Abstract

Using retrospective life history data from the 2008 Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS), this study examines the entrance into first marriage in China, a country that has been experiencing profound socioeconomic changes for the past several decades. We examine educational differences across rural and urban regions and across gender as determinants of marriage. Results reveal that for rural women, increasing education (especially from the least educated to middle levels of education) decreases marriage chances. For urban women, increasing education does not affect their marriage chances, net of other factors. For the former, results are consistent with the broad East Asian cultural practice of women “marrying up.” For the latter, we argue that modernizing forces (e.g., improvements in education) have reduced the incidence of this practice. We also find effects attributable to unique features of the Chinese institutional context, such as the rural/urban divide and effects of the household registration (Hukou) system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We attempted to deal with this problem by adding period fixed effects (i.e., year dummy variables) to our model. Although researchers who developed age-period-cohort models (e.g., Yang and Land 2006) suggest that age, period, and cohort measures can simultaneously be included in a regression model, provided that (for example) age is introduced as a curvilinear effect, when we tried this approach, period measures were highly collinear with age and cohort measures. Although we were able to estimate the model, due to the collinearity issue we do not present it with our final results (although it is available on request). We note that, except for estimates related to cohort measures (which became nonsignificant), other estimates from that model matched those of our final model (e.g., Model 1), so period-specific factors had no particular bearing on our results.

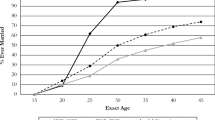

Unfortunately, this strategy introduced collinearity between the main effect of age and its squared term. We attempted to diminish this problem by mean-centering the age variable before taking its square, but doing so created convergence problems in some models, so we ultimately abandoned this approach. In a separate set of models, we used a linear spline with knots at 25 and 30 years of age. Differences in the slope of all age coefficients were statistically significant, and confirmed a curvilinear pattern of marriage by age.

Indeed, the error bar for rural women with a rural Hukou is particularly large, consistent with the notion that high levels of education there were uncommon, therefore increasing the uncertainty in the coefficient estimate.

References

Allison, P. D. (1982). Discrete-time methods for the analysis of event histories. Sociological Methodology, 13(1), 61–98.

Allison, P. D. (1995). Analysis using SAS system: A practical guide. Cary: SAS Institute.

Becker, G. S. (1981). A treatise on the family. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Bian, Y., & Logan, J. R. (1996). Market transition and the persistence of power: The changing stratification system in urban China. American Sociological Review, 61(5), 739–758.

Blossfeld, H. (2009). Educational assortative marriage in comparative perspective. Annual Review of Sociology, 35, 513–530.

Cai, Y., & Lavely, W. (2003). China’s missing girls: Numerical estimates and effects on population growth. China Review, 3(2), 13–29.

Chan, K. W., & Buckingham, W. (2008). Is China abolishing the Hukou system? China Quarterly, 195, 582–606.

Chan, K. W., & Zhang, L. (1999). The Hukou system and rural–urban migration in China: Processes and changes. China Quarterly, 160, 818–855.

Choe, M. K. (2006). Modernization, gender roles, and marriage behavior in South Korea. In Y. Chang & S. Lee (Eds.), Transformations in twentieth century Korea (pp. 291–309). New York: Routledge.

Cox, D. R., & Oakes, D. (1984). Analysis of survival data. Boca Raton: Chapman and Hall/CRC.

Cumming, G., & Finch, S. (2005). Confidence intervals and how to read pictures of data. American Psychologist, 60(2), 170–180.

Diamant, N. J. (2000). Revolutionizing the family: Politics, love, and divorce in urban and rural China, 1949–1968. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Fan, C., & Huang, Y. (1998). Waves of rural brides: Female marriage migration in China. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 88(2), 227–251.

Frejka, T. (2008). Determinants of family formation and childbearing during the societal transition in Central and Eastern Europe. Demographic Research, 19(7), 139–170.

Frejka, T., Jones, G. W., & Sardon, J. (2010). East Asian childbearing patterns and policy developments. Population and Development Review, 36(3), 579–606.

Glenn, N. D. (2003). Distinguishing age, period, and cohort effects. In J. T. Mortimer & M. J. Shanahan (Eds.), Handbook of the life course (pp. 465–476). New York: Springer.

