in Ghana. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 11(1), 61–89.

International Labour Organisation (ILO). (2020a). Domestic workers and the COVID-19 pandemic understanding challenges ahead and evolving collective strategies. ILO Brief. Retrieved February 7, 2021, from https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—asia/—robangkok/—sronew_delhi/documents/meetingdocument/wcms_748030.pdf on 26th Dec 2020a.

International Labour Organisation (ILO). (2020b). Extending Social Protection to Informal Workers in the COVID-19 Crisis: Country Responses and Policy Considerations. Social Protection Spotlight, Geneva. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

International Labour Organisation (ILO). (2020c). COVID-19 crisis and the informal economy: Immediate responses and policy challenges. ILO Brief.

Jadhav, R. (2020). Why the Economic Devastation Caused by COVID-19 Will Hit Women Workers Harder? Hindu Businessline, 24 April, Retrieved March 18, 2021, from https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/news/why-the-economic-devastation-caused-by-covid-will-hit-womenworkers-hardest/article31421951.ece.%C2%A0

Jennings, J. E., & Brush, C. G. (2013). Research on women entrepreneurs: Challenges to (and from) the broader entrepreneurship literature? Academy of Management Annals, 7(1), 663–715.

Jennings, N. S. (1994). Small-scale mining: a labour and social perspective. In A. J. Ghose (Ed.), Small-scale mining: A global overview (pp. 11–18). A.A. Balkema.

Joshi, A., Bhaskar, P., & Gupta, P. K. (2020). Indian economy amid COVID-19 lockdown: A prespective. Journal of Pure and Applied Microbiology, 14 (suppl 1), 957–961. https://doi.org/10.22207/JPAM.14.SPL1.33

Kasseeah, H., & Tandrayen-Ragoobur, V. (2014). Women in the informal sector in Mauritius: A survival mode. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 33(8), 750–763. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-04-2013-0022

Kesar, S., Abraham, R., Lahoti, R., Nath, P., & Basole, A. (2020). Pandemic, informality, and vulnerability: Impact of COVID-19 on livelihoods in India. Canadian Journal of Development Studies/revue Canadienne D’études Du Développement, 42(1–2), 145–164. https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000428008

Kumar, B. R., Dudala, S. R., & Rao, A. R. (2013). Kuppuswamy’s socio-economic status scale–a revision of economic parameter for 2012. International Journal of Research and Devlopment of Health, 1(1), 2–4.

Kuppuswamy, B. (1976). Manual of socio-economic status scale (urban). Delhi: Manasayan.

Lahoti, R., Abraham, R., Kesar, S., Nath, P., & Basole, A. (2020). COVID-19 livelihoods survey. Azim Premji University. Retrieved March 19, 2021, from https://cse.azimpremjiuniversity.edu.in/wpcontent/uploads/2020/06/Compilation-of-findings-APU-COVID-19-Livelihoods-Survey_Final.pdf

Lakshmi Ratan, A., Roever, S., Jhabvala, R. & Sen, P. (2021). Evidence review of covid-19 and women’s informal employment: a call to support the most vulnerable first in the economic recovery. Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Magazine, A. (2020). Explained: In three new labour codes, what changes for workers and hirers? The Indian Express, Retrieved March 25, 2021, from https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/govts-new-versions-oflabour-codes-key-proposals-andconcerns-6603354

Mishra, D., & Singh, H. P. (2003). Kuppuswamy’s socioeconomic status scale–a revision. Indian Journal of Pediatrics, 70(3), 273–274.

Nanavaty, R. (2020). Pandemic and future of work: Rehabilitating informal workers livelihoods post pandemic. The Indian Journal of Labour Economics, 63 (suppl 1), 151–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-020-00271-0

NCEUS, (2006). Social security for unorganised workers. National Commission for Enterprises in the Unorganized Sector. Retrieved April 8, 2020, from http://dcmsme.gov.in/Social%20security%20report.pdf

NSSO. (2001a). Employment-Unemployment Situation in India 1999–2000, Round 55th, Report No. 458 – I and II (55/10/2), Ministry of Statistics and Program Implementation. Government of India, New Delhi.

OECD, D. (2020). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on jobs and incomes in G20 economies. ILO-OECD. Retrieved February 7, 2021, from https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/-cabinet/documents/publication/wcms_756331.pdf

Palinkas, L. A., Horwitz, S. M., Green, C. A., Wisdom, J. P., Duan, N., & Hoagwood, K. (2015). Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42(5), 533–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y

Palmer, R. (2007). Skills for work?: From skills development to decent livelihoods in Ghana’s rural informal economy. International Journal of Educational Development, 27(4), 397–420.

Pande, R., Schaner, S., Moore, C. T., & Stacy, E. (2020). A majority of India’s poor women may miss COVID-19 PMJDY cash transfers. Brief, Economic Growth Center, Yale University. Retrieved March 5, 2021, from https://egc.yale.edu/sites/default/files/COVID%20Brief.pdf

Patel, V. (2021). Gendered experiences of COVID-19: Women, labour, and informal sector. Economic and Political Weekly. 56(11).

Patton, M. Q. (2014). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice. Sage publications.

