Abstract

Upgrading logistic services in the context of international supply chains is not a smooth process. Upgrading may require the development of co-operative relationships, or alliances, involving large logistic service firms and their customers: multinational enterprises. Both sides may be unwilling and/or unable to engage in upgrading strategies in an alliance context. Fourth-party logistics is an example of a logistic product innovation entailing research-based advice as well as the design and implementation of new supply-chain solutions. It has the potential of stimulating spatial shift in global production networks and regional distribution systems (Visser and Lambooy, Geographisches Zeitschrift 92(heft 1+2):5–20, 2005). Using dynamic transaction-cost theory (Nooteboom, Learning and innovation in organisations and economies, 2000), this paper theoretically specifies and empirically measures three risks associated with the development of fourth-party logistics: dependence, unwanted spillovers, and conservatism. Case-study evidence reveals that dynamic transaction-cost theory partially explains the slow development of new logistic services in an alliance setting. Some aspects of conservatism are found to be relevant, along with risks of dependence due to specific investments in human resources and information systems. Other, not predicted but important factors, however, are the lack of credibility of service innovation by asset-based logistic firms, and strategic considerations of customers regarding logistic organization and control. The first factor implies that firms specializing in fourth-party services are likely to remain (very) limited in number. The second factor implies that this type of service provision is more likely to develop in dynamic port clusters, as customers prefer to tap into a variety of ideas from many different suppliers. In local clusters, interactions between firms can be relatively frequent, casual, short-lived and open, so that the structure of local networks is relatively decentralized, dense and flexible. This stimulates (logistic) innovation (Nooteboom, in Hanusch and Pyka (eds.) Elgar companion to neo Schumpeterian economics, 2006). In global supply chains, interactions between logistic service firms and their customers tend to have the opposite characteristics, which do not stimulate innovation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Logistics has become a key element in the competition strategies of multinational enterprises (MNEs). In a setting of enhanced logistic complexity resulting from globalization, these so-called ‘business owners’ concentrate on marketing, R&D, sales, and customer service functions, outsourcing the remaining activities to manufacturing and logistic firms. While MNEs increasingly face complex global logistic challenges (Christopher 1998; Hertz and Alfredsson 2003) while competing on the basis of logistic performance (delivery reliability, service differentiation, and so forth), they may not be fully willing to go so far to allow specialized logistic service providers resolve supply-chain optimization and integration problems (maximizing service at minimum costs). Similarly, such service provision does not develop automatically, despite the advantages of specialization, increasing demand for logistic research, advice, design, and implementation services, and decreasing profit margins in the logistics sector (Van Klink and Visser 2004).

This paper assumes that the above hurdles may be the result of certain risks associated with 4th party logistics (a function) by firms adding these value-added services to their portfolio and/or specializing in this direction. Fourth party logistics requires the development of alliances between usually large and internationally-operating logistic-service providers (LSPs) and their even larger, internationalized customers (MNEs). New information and communication technologies (ICTs) may contribute to alliance development, but the assumption in this paper is that residual uncertainties remain and that the associated transaction costs (Coase 1937; Williamson 1985) still have to be reduced. Other issues related to routines (Nelson and Winter 1982), path dependence (Boschma et al. 2002), dynamic capabilities (Zollo and Winter 2002), learning (Nooteboom 2000), and trust (Nooteboom 2002) may also play a role, and will be addressed in this paper.

The purpose of the study reported here was to use and test empirically the relevance of dynamic transaction-cost theory (Nooteboom 2000; Visser and Lambooy 2005) for analysing the development of 4th party logistics as an example of higher value-added services. We have followed three steps to achieve this purpose. The first is the description of the competitive impetus for 4th party logistic service provision. The second is the specification of a theoretical framework to detect factors hindering or triggering the development of this service type. The third is case-study research on the development of 4th party logistics in the setting of a reverse logistics operation.

The paper is structured as follows. Section “Defining 4th party logistics” describes and defines 4th party logistics as an example of value-added services and as a function that existing LSPs may add to their portfolio of services, or that other (new) firms may specialize in. Problems that may hinder 4th party logistic service development according to dynamic transaction-cost theory are specified in section “Problems hindering logistic service upgrading.” The research methodology is elucidated in section “Methodology.” Section “Evidence” reports the analysis of case study evidence. Our conclusions are presented in section “Discussion.”

Defining 4th party logistics

Over the last few decades, MNEs anxious to improve their global competitiveness have emphasized the supply chain as the principal area to improve competitiveness (Supply-Chain Council 2004).Footnote 1 Awareness is growing that it is not individual firms, but supply chains that compete with each other in selling products to final users (Bradley and Nolan 2000; Evans and Wurster 1997; Normann and Ramirez 2000; Rayport and Sviokla 1995). In addition, the total cost/service performance of a supply chain influences the purchasing decisions of final users. A chain, however, is as strong as its weakest link. Hence, supply-chain management (SCM) is critical. SCM aims at the integration of all the activities of all the firms in a chain in order to fulfil the demands of final customers more effectively and efficiently (Berglund et al. 1999; Ludema 2002). This integration often goes hand in hand with supply-chain reversal: using demand information upstream so that demand-pulled activities substitute for those that are supply pushed.

The emphasis on SCM may yield networked supply chains that are orchestrated by MNEs, and possibly also their LSPs. The expertise of LSPs can contribute to continuous improvements in the cost/service performance of supply chains, on the basis of product and process innovations, but also by suggesting new supply-chain configurations. Next, LSPs are involved in organizational innovations, since they move towards new positions in supply chains to generate higher added value for themselves (Panayides and So 2005; Carbone and Stone 2005). To be precise, 2nd party LSPs—subcontractors performing operational activities such as transport or warehousing for a customer (the 1st party), may transform into a 3rd and/or start fulfilling 4th party services and functions (see Table 1). It is important to note that the classification in 2nd, 3rd and 4th party services is about functions, not firms. An important issue in this paper is whether 4th party logistic functions may be developed by existing and asset-based firms (LSPs) adding these services to an existing portfolio of 2nd and/or 3rd party services, or that other firms, e.g. newcomers, may more easily move in this direction.