Goode, W. J. (1963). World revolution and family patterns. Glencoe: Free Press.

Han, H. (2010). Trends in educational assortative marriage in China from 1970 to 2000. Demographic Research, 22(24), 733–770.

Hannum, E. (1999). Political change and the urban–rural gap in basic education in China, 1949–1990. Comparative Education Review, 43(2), 193–211.

Hauser, S. M., & Xie, Y. (2005). Temporal and regional variation in earnings inequality: Urban China in transition between 1988 and 1995. Social Science Research, 34(1), 44–79.

Hou, F., & Myles, J. (2008). The Changing role of education in the marriage market: Assortative marriage in Canada and the United States since the 1970s. The Canadian Journal of Sociology, 33(2), 337–366.

Inglehart, R., & Baker, W. E. (2000). Modernization, cultural change, and the persistence of traditional values. American Sociological Review, 65(1), 19–51.

Ji, Y., & Yeung, W. J. J. (2014). Heterogeneity in contemporary Chinese marriage. Journal of Family Issues, 35(12), 1662–1682.

Jin, X., Li, S., & Feldman, M. W. (2005). Marriage form and age at first marriage: A comparative study in three counties in contemporary rural China. Biodemography and Social Biology, 52(1–2), 18–46.

Jones, G. W. (2004). Not “when to marry” but “whether to marry”: The changing context of marriage decisions in East and Southeast Asia. In G. Jones & K. Ramdas (Eds.), Untying the knot: Ideal and reality in Asian marriage (pp. 3–58). Singapore: Asia Research Institute.

Jones, G. W. (2005). The “flight from marriage” in South-East and East Asia. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 36(1), 93–119.

Kalmijn, M. (2007). Explaining cross-national differences in marriage, cohabitation, and divorce in Europe, 1990–2000. Population Studies, 61(3), 243–263.

Knight, J. (2008). Reform, growth, and inequality in China. Asian Economic Policy Review, 3(1), 140–158.

Knight, J., Shi, L., & Song, L. (2006). The rural–urban divide and the evolution of political economy in China. In J. K. Boyce, S. Cullenberg, P. K. Pattanaik, & R. Pollin (Eds.), Human development in the era of globalization: Essays in honor of Keith B. Griffin (pp. 44–63). Northampton: Edward Elgar.

Lester, D. (1996). Trends in divorce and marriage around the world. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 25(1–2), 169–171.

Lesthaeghe, R. (2010). The unfolding story of the second demographic transition. Population and Development Review, 36(2), 211–251.

Li, B., & Walder, A. G. (2001). Career advancement as party patronage: Sponsored mobility into the Chinese administrative elite, 1949–1996. American Journal of Sociology, 106(5), 1371–1408.

Liang, Z. (2001). The age of migration in China. Population and Development Review, 27(3), 499–524.

Long, S. J. (1997). Regression models for categorical and limited dependent variables. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Mason, K. O. (1997). Explaining fertility transitions. Demography, 34(4), 443–454.

Nee, V., & Matthews, R. (1996). Market transition and societal transformation in reforming state socialism. Annual Review of Sociology, 22, 401–435.

Nemoto, K. (2008). Postponed marriage: Exploring women’s views of matrimony and work in Japan. Gender and Society, 22(2), 219–237.

Nie, H., & Xing, C. (2011). When city boy falls in love with country girl: Baby’s Hukou, Hukou reform, and inter-Hukou marriage. Paper presented at the Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) annual workshop, Bonn, Germany.

Ono, H. (2003). Women’s economic standing, marriage timing, and cross-national contexts of gender. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65(2), 275–286.

Oppenheimer, V. K. (1988). A theory of marriage timing. American Journal of Sociology, 94(3), 563–591.

Parsons, T., & Bales, R. F. (1955). Family socialization and interaction process. Glencoe: Free Press.

Raley, R. K. (2000). Recent trends and differentials in marriage and cohabitation: The United States. In L. Waite, C. Bachrach, M. Hindin, E. Thomson, & A. Thornton (Eds.), The ties that bind: Perspectives on marriage and cohabitation (pp. 19–39). New York: Walter de Gruyter.

