Abstract

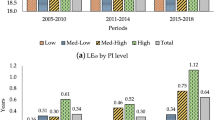

The aim of this paper is to examine differences in life expectancy (LE) between self-employed (SE) and paid employee (PE) workers when they become retirement pensioners, looking at levels of pension income using administrative data from Spanish social security records. We draw on the Continuous Sample of Working Lives (CSWL) to quantify changes in total life expectancy at age 65 (LE65) among retired men over the longest possible period covered by this data source: 2005–2018. These changes are broken down by pension regime and initial pension income level for three periods. The literature presents mixed evidence, even for the same country–for Japan and Italy, for example–with some studies pointing to higher life expectancy for SE than for PE retirement pensioners while others argue the opposite. In Spain, LE65 is slightly higher for the SE than for PE workers when retirement pensioners. For 2005–2010, a gap in life expectancy of 0.23 years between SE and PE retirement pensioners is observed. This widens to 0.55 years for 2014–2018. A similar trend can be seen if pension income groups are considered. For 2005–2010, the gap in LE65 between pensioners in the lowest and highest income groups is 1.20 years. This widens over time and reaches 1.51 years for 2014–2018. Although these differences are relatively small, they are statistically significant. According to our research, the implications for policy on social security are evident: differences in life expectancy by socioeconomic status and pension regime should be taken into account for a variety of issues involving social security schemes. These include establishing the age of eligibility for retirement pensions and early access to benefits, computing the annuity factors used to determine initial retirement benefits and valuing the liabilities taken on for retirement pensioners.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Researchers can request versions of the CSWL by post. A separate request must be made for each version. Requests consist of a user profile describing the project being carried out and a document accepting the CSWL’s conditions of use. These are available at the following address: http://www.seg-social.es/wps/portal/wss/internet/EstadisticasPresupuestosEstudios/Estadisticas/EST211

Notes

Also referred to by several authors as the Continuous Working Life Sample (CWLS) or the Continuous Survey of Working Lives (CSWL).

It should be stressed that ethics approval is not required for this data set, since its use for scientific purposes has been regulated since its creation. Researchers can request versions of the CSWL by post, although a separate request has to be made for each version. Requests consist of a user profile describing the project being carried out and a document accepting the CSWL’s conditions of use.

The sustainability factor, which was supposed to apply from January 2019 to adjust initial pensions on the basis of changes in life expectancy, was also suspended until 2023. A commission will determine how to proceed with both the sustainability factor beyond 2023 and the new indexation mechanism.

The general system accounts for 71,5% of pensions and 76% of contributors (March 2020), Seguridad Social (2020b).

Until 31 December 2012 the statutory retirement age was 65. From 2027 onwards there will be two standard retirement ages: 65 with 38.5 years' contributions and 67 with 37 years' contributions. The shift from 65 to 67 is being made gradually between 2013 and 2027.

In many countries when a disability pension beneficiary reaches statutory retirement age, their disability benefits are classified as retirement benefits. This is known as “pension reclassification”.

We also used an R Package for Mortality Rates Graduation by Discrete Beta Kernel Techniques (Mazza and Punzo, 2014). The results are very similar. The package uses univariate and bivariate adaptive discrete beta kernel estimators. The number of deaths follows a binomial distribution.

Full details in Camarda (2012).

According to Scherbov and Ediev (2011), Chiang’s method can be used without significant problems with population sizes from about 10,000 upwards.

References

Amaducci, L., Maggi, S., Langlois, J., Minicuci, N., Baldereschi, M., Di Carlo, A., & Grigoletto, F. (1998). Education and the risk of physical disability and mortality among men and women aged 65 to 84: the Italian longitudinal study on aging. Journal of Gerontology, 53(6), 484–490

Belloni, M., Alessie, R., Kalwij, A., & Marinacci, C. (2013). Lifetime income and old age mortality risk in Italy over two decades. Demographic Research, 29, 1261–1298

Bosley, T.; M. Morris and K. Glenn (2018). Mortality by Career-Average Earnings Level. Actuarial study, 124. Social Security Administration, Office of the Chief Actuary. https://www.ssa.gov/OACT/NOTES/pdf_studies/study124.pdf

Breeze, E., Fletcher, A. E., Leon, D. A., Marmot, M., Clarke, R. J., & Shipley, M. J. (2001). Do socioeconomic disadvantages persist into old age? Self-reported morbidity in a 29-year follow-up of the Whitehall study. American Journal of Public Health, 91(2), 277–283

Camarda, C. G. (2012). Mortalitysmooth: An R package for smoothing poisson counts with P-splines. Journal of Statistical Software, 50, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v050.i01.

