Abstract

The latest report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) warns of an increase in heavy rainfall events due to global warming and climate change, which can result in significant economic costs for insurance companies and businesses. To address this challenge, insurance companies are focusing on developing new risk management strategies and offering new products such as flood insurance. However, the article argues that effective and feasible coordination shortens recovery time and can therefore drastically reduce the financial costs of a crisis—that is, the insurance costs. The paper analyses the deficit in crisis management during heavy rain events in Germany, based on the 2021 Ahr valley flood. The analysis is conducted based on document analysis and interviews and focuses on three areas of deficit: coordination between crisis staffs and (1) civil society, (2) emergency responders, and (3) political leaders. The paper highlights the importance of coordination during a crisis, which can help to address the crisis more efficiently and effectively, minimise damage and get communities back on their feet faster. The paper recommends policy changes to improve interface management and disaster management coordination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In its latest report 2023, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has forecasted an increase in heavy rainfall events as a result of environmental crisis, including global warming and climate change. This increase in heavy rainfall can lead to significant economic costs, particularly for insurance companies due to significant damage to properties. In addition, environmental crises can also impact businesses and individuals, resulting in lost income and increased costs. Insurance companies have responded to this by increasing their premiums and deductibles, as well as by offering new products such as flood insurance. If extreme weather events continue to become more frequent and severe as forecasted by the IPCC, insurance companies are likely to face increasing pressure to provide coverage and manage risks effectively. To meet this challenge, insurers are focusing on developing new risk management strategies. However, they are not focusing on cost avoidance through better coordination of crisis and catastrophe management. While products like parametric insurance ensure fast financial support for individuals which benefits the insured population in case of an event and supports rebuilding efforts, but it does not contribute to disaster prevention. It should be emphasized that this is a good measure for providing prompt assistance, with distribution responsibilities lying with insurers rather than the government. Hence it needs to be discussed, what actions state actors must take for rapid recovery.

The article highlights the potential for improvements in crisis management during heavy rain events, which can lead to cost avoidance for insurance companies. The question is asked what deficits there are in crisis management in Germany and how this could be improved. The analysis is carried out on the basis of the 2021 Ahr valley flood in Germany. It is based on document analysis and interviews with staff with members and task forces, (interim) reports from the task force preparation of the aid organisations, fire brigades and state governments, as well as newspaper articles about the operations in the flood areas. Documents are quoted directly in the text. The interviews have been anonymised and are marked with the date.

To this end, the analytical framework is first developed. This is followed by an analysis of crisis coordination in the Ahr steel floods of 2021. Building on the deficit analysis, possibilities for better coordination are developed in the three areas of (1) the interface management between crisis staffs and civil society (2) the coordination of staffs with emergency responders (3) the role of political leaders.

2 Analytical framework

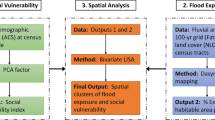

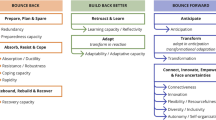

During a crisis, whether a natural disaster, pandemic, or financial crisis, there can be a lot of chaos and confusion (Kaufmann 2020). When working together during a crisis, different organisations, agencies, and stakeholders must share information, resources, and expertise, which can help to address the crisis more efficiently and effectively. This includes coordinating with stakeholders who can help to allocate resources and address critical needs to minimise damage and get communities back on their feet faster. Coordination helps minimise the crisis' negative impact on individuals, communities and economies. It reduces the misallocation of resources and the duplication of efforts (Knodt and Platzer 2023). This can prevent further damage and loss of life, and also help to speed up the recovery phase, allowing affected communities and businesses to recover more quickly from the crisis and build resilience (Fig. 1). It is also essential for reducing the overall impact of the crisis and shortening the recovery period. A shorter recovery time can also lead to a quicker return to normal economic activity and revenue generation, which can have a positive impact on insurance companies (Cavallo and Noy 2009: 7).