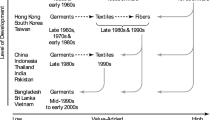

In the 1980s, logistic outsourcing led to the rise of 3rd party logistic service provision (Peper and Van Goor 2001), in the context of which supply-chain performance is optimized by centralizing and up-scaling operational tasks within the logistics firm, and/or by subcontracting these tasks to second-tier suppliers. In the former case, 3rd party LSPs and their clients may reap economies of scale and scope in logistic operations. In the latter case, 3rd party LSPs screen, select, contract, monitor and evaluate the performance of 2nd party firms, thus reducing transaction costs of outsourcing for the customer. In both situations, a 3rd party LSP ensures one-stop shopping for customers who retain the strategic control over the basic supply-chain concept used. In other words, they improve the operational effectiveness of chains, on the basis of first-order learning (Nooteboom 2000), but are not yet involved in strategic decisions concerning the basic logistic concept. In contrast, 4th party functions comprise undertaking research and advice on how to reconfigure supply chains spatially and functionally for improved supply-chain performance. Next, these functions include designing, developing, testing, implementing, and monitoring new supply-chain solutions. LSPs involving in these activities do so in a setting of strategic alliances with customers (‘co-shipperships’; De Wit and Van Gent 2001), where information sharing and joint problem solving may yield second-order learning. This induces the parties involved to propose and develop new logistic products and processes, i.e., logistic innovations.

As yet, there is hardly any empirical data available describing the extent to which 4th party logistics develops in different firms, countries or regions. However, there is reason enough for both MNEs facing complex global logistic challenges (Christopher 1998; Hertz and Alfredsson 2003) and LSPs suffering decreasing profit margins in competitive markets (Van Klink and Visser 2004) to add 4th party services to their portfolio or to specialize in this type of value-added functions. Nevertheless, existing LSPs seem to only slowly move in this direction (for evidence on the Dutch logistics industry, see Salden and Konrad 2005). This may be due to certain risks associated with upgrading services by existing LSPs in a setting of strategic alliances with customers. This paper concentrates on these risks and problems.

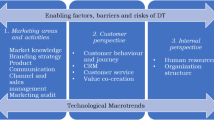

Problems hindering logistic service upgrading

This section features potential problems hindering the development of 4th party services. One may say that this development simply requires the implementation of new ICTs, but we hold another view. We use learning, innovation and transaction cost theory (Nooteboom 1992, 2000, 2006) to depict three problems that may affect the development of 4th party logistic functions and which may need to be resolved by mechanisms other than ICTs. The transaction cost concept (understood as the costs of transacting under uncertainty and managing the risks of dependence and spillover in inter-firm relationships) implies that the effect of reducing transaction costs by new ICTs is limited (Visser and Lambooy 2005). Below, we describe three central problems that MNEs and LSPs may encounter when developing value-added services such as 4th party logistics, and then derive a few hypotheses for empirical testing.

Dependence

According to transaction cost economics, specific investments induce a risk of dependence (relational risk), since these investments are lost in the event of opportunistic behaviour by the other party. A distinction may be drawn between these specificities: physical assets; human (or knowledge) assets; location (or site) assets; dedicated assets. Depending on the importance of suppliers (in terms of sales in absolute or relative figures), MNEs outsourcing logistics rely increasingly on LSPs, which may be perceived as risky in a situation where logistic cost/service performance is key in global competition and failure may cause a loss in market share. Conversely, however, LSPs make specific investments: in warehouses (physical assets); at a location required by customers (site specificity); software (dedicated assets); and/or training (human capital specificity). Hence, both parties may perceive a risk of dependence. The problem may deteriorate in the case of 4th party logistic service provision, since MNEs ask LSPs to develop novel solutions for complex logistic problems. Meeting this request requires both parties to invest time and money in knowledge exchange and make specific investments in a common language, mutual understanding, and trust (Nooteboom 2002).Footnote 2 The real problem with these dynamic transaction costs is the elapse of time between the perception of risk and investments at the start of a relationship, and future compensation in terms of yet uncertain supply-chain improvements (Visser and Lambooy 2005).

We may measure the risks of dependence from the viewpoint of the supplier or the buyer, distinguishing between gross and net dependence. Gross dependence refers to the one-sided dependence as perceived by one party on the other. Net dependence refers to the degree to which one party perceives itself to be more dependent on the other than vice versa.

Solutions to perceptions of risk of dependence fall into three categories: (a) balancing; (b) compensation; (c) eliminating causes of transaction costs.Footnote 3 Balancing refers to the point mentioned above that both parties are vulnerable to behavioural risks on the side of the other party. Compensation refers to safeguards (contracts, hostages). In the category of eliminating the causes of transaction costs, ICT may serve to reduce bounded rationality on the side of the buyer by disclosing the performance of supply chains and the role of various parties, including LSPs fulfilling 4th functions. This disclosure helps reduce the transaction costs of the buyer, but adds to the vulnerability and transaction costs on the suppliers’ side insofar as they are responsible for investing in specific software, hardware, and so forth. Trust is another helpful mechanism in eliminating the causes of risk. Trust is a predisposition to accept vulnerability in a context of opportunism and bounded rationality, expecting that a partner will not default but live up to more or less explicit expectations, agreements, norms and codes of conduct (see Nooteboom (2002) for an analysis and definition of trust; see Nooteboom (2006) for an analysis of the relation between trust and the transaction costs of learning and innovation in networks). A final mechanism in the category of eliminating the causes of transaction costs is that of dynamic capabilities. These reflect a capacity to foresee the future benefits of a logistic alliance (in terms of learning and innovation: new products, processes or chain configurations that reduce supply-chain costs and enhance service levels) and trade these benefits against perceived risk. So, dynamic capabilities entail the capacity to foresee and anticipate the future benefits of an innovation and balance them against current efforts, investment and costs effectively. Dynamic capabilities counteract bounded rationality and reduce opportunism as parties align short-term behaviour with long-term benefits. For operationalization purposes, we may take instances of knowledge exchange as proxies for dynamic capabilities, particularly in a setting of long-term projects that do not yield immediate benefits.