Camarda, C. G. (2020). Life Expectancy Confidence Interval. Carlo Giovanni Camarda - Personal page - R-stuff. Retrieved from: https://sites.google.com/site/carlogiovannicamarda/r-stuff/life-expectancy-confidence-interval. Accessed 21 May 2020.

Chiang, C.L. (1984). The Life Table and its Applications, Malabar, FL: Robert E. Krieger Publishers.

Dahl, E., & Birkelund, E. G. (1997). Health inequalities in later life in a social democratic welfare. Social Science and Medicine, 44(6), 871–881

Damian, J., Ruigomez, A., Pastor, V., & Martin-Moreno, J. M. (1999). Determinants of self-assessed health among Spanish older people living at home. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 53, 412–416

Dirección General de Ordenación de la Seguridad Social (DGOSS) (2019). Informe económico-financiero a los Presupuestos de la Seguridad Social de 2019. Gobierno de España. Ministerio de Trabajo, Migraciones y Seguridad Social. Secretaría de Estado de la Seguridad Social. http://www.seg-social.es/wps/wcm/connect/wss/3aa925cb-ece2-4477-acbf-7e3f853d8977/TOMO+III.-+INFORME+ECONOMICO-FINANCIERO-P.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CVID= Accessed 21 June 2020.

Dudel, C., López Gómez, M. A., Benavides, F. G., et al. (2018). The length of working life in Spain: Levels, recent trends, and the impact of the financial crisis. European Journal of Population, 34, 769–791. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-017-9458-9

Head, J., Chungkham, H. S., Hyde, M., Zaninotto, P., Alexanderson, K., Stenholm, S., Salo, P., Kivimäki, M., Goldberg, M., Zins, M., Vahtera, J., & Westerlund, H. (2019). Socioeconomic differences in healthy and disease-free life expectancy between ages 50 and 75: A multi-cohort study. European Journal of Public Health, 29, 267–272

Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE) (2020). Population mortality tables for Spain by year, sex, age and functions. https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Tabla.htm?t=27153&L=1 Accessed 22 July 2020

Kalwij, A., Alessie, R., & Knoef, M. (2013). The association between individual income and remaining life expectancy at the age of 65 in the Netherlands. Demography, 50(1), 181–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-012-0139-3

Kibele, E. U. B., Jasilionis, D., & Shkolnikov, V. M. (2013). Widening socioeconomic differences in mortality among men aged 65 years and older in Germany. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 67(5), 453–457

Kulhánová, I., Bacigalupe, A., Eikemo, T. A., Borrell, C., Regidor, E., Esnaola, S., Mackenbach, J. P., & Eurothine consortium (2014). Why does Spain have smaller inequalities in mortality? An exploration of potential explanations. European journal of public health, 24(3), 370–377. DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cku006

Lallo, C., & Raitano, M. (2018). Life expectancy inequalities in the elderly by socioeconomic status: evidence from Italy. Population Health Metrics, 16(1), 7

Li, N. (2015). The probabilistic life table and its applications to Canada. Canadian Studies in Population, 42(1–2), 117–129

Longevity Science Panel (2018). Life expectancy: Is the socio-economic gap narrowing? http://www.longevitypanel.co.uk/viewpoint/life-expectancy-is-the-socio-economic-gap-narrowing. Accessed 16 April 2020.

Longevity Science Panel (2020). An analysis of mortality trends in developed countries, focusing on the recent slowdown in mortality improvements. https://www.longevitypanel.co.uk/_files/LSP2020_Report.pdf. Accessed 16 April 2020.

Luy, M., Wegner-Siegmundt, C., Wiedemann, A., & Spijker, J. (2015). Life expectancy by education, income, and occupation in Germany: estimations using the longitudinal survival method. Comparative Population Studies, 40(4), 399–436

Mackenbach, J. P., Bopp, M., Deboosere, P., et al. (2017). Determinants of the magnitude of socioeconomic inequalities in mortality: A study of 17 European countries. Health & Place, 2017(47), 44–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2017.07.005

Mazza, A., & Punzo, A. (2014). DBKGrad: An R package for mortality rates graduation by discrete beta kernel techniques. Journal of Statistical Software, 57(2), 1–18

Ministerio de Trabajo y Economía Social (MTES). (2020). Anuario de Estadísticas 2018. Pensiones Contributivas del Sistema de la Seguridad Social. Gobierno de España. https://www.mites.gob.es/ficheros/ministerio/estadisticas/anuarios/2018/PEN/PEN.pdf.