Insurance companies consider the risk of potential losses when setting insurance premiums, and the length of time it takes to recover from a crisis can have an impact on that risk assessment. If a crisis is short-lived and the recovery is relatively rapid, the overall financial impact of the crisis may be lower, which could result in lower insurance premiums. This will allow insurers to adjust premiums accordingly, as the risk of significant losses due to the crisis is reduced (Benali and Feki 2017). However, this approach is closely linked to possible preparedness and prevention measures. These measures strengthen the insured's resilience. Hence the long-term financial costs of the crisis and its adverse economic and social effects can be reduced.

The paper analyses the significance of a well-developed and organised interface management during the response and coping phase and points out current weaknesses. On the basis of various (interim) reports, a participant observation during the event and expert interviews in its aftermath a deficit analysis was conducted. We primarily focus on coordination processes between the crisis staff and three actors: civil society, emergency responders, and political leaders (Fig. 2). In the first dimension, the crisis staff needs to coordinate all actions taken by the civil society especially spontaneous helpers. These self-organised citizens are increasingly important in disasters, as they provide essential psychological support and coordinated clean-up efforts. Often, they take on tasks which are not handled by emergency responders. However, a lack of coordination between professional crisis management systems and spontaneous responders can potentially resulting in a parallel structure alongside the professional system. Furthermore, the crisis staff is responsible for coordinating all measures taken by emergency responders. The forces are depended on the priority settings and leadership of the staff for a holistic emergency management while working with limited resources. In the third dimension the staff needs to coordinate with political leaders, since they are responsible for the implementation for and decide on necessary measures. Together, these key players in disaster management ensure that the event can be overcome, if they work hand in hand. With the conducted research we were able to identify several challenges which occurred during the response and coping phase and multiple shortcomings in disaster management coordination are evident. Deficiencies are visible in every dimension of coordination. Based on this analysis, recommendations for policy changes to improve interface management are provided. These deficiencies are neither new nor event-specific. Therefore, they are best interpreted as symptoms of an overdue update of command and control organization and preparedness. The following deficit analysis traces the challenges during the flood situation based on difficulties in response and situation management.

3 Crisis coordination and the floods in the Ahr valley 2021

In the summer of 2021, the low-pressure system "Bernd" brought heavy rain from 12 to 15 July, leading to significant flooding. Local monitoring stations recorded record levels in many regions (Manandhar et al. 2023). The heavy rainfall and its devastating consequences have hit the German federal states of Rhineland-Palatinate and North Rhine-Westphalia in Germany very hard. The event itself was coupled with deficiencies in the early warning systems, resulting in a lack of public information and inadequate evacuation measures (Apel et al. 2022; Thieken et al. 2022). One of the most severely affected regions in Germany was a part of the Ahr valley in the state of North Rhine-Westphalia. Here, the event resulted in around 140 deaths, countless injuries and immense personal and material losses for many residents of the affected regions. Several factors complicated crisis management during the response phase. The flooding affected multiple towns and villages, destroying homes and buildings, blocking roads and railways, and disrupting essential services such as electricity, telecommunication and water supply (Fekete and Sandholz 2021; Manandhar et al. 2023). In addition, the Ahr valley region is characterised by steep hills and narrow valleys, which intensified the impact of the heavy rainfall and made it hard for emergency response teams to access some of the worst-affected areas (Dietze et al. 2022). This made it difficult to get people and supplies to the affected areas, as did the widespread destruction of infrastructure, including roads and bridges. Rescuers had to use helicopters or boats to reach stranded residents in some cases. Infrastructure such as radio towers, power cable and cable distribution boxes were buried under mud and unusable. Subsequently, there was disruption to communications networks, making it difficult for emergency response teams to coordinate their efforts effectively. Overall, the floods in the Ahr valley were a major challenge for the emergency services, requiring extensive coordination, resources, and resilience to manage the disaster and provide assistance to the victims.