Raymo, J. M. (2003). Educational attainment and the transition to first marriage among Japanese women. Demography, 40(1), 83–103.

Raymo, J. M., & Iwasawa, M. (2005). Marriage market mismatches in Japan: An alternative view of the relationship between women’s education and marriage. American Sociological Review, 70(5), 801–822.

Rindfuss, R. R., Choe, M. K., Bumpass, L. L., & Tsuya, N. O. (2004). Social networks and family change in Japan. American Sociological Review, 69(6), 838–861.

Rindfuss, R. R., Palmore, J. A., & Bumpass, L. L. (1982). Selectivity and the analysis of birth intervals from survey data. In Asian and Pacific census forum (pp. 5–6). Honolulu, Hawaii: East-West Center.

Rubin, Z. (1968). Do American women marry up? American Sociological Review, 33(5), 750–760.

Ryder, N. B. (1965). The cohort as a concept in the study of social change. American Sociological Review, 30(6), 843–861.

Schwartz, C. R., & Mare, R. D. (2005). Trends in educational assortative marriage from 1940 to 2003. Demography, 42(4), 621–646.

Shafer, K., & Qian, Z. (2010). Marriage timing and educational assortative mating. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 41(5), 661–691.

Smits, J., & Park, H. (2009). Five decades of educational assortative mating in 10 East Asian societies. Social Forces, 88(1), 227–255.

Song, L. (2009). The effect of the cultural revolution on educational homogamy in urban China. Social Forces, 88(1), 257–270.

Sweeney, M. M. (2002). Two decades of family change: The shifting economic foundations of marriage. American Sociological Review, 67(1), 132–147.

Thornton, A. (2001). The developmental paradigm, reading history sideways, and family change. Demography, 38(4), 449–465.

Tian, F. F. (2013). Transition to first marriage in reform-era urban china: The persistent effect of education in a period of rapid social change. Population Research and Policy Review, 32(4), 529–552.

Torr, B. M. (2011). The changing relationship between education and marriage in the United States, 1940–2000. Journal of Family History, 36(4), 483–503.

Treiman, D. J. (2013). Trends in educational attainment in China. Chinese Sociological Review, 45(3), 3–25.

Trent, K., & South, S. J. (2011). Too many men? Sex ratios and women’s partnering behavior in China. Social Forces, 90(1), 247–267.

Tsuya, N. O., & Bumpass, L. L. (2004). Marriage, work, and family life in comparative perspective: Japan, South Korea, and the United States. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

White, H. (1980). A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 48(4), 817–838.

Xia, Y. R., & Zhou, Z. G. (2003). The transition of courtship, mate selection and marriage in China. In R. R. Hamon & B. B. Ingoldsby (Eds.), Mate selection across cultures (pp. 231–246). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Xie, Y., & Hannum, E. (1996). Regional variation in earnings inequality in reform-era urban China. American Journal of Sociology, 101(4), 950–992.

Yang, Y., & Land, K. C. (2006). A mixed models approach to the age-period-cohort analysis of repeated cross-section surveys, with an application to data on trends in verbal test scores. Sociological Methodology, 36(1), 75–97.

Yu, J., & Xie, Y. (2013). Social change and trends in determinants of entry to first marriage. Sociological Research, 4, 1–25 (in Chinese).

Acknowledgments

Piotrowski’s efforts on this research were supported in part by a Faculty Enrichment Grant from the University of Oklahoma. Piotrowski would like to thank the Carolina Population Center (CPC) and the East West Center (EWC) for providing office space and other resources during the writing of this paper. Chao received a Grasmick fellowship from the Sociology Department of the University of Oklahoma to support his contribution to this paper. The authors would like to thank Susanne Choi, S. Philip Morgan, and Ronald R. Rindfuss for helpful comments on earlier versions of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

See Table 3.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Piotrowski, M., Tong, Y., Zhang, Y. et al. The Transition to First Marriage in China, 1966–2008: An Examination of Gender Differences in Education and Hukou Status. Eur J Population 32, 129–154 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-015-9364-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-015-9364-y