Abstract

Smoking seems modestly associated with breast cancer, but the potential dual effect of smoking (with opposing properties: carcinogenic vs anti-estrogenic) is understudied. The relationship between smoking before and after menopause and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer was investigated in the Netherlands Cohort Study (NLCS). In the NLCS, 62,573 women aged 55–69 years provided information on smoking, dietary and other lifestyle habits in 1986. Follow-up for cancer incidence until 2007 (20.3 years) consisted of record linkages with the Netherlands Cancer Registry and the Dutch Pathology Registry PALGA. Multivariate case-cohort analyses were based on 2526 incident breast cancer cases and 1816 subcohort members with complete data on smoking. When smoking during pre- and postmenopausal periods was mutually adjusted for, breast cancer risk was significantly positively associated with premenopausal smoking pack-years, but inversely associated with postmenopausal smoking pack-years, both in a dose-dependent manner. In continuous analyses, the hazard ratios (95% CI) were 1.35 (1.10–1.65), and 0.47 (0.28–0.80) per increment of 20 premenopausal, and postmenopausal pack-years, respectively. The interaction between pre- and postmenopausal pack-years in relation to breast cancer risk was significant (P < 0.001). This study highlights the importance of distinguishing and adjusting for smoking in different life periods, and suggests dual effects of smoking on postmenopausal breast cancer risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The association between smoking and breast cancer remains controversial. A recent meta-analysis [1] found a modest positive association, which was not dependent on including/excluding passive smokers from the reference group. Associations were stronger positive when smoking started early [1], particularly before first birth (e.g. [2, 3]).

However, smoking has carcinogenic properties—through polycyclic hydrocarbons, nitrosamines, and aromatic amines-, and anti-estrogenic properties [4], through inhibiting estrogen production or changing estrogen metabolism [5]. The dual effect of these opposing properties on breast cancer risk is understudied. Only two prospective studies have investigated mutually adjusted effects of smoking pack-years before and after menopause [2, 6]. Due to lower endogenous estrogen production, the anti-estrogenic effect of smoking may become more apparent after menopause and possibly affecting postmenopausal breast cancer risk. This hypothesis was investigated in the Netherlands Cohort Study (NLCS).

Methods

Study population and follow-up

The Netherlands Cohort Study (NLCS) started in September 1986 and the female part included 62,573 women aged 55–69 years [7]. At baseline, participants completed a mailed, self-administered 11-page questionnaire on diet, smoking habits, anthropometry, reproductive history, physical activity and other cancer risk factors. The NLCS was approved by institutional review boards from Maastricht University and TNO (Netherlands Organization for Applied Scientific Research). All cohort members consented to participation by completing the questionnaire. Data were processed and analysed using the case-cohort approach, enumerating the cases for the entire cohort, and estimating the person-years at risk in the cohort from a subcohort. This subcohort of 2589 women was randomly sampled from the cohort immediately after baseline and is being followed up for vital status. Follow-up for cancer incidence was established by annual record linkage with the Netherlands Cancer Registry and PALGA, the nationwide Dutch Pathology Registry. After 20.3 years of follow-up, a total of 3354 incident female breast cancer cases were detected. Cases and subcohort members were excluded if they reported a history of cancer (except skin cancer) at baseline and if their smoking data (pack-year level) were incomplete; the selection and exclusion steps are shown in Fig. S1 (supplementary data). There were no relevant differences between included and excluded subjects (data not shown). There were 1816 subcohort members and 2526 breast cancer cases available for multivariable analysis.

Exposure assessment

Tobacco smoking was addressed through questions on baseline smoking status, and the ages at first exposure and last (if stopped) exposure to smoking, smoking frequency, and smoking duration, for cigarette, cigar, and pipe smokers. Pack-years of smoking were calculated by multiplying the total years of cigarette smoking by the number of cigarettes smoked per day divided by 20. Passive smoking questions related to smoking habits of parents and spouses, exposure to passive smoking at work (past or present), and duration of current daily exposure to passive smoking (open ended question; private and occupational settings combined).

