Abstract

Little is known about fertility in Armenia and Moldova, the two countries that have both, according to national statistics, experienced very low levels of fertility during the dramatic economic, social and political restructuring in the last two decades. This article fills this gap and explores recent fertility behaviour and current fertility preferences using 2005 Demographic and Health Survey data. Educational differences in fertility decline and the association between socioeconomic indicators and fertility preferences are considered from an economic perspective. Special emphasis is given to determining whether and how diverging economic conditions in the two countries as well as crisis conditions may have influenced fertility. Second parity progression ratios (PPR) reveal a positive relationship between the degree of decline from 1990 to 2005 and education, whereas third PPR declines appear the greatest for women with both the lowest and highest education. In both countries, logistic regression results suggest that working women are more likely to want a second child, as well as want the child sooner university than later in Armenia, and the wealthiest women in Armenia have a higher odds of wanting a third child. Dual-jobless couples are less likely to want a second child in Moldova and more likely to postpone the next child in Armenia. These findings offer some insight into the shifts in fertility behaviour in these two post-Soviet countries and suggest that despite diverging economic trajectories and a lessening commitment to the two-child norm in Moldova, determinants of fertility behaviour and preferences have remained similar in both countries.

Résumé

Il y a peu d’informations sur la fécondité en Arménie et en Moldavie, deux pays qui, selon leurs statistiques nationales, ont connu de très faibles niveaux de fécondité durant la spectaculaire restructuration économique, sociale et politique survenue au cours de ces deux dernières décennies. Cet article vise à combler ce vide et analyse les comportements de fécondité récents et les préférences actuelles de fécondité à partir de données de l’enquête démographique et de santé de 2005. Les différences de fécondité selon le niveau d’instruction et l’association entre les indicateurs socioéconomiques et les préférences en matière de fécondité sont étudiées sous un angle économique. Une attention particulière est apportée aux situations économiques divergentes des deux pays ainsi qu’aux caractéristiques de la crise afin de déterminer si ces deux facteurs ont pu influencer la fécondité et de quelle manière. Les probabilités d’agrandissement du premier au deuxième enfant montrent une relation positive entre l’ampleur du déclin entre 1990 et 2005 et le niveau d’instruction, alors que la diminution des probabilités d’agrandissement du deuxième au troisième enfant est la plus importante chez les femmes ayant le niveau d’instruction soit le plus faible, soit le plus élevé. Les résultats de régressions logistiques réalisées suggèrent que dans les deux pays les femmes qui travaillent sont plus disposées à vouloir un deuxième enfant, qu’en Arménie elles souhaitent avoir cet enfant plus tôt, et que les femmes les plus aisées en Arménie ont une probabilité plus élevée de vouloir un troisième enfant. Les couples de chômeurs sont moins disposés à vouloir un deuxième enfant en Moldavie et plus disposés à retarder la venue du prochain enfant en Arménie. Ces résultats donnent un aperçu des modifications des comportements de fécondité dans ces pays après la période soviétique et suggèrent qu’en dépit de trajectoires économiques différentes et d’une moindre adhésion à la norme de deux enfants en Moldavie, les déterminants des comportements et des préférences en matière de fécondité sont restés semblables dans les deux pays.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See, for example, Bulgaria: Bühler and Philipov (2005), Philipov et al. (2006), Philipov and Jasilioniene (2007); Czech Republic: Kantorová (2004), Klasen and Launov (2006), Sobotka (2003); Hungary: Oláh and Fratczak (2004), Philipov et al. (2006), Spéder (2006); Poland: Bühler and Fratczak (2007), Kotowska et al. (2008); Romania: Muresan and Hoem (2009), Rotariu (2006); Slovakia: Potančoková et al. (2008); Slovenia: Stropnik and Šircelj (2008).

Russia is an exception (see Billingsley 2010a; Bühler 2004; Gerber and Cottrell 2006; Kharkova and Andreev 2000; Kohler and Kohler 2002; Perelli-Harris 2006), and a few analyses have documented changes in Ukraine (Perelli-Harris 2005; 2008), Estonia (Katus 2000; Klesment and Puur 2010), Lithuania (Stankuniene and Jasilioniene 2008) and in a few Central Asian Republics (Agadjanian et al. 2008; Agadjanian and Makarova 2003).

This estimation is much higher than what official reports claim, indicating that either the DHS samples are not representative or official statistics were calculated with incorrect information. The first possibility is unlikely due to the nature of the DHS sample selection design, but the latter explanation is highly possible, especially in turbulent times, when migration is difficult to monitor and, thus, the denominator in calculating age-specific fertility rates may be incorrect.

This source excludes the lower rates of Transnistria.