In Germany's federal system, managing disasters of this magnitude is the responsibility of the states (Länder) at the regional level. They generally follow a similar structure and approach, although each country has its own crisis management system. Crisis management involves a number of different actors, such as the police, fire brigade, emergency medical services and civil protection organisations. In this context, the state governments work in close co-operation with the local authorities that operate at the lowest level of disaster management. The aim of crisis management is the effective response to emergencies and disasters, the protection of citizens and infrastructure, and the minimisation of damage and loss. A crisis management system and a crisis committee or task force (known as the crisis staff) are activated in the event of a crisis. It is responsible for planning and implementing measures in the event of a disaster within the territory. This may include the establishment of evacuation zones, the provision of emergency accommodation and the co-ordination of rescue operations. The authorities may issue warnings or instructions. One of the key roles of the local crisis management system is to provide information to the public and advice on how to respond to the crisis. These may include evacuation orders or advice on how to protect yourself from the effects of the crisis.

In general, crisis management in Germany follows a structured and coordinated approach, with clear responsibilities and procedures defined in advance. In an event such as the heavy rain, a crisis team will take the lead in managing the situation based on the fire department service regulation (Feuerwehr Dienstvorschrift 100, short: FwDV 100). The FwDV 100 is a set of guidelines for the operational management of firefighting units in Germany. It provides a standardised framework for firefighting operations, covering all aspects of organisational and operational structure, role definition and the basis for overall cooperation and coordination. The guidelines are intended to ensure that firefighting operations are conducted safely, effectively and efficiently, and are consistent across different regions and fire departments in Germany. Today the FwDV 100 is a general guideline for all emergency response forces in crisis management such as the German Federal Agency for Technical Relief (Technische Hilfswerk (THW)) or civil relief organisations (like the German Red Cross, Johanniter-Unfall-Hilfe, Malteser Hilfsdienst, and Arbeiter-Samariter-Bund).

The THW and civil relief organisations are the backbone of the national emergency response, along with fire departments, police, and the Armed Forces. The THW on the one hand is responsible for providing technical assistance in emergency situations (THW 2023). The civil relief organisations on the other hand are responsible for a wide range of emergency medical services. They provide emergency medical services in the event of a crisis. They give medical assistance to those injured in disasters and transport them to hospitals for further treatment as well as on-site psychological support. They can also organise logistics and distribution services, including providing food, water, and shelter to affected populations during emergencies. In the event of a disaster, such as the heavy rainfall 2021, all civil protection actors are in action and must work closely together for the implementation of the necessary measures. In addition to these organised responders, citizens are extremely important participants. They contribute by helping to manage crises.

The coordination of these actors involved in crisis management is more dimensional (Fig. 2). This is illustrated by the heavy rainfall event in the Ahr valley in July 2021. During the initial response the local level was responsible for disaster management. Local firefighting teams, civil relief organisations, and the THW immediately began responding. County administrative and the crisis staff began coordinating efforts and attempted to coordinate with political leaders. At the request of the local government, the Supervisory and Service Directorate (Aufsichts- und Dienstleistungsdirektion (ADD)) assumed responsibility in the days following the rain. The crisis staff set up by the ADD began to operate and took over from local teams. Outside of an incident, the ADD has municipal supervision over the counties. Rescuers from all over Germany and neighbouring European countries gathered in the affected areas. Local forces and civilians who acted as spontaneous helpers were added to this. As a result, the event shows, how multiple stakeholders get involved in the management of the situation as soon as it occurs. The crisis staff will be in charge of the coordination of the response efforts of the emergency services and sometimes of civil society. They take the necessary operational-tactical and administrative measures. To ensure the best possible response to the situation at hand, the authorities are constantly coordinating and adjusting their actions. Crisis staff personnel not only need to coordinate with those who are politically responsible for the situation. In addition, central to the implementation of operational emergency response is coordination with emergency responders and commanders, as well as with the civil society.