Mc Munn, A., Breeze, E., Goodman, A., Nazroo, J., & Oldfield, Z. (2006). Social determinants of health in older age. In M. Marmot & R. G. Wilkinson (Eds.), Social determinants of health. (2nd ed., pp. 267–296). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Okamoto, S., Okamura, T., & Komamura, K. (2018). Employment and health after retirement in Japanese men. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 96, 826–833. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.18.215764

Parker, M., Bucknall, M., Jagger, C., & Wilkie, R. (2020). Population-based estimates of healthy working life expectancy in England at age 50 years: analysis of data from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Lancet Public Health, 5, 395–403

Pensioners and annuitants working group (PAWG) (2012). Pensioners and annuitants in Italy: Mortality from 1980 to 2009 and projections to 2040. Italian Actuarial Profession bodies (Consiglio dell’Ordine Nazionale degli Attuari e Consiglio Nazionale degli Attuari).

Pérez-Salamero Gonzalez, J. M., Regúlez-Castillo, M., & Vidal-Meliá, C. (2017). The continuous sample of working lives: Improving its representativeness. SERIEs. Journal of the Spanish Economic Association, 8, 43–95

Piłat, A., Galaś, A., Wilga, M., Cabello, M., Koskinen, S., Haro, J. M., & Tobiasz-Adamczyk, B. (2020). Gender perspective in the analysis of the relationship between health and work cessation, and how to deal with it. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health, 33(3), 365–384. https://doi.org/10.13075/ijomeh.1896.01351

Polvinen, A., Laaksonen, M., Gould, R., Lahelma, E., Leinonen, T., & Martikainen, P. (2015). Socioeconomic inequalities in cause-specific mortality after disability retirement due to different diseases. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 43, 159–168

Regidor, E., Kunst, A. E., Rodríguez-Artalejo, F., & Mackenbach, J. P. (2012). Small socio-economic differences in mortality in Spanish older people. The European Journal of Public Health, 22(1), 80–85

Scherbov, S., & Ediev, D. (2011). Significance of life table estimates for small populations: Simulation based study of standard errors. Demographic Research, 24, 527–550

Seguridad Social (2020a). Muestra Continua de Vidas Laborales. Seguridad Social -Estadísticas, Presupuestos y Estudios–Estadísticas. : http://www.seg-social.es/wps/portal/wss/internet/EstadisticasPresupuestosEstudios/Estadisticas/EST21. Accessed 21 Jun 2020.

Seguridad Social (2020b). Estadísticas. Seguridad Social -Estadísticas, Presupuestos y Estudios: http://www.seg-social.es/wps/portal/wss/internet/EstadisticasPresupuestosEstudios/Estadisticas Accessed 21 Jun 2020.

Solé-Auró, A., Martín, U., & Domínguez Rodríguez, A. (2020). Educational inequalities in life and healthy life expectancies among the 50-Plus in Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17, 3558. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103558

Steel, N., Huppert, F. A., McWilliams, B., & Melzer, D. (2003). Physical and cognitive function. In M. Marmot, J. Banks, R. Blundell, C. Lessof, & J. Nazroo (Eds.), Health, wealth and lifestyles of the older population in England: The 2002 English longitudinal study of ageing. (pp. 249–271). Institute for fiscal studies.

Stringhini, S., Carmeli, C., Jokela, M., Avendaño, M., Muennig, P., Guida, F., Ricceri, F., d’Errico, A., Barros, H., Bochud, M., Chadeau-Hyam, M., Clavel-Chapelon, F., Costa, G., Delpierre, C., Fraga, S., Goldberg, M., Giles, G. G., Krogh, V., Kelly-Irving, M., … Kivimäki, M. (2017). Socioeconomic status and the 25×25 risk factors as determinants of premature mortality: A multicohort study and meta-analysis of 1,7 million men and women. Lancet, 389, 1229–1237

Tanaka, H., Miyawaki, A., Toyokawa, S., & Kobayashi, Y. (2018). Relationship of relative poverty and social relationship on mortality around retirement: A 10-year follow-up of the Komo-Ise cohort. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine, 23(1), 64

Tetzlaff, F., Epping, J., Sperlich, S., & Tetzlaff, J. (2020). Widening income inequalities in life expectancy? Analysing time trends based on German health insurance data. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 74, 592–597. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2019-212966.

