Abstract

A probabilistic approach that is based on Monte Carlo simulation (MCS) was developed in this study to design and perform sensitivity analysis of rock slope. The probabilistic approach uses MCS to perform a series of single objective optimizations for design of rock slope and to perform sensitivity analysis of rock slope stability. The MCS-based approach was used to evaluate the failure probability of a rock slope system and to determine a safe maximum slope height for rock slope design. To achieve this, the performance of different rock properties and rock slope conditions were explicitly considered towards achieving the target reliability index of the rock slope. The approach can achieve multiple rock slope design specifications using different target reliability indexes from a single run of MCS. The proposed probabilistic approach was illustrated through an example of rock slope design to determine feasible designs under different rock slope conditions. Also, sensitivity studies were performed to explore the effects of uncertainties in tension crack depth and water depth in tension crack, and variability in rock unit weight. The results show that the effects of uncertainties and variability on rock slope stability can be significant and should be incorporated during design analysis. Incorporating such uncertainties and variability in rock slope design is achieved with relative ease using the proposed approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

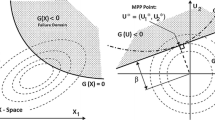

Over the past few decades, reliability analysis of slope stability has attracted significant research attention (Christian et al. 1994; Low 1997; Park and West 2001; Duzgun et al. 2003; Jimenez-Rodriguez et al. 2006; Hoek 2007; Low 2007; Li et al. 2009; Tang et al. 2013; Dadashzadeh et al. 2017; Aladejare and Wang 2018). Different past research works on reliability of rock slope have attempted to address one or more shortcomings of previous methods, ranging from treating rock parameters as random variables to incorporating correlation between shear strength parameters of rocks in reliability analysis of rock slopes (Low 2007; Li et al. 2009; Tang et al. 2013; Dadashzadeh et al. 2017; Aladejare and Wang 2018). Generally, the reliability of slope stability is frequently evaluated by a reliability index, β or slope probability of failure \(P_{f}\), which is defined as the probability that the minimum factor of safety (FS) is less than a reference value, say a unity for instance. Table 1 lists β and \(P_{f}\) for representative geotechnical components and systems with their expected performance levels. Geotechnical designs typically require a β value greater than 3.0 (i.e., \(P_{f}\) = 0.001) for an expected performance better than “Above average”. With the calculation of the slope probability of failure, the reliability analysis of the rock slope can be easily performed.

However, properties of rock are associated with uncertainties, some of which are unavoidable (Aladejare and Wang 2019a, b). Aladejare and Wang (2017a) reported that there is large range of variability in rock properties. The natural variability in rock properties is a direct result of various factors which rocks are subjected to during their formation. In geologic history of rocks, they are often affected by factors like properties of their parent materials, weathering and erosion processes, transportation agents, and conditions of sedimentation (Phoon and Kulhawy 1999; Wang and Aladejare 2015, 2016a). This natural variability cannot be reduced no matter our level of knowledge of rock properties and expertise displayed in estimating them (Baecher and Christian 2003). Added to this naturally occurring variability in rock properties are knowledge-based uncertainties, which include measurement errors, statistical uncertainty and transformation uncertainty (Phoon and Kulhawy 1999; Aladejare 2016, 2019). Unlike the natural variability, the knowledge-based uncertainties can be reduced if not eliminated. The magnitude of knowledge-based uncertainties reduces as level of knowledge increases (Baecher and Christian 2003).

Dealing with variability and uncertainties have been a major bottleneck to full adoption of probabilistic approaches in rock mechanics and rock engineering. To bypass the difficulty and often assumed complexity thrown up by uncertainties, conservative designs are generally adopted through the deterministic design approach. However, this deterministic approach does not consider uncertainties in an explicit manner, and experience shows that the conservative designs are not always invulnerable to failure (El-Ramly et al. 2002; Cao et al. 2016; Aladejare and Wang 2018). Some research works have shown that conservative design may either over estimate or underestimate failure probability of rock engineering systems (Wang and Aladejare 2016b; Aladejare and Wang 2017b).

Reliability-based design (RBD) approach has been developed and utilized to address the shortcomings of the deterministic approach (Baecher and Christian 2003; Fenton and Griffiths 2008; Peng et al. 2017; Aladejare and Wang 2018). Although, the RBD approach can consider uncertainties explicitly, an accurate statistical characterization of uncertainties of geotechnical parameters is necessary. However, rock properties contain variability and uncertainties and it may be difficult to establish the exact prevailing rock slope conditions at a rock slope site. Therefore, there is need to have an approach that can consider varying rock variabilities and uncertainties in rock slope conditions during design of rock slope and assessment of rock slope stability. Moreover, extensive study is yet to made on the sensitivity analysis of rock slope stability to varying rock properties and slope conditions through the incorporation of the variability and uncertainties affecting rock slope (e.g., Jimenez-Rodriguez and Sitar 2007; Li et al. 2011a, b; Basahel and Mitri 2019).