The above yields the following hypothesis for empirical research (H1): the problem of dependence will be especially relevant for MNEs enabling LSPs to fulfill 4th party functions, due to specific investments in transferring knowledge towards LSPs regarding the business of MNEs; vulnerability to logistic failure (implying serious loss of market share); and uncertain benefits in the form of future supply-chain improvements. The thus increasing net dependence of MNEs can not be fully compensated nor eliminated; hence, it will hinder the development of 4th party services by LSPs.

Unwanted loss of knowledge

Outsourcing also involves a risk of unwanted loss of knowledge (spillover risk). MNEs outsourcing logistic activities lose in-house logistic expertise, while the supplying LSPs accumulate the expertise required for the (specific) supply chains of the outsourcing party. This effect of experience (first-order learning) gives the LSP oligopolistic power, which is reinforced by internal economies of scale and scope in logistic operations. Risks of spillover also become evident, however, in the case of knowledge exchange between LSPs and MNEs working together to arrive at new solutions for complex global logistic problems. Such cooperation yields dynamic transaction costs related to anxiety about the potential leak of innovative logistic expertise to competitors.

The causes of spillover risk are fourfold: they relate to learning by interaction (relevant for both parties); competition (where suppliers also work for a buyer’s competitors, which is a threat to the latter); integration (where a buyer includes supplier expertise in its operations, insourcing instead of outsourcing, which is a risk for suppliers); competition between suppliers (where buyers may use various suppliers, urging them to adopt each other’s innovative or best practices). Hence, we may measure the risk of unwanted loss of knowledge from two viewpoints and in gross and net terms, so that four indicators of vulnerability obtain.

Solutions to spillover risks are in the same categories as those of dependence risks. Hence, balancing is possible, since both MNEs and LSPs are vulnerable. Compensation may be possible with the help of safeguards such as an extensive contract specifying the duration of a certain supply and its exclusive nature (an LSP may not use certain infrastructure in its work for competitors of the buyer, and so forth). In the case of logistics, compensation may thus prevent the use of multi-user infrastructure. In the category of eliminating causes, ICT is not likely to be of help. ICT tends to be specific, consisting of tailor-made software and other infrastructure, which may not be used for competitors for technical or contractual reasons. By its specificity, investing in ICT tends to augment the transaction costs for the investor, often the LSP. Trust is a helpful mechanism, however. In the case of spillover risks, trust in loyalty (intentional trust) is important for both parties, next to conditional trust and also informational trust (for both parties). Dynamic capabilities can also counteract the problem of spillover if parties opt for the long-term benefits of logistic partnerships instead of the short-term gains of opportunism.

The above yields the following hypothesis for empirical research (H2): the problem of spillover will increase for MNEs allowing an LSP to provide 4th party services, not so much due to learning by interaction (as that is relevant for both parties and thus constitutes a balanced problem) but especially competition—the LSP also works for the MNE’s competitors and may thus leak novel logistic know-how in undesirable directions. Hence, the risk of unwanted spillover will hinder the development of 4th services, especially in a setting of bilateral logistic alliances, involving two partners.

Conservatism

A general problem in supply chains that might also hinder 4th party service development is a lack of supply-chain awareness among the actors involved. This awareness should include an ability and/or willingness on the side of these actors to think in terms of the total costs of procuring, transforming, administering, transporting, and distributing products along the chain, along with an ability and/or willingness to consider the utility of co-operation within supply chains in terms of costs and service. Disregard of the collective roots of supply-chain excellence is thus the result of a combination of partiality (considering only some, not all costs) and self-centredness (considering oneself, not all concerned).

Past business and past linkage experience are two other causes of conservatism. On the side of MNEs, we may think of routines in procurement departments where personnel continue to focus on procurement prices, despite the fact that these only represent a fraction of total procurement and/or supply-chain costs (inability). Procurement managers may follow a divide-and-rule model and exercise the traditional buying power of the MNE, with a view to incentives rewarding such behaviour, whereas effective supply-chain management requires constructive relationships with suppliers. On the side of LSPs aspiring the provision of 4th party services, path dependence and routines may play a part, especially if these develop out of existing logistic service firms that have grown on the basis of traditional transport, warehousing, and forwarding activities. Well-proven and long-standing rules of business conduct seem attractive—in both good and bad times—compared with the uncertainties associated with such innovative services as 4th party logistics.

So, the causes of the problem of conservatism relate to partiality and self-centredness in the analysis of supply-chain costs and the benefits of supply-chain co-operation, to past business experience (routines), and to linkage experience (memory of key events in relation to other actors in the chain introducing feelings of pride, humiliation, respect, or hurt). Solutions may comprise ICT (insofar as it promotes supply-chain transparency, thus solving the problem of insufficient awareness while eroding vested interests); incentives for change-oriented behaviour (although these depend on the dynamic capabilities of top managers); trust in (a) the capabilities of the other party to understand the importance of SCM, logistic alliances, and system innovations, and the intentions of the other party to move in these directions, and in the conditions enabling actors to do so, and (b) dynamic capabilities. The latter should stimulate the intensity and quality of knowledge exchange to the extent that the parties involved can break through the walls of conservatism we refer to above (Nooteboom 1992; Visser 1996; Nooteboom 2000).