Without longitudinal data, the possibilities for investigating the relationships of other individual characteristics and fertility behaviour over the 1990s and early 2000s are limited.

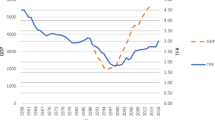

Note that the unemployment rates were calculated differently in the two countries, but the most comparable statistics were presented. Armenian rates are official estimates based on registered unemployment of ages 16–63 and Moldova’s rates are calculated with Labor Force Survey data for all individuals over the age of 15.

The Armenian report in the SSW explicitly states that ‘Benefits are adjusted on an ad hoc basis according to available resources’.

Unfortunately, the non-working population cannot be separated into those that are unemployed and those that are not participating in the labour force on the basis of DHS data.

To ensure that the data represent the country proportionally, according to geographical population density, and to prevent any bias due to geographical clustering, a sampling weight was used as well as Stata’s package of survey commands.

These analyses also remain descriptive, however, in the sense that findings are cross sectional and limited to interpretation as associations only.

Similar to the last empirical analysis of changes in fertility patterns according to educational levels, an issue of sequencing exists. Howecer, as previously discussed, this issue is more problematic when discussing first births rather than higher parity births, as is the case here.

These figures are available upon request.

Sensitivity analyses, in which the undecided were placed with those who do not want another child, were conducted to make sure this decision did not alter the major findings.

Non-numerical responses (3.5% in Armenia and 4% in Moldova) refer to answers such as ‘after we get married’. Since there is no unequivocal logic to placing these answers with ‘sooner’ or ‘later’, they are coded as later and sensitivity analyses confirm that this small portion of respondents does not change the overall results if they are coded alternatively as sooner.

The time passed since the last birth is also included in the first model predicting desire for another child.

The questions from the survey are the following: ‘Aside from your own housework, have you done any work in the last 7 days?’ ‘As you know, some women take up jobs for which they are paid in cash or kind. Others sell things, have a small business or work on the family farm or in the family business. In the last 7 days, have you done any of these things or any other work?.’

An obvious positive relationship emerges for wealth and education as well, but these findings are not shown for reasons of space.

Looking into the characteristics of these couples reveals little variation in wealth by joint employment status in Armenia, whereas significant differences in wealth exist in Moldova for those who are neither or both employed.

The only other substantive change involved in this kind of different operationalisation is that having a working partner becomes statistically significant and has a positive effect on timing in Moldova.

References

Agadjanian, V., Dommaraju, P., & Glick, J. (2008). Reproduction in upheaval: Crisis, ethnicity, and fertility in Kazakhstan. Population Studies, 62(2), 211–233.

Agadjanian, V., & Makarova, E. (2003). From Soviet modernization to post-Soviet transformation: Understanding marriage and fertility dynamics in Uzbekistan. Development and Change, 34(3), 447–473.

Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behaviour. In J. Kuhl & J. Beckman (Eds.), Action control: From cognition to behaviour. New York: Springer.

Asatryan, G., & Arakelova, V. (2002). The ethnic minorities of Armenia. Document from the Human Rights in Armenia. Civil Society Institute, Yerevan. http://www.hra.am/file/minorities_en.pdf.

Avdeev, A., Blum, A., & Troitskaya, I. (1995). The history of abortion statistics in Russia and the USSR from 1900 to 1991. Population: An English Selection, 7, 39–66.

Barrett, D. B., Kurian, G. T., & Johnson, T. M. (2001). World Christian encyclopedia. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Becker, G. (1981). A treatise on the family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Billingsley, S. (2010a). Downward social mobility and fertility in Russia. Stockholm Research Reports in Demography, 2010, 1.

Billingsley, S. (2010b). The post‐communist fertility puzzle. Population Research and Policy Review, 29(2), 193–231.

Blake, J. (1967). Family size in the 1960s—a baffling fad? Eugenics Quarterly, 14(1), 60–74.

Bongaarts, J. (2001). Fertility and reproductive preferences in post-transitional societies. Population and Development Review, 27(Supplement), 260–281.

Bongaarts, J. (2002). The end of fertility transition in the developed world. Population and Development Review, 28, 419–444.

Bühler, C. (2004). Additional work, family agriculture, and the birth of a first or a second child in Russia at the beginning of the 1990s. Population Research and Policy Review, 23(3), 259–289.

Bühler, C., & Fratczak, E. (2007). Learning from others and receiving support: The impact of personal networks on fertility intentions in Poland. European Societies, 9(3), 359–382.

Bühler, C., & Philipov, D. (2005). Social capital related to fertility: Theoretical foundations and empirical evidence from Bulgaria. Vienna yearbook of population research. Vienna: Austrian Academy of Sciences Press.