This paper develops an MCS-based probabilistic approach for design and sensitivity analysis of rock slope. The approach deals rationally with the variability and uncertainties in rock parameters and achieves the desired degrees of reliability with a single run of MCS. Furthermore, it provides a rational route to investigate the performance of the various rock slope geometries and conditions in current RBD towards achieving the desired reliabilities. The paper starts with a brief review on the deterministic design approach to rock slope using limit equilibrium model. Subsequently, an MCS-based probabilistic design approach is proposed, and its design steps are illustrated through a rock slope example that has been used in literature. The probabilistic design approach is used to perform sensitivity analysis of rock slope stability and offers the possibility of achieving designs for different reliability indexes. The approach is used to explore the effects of the uncertainties in tension crack depth and depth of water in tension crack, and variability in rock unit weight on feasible designs of the rock slope.

2 Deterministic Limit Equilibrium Design Model of Rock Slope

Consider a rock slope, which is assumed with a 1 m thick slice through the slope and has a water-filled tension crack (Hoek 2007). A two-dimensional limit equilibrium model with single failure model, in which the rock slope is assumed with a 1 m thick slice through the slope, which is shown in Fig. 1 is used in this study to perform reliability-based design of rock slope. The factor of safety (FS) is computed by resolving all forces acting on the slope into components that are parallel and normal to the sliding surface. The vector sum of the block weight acting on the plane is termed the driving force. The product of normal forces and the tangent of friction angle, plus the cohesion force, is the resisting force. The FS is calculated as the ratio of the sum of resisting forces to the sum of driving forces (Hoek and Bray 1981; Hoek 2007).

(Modified after Hoek 2007)

Illustration of a slope with water-filled tension crack.

The FS normally adopted depends on the purpose for which design is being made, either short or long-term use and magnitude of excavations for instance. Therefore, this study assumes that the slope is safe when the FS is greater than one (FS > 1), which is consistent with previous studies on reliability of rock slopes (Jimenez-Rodriguez et al. 2006; Johari and Lari 2016; Aladejare and Wang 2018). This study considers a situation of a rock slope with water-filled tension crack using the deterministic model, and its FS is computed as (Hoek 2007):

where c is the cohesive strength along sliding surface; A is the base area of wedge; W is the weight of rock wedge resting on the failure surface; \(\psi_{p}\) is the angle of failure surface; U is the uplift force due to water pressure on failure surface; V is the horizontal force due to the water in tension crack; \(\phi\) is the friction angle of sliding surface.

In Eq. (1), the area A, weight of rock wedge W, uplift force U, and force of water in tension crack V, are calculated as (Hoek 2007):

where H is the height of the overall slope, z is the depth of tension crack, \(z_{w}\) is depth of water in tension crack, and \(\psi_{f}\) is the overall slope angle measured from the horizontal. One of the design parameters for rock slope is the slope height, H and the maximum value of H that satisfies the FS requirement is usually required during rock slope designs. However, this cannot be explicitly or accurately evaluated from a deterministic perspective. In addition, the deterministic model [i.e., Eq. (1)] consist of some uncertain variables (i.e., slope parameters such as c and \(\phi\)) whose nature or characteristics cannot be fully explored in the deterministic design approach. It is therefore straightforward to extend the deterministic design to an MCS-based probabilistic design, where maximum value of H can be determined, and the uncertainty of the slope parameters can be incorporated.

3 MCS-Based Probabilistic Limit Equilibrium Design of Rock Slope

MCS is a numerical process of repeatedly calculating a mathematical or empirical operator in which the variables within the operator are random or contain uncertainty with prescribed probability distributions (Ang and Tang 2007; Aladejare and Wang 2017b). The numerical result from each repetition of the numerical process is considered as a sample of the true solution of the operator, analogous to an observed sample from a physical experiment. In the MCS-based probabilistic design, a design problem can be resolved using the probability distributions of site information available (e.g., rock shear strength parameters) and rock slope conditions. In the probabilistic design, the possible ranges of design parameters (e.g., slope height, bench height and width, etc.) are also specified. For a prescribed design scenario, MCS-based probabilistic design is used to calculate failure probabilities of different possible designs in this study and to determine the final design. In the design analysis, the design parameters are artificially viewed as independent discrete uniform random variables (Aladejare and Wang 2018).

Consider for instance, the probabilistic design of the rock slope illustrated in Sect. 2, where the mathematical operator involves computing FS [i.e., Equation (1)] and judgement of whether the slope is safe or not. Slope height (H) is one of the design parameters often required in mining engineering, especially during design of surface mining methods (Jimenez-Rodriguez et al. 2006; Aladejare and Wang 2018). Mining engineers and practitioners are interested in the determination of the feasible maximum H, which ensure safety of rock slope and achieves the target probability of failure \(P_{T}\) or target reliability index \(\beta_{T}\). A feasible maximum slope height, H ensures maximum excavation leading to greater return on investment of projects in mining operations. Note that slope angle is also an important design parameter in rock slope stability. However, this study focuses on a single design parameter (i.e., slope height, H) and it can be extended to cases where the determination of slope angle is more paramount in the rock slope design.