The above yields the following hypothesis for empirical research (H3): the problem of conservatism is a two-sided problem throwing a long shadow over the issue of 4th party services, as it negatively affects the perception of the future benefits of developing these services, and thus withholds both parties to embark on this road. The problem gets worse, however, in the case of existing asset-based LSPs, where path dependence and routines in the form of well-proven and long-standing rules of business conduct may significantly hinder innovative actors aiming at change that yet has to stand the prove of time and experience. In this case, MNEs may be even more suspicious about the benefits of 4th party service provision by specialist logistic firms.

Considering the above theoretical problems, new ICTs alone are not at all likely to serve as catalysts for 4th party services. Other variables related to dynamic transaction theory hinder this type of logistic innovation, and need to be addressed separately. The problems of dependence, unwanted spillover and conservatism are all expected to be significant in hindering 4th party logistic service development (hypotheses 1, 2 and 3). A task for empirical work is to verify whether or not these hypotheses hold, and in case they do, to assess the relative importance of the three problems.

Methodology

A research method is selected according to: (a) the nature of the research problem (with case studies appropriate for ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions and surveys for ‘who,’ ‘what,’ and ‘how much’ questions); (b) the degree of control over events (when high, experiments may be chosen; when low, case studies or surveys are appropriate); (c) the past or ongoing nature of events or processes (when processes are ongoing, case studies are most appropriate) (Yin 2003). In the present research context, these three criteria steer in the direction of case studies. The question of this paper is why 4th party logistics—a relatively new concept for which there may be demand from MNEs facing globalization and which may be attractive for LSPs facing lower profit margins—hardly develops, and how this can be explained.

Case studies serve not only exploratory and descriptive goals, but also explanatory purposes (Yin 2003). The design of a case study is closely related to the underlying theoretical framework. The researcher has to elaborate research questions, using alternative theories. In the setting of the current study, we used dynamic transaction costs theory to elaborate and specify research questions, a rival assumption being that new ICTs alone may enable the development of 4th party services (see the previous section).

Next, the unit of analysis has to be identified. Above, we have repeatedly stated that 4th party services develop in the context of supply chains and, more specifically, alliances between MNEs and LSPs. So, these alliances are the unit of analysis, in the setting of which we review the nature and extent of logistic service provision, the associated information exchange, and developments in this regard. However, the unit of analysis may differ from the sources of data, which may be so-called ‘embedded cases.’ In our case, we identified a specific operation in the context of an alliance between a LSP with one of its clients, where the target data was identified and collected through in-depth interviews.

The case study concerned was undertaken in 2006 on a reverse logistics operation (RLO) by a large, internationally operating LSP working for an even larger multinational customer in the computer industry. We held two or, when necessary, three structured interviews with in total four high-ranking managers who were primarily responsible for the RLO on both sides of the relationship; two persons in each company, occupying positions such as ‘director operations hi-tech logistics,’ ‘director operations spare-part logistics,’ and the like. When possible, the interviews were face-to-face; otherwise, they took place during telephone conversations. In the latter case, the questionnaire that served as a basis for the interview was sent by e-mail as an attached file for the respondent to read beforehand. In total, 51 questions were asked, covering the relevance of 4th party service development, the relevance of the three potential transaction-cost related problems in hindering this development, and the causes and solutions, including the use of new ICTs, for these problems (the questionnaire is available through ESM). The questions asked for a response in the form of a score on a 5-point Likert scale along with supplementary explanations. This qualitative information has been helpful in analysing the quantitative data. After concluding the RLO case study, we explored the validity of the results for other operations of the LSP for several customers. We did so during a face-to-face semi-structured interview and subsequent email communication with the director of the Product Development & Strategy department of the LSP.

The analysis of case-study data differs from the analysis of survey data. Case-study analysis is based on ‘pattern-matching,’ where the key question is the extent to which the data match up with the different propositions derived from rival theories (see the previous section). This logic of relating case-study data to theory is referred to as analytical or theoretical generalization. In statistical generalization, a case is merely part of a population, and statistical rules are used to relate these cases to that population, not with any theory concerning that population. In theoretical generalization, case-study results may be used to confirm, reject, amend or expand a certain theory (Ibid.). Critical case studies are used to collect and match data with rival theoretical propositions; the result of the matching process is the acceptance or rejection of the rival theories. The below case study fits this purpose. We used it to reject the rival hypothesis that new ICTs are sufficient to stimulate a product innovation such as 4th party logistic services, and to test the proposition that problems related with dynamic transaction-cost theory are relevant and explain the lack of development towards this type of services.Footnote 4

Evidence

In this section, we report the case-study evidence regarding the factors determining 4th party logistic service development. We first describe the case before presenting the evidence from two viewpoints: the LSP’s and the customer’s.

Background

In 1996, the customer firm signed a contract with a joint venture of two LSPs for the distribution of products to end users in nine European countries. A third LSP joined in later as a subcontractor. This firm was soon responsible for one third of the contract value. The customer asked the newcomer to develop a new, additional operation focused on reverse logistics in the Benelux and Iberian markets. This operation concerned return flows of small numbers of malfunctioning products, which are the result of customer service contracts. The operation grew by 400% in 2004, which is indicative of the importance of the reverse logistics market but also of the evolving relationship of the customer and the new LSP. Today, the two firms maintain a direct relationship, with the LSP perceiving the customer as “an innovative customer, with progressive ideas concerning logistics, outsourcing and partnerships” (oral communication of an LSP director, 25 June 2006). However, the relationship is also prone to “drawbacks and mixed feelings” (Ibid), which may be interesting in the light of the present study. Below, we consider the LSP’s views of the state of development of logistic services in the context of the RLO operation; we then turn to the customer’s views on these issues.