Even with this system and the guidelines in place, this state crisis management faces various difficulties, dependent on the four phases of the crisis. After an incident follows the direct response by emergency responders and effected citizens. It is characterised by seeming chaotic. The main task for any force during this phase is to improve their situation awareness, collect information about the event and initiate interfaces for coordination. The response phase is followed by the coping phase. During this time structures and cooperation have start to form and work well. Actors like the crisis staff will start to manage and coordinate all measures to overcome the situation. By the time most initial challenges, like missing information and infrastructure, are surpassed the recovery phase starts. It is then, when the effected economy can restart and all necessary functions like infrastructure services are available and reliable again. The restart is followed by the prevention and hardening phase. Characterised by a reflection process prevention and preparedness measures are developed and implemented to improve the resilience towards future events. Deficits in incident management are particularly evident in the first two of four phases of a crisis, the response and recovery phases. Effective coordination is essential to the management of such crisis events. By reflecting on the lessons learned from these phases, a continuous improvement process should take place. This is part of the prevention and hardening phase. It is the base for a better preparedness for future events. In practice we can see, that learning and change processes are often not undertaken in the long term. In the course of any reflection on past events, problems of the crisis management often come to the surface. Improving the system requires not only reflecting on what has been learned but acting and considering changing policies. However, the basic structures of management and coordination in the event of a crisis or loss have changed only marginally in Germany in recent decades.

4 Coordination during the 2021 summer floods

In Germany, the 2021 summer floods have put the debate about disaster management and its consequences on the agenda. As we will show, the event underscored profound challenges in how crisis staffs coordinate with civilians, emergency responders, and political leaders in Germany. The evident deficits during the response and coping phase of the crisis show the potential for resilience building. Furthermore, a better and more efficient management during this phase leads to a faster recovery phase. Ultimately reducing not only the economic impact of such events but also the potential insurance costs of a crisis.

4.1 Coordination between crisis staffs and civil society

Civil society, especially in the form of spontaneous citizen self-organisation, plays an increasingly important role in disasters. Volunteers provide essential psychological support to citizens affected by disasters, in addition to coordinated clean-up efforts. In the immediate aftermath of the disaster 2021, spontaneous volunteers travelled to the crisis areas and continued to work for weeks after the event (Helfer-Stab Ahrtal 2021). They coordinated themselves via social media (e.g. the homepage "AHRhelp"), networks or on the spot. They build up their own infrastructure including deployment plans, equipment management and a shuttle service. This establishes a parallel structure alongside professional crisis management system. Professional management of an interface between the emergency responders and spontaneous responders is lacking. In addition, spontaneous helpers are usually not trained for crisis areas and cases. For ad-hoc and short-term volunteers, this is a particular problem. There is a lack of prescribed structures (procedures, documentation, etc.) or behaviour in special situations (medical assistance, confrontation with deaths, trauma, etc.). Spontaneous responders are thus not prepared for these specific situations and do not receive support.

Utilising the help of spontaneous helpers, means to plan for their involvement in the professional and structured management of the crisis from the very beginning. Existing crisis management systems in Germany, however, are still not sufficiently prepared for the coordination with spontaneous responders. As seen in 2021, a lack of coordination can lead to a logjam of volunteer and professional disaster responders. During the direct response and coping phases, crisis staff did not provide regular and adequate information spontaneous responders as well as to the affected populations. The lack of interface management between crisis staff and civil society is due the absence of an institutionalised access point, permanent available contact persons in the staff and to a lack of a common basis for communication. Another obstacle is the very different communication cultures of the two parties. While government agencies predominantly rely on formal communication structures, societal actors mainly use digital platforms and social networks.

In recent years, crisis managers have recognised the growing importance of communicating with civil society in crisis situations. Information sharing in crisis communication from authorities to citizens via digital channels has increased, especially in preparation for crises. However, the communication does not meet the criteria of exchange. It is mostly used unidirectional from the authorities to the citizens. In the area of crisis preparedness, it is limited to a few information events and brochures that can be downloaded from websites (by the Federal Office of Civil Protection and Disaster Assistance in Germany, among others). When a crisis occurs, both in the response and in the coping phase, there is little or no communication from the state to society beyond the notification of danger. For example, in terms of communication, in July 2021, civil society was not integrated into the crisis staffs' situational awareness. As a result, spontaneous helpers in particular developed their own situation reports, derived priorities, and worked on them independently of the staff. In the course of the response, volunteers in the Ahr Valley formed staff-like structures. This allowed for coordinated processes and created interfaces with the crisis staff structures (Helfer-Stab Ahrtal 2021) that were not used by the crisis staff. It is important to note, that it was not until nearly a week had passed that disaster management and administrative personnel of the crisis staff initiated key process education and linkage interfaces for situations such as body discovery, disease threat, etc. (expert interview on 05/08/2021). Thus, although there is a shortage of human resources in disaster management, the resources of self-organised spontaneous helpers are hardly used effectively.