The rock slope design process starts with the calculation of the failure probabilities of the rock slope for a given value of H [i.e., conditional probability \(P(F|{\text{H}})\)] as (Aladejare and Wang 2018):

\(P({\text{H}}|F)\) in Eq. (6) is the conditional probability of H given that failure occurs, and it is defined as the ratio of the number of simulation samples where failure occurs for a specific value of H to the number of simulation samples where failure occurs; \(P(F)\) is the probability of occurrence of failure over total simulation samples, and it is defined as the ratio of the number of simulation samples where failure occurs to the total number of simulation samples; and \(P({\text{H}})\) is a constant, representing the inverse of the number of possible discrete values for H used in the design analysis. Note that Eq. (6) is incorporated in this study to be able to evaluate the probability of occurrence of failure and conditional probability of H, which change as the rock properties and slope conditions change.

Determination of feasible rock slope designs is performed by comparing the failure probability for specific value of H, \(P(F|H)\) with the target failure probability. In this case, the feasible rock slope designs are those with \(P(F|H) \le P_{T}\). Note that, the failure event F of a design parameter H is considered to occur when the performance of H is unsatisfactory according to a prescribed design criterion (e.g., its factor of safety is less than one). The maximum value of H for which \(P(F|H) \le P_{T}\) is the feasible maximum slope height, H which satisfy the FS requirement and achieves the target probability of failure \(P_{T}\) or target reliability index \(\beta_{T}\). Therefore, in addition to the other uncertain variables in the operator (i.e., rock properties and rock slope conditions), a probability distribution is artificially prescribed for the slope height (H).

Probability theory has been used to model the uncertainties in geotechnical materials by treating geotechnical parameters as random variables (Phoon and Kulhawy 1999; Aladejare 2016). Proper probability distribution functions can be used to model uncertainties that arise in geotechnical properties and parameters. For instance, normal or lognormal distributions are frequently used to model shear strength parameters of rock (i.e., c and \(\phi\)). To estimate the failure probability for different statistics using MCS-based design approach, the samples of the two main rock parameters, c and \(\phi\), are generated with the assumption that c and \(\phi\) are independent and normally distributed within typical ranges.

The slope height, H, which is a geometric dimension of the rock slope is rounded up to the nearest 1 m for construction convenience. Due to this, they are considered as discrete variables and treated as independent discrete random variables. To avoid bias in the occurrence of discrete values of H in the distribution space, H is treated as independent discrete random variable with a uniformly distributed probability mass function P(H). The uniform probability mass function P(H) is used to produce enough variation of H needed for calculating \(P(F|{\text{H}})\) and it does not reflect the uncertainty of H, which is a design parameter with no uncertainty associated with it.

4 Implementation Procedures

Figure 2 shows a flow chart for the implementation of the MCS-based probabilistic approach for design and sensitivity analysis of rock slope. The implementation procedure consists of six major steps and they are summarized as follows:

- 1.

Establish the deterministic computational model of rock slope for computing all the resisting and driving forces of rock slope, for the check of FS requirement.

- 2.

Model the uncertainties in rock parameters, rock slope conditions and obtain probability distribution of design parameter of interest (i.e., H).

- 3.

Perform MCS using random samples of uncertain variables and design parameter, H as inputs in the deterministic computational model.

- 4.

Perform statistical analysis of the simulation results to estimate \(P(F)\), \(P({\text{H}}|F)\) and \(P(F|{\text{H}})\).

- 5.

Determine feasible designs by comparing \(P(F|{\text{H}})\) with target failure probability \(P_{T}\) of interest. Subsequently, select the maximum H which satisfies the FS requirement and target failure probability as the final slope height, H.

- 6.

Repeat steps (4) and (5) for each design scenario under specific rock slope conditions or specifications to obtain its corresponding final design.

The approach presented in this study and its basic implementation steps are programmed in MATLAB and are illustrated using a rock slope design example in the next section. Note that the implementation of the proposed approach is simple and straightforward and can also be implemented using Microsoft Excel. This makes the adoption and adaptation of the proposed approach by mining engineers and practitioners to be easy, without major computational difficulty.

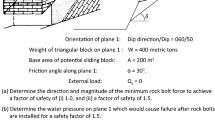

5 Illustrative Example: Sau Mau Ping Rock Slope

The case history of the Sau Mau Ping rock slope in Hong Kong is used in this paper to illustrate the MCS-based approach. Sau Mau Ping rock slope in Hong Kong has been the subject of several studies (Hoek 2007; Low 2007, 2008; Li et al. 2011a, b; Wang et al. 2013). Figure 1 shows an illustration of the geometry of the Sau Mau Ping rock slope for water-filled tension crack. Note that the rock mass of the Sau Mau Ping Slope is un-weathered granite and an initial study by Hoek (2007) led to its simplification as a single unstable block with a water-filled tension crack involving only a single failure mode. Adopting the slope parameters from Hoek (2007), potential failure plane is inclined at 35°, overall slope angle (i.e., \(\psi_{f}\)) is 50°, the unit weight of rock (i.e., \(\gamma_{r}\)) and water (i.e., \(\gamma_{w}\)) are 0.026 MN/m3 and 0.01 MN/m3, respectively, and they are all assumed to be fixed values.