The LSP’s point of view

The LSP considers its relationship with the customer to be moving towards a partnership, where interactions take place to discover the relative strengths and weaknesses of different solutions proposed on both sides for one and the same problem, to analyse mistakes, to determine who can be entrusted with the role of problem solver, and so forth. Meetings are held to discuss the direction of the relationship. These often reinforce the position of the LSP as a logistic solution finder, in line with the critical assessments of the logistic initiatives of the customer. Trust is evolving slowly on the basis of experience, interaction, openness, and mutual respect.

The three problems that potentially hinder 4th party service development (dependence, vulnerability to spillover, and conservatism) are relevant, however. The two interviewed LSP managers originally thought that dependence was the principal, vulnerability the second, and conservatism the third most important of these. In the course of the interviewing process, however, it became clear that conservatism was a complex concept that had to be explained and understood well. Other arguments and considerations cropping up later shed new light on the nature of this problem, which eventually resulted in a higher ranking: first place. This reconsideration brought LSP’s perceptions in line with those of the customer (see Table 2).

Starting with the problem of dependence, the LSP mentions several factors: human asset specificity, investments in IT, knowledge exchange between the customer and LSP managers, the importance of the customer for the LSP (in terms of turnover) and vice versa (in terms of financial impact). Human asset specificity arises as a result of specific investments in expertise regarding reverse logistics. IT system development also requires initial specific investments in interface development and data entry, but the LSP devotes considerable effort into turning these specific systems into generic products that are marketable to other customers as well. Research is a key feature in this regard, since it contributes to the LSP’s understanding of what should be measured, how the performance of reverse logistic systems should be evaluated, and what activities can be standardized. This experience, knowledge, and the supporting IT can be included in other service offerings. Specific investments in human capital do not induce a high level of dependence of LSP, however. LSP’s net dependence on the customer is rated as ‘low.’ Solutions to the problem of dependence do not entail investing in IT, extensive contracts or incentive schemes, but do involve (in order of importance) intentional trust, informational trust, material trust, and competence trust (see Nooteboom (2002) for an explanation of these different aspects of trust). Dynamic capabilities are also important.

One issue with respect to unwanted spillovers is labour mobility. Consider, for example, an LSP engineer involved in the development of an advanced IT system who moves to a competitor, where he develops a similar system. This development would take about 1.5 years, however, owing to the embedded nature of the system, which only works on the basis of the LSP’s experience with return logistics, interface development, team work, and so forth. Another mechanism is a customer passing on a logistic novelty of an LSP to the firm’s competitors. Informal agreements not to do so are sufficient. Monitoring these agreements is easy, since the logistics service industry is a small world. Overall, the LSP does not consider itself to be vulnerable in gross terms, while the firm’s net vulnerability is almost negligible.

Regarding conservatism, both parties are considered to be ‘somewhat conservative.’ Reverse logistics may provide a relatively positive situation, however, since although this activity is challenging, it does not require substantial new investments in physical infrastructure. There is plenty of scope for creativity in bringing down transport and cross-docking costs. In other chains, past investments in storage and warehousing activities are important, enhancing the attention paid to fill rates by account managers on the LSP side. In these chains, procurement managers on the customer’s side have incentives (discounts on larger purchases) or have the power to impose sourcing decisions despite disagreements with marketing and service departments within the customer firm or with an LSP. So, stock levels and storage costs may increase more than they should from a logistic and marketing point of view. Finally, logistic services may be purchased on a cost basis, disregarding the quality and problem-solving skills of LSPs. In this case, conservatism leads to ‘penny-wise, pound-foolish’ outsourcing linkages that prevent relationships growing into effective logistic alliances.

So far, the evidence provided by the LSP leads us to confirm the three hypotheses specified in section “Problems hindering logistic service upgrading;” transaction-cost related problems are relevant and seemingly hinder the development of 4th party functions in the context of an alliance involving an existing LSP and its customer. The supplementary qualitative information provided by the two interviewees gives more information, however, confirming that customers are usually responsible for designing logistic chains, and that the LSP usually is not involved. When outsourcing logistics, customer requirements are quite standard. However, the LSP always considers whether the work a customer requests can be carried out straightforwardly or whether it can only be done if the LSP is allowed to improve the supply chain. This improvement requires research, advice, design, development, implementation and monitoring of alternative processes and products. So, work for a customer almost always consists of a bundle of simple outsourced tasks, after which the LSP starts launching proposals for more effective SCM. Customers expect logistic firms to develop these proposals without contractual requirements, however. As a result, 4th party logistic work is relevant but not paid for in an explicit manner.

To deal with this problem, the LSP often creates a budget for R&D activities in drawing up a contract. Next, its managers seek contact with students of (technical) universities to promote applied research linked to ongoing business, which bears insignificant costs. They also assign one or two recently-recruited employees with an academic degree to the team working on a contract, to promote interaction with older employees with different educational and professional backgrounds and undertake research with a view to optimizing supply-chain performance. On the whole, however, the LSP under review solves the problem of the lack of explicit budgets for 4th party services and expectations to develop activity in this direction by following two guidelines: (1) serve the customer’s wish to reduce supply-chain costs, including payments to the LSP; (2) pursue new supply-chain solutions as long as these do not ‘cannibalize’ current business. The first point implies investing in process efficiency so that cost savings exceed tariff and fee reductions, which generates a profit for the LSP. The second point means that the LSP may not want to move (at least not so fast) into the provision of 4th party services. New supply-chain concepts may work against short-term financial interests related to the deployment of existing assets, which cannot be compensated by the sale of advanced services such as 4th party logistics. This last problem in turn is the result of the credence good nature (cf. Visser and Lanzendorf 2004) of these services; a customer is unable to know before, during, and after consumption whether the service provided has been useful. To see this, we will turn to the point of view of the customer.