The analysis has shown that there are significant deficiencies in interface management and that new strategies and policies for an effective proactive and reactive interface management are needed. Federal and state decision-makers should work together with civil society to develop a proactive interface management. There is a need for guidelines for cooperation between emergency responders, crisis staff and the public/spontaneous helpers in the event of a crisis. The following questions should be answered when setting up interface management: What are the best tasks for spontaneous helpers to take on?; What expertise and resources can be tapped into? and How can volunteer forces best be focused, coordinated or communicated with?. It is necessary to give further explanations and information on possible fields of action and responsibilities for spontaneous helpers, elaborations on requirements and behaviour in crisis areas (equipment, health risks, communication channels, etc.), and training opportunities for civil relief organisations and helpers. Such elaborations should be taken into account in practical implementation, applied and integrated into local plans together with civil society.

During a crisis, communication and coordination between volunteers and crisis staff must be reviewed to ensure that civilians are adequately involved in the management of the situation in an appropriate manner, in order to realise the full potential of civil society's important contributions to crisis management. The civil society is a resource to be embraced, as spontaneous helpers are often faster and less complicated than institutionalised organizations. Centralised management in the form of a single point of contact (SPOC) would be one solution. The SPOC is designed as a standing interface between staffs and civil society for the response and coping phase. It is necessary to include spontaneous responders or representatives in joint situation meetings to make the exchange of situation reports with the disaster and administrative personnal within the crisis staff possible. This will require an adaptation of the staff regulations and training concepts. In this sense, the command levels according to the FwDV 100 must be supplemented, for example, by a civilian component, which requires a single point of contact with the staff.

4.2 Coordination between staff and emergency responders

Effective communication between the staff and the emergency responders on site is crucial for efficient management of a disaster. It is difficult to navigate and direct forces if this interface fails. During the July 2021 disaster, the crisis management was faced with a large-scale and permanent failure of infrastructure (especially concerning telecommunication), which prevented communication through established reporting channels. The destruction of masts, for example, made the use of digital radio impossible for a time. As a result, communications with the emergency responders were disrupted, sometimes for days at a time. This resulted in organisational problems between the crisis staff and emergency responders.

The temporary breakdown in communicating led to alternative structures for communicating forming. Personally known emergency responders were involved through short communication paths (expert interview on 05/08/2021). They replaced established hierarchical reporting channels in the disaster management system. Managerial staff was not always notified, and assignments given were duplicated or not carried out at all. For a long time, the lack of visibility into available forces and responsibilities exacerbated these problems (expert interview on 20/07/2021). Effective operational planning by the staffs was hampered—as a result, forces often spent more time on standby than in action. For example, emergency responders from Schleswig–Holstein who—although urgently needed—spent several days on standby outside the area of operation without being deployed, as reported by German television (Report Mainz, August 3, 2021).

Moreover, such large-scale crisis requires different command structures than local and temporary operations. The term "rear command and control" is in use here. In other words, operational and tactical decisions and orders are not made on site, but rather centrally by the crisis staff. A centralised structure is necessary because it gives the crisis staff an overview of the overall situation and possible interdependencies within the multi-dimensional and complex situation. This leads to longer communication and information paths, and decision-making processes are spread over several levels. For emergency responders, decisions thus take longer and are not always transparent. This scenario of rear command and control through staff structures was new for many emergency responders during the floods in the Ahr Valley. After all, an actual disaster control operation for the emergency responders was comparatively rare. To some extent, their awareness of this type of command and control was lacking, as was their confidence in the cooperation with the staffs.