Table 2 presents the random variables and their statistics for Sau Mau Ping rock slope by Hoek (2007). The random variables include shear strength parameters of the slope (c and \(\phi\)), depth of tension crack and depth of water in the tension crack. To better illustrate the idea of this study, only the shear strength parameters of the rock slope (i.e., c and \(\phi\)) are treated as random variable in this section. In the section named “Sensitivity analysis of rock slope stability”, the uncertainties in the depth of the tension crack and depth of water in the crack are considered to show how rock slope conditions affect reliability. To perform the reliability analysis, different slope heights, H (i.e., design parameter) are considered with H ranging from 20 m to 80 m with an increment of 5 m. The range of 20–80 m is considered appropriate as it captures the range or value of H used for similar reliability analysis in literature (Hoek 2007; Aladejare and Wang 2018).

The software package MATLAB (Mathworks 2018) is used in this paper to perform the MCS. The MCS starts with the generation of random samples for the design input parameter (i.e., H) and the uncertain variables (i.e., c and \(\phi\)) using their respective prescribed probability distributions and statistics as given in Table 2. This study adopts a sample size of 10,000,000 to further improve the resolution at small probability levels. Thus, a total of 10,000,000 random samples of H, c and \(\phi\) are generated, which leads to 10,000,000 calculations of FS. Therefore, 10,000,000 FS values are calculated using Eqs. (1–5) for each set of 10,000,000 random samples of H, c, and \(\phi\) together with other fixed parameters (i.e., \(\psi_{p} = 35^\circ\), \(\psi_{f} = 50^\circ\), \(\gamma_{w} = 0.01\;{\text{MPa}}\), \(\gamma_{r} = 0.026\;{\text{MPa}}\), z = 14 m and zw = 7 m). After the MCS, the number of MCS samples where failure occurs (i.e., FS < 1.0) at a specific value of H are counted. Then, conditional probability, \(P(F|{\text{H}})\) for failure (i.e., \(P_{f}\)) is computed accordingly using Eq. (6).

5.1 Determination of Feasible Designs

Figure 3 shows the numbers of failure and safe samples of slope height, H for different possible designs in the design space. The slope height, H is treated as discrete uniform random variable ranging from 20 m to 80 m with an increment of 5 m, yielding a total of 13 possible design values in the design space. A total of 10,000,000 random samples are simulated for the 13 possible design values of H. Based on the random samples, their corresponding values of performance function are evaluated using Eqs. (1–5), and failure samples corresponding to each design are then identified by determining whether their FS is less than unity (i.e., FS < 1.0). In Fig. 3, the peak of the histogram at around 769,230 shows the number of unconditional random samples of H simulated for each of the 13 possible designs. It also shows the number of failure and safe samples in the total simulated samples of H which are represented as red and blue columns in the histogram, respectively. The number of failure samples increases as H increases, which is logical since safety problems in mining increase as the height of excavation or slope height increases.

Figure 4 shows the conditional probability, \(P(F|{\text{H}})\) for failure (i.e., \(P_{f}\)) obtained from a single run of MCS and it is represented by open triangles at specific values of H. The solid line in Fig. 4 is used to depict the target failure probability, \(P_{T}\) which acts as the reliability constraint for the rock slope. The variation of the failure probability in the possible design space is helpful in making design decision between unsatisfactory and feasible designs in the design space. The target failure probability, \(P_{T}\) is taken as 0.00135 (i.e., target reliability index, \(\beta_{T} = 3.0\)). The feasible designs are the values of H that fall below the solid line (i.e., \(P_{T} = 0.00135\)) shown in Fig. 4. Although from Fig. 4, the values of \(P_{f}\) increases as H increases, the feasible designs for the rock slope are \({\text{H}} \le 4 5\;{\text{m}}\). Since the goal of every mining operation is to maximize profit while ensuring safety of the workers and workplace, the feasible design with a maximum H value (i.e., 45 m) is chosen as the final design of the rock slope. This will ensure safety and maximum excavation of the rock slope.