The customer’s point of view

Considering the activities of the LSP under review in the setting of various operations, the customer does not feel that the supplier is moving towards the role of 4th party service provision. According to one manager, “supply-chain design and optimization services generally spring from our own organization.” This in-house approach is the result of the specific logistic experience that customers have built up over a long time: expertise that is fully in line with specific product and market circumstances. If 4th party services develop, they would be within the customer’s organization or through a spin-off firm. On the whole, the customer prefers to carry out strategic logistic work in-house. The customer even provides the LSP under review with a reason for reinforcing the 2nd party profile, saying that subcontracting by LSPs reveals their weak internal cost structure. If a subcontractor of my LSP is cheaper than my LSP, “why would I not deal directly with that subcontractor?” This reasoning drives on 3rd party logistics based on internal scale and scope economies and geographical expansion, where the main difference from 2nd party services is the possibility of one-stop shopping that the 3rd party provider offers.

The customer nevertheless considers relationships with LSPs in terms of partnerships. As one manager put it: “our suppliers are partners owing to the increasing connectivity of firms: the need to adjust, fine-tune and connect IT systems, the time it takes to do so (many man-days, even years!), and the mutual understanding required before we can work together. Ask our suppliers, and they’ll say that we’re complex. A lot of understanding is needed about what we want, what is possible, how long it takes to change something, and so on” (oral communication, 12 July 2006). So, the interdependence of customers and LSPs is the result of specific investments in IT, human resources, and mutually-shared knowledge. The customer under review therefore prefers to work with existing suppliers and not to keep changing them. New firms trying to enter the supply network find doing so difficult. Their value proposition should be clear and related to design services or radically new solutions.

Turning to the three problems that may hinder 4th party logistic service development, the customer indicates that some aspects of conservatism are key features, with dependence ranking second and spillover the least important problem. To explain conservatism, the respondents point at the asset-based nature of LSPs: the resources they spend in physical assets, the need to safeguard the rate of return on these investments, and the resulting reduced credibility of advisory and design activities by the same firm. “They can only supply 4th party services after everything else has been taken care of.” Hence, the customer views the problem of conservatism as very relevant (score 5 on a Likert scale from 1 to 5, see also Table 2).

Regarding the problem of dependence, specific investments in IT and the understanding of each other’s business processes cause (inter) dependence, high switching costs, less competition, and fewer opportunities to “squeeze suppliers.” There is “no plug and play in logistics” owing to the need to adjust IT systems across the boundaries of the firms involved. There are so many connections and interfaces, and the systems are so complex, considerable experience and interaction are required to work together. This requirement is also the case for 2nd and 3rd party services, not only 4th party functions. According to the customer under review, replacing one supplier by another takes more than a year. In the meantime, logistic performance is the key to competition in global markets, so that switching implies a risk of reduced competitiveness and loss of market share. Customers thus also depend on LSPs. The converse is also true; LSPs also make specific investments (in warehouses, on belts, and so forth.), so that dependence is mutual and net dependence is moderate. LSPs are expected to make specific investments despite the absence of detailed written contracts specifying transaction volumes, contract duration, penalties, and so forth.

Regarding unwanted knowledge spillover, this risk may be present on both sides of the relationship, but it is not important. The LSP that loses an idea to its competitors via a customer does not see this as a problem, because of geographic complementarity. If the LSP works in the Benelux and the competitor is in Scandinavia, spillovers do not threaten the LSP’s short-term interests in the current market. Entry into new markets may be more difficult, but the LSP receives compensation, since customers “do not change suppliers like their underwear” in present markets. For customers, spillover risks are not very important. LSPs are professional enough not to reveal this type of spillover, or they agree on how to do it.

Analysis of the data reveals that there is a problem with the high ranking of conservatism in Table 2. In section “Problems hindering logistic service upgrading,” conservatism comprises elements of partiality and self-centredness regarding the analysis of supply-chain costs and the benefits of supply chain integration, along with elements of past business and past linkage experience. In the case study, the two parties argue that the physical asset-based nature of the work of LSPs hinders a transition towards 4th party logistics. For the LSP, the cannibalizing effect of the latter type of service is important, along with the problem that customers are unable to judge the value of these services and so they do not pay for them. As a result, the risk arises of losing 2nd and 3rd party businessFootnote 5 with insufficient compensation from the sale of new services. This financial argument has little to do with conservatism as defined in section “Problems hindering logistic service upgrading.” The three hypotheses are also confirmed on the basis of the customer’s point of view, but there seems to be something else going on.

From the customers’ viewpoint, the credibility problem also exists without sunk costs. The customer under review in the case study reasons as follows: for improved supply-chain performance, one needs advice, and certainly good advice, but most of all variety in advice. It is, therefore, interested in consulting logistic specialists, since it needs ideas and advice for effective SCM, but it has no interest in talking to only one firm (and certainly not one who has a clear interest in a certain type of advice). Instead, it wants to gather a number of contrasting ideas and viewpoints and use these as input in its own logistic centre performing other 4th party tasks: designing, developing, testing, implementing, and monitoring new supply-chain solutions. So, it wants to retain in-house absorptive capacity, in the first place, and it wants to gather, interpret, and analyse a variety of ideas and advices from various logistic specialists—LSPs able to provide 4th party inputs and ideas, in the second place. The quality of advices benefits from both variety and competition. Competition compensates for credibility problems that result from the ‘credence good’ nature of logistic advice and the asset-based work of LSPs. Variety stimulates innovation based on the possibility to compare ideas. So, rather than ‘conservatism’ on either side of the relationship, the brake on 4th party service development derives from a variety requirement that constrains specialization in 4th party service provision and that leads to insourcing instead of outsourcing of this function by customers. This variety requirement on the customer’s side goes beyond the three dynamic transaction-cost related problems used in this paper, thus putting the importance of the analytical framework and the three problems specified in section “Problems hindering logistic service upgrading” into perspective.