Bulgaru, M., Bulgaru, O., Sobotka, T., & Zeman, K. (2000). Past and present population development in the Republic of Moldova. In T. Kučera, O. Kučerová, & O. Opara (Eds.), New demographic faces of Europe. The changing population dynamics in countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Danielyan, E. (2006). Survey highlights Armenia’s lingering unemployment. Armenia Liberty. http://www.armenialiberty.org/content/Article/1580435.html.

Fajth, G. (1999). Social security in a rapidly changing environment: The case of the post-communist transformation. Social Policy and Administration, 33(4), 416–436.

Frejka, T. (2008). Determinants of family formation and childbearing during the societal transition in Central and Eastern Europe. In T. Frejka, T. Sobotka, J. M. Hoem, & L. Toulemon (Eds.), Childbearing trends and policies in Europe (pp. 130–170). Demographic Research, Series no. 7.

Gerber, T., & Cottrell, E. B. (2006). Fertility in Russia, 1985–2001. Insights from individual fertility histories. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America, Los Angeles.

Hinde, A. (1998). Demographic methods. London: Arnold.

Hotz, V. J., Klerman, J. A., & Willis, R. (1997). The economics of fertility in developed countries. In M. R. Rosenzweig & O. Stark (Eds.), Handbook of population and family economics. Amsterdam: Elsevier science.

Kantorová, V. (2004). Education and entry into motherhood: The Czech Republic during state socialism and the transition period (1970–1997). Demographic Research, S3(10), 245–272.

Katus, K. (2000). General patterns of post-transitional fertility in Estonia. Trames, 3, 213–230.

Kharkova, T., & Andreev, E. (2000). Did the economic crisis cause the fertility decline in Russia: Evidence from the 1994 Microcensus. European Journal of Population, 16, 211–233.

Klasen, S., & Launov, A. (2006). Analysis of the determinants of fertility decline in the Czech Republic. Journal of Population Economics, 19(1), 25–54.

Klesment, M., & Puur, A. (2010). Effects of education on second births before and after societal transititon: Evidence from the Estonian GGS. Demographic Research, 22, 891–932.

Kohler, H. P., Billari, F., & Ortega, J. (2002). The emergence of lowest-low fertility in Europe. Population and Development Review, 28(4), 641–680.

Kohler, H. P., & Kohler, I. (2002). Fertility decline in Russia in the early and mid 1990s: The role of economic uncertainty and labour market crises. European Journal of Population, 18, 233–262.

Kotowska, I. E., Jóźwiak, J., Matysiak, A., & Baranowska, A. (2008). Poland: Fertility decline—a response to profound societal change and transformations in the labour market? Demographic Research, S7(22), 795–854.

Koytcheva, E. (2006). Social-demographic differences of fertility and union formation in Bulgaria before and after the start of the societal transition. Doctoral dissertation published by Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research.

Laborsta. (2010). Laborsta Internet, main statistics, annual. ILO website. http://laborsta.ilo.org/STP/guest.

Lesthaeghe, R., & van de Kaa, R. (1986). Twee demografische transities? In D. van de Kaa & R. Lesthaeghe (Eds.), Bevolking: Groei en krimp. Deventer: Van Loghum Slaterus.

Moldovan National Bureau of Statistics. (2010). Population by main nationalities, mother tongue and language usually spoken. Moldovan National Bureau of Statistics website. http://www.statistica.md/pageview.php?l=en&idc=295&id=2234.

Muresan, C., & Hoem, J. M. (2009). The negative educational gradients in Romanian fertility. Demographic Research, 22(4), 95–114.

National Statistical Service (Armenia), Ministry of Health (Armenia), & ORC Macro. (2006). Armenia Demographic and Health Survey 2005. Calverton, Maryland: National Statistical Service, Ministry of Health, & ORC Macro.

National Statistical Service of Armenia. (2010). 2001 Population Census Factsheet. National Statistical Service of Armenia. http://docs.armstat.am/census/pdfs/51.pdf.

NCPM (National Scientific and Applied Center for Preventative Medicine, Moldova), & ORC Macro. (2006). Moldova Demographic and Health Survey 2005. Calverton, Maryland: National Scientific and Applied Center for Preventative Medicine of the Ministry of Health and Social Protection ORC Macro.

Nee, V. (1989). A theory of market transition: From redistribution to markets in state socialism. American Sociological Review, 54, 663–681.

Neyer, G., & Andersson, G. (2008). Consequences of family policies on childbearing behaviour: Effects or artifacts? Population and Development Review, 34(4), 699–724.

Ní Brolcháin, M. (1987). Period parity progression ratios and birth intervals in England and Wales, 1941–1971: A synthetic life table analysis. Population Studies, 41, 103–125.