5.2 Feasible Designs for Rock Slope with Water Pressure in Tension Crack Only

In the previous subsection, the feasible designs for the rock slope are determined based on the assumption that the influence of ground water on the stability of the rock slope is due to the water present in both the tension crack and along the sliding surface. However, under some conditions, water pressure may develop in the tension crack only (Wyllie and Mah 2014, 2017; Wyllie 2018). For example, a scenario where a heavy rainstorm after a long dry spell results in surface water flowing directly into the tension crack and the remainder of the rock mass is relatively impermeable or the sliding surface contains a low-conductivity clay filling. In such scenario, the uplift force U could also be zero or nearly zero. In either case, the FS of the rock slope for these transient conditions is calculated by Eq. (1) with U = 0 and V given by Eq. (5) (Wyllie and Mah 2014, 2017; Wyllie 2018).

It is important that rock slope designs assess the sensitivity of the feasible designs to a range of realistic ground water pressure conditions and particularly the effects of transient pressures due to rapid recharge. Therefore, the MCS-based approach developed in this paper is also applied to this special condition of when water pressure develop in tension crack only. The results of the conditional probability, \(P(F|{\text{H}})\) for failure (i.e., \(P_{f}\)) for this condition are shown in Fig. 5. In Fig. 5, \(P(F|{\text{H}})\) at specific values of H are represented as open circles and the feasible designs for the rock slope is \({\text{H}} \le 5 0\;{\text{m}}\) when the target probability of failure is 0.00135. The feasible design with a maximum H value (i.e., 50 m) is chosen as the final design.

For comparison purpose, the \(P(F|{\text{H}})\) obtained from Sect. 5.1 (i.e., water present in both the tension crack and along the sliding surface) are also added to the figure as open triangles. Although, the open triangles and circles show similar progression pattern as the H values increases, the final design value when water is present in the tension crack only (i.e., \({\text{H = 50}}\;{\text{m}}\)) is greater than the value obtained in Sect. 5.1 (i.e., \({\text{H = 45}}\;{\text{m}}\)). This shows that the presence of water along the sliding face of a rock slope in the earlier case increases the possibility of slope failure more than when water is present in the tension crack only. Therefore, it is important that mining engineers and practitioners establish the absence or presence of water in both areas (i.e., tension crack and along the sliding surface) to explicitly determine an appropriate slope design. This is especially vital under transient conditions to avoid overestimation or underestimation of reliability of rock slope.

6 Sensitivity Analysis of Rock Slope Stability

To assess the influence of different rock slope conditions and uncertainties on reliability of slopes, sensitivity analysis is performed in this section. Firstly, the flexibility of the proposed approach to adjust to different target reliability indexes is explored. Then, the effect of uncertainties in depth of tension crack and the depth of water in the tension crack as well as variability of rock unit weight are also investigated.

6.1 Sensitivity on Target Failure Probability

Figure 6 shows the conditional probability, \(P(F|{\text{H}})\). for failure (i.e., \(P_{f}\)) and H for two different target failure probabilities. Figure 6 can be interpreted as results of a sensitivity on \(P_{f}\) or a reliability sensitivity study. Figure 6 shows feasible rock slope designs for the two cases in the illustrative example under different target failure probabilities. A new target failure probability, \(P_{T} = 0.000233\) (i.e., target reliability index, \(\beta_{T} = 3.5\)) is added to Fig. 5 to obtain Fig. 6, and the added target failure probability is represented with dashed lines. The new target reliability index probability (i.e., \(\beta_{T} = 3.5\)) depicts a performance level between “Above Average” and “Good” in Table 1 (e.g., Orr and Breysse 2008; Pan et al. 2017).

The feasible designs for the new \(P_{T}\) are those that fall below the dashed lines (i.e., \({\text{H}} \le 3 0\;{\text{m}}\) and \({\text{H}} \le 3 5\;{\text{m}}\) for water-filled slope and slope with water pressure in the tension crack only, respectively) and the final design is the maximum H among the feasible design values (i.e., H = 30 and 35 m, respectively). The proposed MCS-based approach allows feasible rock slope designs given different values of target probability of failure to be obtained directly from the MCS results without additional computation. It can be observed from Fig. 6 that the MCS-based approach allows design engineers to easily adjust \(P_{T}\) to accommodate the needs of design projects. This kind of adjustment can arise during design analysis, where mining engineers and practitioners need to adjust the design FS and reliability index to suit prevailing geo-mechanical conditions of rock slopes and economic requirement.

6.2 Effect of Uncertainty in Depth of Tension Crack

In practical design of rock slope, it may be difficult to accurately measure the depth of tension crack in a rock slope, especially in an undulating terrain where accessibility is limited. While it is easier to take a deterministic value for depth of such tension crack, uncertainty in the depth of tension cracks may have significant effects on rock slope designs. To explore the effect of uncertainty in depth of tension crack, a sensitivity study is performed in this subsection that considers the uncertainty in the depth of tension crack in the design. The proposed MCS-based probabilistic approach allows rock design engineers to easily incorporate the uncertainties.