Validity

After concluding the case study on the RLO, we conducted a semi-structured interview with the director of the Product Development & Strategy Department of the LSP under review to assess the validity of the case-study results (see Table 2) for other operations of the LSP, for the customer under revies as well as other customers. The main result of this interview and later communication was that the ranking of problems would not change in the setting of these other operations. This stability is largely the result of the multi-user nature of large investments in physical infrastructure, such as warehouses, which reduces the specificity of these investments and the potential problem of one-sided dependence. Some customers may ask for a dedicated service, but in these cases, a 3–5-year contract compensates for the enhanced dependence of the LSP. The problem of dependence is, then, not ameliorated in a setting of operations requiring large investments in physical infrastructure.

Another matter came up at the interview, stressing the importance of the credibility issue. Customers requiring dedicated warehouses obtain exclusiveness at the expense of scope economies in handling and fixed costs. Simple price comparisons may stimulate the same customers to look for alternative suppliers after a contract expires. LSPs are aware of this risk of losing business, and respond by raising switching costs, mainly by making specific investments in IT and human resources, which have to be undertaken on both sides of the relationship. In this way, an LSP raises interdependence as a way of retaining customers. According to the interviewee, this defensive attitude is common among asset-based LSPs. In our view, it reinforces the credibility problem once these LSPs engage in 4th party services.

Discussion

This paper explores the relevance of dynamic transaction-cost theory for analysing the pace of development of a logistic system innovation: 4th party logistic service provision. Case-study evidence allows us to draw three sub conclusions: one on the relevance of two rival assumptions (regarding the role of IT and transaction costs); a second on the relative importance of three problems derived from dynamic transaction cost theory; the third concerns the possibility that other explanatory factors are at work. The first sub conclusion is that IT reinforces rather than diminishes problems associated with 4th party logistics. Therefore, to say that IT alone may stimulate 4th party logistic service development overlooks the complexity of the issues and risks at stake. A second sub conclusion is that the dynamic transaction-cost framework contributes to an explanation of the slow development of 4th party services, but only partially. The issue of conservatism ranks first, before the problems of dependence and spillover. A third sub conclusion is that other problems also hinder the rise of 4th party logistics. The physical asset-based nature of existing LSPs is particularly important in this regard. For buyers, this reduces the credibility of 4th party logistic advice; for suppliers, it is a financial disincentive to embark on this road. The credence-product nature of 4th party logistics is another issue that goes beyond the dynamic transaction cost framework. The greater the extent to which goods and services display features of credence products, the greater is the trust required for a transaction to take place and a relationship to change. There may be little trust in the usefulness of a service, so that explicit payment is also missing. To resolve this problem, aspirant 4th party LSPs should invest in a good track record and customer relationship upgrading, specialize in certain industries, disinvest in traditional activities, establish an independent subsidiary or stimulate spin-offs. Such a program would require a very high quality of strategic decision-making and dynamic capabilities on the part of LSPs, however, along with a high quality of change management to steer organizations of the size of a large LSP in this new direction. The question is whether such orientation and action on the LSPs’ part are enough, considering the strategic considerations on the customers’ part. The MNE in our study prefers to retain logistic expertise and strategic control within the firm, which is understandable given the features of global competition and the consequential importance of logistics. They want to retain their own absorptive capacity for strategic decision-making regarding new supply-chain designs, and require a number of logistic specialists to contribute to this. A more networked solution comprising different inputs from multiple specialists who may enter and leave the network appears to be preferable to a stable and closed bilateral partnership between specialist (the LSP) and customer (the MNE). Such a partnership allows customers to strike a balance between the beneficial effects of insourcing and outsourcing, and competition and cooperation.

To conclude: specialized 4th party service firms are likely to remain limited in number. Independent subsidiaries and spin-offs of existing logistic firms as well as industry entrants from other sectors (IT, software) have a better chance of developing 4th party services than existing and asset-based LSPs. Furthermore, value-added services like 4th party logistics may more easily develop in dynamic clusters, e.g. well-managed port areas, where customers may tap into a variety of logistic firms to develop new concepts. In clusters, interactions between firms are relatively frequent, casual, short-lived and open, so that the structure of inter-firm networks is relatively decentralized, dense and flexible. In supply chains, logistic alliances tend to centralize and involve LSPs and customers only, so that networks tend to be hierarchical, exclusive and well-structured, implying relatively rare, formal, repetitive and closed inter-firm interactions, which does not stimulate innovation.

Future research should test these two emerging hypotheses, i.e. that existing and asset-based LSPs are less likely to develop value-added services such as 4th party logistics than new entrants, spin-offs and independent subsidiaries, and that 4th party services are more likely to develop in (dynamic) clusters than elsewhere in a region lodging logistic activities.

Notes

This paper focuses on MNEs, as these are global players that increasing act like ‘business owners’ concentrating on the core competencies of marketing, R&D, sales, and customer service, outsourcing the remaining activities to both manufacturing and logistic firms. Hence, demand for 4th party logistic service functions is expected to be highest for this firm category.