Statistical analysis

The relationship between smoking and breast cancer risk was evaluated using cox proportional hazards models. Standard errors were estimated using the robust Hubert–White sandwich estimator to account for additional variance introduced by the subcohort sampling [8]. Active cigarette smoking was analyzed as smoking status at baseline (never smokers, ex, current; ever smokers), intensity, duration and pack-years of smoking, age at smoking initiation relative to menarche and first birth, age at cessation and years since cessation for ex-smokers. Trend tests were conducted by fitting ordinal exposure variables as continuous terms, after exclusion of never smokers. Since 98% of never active smokers were exposed to passive smoking by parents, spouse, or at work, it was impossible to exclude passive smokers from the reference category. Estimated pack-years of smoking in different life periods (e.g., before and after menopause) were derived from age at initiation, age at stopping or baseline age, age at menopause, by dividing the total pack-years proportionally over these periods according to duration. In multivariable analyses, hazard ratios (HRs) were corrected for potential confounding by age at baseline (55–59, 60–64, 65–69 years), body height (continuous, cm), BMI (<18.5, 18.5–<25, 25–<30, ≥30 kg/m2), non-occupational physical activity (≤30, >30–60, >60–90, >90 min/day), highest level of education (primary school or lower vocational, secondary or medium vocational, and higher vocational or university), family history of breast cancer in mother or sisters (no, yes), history of benign breast disease (no, yes), age at menarche (≤12, 13–14, 15–16, ≥17 years), parity (nulliparous, 1–2, ≥3 children), age at first birth (<25, ≥25 years), oral contraceptive use (never, ever), postmenopausal HRT (never, ever), current smoking status at baseline (no, yes), passive smoking status at work, at home and parental, nutritional supplement use (no, yes), and alcohol intake (0, 0.1–<5, 5–<15, 15–<30, ≥30 g/day).

No adjustment was made for age at menopause, because smoking can induce earlier onset of menopause [6, 9] and the smoking—breast cancer relationship might be mediated by age at menopause. Analyses were repeated after excluding cancers occurring in the first 2 years of follow-up.

Smoking-breast cancer analyses were also conducted within strata of other risk factors; interactions were tested using Wald tests and cross-product terms. In addition, analyses were performed, comparing hormone receptor subtypes of breast cancer. Analyses were conducted using Stata version 12.

Results

There were 60.7% never, 19.4% ex- and 19.9% current smokers among the subcohort members. Supplementary Table 1S summarizes several baseline characteristics according to smoking status. Ever smokers tended to be younger and leaner than never smokers, while alcohol consumption, education and OC/HRT use was higher. Mean age at menopause was lower in current smokers than never or ex-smokers. Mean age at smoking cessation was 47.1 years; ex-smokers less often reported familial breast cancer, but benign breast disease was more likely. Only 2.4% of never smokers were not exposed to passive smoking by parents, spouse, or at work; this was even lower for ever smokers.

Although statistically significant associations were seen in age-adjusted analyses, baseline smoking status, daily amount, duration and pack-years were not significantly associated with breast cancer risk in multivariable analyses (Table 1), with a HR for the contrast ever versus never smokers, of 1.14 (95% CI 0.98–1.32). After an initial gradual increase in risk with increasing pack-years, the highest exposure category showed a decreased risk, albeit nonsignificant. Age at starting or age at stopping smoking were not significantly associated with breast cancer risk, without a clear trend. An analysis of starting age relative to age at menarche and age at first birth (following Gaudet et al. [10]) showed that the few women who started smoking before menarche were at increased risk (HR = 16.96, 95% CI 4.11–69.89). For those starting after menarche, there was no clear trend in risk with longer periods between starting and first birth.

When smoking during pre- and postmenopausal periods was mutually adjusted, breast cancer risk was significantly positively associated with premenopausal smoking (P-trend = 0.003), but inversely with postmenopausal smoking pack-years (P-trend = 0.010) (Table 2). In continuous analyses, the HRs (95% CI) were 1.35 (1.10–1.65), and 0.47 (0.28–0.80) per increment of 20 premenopausal, and postmenopausal pack-years, respectively. This inverse relationship with postmenopausal pack-years seemed stronger in never HRT-users and in those with overweight (P-heterogeneity nonsignificant). Further analyses of effect modification by other factors revealed no significant heterogeneity in these associations (data not shown). There was also no significant heterogeneity in these associations, when comparing hormone receptor subtypes of breast cancer, neither was there an effect of exclusion of the first 2 years of follow-up (data not shown).

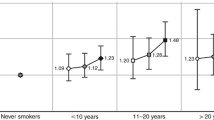

The interaction between pre- and postmenopausal pack-years in relation to breast cancer risk was highly significant (P < 0.001), and is illustrated in Fig. 1, where the HR of breast cancer is presented for various combinations of pre- and postmenopausal pack-years, compared to never smokers. The figure shows that for those who only smoked before menopause, there is an increasing risk with increasing pack-years of smoking: from a HR of 1.07 for 1–10 premenopausal pack-years to 1.82 for 20+ pack-years. However, a decreasing trend in risk is visible with increasing pack-years of postmenopausal smoking. For example, the HR for those with 20+ premenopausal pack-years and 10+ postmenopausal pack-years was 0.99 compared to a HR of 1.82 for women who only smoked before menopause; it was 0.56 for those with 1–10 premenopausal pack-years and 10+ postmenopausal pack-years.