During the 2021 crisis, the emergency response community struggled with communication technology failures that impacted coordination between staffs and responders raised fundamental challenges in terms of knowledge about leadership in large-scale disaster operations and trust. As a result, better and more intensive preparation of responders for disaster response is needed. This should be planned and implemented by the local (volunteer) fire departments and the local groups of the civil relief organisations during the training of emergency responders. There is a need for knowledge transfer on the specifics of rear command and control in major emergencies. This should already be planned and implemented by local (voluntary) fire departments and the local groups of the civil relief organisations during the training of emergency responders. A transfer of knowledge regarding the specifics of command and control in major emergencies, and the roles and limitations of the structures involved, is needed. This creates transparency into the processes and issues in operational situations. After all, an actual disaster control operation is comparatively rare for the emergency responders. Furthermore, an overarching culture of error must be created. This can facilitate a continuous improvement process and embedding lessons learned into the routines. Here, education must go hand in hand with practical training.

4.3 Coordination between staffs and political leaders

In Germany, leadership in disaster situations and major emergencies consists of an operational, administrative (both represented in the crisis staff) and political components. Each has their specific area of responsibility. At the top is a political authority with overall responsibility (e.g. mayors or county counsel). They decide on and are responsible for the measures to be implemented by the crisis staff. As shown earlier, the counties and district commissioners are mainly in charge. The local level is usually directed by the commissioner during an event. However, due to the lack of communication infrastructure, among other things, mayors became responsible for crisis management. In addition, since the heavy rainfall event affected the entire state, responsibility and decision-making authority had to be assumed by the prime minister in charge of the respective sectors, such as transport, labour or social affairs. During the crisis management it was observable, that these higher levels, either did not assume their foreseen responsibility and decision-making authority or did so only inadequately. In the process, required high-impact decisions (such as evacuations or the declaration of a disaster situation) were not made. Probably the most prominent example is the supposed transfer of responsibility from the county counsel in Ahrweiler to the local head of the disaster control authority. Rather than focusing on the personal performance of political leaders, however, this article seeks to address structural deficits in the role of political leaders.

Political leaders are responsible for overall coordination, initiating action, and making key decisions. Crisis staffs then work through these decisions and measures. Considering the role of the political decision-makers in the flood disaster, one might ask whether there was an awareness and acceptance of this responsibility and the need for courageous decisions existed. One problem is that those with overall political responsibility are not required to participate in exercises and training courses on disaster prevention and crisis management. As a result, there may be a lack of awareness of the working methods and structures in place for disasters and large-scale emergencies. At the same time, there seems to be a lack of awareness of the need for political accountability for key courageous decisions. Political willingness to take risky and difficult decisions is further hampered by enormous pressure to act and a lack of information. The analysis has shown that those with overall political responsibility at the various levels have partially withdrawn from the field of responsibility for disaster management and have not fulfilled the role assigned to them. The necessary courageous decisions (such as evacuations or the declaration of a state of disaster) have not been taken.

The recommendation in this area is to improve the involvement of political leaders in civil protection exercises and thus practicing the necessary role. Without active participation, the knowledge of the structures and the interest in the complexity of the situation cannot be generated by political leaders. Coordinating the actions of administrative and disaster management personnel within the crisis staff cannot close this responsibility gap. Policy changes are necessary to build a frame which make it mandatory for political leaders to be trained in disaster management and in their responsibilities in the event of a disaster. A major problem here is the widespread absence of a culture of error. Disaster management is about making quick decisions based on all available information. In retrospect, with more knowledge about the situation, these could be described as poor. However, the focus of post-mission evaluation is not on normative assessment, but on processing the consequences of decisions in the form of learning processes for the future. For those with political responsibility, however, it is precisely the normative evaluation that proves to be particularly important. For fear of the consequences in the form of a future loss of votes, acute problems in the management of the situation between staff and political leaders may not be made transparent by those involved. Active participation in exercises is just as important as the implementation of an appropriate error culture (Table 1).