Thorslund, M., & Lundberg, O. (1994). Health and inequalities among the oldest old. Aging and Health, 6, 51–69

Toivanen, S., Griep, R. H., Meller, C., Vinberg, S., & Eloranta, S. (2016). Mortality differences between self-employed and paid employees: a 5-year follow-up study of the working population in Sweden. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 73, 627–636

Urbanaviciute, I., De Witte, H., & Rossier, J. (2019). Perceived job insecurity and self-rated health: testing reciprocal relationships in a five-wave study. Social Science Medicine, 233, 201–207

Waldron, H. (2007). Trends in mortality differentials and life expectancy for male social security-covered workers, by socioeconomic status. Social Security Bulletin, 67(3), 1–28

Wen, J., Kleinow, T., & Cairns, A. J. G. (2020). Trends in canadian mortality by pension level: Evidence from the CPP and QPP. North American Actuarial Journal, 24, 533–561. https://doi.org/10.1080/10920277.2019.1679190.

Wenau, G., Grigoriev, P., & Shkolnikov, V. (2019). Socioeconomic disparities in life expectancy gains among retired german men, 1997–2016. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 73, 605–611

Wu, C., Odden, M. C., Fisher, G., & Stawski, R. S. (2016). Association of retirement age with mortality: a population-based longitudinal study among older adults in the USA. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 70(9), 917–923

Acknowledgements

The authors are especially grateful to David Atance del Olmo, who made an active contribution to previous versions, and to Peter Hall for his help with the English text. The comments and suggestions made by two anonymous referees were extremely helpful in improving the paper. Any errors are entirely due to the authors.

Funding

The authors are grateful for the financial assistance received from the Spanish Ministry of the Economy and Competitiveness (Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad), projects ECO2015-65826-P, RTI2018-097087-B-100, the Generalidad Valenciana (Valencian Government), project AICO/2019/075, and the Basque Government, project IT1336-19.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.M.P.-S.G. contributed to data curation; M.R.-C. and C.V.-M. contributed to formal analysis; J.M.P.-S.G., M.R.-C. and C.V.-M. contributed to investigation; C.V.-M. contributed to methodology; J.M.P.-S.G. and M.R.-C. contributed to software; M.R.-C. and C.V.-M. contributed to writing—original draft; J.M.P.-S.G., M.R.-C. and C.V.-M contributed to writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no financial interests. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval is not required to use CSWL; its use for scientific purposes is regulated since inception.

Consent to participate

All authors consent to participate in this process.

Consent for publication

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: an alternative approach to building confidence intervals

Appendix: an alternative approach to building confidence intervals

An alternative approach used to build life expectancy confidence intervals is based on Camarda (2012). To be specific, we modify the R routine (LifeTableFUN.R) provided by Camarda (2020) using the bootstrap method. In this process we use the function \(rbinom(m\cdot {n}_{s}, Ntil,{ q}_{x})\)) to generate life table deaths, Y, where m are the number of ages (65–101), \({n}_{s}\) the number of random samples, in this case 1000, \(Ntil = round({ D}_{x}/{ q}_{x})\), where \({D}_{x}\) is the number of observed deaths at age x and \({q}_{x}\) the smoothed observed probabilities of death. Then we construct the simulated probabilities, \({Q}_{x} = Y/Ntil\), to be used to generate simulated life tables and, as a product of the \({n}_{s}\), simulated life expectancies at a given age, \({\mathrm{SLE}}_{\mathrm{X}(\mathrm{i})}, i=1,..., {n}_{s}\). Using the sample distribution of these \({n}_{s}\) replicates, we then construct the confidence interval for a given quantile.

Following Li (2015), we use the simulated life expectancies obtained from Camarda´s bootstrapping procedure to test whether a life table variable, in this case life expectancy at age 65 for one pension income group,\({\mathrm{LE}}_{65}^{2}\), is bigger than the same variable for another pension income group, \({\mathrm{LE}}_{65}^{1}\) i.e. whether such a difference is statistically significant or whether it may appear purely by random chance.