For this sensitivity study, four cases of depth of tension crack, z, are considered. One case is when z is deterministic at 14 m, which was already used in Sect. 5. Two additional deterministic cases are included at situations where the depth of the tension crack is equal to the minimum and maximum values of slope height considered in the rock slope design (i.e., z = 20 m and 80 m). The fourth case of z considered is taken from Table 2, with z normally distributed with a mean of 14 m and standard deviation of 3 m. Therefore, MCS is performed using the two deterministic depths of tension crack of 20 m and 80 m, and a random depth of tension crack.

Figure 7 shows the results from the sensitivity studies in a plot of \(P_{f}\) against H. When the depth of tension crack is deterministic and increases from 14 to 80 m, the \(P_{f}\) against H relationship moves up of the plot. The \(P_{f}\). values at the same H values increases significantly as the depth of tension crack increases from 14 to 80 m. When the depth of tension crack is modelled as a random variable normally distributed with a mean of 14 m and standard deviation of 3 m, the \(P_{f}\) against H relationship almost overlaps with \(P_{f}\) against H relationship obtained when z is deterministic at z = 14 m. The similarities in the results of the two cases seems to suggest that the standard deviation of about 3 m in the depth of tension crack has little or no effect on the overall response of the rock slope. At z = 80 m, there is no feasible design, while the final designs at z = 14 m and 20 m are H = 45 m and H = 40 m, respectively. Also, the final design when z is randomly distributed with a mean of 14 m and standard deviation of 3 m is H = 45 m. This further suggests that there are close similarities in the results when z is considered deterministic at z = 14 m and when it is modelled as randomly distributed with a mean of 14 m and standard deviation of 3 m.

6.3 Effect of Uncertainty in Depth of Water in Tension Crack

Hoek (2007) assumed the mean depth of water to be a half of the depth of tension crack. He furthered that the maximum depth of water cannot exceed the depth of tension crack z and, this value would occur very rarely. Therefore, there is possibility that the depth of water in the tension crack could range between two extreme conditions, one is the tension crack not having water at all (i.e., zw = 0 m) and the other is the tension crack fully filled with water (i.e., zw = 14 m). The depth of water in tension crack could have significant effect on FS calculations and the final design. To explore the effect of depth of water in tension crack, a series of sensitivity studies with three different zw (i.e. zw = 0 m, 7 m and 14 m) was carried out. In addition, the zw is explicitly modelled as uncertain in the MCS, and it was considered as a random variable exponentially distributed between [0 m, 14 m]. The zw range is consistent with the two extreme conditions of zw suggested by Hoek (2007).

Figure 8 plots the results of \(P_{f}\) against H from the sensitivity studies. When zw is deterministic and increases from 0 m to 14 m, the \(P_{f}\) values increase for every H and cause upward movement of the \(P_{f}\) against H relationship of the plot. The \(P_{f}\) values at the same H values increases significantly as the water depth in tension crack increases from 0 to 14 m. When the water depth in tension crack was modelled as a random variable distributed between [0 m, 14 m], the \(P_{f}\) against H relationship almost overlaps with \(P_{f}\) against H relationship obtained when zw is deterministic at zw = 7 m. This suggests that a deterministic value of 7 m seems to be equivalent to modelling the zw as a random variable distributed between [0 m, 14 m]. At zw = 0 m, 7 m and 14 m, the final designs are H = 50 m, 45 m and H = 40 m, respectively. Also, the final design when zw is exponentially distributed between [0 m, 14 m] is H = 45 m. This further suggests that there are close similarities in the results when zw is considered deterministic at zw = 7 m and when it is modelled as exponentially distributed between [0 m, 14 m]. However, the significantly different final designs at zw = 0 m and 14 m (i.e., H = 50 m and H = 40 m, respectively) underscores the importance of establishing the absence or presence of water or a tension crack fully filled with water in the design of rock slopes.

6.4 Effect of Variability in Unit Weight of Rock

It is generally assumed that the variability in rock unit weight is small, with a coefficient of variation (COV) of less than 10% (Aladejare and Wang 2017a). Therefore, rock unit weight has frequently been considered as deterministic in reliability analyses (Hoek 2007; Aladejare and Wang 2018). Although the variability of rock unit weight is relatively small, its effect on the design might not be necessarily negligible, particularly for the design of rock slope that is expected to have a long-life span. To quantify the effect of variability in rock unit weight, a sensitivity study is performed in this section that models \(\gamma_{r}\) explicitly as a normally distributed random variable with mean 2.6 tonnes/m3 and five different values of COV of \(\gamma_{r}\) (i.e., \(COV_{{\gamma_{r} }}\) = 5%, 10%, 15%, 20% and 30%).