Roy, A. (2020). The attack on democratic, constitutional rights during the pandemic is ominous. The Wire. June 8, 2020. Retrieved March 18, 2021 from https://thewire.in/rights/covid-19-lockdown-indian-govt-rights-migrants-aruna-roy-interview

Saleem, S. M., & Jan, S. S. (2021). Modified Kuppuswamy socioeconomic scale updated for the year 2021. Indian Journal of Forensic Community Medicine, 8(1), 1–3.

Sapkal, R.S., Shandilya, D., Majumdar, K., Chakraborty, R., Roy, A. & Suresh, K.T. (2021). Workers in the time of COVID-19 Round II of the national study on informal workers, Action Aid Association, India. Retrieved March 30, 2021, from https://www.actionaidindia.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/WORKERSIN-THE-TIME-OF-COVID-19-I-Report-of-Round-2_Final-V2.pdf

Seibert, S. E., Kraimer, M. L., Holtom, B. C., & Pierotti, A. J. (2013). Even the best laid plans sometimes go askew: Career self-management processes, career shocks, and the decision to pursue graduate education. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(1), 169–182. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030882

Sen, P., & Atkins, K. (2020). The last mile model: exploring decentralised forms of governance by women community leaders. SEWA Bharat. https://sewabharatresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Last-Mile-Model-Decentralised-Governance-by-Women-Community-Leaders.pdf

Srivastava, R. (2013). A social protection floor for India. International Labour Office, ILO DWT for South Asia and ILO Country Office for India, New Delhi. Retrieved May 5, 2021, from https://www.ilo.org/newdelhi/whatwedo/publications/WCMS_223773/lang--en/index.htm.

Srivastava, R. (2020). Growing precarity, circular migration, and the lockdown in India. The Indian Journal of Labour Economics, 63(1), 79–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-020-00260-3

Sumalatha, B. S., Bhat, L. D., & Chitra, K. P. (2021). Impact of covid-19 on informal sector: A study of women domestic workers in India. The Indian Economic Journal, 69(3), 441–461.

The Fifteenth International Conference of Labour Statisticians. (1993). Resolution concerning statistics of employment in the informal sector. Retrieved October 5, 2021, from https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---stat/documents/normativeinstrument/wcms_087484.pdf

The Seventeenth International Conference of Labour Statisticians. (2003). Guidelines concerning a statistical definition of informal employment. Retrieved October 5, 2021, from https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---stat/documents/normativeinstrument/wcms_087622.pdf

U.N. (1993). System of National Accounts, United Nations.

United Nations. (2020). Sustainable Development Goals. Retrieved May 5, 2021, from https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/?menu=1300.

Vyas, M. (2020). Impact of lockdown on labour in India. The Indian Journal of Labour Economics, 63 (suppl 1), 73–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-020-00259-w

Williams, C. C., & Gurtoo, A. (2011). Women entrepreneurs in the Indian informal sector: Marginalisation dynamics or institutional rational choice? International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 3(1), 6–22. https://doi.org/10.1108/17566261111114953

Women, U.N. (2016). Women in informal economy. Retrieved May 5, 2021, from https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/in-focus/csw61/women-in-informal-economy.

Women, U.N. (2020). Domestic workers in Latin America and the Caribbean during the COVID-19 crisis. Policy Brief.

Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO). (2020a). Impact of public health measures on informal workers livelihoods and health. Retrieved May 5, 2021, from https://www.wiego.org/sites/default/files/resources/file/Impact_on_livelihoods_COVID-19_final_EN_1.pdf.

Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO). (2021). Challenges of organizing informal workers. Retrieved May 5, 2021, from https://www.wiego.org/challenges-organizing-informalworkers.

Yadav, A. (2020). India: Hunger and uncertainty under Delhi’s corona virus lockdown. Aljazeera. Retrieved June 11, 2021, from https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/4/19/india-hunger-and-uncertainty-under-delhis-coronavirus-lockdown

Zikic, J., & Richardson, J. (2007). Unlocking the careers of business professionals following job loss: Sensemaking and career exploration of older workers. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/revue Canadienne Des Sciences De L’administration, 24(1), 58–73.

Acknowledgements

We express our sincere thanks to the esteemed respondents who shared their valuable perceptions, experiences patiently with us during the hard time of COVID-19 pandemic situation. We are grateful to our beloved students who helped in field survey. We acknowledge those people, organizations and institutes, authors of various books and journals, and websites who have made their kind efforts to carry out this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both the authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by MM and CC. The first draft of the manuscript was written by MM and both the authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no potential conflict of interest with respect to this research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Ethical statement

It has been declare that this is an original piece of work by the authors. Manuscript has not submitted in any other journal for simultaneous consideration. The submitted manuscript is original and has not published elsewhere in any form of language. Other ethical responsibilities are truly maintained as per best of our knowledge.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mondal, M., Chakraborty, C. The analysis of unparalleled struggle for existence of urban women informal workers in West Bengal, India for survival and resilience to COVID-19 pandemic risk. GeoJournal 87 (Suppl 4), 607–630 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-022-10620-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-022-10620-9