Oláh, L., & Fratczak, E. (2004). Becoming a mother in Hungary and Poland during state socialism. Demographic Research, S3(9), 213–243.

Perelli-Harris, B. (2005). The path to lowest-low fertility in Ukraine. Population Studies, 59(1), 55–70.

Perelli-Harris, B. (2006). The influence of informal work and subjective well-being on childbearing in post-Soviet Russia. Population and Development Review, 32(4), 729–753.

Perelli-Harris, B. (2008). Family formation in post-Soviet Ukraine: Changing effects of education in a period of rapid social change. Social Forces, 87(2), 767–794.

Philipov, D. (2009). Fertility intentions and outcomes: The role of policies to close the gap. European Journal of Population, 25, 355–361.

Philipov, D., & Jasilioniene, A. (2007). Union formation and fertility in Bulgaria and Russia: A life table description of recent trends. Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research Working Paper 2007–2005.

Philipov, D., Spéder, Z., & Billari, F. (2006). Soon, later, or ever? The impact of anomie and social capital on fertility intentions in Bulgaria (2002) and Hungary (2001). Population Studies, 60(3), 289–308.

Potančoková, M., Vaňo, B., Pilinská, V., & Jurčová, D. (2008). Slovakia: Fertility between tradition and modernity. Demographic Research, 19(25), 973–1018.

Rindfuss, R. R., Cooksey, E. C., & Sutterlin, R. L. (1999). Young adult occupational achievement: Early expectations versus behavioral reality. Work & Occupations, 26, 220–263.

Rotariu, T. (2006). Romania and the Second Demographic Transition. The traditional value system and low fertility rates. International Journal of Sociology, 36(1), 10–27.

Rutstein, S., & Johnson, K. (2004). The DHS wealth index. DHS comparative reports no. 6. Calverton, Maryland: ORC Macro

Sarkissian, A. (2008). Religion in post-Soviet Armenia: Pluralism and identity formation in transition. Religion, State and Society, 36(2), 163–180.

Sobotka, T. (2003). Re-emerging diversity: Rapid fertility changes in Central and Eastern Europe after the collapse of the communist regimes. Population, 4–5(58), 451–486.

Spéder, Z. (2006). Rudiments of recent fertility decline in Hungary: Postponement, educational differences, and outcomes of changing partnership forms. Demographic Research, 15(8), 253–284.

Stankuniene, V., & Jasilioniene, A. (2008). Lithuania: Fertility decline and its determinants. Demographic Research, 19, 705–742.

Stropnik, N., & Šircelj, M. (2008). Slovenia: Generous family policy without evidence of any fertility impact. In T. Frejka, T. Sobotka, J. M. Hoem & L. Toulemon (Eds.), Demographic Research, Series no. 7, pp. 1019–1058.

Teplova, T. (2007). Welfare state transformation, childcare, and women’s work in Russia. Social Politics, 14, 284–322.

Thornton, A., Axinn, W. J., & Teachman, J. D. (1995). The influence of school enrollment and accumulation on cohabitation and marriage in early adulthood. American Sociological Review, 60(5), 762–774.

TransMonee. (2004–2006). TransMonee Database. Florence: UNICEF IRC.

Troitskaya, I., & Andersson, G. (2007). Transition to modern contraception in Russia: Evidence from the 1996 and 1999 Women’s Reproductive Health Surveys. Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, MPIDR Working paper WP 2007–2010, February.

Westoff, C., Sullivan, J., Newby, H., & Themme, A. (2002). Contraception—Abortion connections in Armenia. DHS analytical studies, no. 6. Calverton, Maryland: ORC Macro.

Acknowledgments

This research was carried out with support provided by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) through the MEASURE DHS project (#GPO-C-00-03-00002-00). This author would like to thank Macro International Inc., Demographic and Health Research Division for offering both financial and analytical support to complete this analysis and for their many helpful suggestions, especially from Simona Bignami, Sarah Bradley, Vinod Mishra and Rand Stoneburner. The author also would like to thank the Pompeu Fabra Universitat in Barcelona, Spain, for their continuous support during the research for this article. The analysis also benefited from comments by Pau Baizan, Gosta Esping-Andersen, Alexandra Pittman, Elizabeth Thomson, Sutay Yavuz and two anonymous reviewers of the European Journal of Population. The author alone is responsible for any of the errors in this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Billingsley, S. Second and Third Births in Armenia and Moldova: An Economic Perspective of Recent Behaviour and Current Preferences. Eur J Population 27, 125–155 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-011-9229-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-011-9229-y

Keywords

- Fertility preferences

- Parity progression

- Postponement

- Post-communist

- Economic explanations

- Armenia

- Moldova

- Higher-order births

- Post-communist

- Postponement

- Employment