Figure 9 shows the results of \(P_{f}\) against H relationships when \(\gamma_{r}\) is considered uncertain at different COVs. As shown in Fig. 9, the final designs for the rock slope when COV of \(\gamma_{r}\) is taken as 5% (i.e., open rhombuses), 10% (i.e., open circles) and 15% (i.e., open squares) are determined as H = 45 m. However, the feasible designs when COV of \(\gamma_{r}\) is taken as 20% (i.e., open triangles) and 30% (asterisks) are determined as H = 40 m and 35 m, respectively. This result shows that the effect of \(\gamma_{r}\) variability on rock slope designs is minimal at COV of between 5 and 15% while it becomes more significant at COV of 20% and 30%. From the results of the analysis, it is evident that while the unit weight can be considered and taken deterministic in some designs, especially if the COV of \(\gamma_{r}\) is not more than 15%, doing same at a COV more than 15% can have significant effect on the design. At a COV of more than 15%, the unit weight should be modelled as a random variable to fully depict its variability. The MCS-based probabilistic approach proposed in this study provides a straightforward and rational vehicle for proper consideration and integration of such variability into reliability analysis of rock slopes with relative ease.

7 Summary and Conclusions

This study proposed an MCS-based probabilistic approach for design and sensitivity analysis of rock slope. The proposed approach analyses responses of rock slope under varying conditions of rock slope and determines the feasible designs by comparing the analysis results with a target reliability index or failure probability. Statistical analysis was carried out to construct histogram for failure and safe samples of slope height from the MCS results. The failure probability was estimated from the failure samples of rock slope height, and feasible designs were determined by comparing the failure probability of slope height with the target failure probability. Because one of the key objectives of mining engineering operation is to maximize profit while ensuring safe working condition, the feasible design with a maximum value of rock slope height is taken as the final design in the proposed approach. This will ensure maximum excavation of rock slope, and greater return on investment of mining projects.

In the approach, MCS was used as a numerical process for repeated calculations of the factor of safety in a bid to evaluate the failure probability of the rock slope system. A unique feature of the proposed approach is that the different variabilities and uncertainties of rock properties and rock slope conditions are explicitly considered and incorporated into the sensitivity analysis. The approach allows the same set of samples simulated from a single run of MCS to be used through the values of their failure probability for different reliability indexes of the rock slope. Using the proposed approach, the variation in the failure probability corresponding to different possible values of rock slope design parameters can easily be evaluated using MCS. One additional benefit of the proposed approach is that it reduces the complexities often associated with reliability analysis by using a series of single-objective optimizations to achieve sensitivity analysis of rock slope stability. Thus, the proposed approach can be implemented in a rather efficient and straightforward manner, without requiring complex computational skill and time.

The proposed MCS-based probabilistic approach has been illustrated with an example of rock slope design. The results show that the proposed approach is effective in incorporating the variability and uncertainties in rock properties and slope conditions in the design and analysis of mining and geotechnical systems. The results of the illustrative rock slope design example show that the design value of the slope height fall within the typical slope height ranges reported in literature for the adopted rock slope site. The probabilistic approach is flexible and can adjust to different reliability constraint during design analysis. Using the same failure samples of slope height, final designs at different reliability indexes can be obtained without additional computational effort. The proposed approach explores the effects of uncertainties in depth of tension crack and water depth in tension crack depth and variability in rock unit weight. The uncertainties in depth of tension crack and water depth in tension crack are shown to have effects on the design of rock slope height, especially at extreme slope height and water conditions. It is also found that, although the rock unit weight variability is relatively minor, it has significant effect on the design of rock slope, especially when the COV is beyond around 15%.

References

Aladejare AE (2016) Development of Bayesian probabilistic approaches for rock property characterization. Ph.D. thesis, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Aladejare AE (2019) Evaluation of empirical estimation of uniaxial compressive strength of rock from measurements of index and physical tests. J Rock Mech Geotech Eng (Accepted)

Aladejare AE, Wang Y (2017a) Evaluation of rock property variability. Georisk: Assessment and Management of Risk for Engineered Systems and Geohazards 11 (1): 22-41

Aladejare AE, Wang Y (2017b) Sources of uncertainty in site characterization and their impact on geotechnical reliability-based design. ASCE-ASME J Risk Uncertain Eng Syst Part A Civ Eng 3(4):04017024

Aladejare AE, Wang Y (2018) Influence of rock property correlation on reliability analysis: from property characterization to reliability analysis. Geosci Front 9(6):1639–1648

Aladejare AE, Wang Y (2019a) Probabilistic characterization of Hoek–Brown constant mi of rock using Hoek’s guideline chart, regression model and uniaxial compression test. Geotech Geol Eng 1–16

Aladejare AE, Wang Y (2019b) Estimation of rock mass deformation modulus using indirect information from multiple sources. Tunn Undergr Space Technol 85:76–83

Ang AH-S, Tang WH (2007) Probability concepts in engineering: emphasis on applications to civil and environmental engineering. Wiley, New York

Baecher GB, Christian JT (2003) Reliability and statistics in geotechnical engineering. Wiley, Hoboken, p 605p

Basahel H, Mitri H (2019) Probabilistic assessment of rock slopes stability using the response surface approach–a case study. Int J Min Sci Technol 29(3):357–370

Cao Z, Wang Y, Li DQ (2016) Quantification of prior knowledge in geotechnical site characterization. Eng Geol 203:107–116