Transaction costs are thus also important in a dynamic perspective. The traditional argument is that asset-specificity induces sunk and switching costs, creating lock-in in the relationship with the firm for which the investment was done. Nooteboom (Ibid.) argues that specificity is also related to “investments in crossing cognitive distance: in building appropriate absorptive capacity and capacity to make oneself understood by the partner”. This argument is based on a cognitive theory of learning, where learning is thought to take place on the basis of cognitive categories (rules of thought), which ‘condition knowledge in the double sense of enabling and limiting it’ (Nooteboom 2000, pp. 154–156).

The last solution is related to the foundations of TCE: opportunism; bounded rationality; specific investments; uncertainty; transaction frequency. See Visser and Lambooy (2005).

This is not easy. Nooteboom, however, observes that “variables such as asset specificity, transaction costs, innovation and trust are difficult to measure, [...] but [can be treated] as ‘latent ones’, which can be seen as being ‘spanned’ or ‘indicated’ by indicators that can be measured, often assessed by people on a five- or seven-point Likert scale. (...) The indicators can be combined into a joint variable, as an indirect measurement of the underlying latent variable” (2002, p. 156). Accordingly, we combined the indicators into a joint variable when drafting, testing, and revising a questionnaire for structured interviews.

Considering the doubts of customers concerning the added value of such services, the LSP even goes so far as to expand 3rd and 2nd party activities, thus showing customers they get ‘value for money’. Insourcing may thus be important in resolving a credibility problem.

References

Berglund, M., van Laarhoven, P., Sharman, G., & Wandel, S. (1999). Third party logistics: Is there a future? International Journal of Logistics Management, 10(1), 59–69.

Boschma, R. A., Frenken, K., & Lambooy, J. G. (2002). Evolutionaire economie: Een inleiding. Bussum: Coutinho.

Bradley, S. P., & Nolan, R. L. (2000). Sense and respond: Capturing value in the network era (1st ed.). Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Carbone, V., & Stone, M. A. (2005). Growth and relational strategies used by the European logistic service providers: Rationale and outcomes. Transportation Research E, 41, 495–510.

Christopher, M. (1998). Managing the global pipeline. Logistics and supply chain management (2nd ed.). Harlow: Pearson Education.

Coase, R. H. (1937). The nature of the firm. In O. E. Williamson & S. G. Winter (Eds.), The nature of the firm: Origins, evolutions and development (pp. 18–74). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

De Wit, J., & Van Gent, H. (2001) Economie en transport. Utrecht: Uitgeverij Lemma.

Evans, P. B., & Wurster, T. S. (1997). Strategy and the new economics of information. Harvard Business Review, 75(5), 71–82.

Hertz, S., & Alfredsson, M. (2003). Strategic development of third party logistics providers. Industrial Marketing Management, 32, 139–149.

Ludema, M. (2002). Designing a supply chain analysis framework. Paper presented at INCOSE 2002. Las Vegas, Nevada: International Council on Systems Engineering.

Nelson, R. R., & Winter, S. G., (1982). An evolutionary theory of economic change. Cambridge, MA and London: The Belknap Press.

Nooteboom, B. (1992). Towards a dynamic theory of transactions. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 2, 281–299.

Nooteboom, B. (2000). Learning and innovation in organisations and economies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nooteboom, B. (2002). Trust: Forms, foundations, functions, failures and figures. Cheltenham/Northhampton: Edgar Elgar Publishing.

Nooteboom, B. (2006). Transaction costs, innovation and learning. In H. Hanusch & A. Pyka (Eds.), Elgar companion to neo Schumpeterian economics. Cheltenham UK: Edward Elgar (Forthcoming).

Normann, R., & Ramirez, R. (2000). From value chain to value constellation: Designing interactive strategy. In S. P. Bradley & R. L. Nolan (Eds.), Sense and respond: Capturing value in the network era (pp. 185–220). Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Panayides, P. M., & So, M. (2005). Logistic service provider-client relationships. Transportation Research E, 41, 179–200.

Peper, H. J., & van Goor, A. R. (2001). Van kanaalleider naar ketenregisseur. Bedrijfskunde Special on Supply Chain Management, 73(1), 53–63.

Rayport, J. F., & Sviokla, J. J. (1995). Exploiting the virtual value chain. Harvard Business Review, 73(6), 75–85.

Salden, R., & Konrad, K. (2005). Fourth party logistics in the Netherlands. Utrecht: M.Sc. thesis, University of Utrecht.

Supply-Chain Council, Inc (2004) Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania USA http://www.supply-chain.org.

Van Klink, A., & Visser, E. J. (2004). Innovation in Dutch horticulture: Fresh ideas in fresh logistics. Journal of Economic and Social Geography, 95(3), 340–343.

Visser, E. J. (1996). Local sources of competitiveness: Spatial clustering and organisational dynamics in small-scale clothing in Lima, Peru. Amsterdam: Tinbergen Institute, PhD thesis.

Visser, E. J., & Lambooy, J. G. (2005). A dynamic transaction cost perspective on fourth party logistic service development. Geographisches Zeitschrift, 92(heft 1+2), 5–20.

Visser, E. J., & Lanzendorf, M. (2004). Mobility and accessibility effects of b2c e-commerce: A literature review. Journal of Social and Economic Geography, 95(2), 189–205.

Williamson, O. E. (1985). The economic institutions of capitalism. New York: The Free Press.

Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods (3rd ed.). London & New Delhi: Sage publications.

Zollo, M., & Winter, S. G. (2002). Deliberate learning and the evolution of dynamic capabilities. Organization Science, 13(3), 339–351.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Visser, EJ. Logistic innovation in global supply chains: an empirical test of dynamic transaction-cost theory. GeoJournal 70, 213–226 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-008-9133-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-008-9133-0