We will denote by the use of \({\mathrm{SLE}}_{65(\mathrm{i})}^{1}\) and \({\mathrm{SLE}}_{65(\mathrm{i})}^{2},\) \(i=1,..., {n}_{s}\) the simulated life expectancy for each group at age 65. Since the \(i\) is chosen independently for \({\mathrm{SLE}}_{65(\mathrm{i})}^{1}\) and \({\mathrm{SLE}}_{65(\mathrm{i})}^{2},\) the sample distribution of z can be computed as:

\(i=1,...,{n}_{s}\) where \({\widehat{{\sigma }_{1}}}^{2}\) and \({\widehat{{\sigma }_{2}}}^{2}\) can be computed from the sample distributions as:

Using the sample distribution of z, we can find the 95% confidence interval, namely \([{c}_{1},{c}_{2}]\), not exactly but approximately. The test statistic of the observed value \(z\) is

where \({\widehat{{\sigma }_{1}}}^{2}\) and \({\widehat{{\sigma }_{2}}}^{2}\) are the estimated variances of \({\mathrm{LE}}_{65}^{1}\) and \({\mathrm{LE}}_{65}^{2}\), which can be computed from the sample distributions as above.

If \(z\) falls outside \([{c}_{1},{c}_{2}]\), then the null hypothesis leads to an observation that occurs with a probability smaller than 0.05, and hence it is rejected at the 0.05 level. Moreover, if the test is a one-tailed test to the right, then for a given significance level we can calculate the critical value \({Z}_{\alpha }\) using the sample distribution of z such that \(Pr(z\le {Z}_{\alpha }) =1-\alpha\).

The main results of using this alternative methodology are shown in the following tables (Tables 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 and 16) and Figures (Figs. 6 and 7)

The robustness of the results is assured given that they are almost identical to what was seen in Sect. 3.

Table 10 is equivalent to Table 4 shown in Sect. 3.

Table 12 is equivalent to Table 5 shown in Sect. 3

Table 14 is equivalent to Table 6 shown in Sect. 3. Figure 6 illustrates the results shown in Table 14.

It shows the sample distributions of LE65 in P1 for some initial pension income groups of PE (Graph 1) and SE (Graph 2) beneficiaries. The probability distributions of LE65 are computed using 1000 simulations that capture the uncertainty in the survival process of these pension income groups.

Graph 1 shows that the DLE65 for PE beneficiaries is statistically significant at 1%, given that the 95% confidence intervals are not overlapping. Graph 2 shows that the two distributions are quite different, but the 95% confidence intervals are partly overlapping, indicating that statistical significance is attained at the higher level.

For PE beneficiaries, the simulated LE65 95% confidence intervals are (18.90–19.92) and (20.27–21.21), respectively, for the Low and High pension income groups. The DLE65 for the mean values is 1.37 years (20.74–19.37). For SE beneficiaries the simulated LE65 95% confidence intervals are (19.37–20.52) and (20.11–20.76), respectively, for the Low and Medium–Low pension income groups. The DLE65 for the mean values is 0.46 years (19.98–20.43)

Table 16 is equivalent to Table 7 shown in Sect. 3.

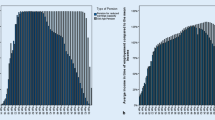

Figure 7 presents the histograms of the simulated LE65 for equivalent Low groups in P1 (Graph 1) and P3 (Graph 2). These are a useful graphic tool to enable a better understanding of the results shown in Table 16.

Graph 1 shows that some of the 95% confidence intervals for LE65 are overlapping, given that the values are (18.90–19.92) and (19.37–20.52), respectively, for PE and SE. This is why the level of statistical significance for DLE65 is at 10% in the one-tailed test in P1. Conversely, Graph 2 clearly shows that there is no overlap between the 95% confidence intervals for the simulated LE65 for equivalent low-income groups in P3. The simulated LE65 95% confidence intervals are (19.11–20.15) and (20.28–21.38), respectively, for PE and SE beneficiaries, and the DLE65 for the mean values is 1.19 years (20.82–19.63). This is why the DLE65 is statistically significant at 1% in the third period.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pérez-Salamero González, J.M., Regúlez-Castillo, M. & Vidal-Meliá, C. Differences in Life Expectancy Between Self-Employed Workers and Paid Employees when Retirement Pensioners: Evidence from Spanish Social Security Records. Eur J Population 37, 697–725 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-021-09585-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-021-09585-1