Christian JT, Ladd CC, Baecher GB (1994) Reliability applied to slope stability analysis. J Geotech Eng 120(12):2180–2207

Dadashzadeh N, Duzgun HSB, Yesiloglu-Gultekin N (2017) Reliability-based stability analysis of rock slopes using numerical analysis and response surface method. Rock Mech Rock Eng 50(8):2119–2133

Duzgun HSB, Yucemen MS, Karpuz C (2003) A methodology for reliability-based design of rock slopes. Rock Mech Rock Eng 36(2):95–120

El-Ramly H, Morgenstern NR, Cruden DM (2002) Probabilistic slope stability analysis for practice. Can Geotech J 39(3):665–683

Fenton GA, Griffiths DV (2008) Risk assessment in geotechnical engineering. Wiley, New York

Hoek E (2007) Practical rock engineering. Institution of Mining and Metallurgy, London, p 325p

Hoek E, Bray J (1981) Rock slope engineering, 3rd edn. Institution of Mining and Metallurgy, London

Jimenez-Rodriguez R, Sitar N (2007) Rock wedge stability analysis using system reliability methods. Rock Mech Rock Eng 40(4):419–427

Jimenez-Rodriguez R, Sitar N, Chacon J (2006) System reliability approach to rock slope stability. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 43(6):847–859

Johari A, Lari AM (2016) System reliability analysis of rock wedge stability considering correlated failure modes using sequential compounding method. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 82:61–70

Li DQ, Zhou C, Lu W, Jiang Q (2009) A system reliability approach for evaluating stability of rock wedges with correlated failure modes. Comput Geotech 36(8):1298–1307

Li DQ, Jiang SH, Chen YF, Zhou CB (2011a) System reliability analysis of rock slope stability involving correlated failure modes. KSCE J Civ Eng 15(8):1349–1359

Li DQ, Chen YF, Lu WB, Zhou CB (2011b) Stochastic response surface method for reliability analysis of rock slopes involving correlated non-normal variables. Comput Geotech 38(1):58–68

Low BK (1997) Reliability analysis of rock wedges. J Geotech Geoenviron Eng 123(6):498–505

Low BK (2007) Reliability analysis of rock slopes involving correlated non-normals. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 44(6):922–935

Low BK (2008) Efficient probabilistic algorithm illustrated for a rock slope. Rock Mech Rock Eng 41(5):715–734

Mathworks (2018) MATLAB—the language of technical computing. http://www.mathworks.com/products/matlab/

Orr TL, Breysse D (2008) Eurocode 7 and reliability-based design. In: Phoon KK (ed) Reliability-based design in geotechnical engineering: computations and applications, ch. 8, pp

Pan Q, Jiang YJ, Dias D (2017) Probabilistic stability analysis of a three-dimensional rock slope characterized by the Hoek–Brown failure criterion. J Comput Civ Eng 31(5):04017046

Park HJ, West TR (2001) Development of a probabilistic approach for rock wedge failure. Eng Geol 59(3–4):233–251

Peng X, Li DQ, Cao ZJ, Gong W, Juang CH (2017) Reliability-based robust geotechnical design using Monte Carlo Simulation. Bull Eng Geol Environ 76(3):1217–1227

Phoon KK, Kulhawy FH (1999) Characterization of geotechnical variability. Can Geotech J 36(4):612–624

Tang XS, Li DQ, Rong G, Phoon KK, Zhou CB (2013) Impact of copula selection on geotechnical reliability under incomplete probability information. Comput Geotech 49:264–278

US Army Corps of Engineers (1997) Engineering and design: introduction to probability and reliability methods for use in geotechnical engineering. Engineer Technical Letter 1110-2-547. Washington, DC: Department of the Army

Wang Y, Aladejare AE (2015) Selection of site-specific regression model for characterization of uniaxial compressive strength of rock. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 75:73–81

Wang Y, Aladejare AE (2016a) Bayesian characterization of correlation between uniaxial compressive strength and Young’s modulus of rock. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 85:10–19

Wang Y, Aladejare AE (2016b) Evaluating variability and uncertainty of geological strength index at a specific site. Rock Mech Rock Eng 49(9):3559–3573

Wang L, Hwang JH, Juang CH, Atamturktur S (2013) Reliability based design of rock slopes—a new perspective on design robustness. Eng Geol 154:56–63

Wyllie DC (2018) Rock slope engineering: civil applications, 5th edn. CRC Press, Boca Raton

Wyllie DC, Mah C (2014) Rock slope engineering. CRC Press, Boca Raton

Wyllie DC, Mah CW (2017) Movement monitoring. In Rock slope engineering (pp 320–333). CRC Press, Boca Raton

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by University of Oulu including Oulu University Hospital.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Aladejare, A.E., Akeju, V.O. Design and Sensitivity Analysis of Rock Slope Using Monte Carlo Simulation. Geotech Geol Eng 38, 573–585 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10706-019-01048-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10706-019-01048-z