5 Conclusion

At present, there is increasing discussion about the potential for improvement in German civil protection and disaster management. This "window of opportunity" is needed to implement necessary policy changes. These need to highlight the importance of coordination to minimise the negative impact of crises on individuals, communities, and economies, reducing the misallocation of resources and duplication of efforts, and shortening the recovery period. Enabling a more effective and faster crisis management hence leads to cost avoidance and a better outcome for insurance companies.

Any system, process, or activity will always involve some degree of risk or uncertainty. It is impossible to completely eliminate all possible threats or vulnerabilities, even with the most sophisticated security measures and procedures. Highly effective crisis management can therefore enable a society to recover from an event and limit its consequences. At the outset, the paper showed, that when a crisis occurs, insurance companies are likely to receive a high volume of claims, which can be costly to process and pay out. A short recovery time of a crisis can help to reduce the costs of insurance companies by reducing the volume and severity of claims, reducing the likelihood of subsequent losses or damages, and promoting a quicker return to normal economic activity. Better coordination during the response and recovery phases will facilitate this. Lessons learned from the heavy rainfall event in the summer of 2021 show that strengthening the coordination of all actors is extremely relevant for coping with such a disaster. The floods highlighted the need for better coordination and cooperation between the three dimensions.

Furthermore, coordination problems, such as those in the Ahr valley, can have a negative impact on insurance costs. The policy changes outlined above are therefore necessary to reduce these impacts. This includes developing clearer roles and responsibilities, sharing information and resources, and building trust between stakeholders. Better coordination among stakeholders and greater involvement of civil society, as outlined in our recommendations, would improve disaster management, and increase preparedness for future disasters and crises. The first steps toward increased resilience can be based on the recommendations developed and presented.

References

Apel H, Vorogushyn S, Merz B (2022) Brief communication: Impact forecasting could substantially improve the emergency management of deadly floods: case study July 2021 floods in Germany. Nat Hazard 22(9):3005–3014. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-22-3005-2022

Cavallo EA, Noy I (2009) The economics of natural disasters: a survey. SSRN J. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1817217

Helfer-Stab Ahrtal (2021.): Wir über uns. https://helfer-stab.de/ueber-uns/. Accessed 15 December 2022

Knodt; M.; Platzer, E. (2023): Lessons Learned: Koordination im Katastrophenmanagement. Policy Paper. Darmstadt.

Manandhar B, Cui S, Wang L, Shrestha S (2023) Post-flood resilience assessment of july 2021 flood in Western Germany and Henan. China Land 12(3):625. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12030625

Report Mainz (03.08.2021). https://www.ardmediathek.de/video/report-mainz/report-mainz-vom-3-august-2021/das-erste/Y3JpZDovL3N3ci5kZS9hZXgvbzE1MDc2MTI Accessed 15 December 2021.

Thieken, Annegret H.; Bubeck, P.; Heidenreich, A.; Keyserlingk, J. von; Dillenardt, L.; Otto, A. (2022): Performance of the flood warning system in Germany in July 2021 – insights from affected residents. EGUsphere:973–990. https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-2022-244.

THW (2023): The THW. https://www.thw.de/EN/THW/thw_node.html, Accessed 22 March 2023.

von Kaufmann F (2020) Die Überwindung der Chaosphase bei Spontanlagen. Der Transformationsprozess von der Allgemeinen Aufbauorganisation in die Besondere Aufbauorganisation am Beispiel der Branddirektion München. In: Kern E-M, Richter G, Müller JC, Voß F-H (eds) Einsatzorganisationen. Springer Fachmedien, Wiesbaden, pp 249–263

Acknowledgements

This work has been funded by the LOEWE initiative (Hesse, Germany) within the emergenCITY center.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Platzer, E.K., Knodt, M. Resilience beyond insurance: coordination in crisis governance. Environ Syst Decis 43, 569–576 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10669-023-09938-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10669-023-09938-7