Hazard ratio of breast cancer according to pack-years of premenopausal smoking and pack-years of postmenopausal smoking.

Note Multivariable analyses were adjusted for: age at baseline (55–59, 60–64, 65–69 years), current smoking status (no, yes), body height (continuous, cm), BMI (<18.5, 18.5–<25, 25–<30, ≥30 kg/m2), non-occupational physical activity (≤30, >30–60, >60–90, >90 min/day), highest level of education (primary school or lower vocational, secondary or medium vocational, and higher vocational or university), family history of breast cancer in mother or sisters (no, yes), history of benign breast disease (no, yes), age at menarche (≤12, 13-14, 15–16, ≥17 years), parity (nulliparous, 1–2, ≥3 children), age at first birth (< 25, ≥25 years), oral contraceptive use (never, ever), postmenopausal HRT (never, ever), current smoking status at baseline (no, yes), passive smoking status at work, at home and parental, nutritional supplement use (no, yes), and alcohol intake (0, 0.1–<5, 5–<15, 15–<30, ≥30 g/day)

Discussion

This study showed that pack-years of premenopausal smoking was positively associated, but postmenopausal smoking was inversely related to postmenopausal breast cancer risk, in a dose-dependent manner, when both were taken into account. There was a statistically significant interaction between these factors (antagonism). Baseline smoking status, overall duration and smoking intensity were not significantly related to risk.

A meta-analysis of 27 prospective studies [1] concluded that ever active smoking was modestly, but significantly, associated with breast cancer risk, with no evidence of heterogeneity. The reported SRR of 1.10 is comparable to the HR of 1.14 found here in the NLCS. The meta-analysis reported no differences between subgroups, particularly pre/post-menopause. However, this pre/post-menopause contrast does not refer to the distinction between pre- and postmenopausal smoking, which seems more important [2, 4, 6]. When pack-years smoked in pre- versus postmenopausal periods were mutually adjusted in the NLCS, the opposite associations with breast cancer appeared even stronger than in earlier prospective studies [2, 6], with a significant interaction between pre- and postmenopausal pack-years, suggesting moderately strong opposite effects of smoking: carcinogenic versus anti-estrogenic effects [4]. The Nurses’ Health Study [6] and EPIC [2] were the only two prospective studies that have investigated mutually adjusted effects of smoking pack-years before and after menopause on breast cancer risk.

The anti-estrogenic effect of smoking among postmenopausal women may further reduce their already low circulating estrogen levels [6]. The stronger inverse relationship in women who never used HRT is also compatible with this [2, 6]. In premenopausal years, the anti-estrogenic effect of smoking may not be strong enough to reduce estrogen levels meaningfully, leaving the dominant carcinogenic effect of smoking [4, 6]. The dual effects only appear after mutual adjustment for smoking in different periods, and may explain part of the inconsistencies in the literature on smoking and breast cancer. It might also explain why, in our analysis without mutual adjustment, we observed a decreased breast cancer risk for women exposed to a large number of pack-years (i.e. higher proportion of postmenopausal smoking in the NLCS), while at lower exposure levels a gradual increase in breast cancer risk was seen with increasing pack-years of smoking.

The prospective design and high completeness of follow-up of the NLCS make information bias and selection bias unlikely. In other cohort studies, a further distinction was made between pack-years smoked before and after first birth, and a stronger positive association with the former was found [2, 6]. The NLCS-data did not allow this distinction. However, women who started smoking before first birth, were at increased risk as opposed to those who started after first birth. A further limitation was that there was no update of smoking information after baseline, and that exclusion of passive smokers from never active smokers was impossible, because almost all women had been passively exposed. Nevertheless, we found generally stronger associations than others who did exclude passive smokers (e.g. [2], and the importance of exclusion is not clearly demonstrated in meta-analysis [1].

Anti-estrogenic effects of smoking have been suggested by an earlier age at natural menopause and reduced endometrial cancer risk [5]. Smoking may exert anti-estrogenic effects through nicotinic alkaloids inhibiting aromatase activity and aromatization of androgens into estrogens, the major source of postmenopausal endogenous estrogen production [5], and increased hepatic estrogen clearance [9]. There is evidence that smoking inactivates inactivates estrone, the most important estrogen in the postmenopausal phase. However, there may also be increased formation of genotoxic estrogen metabolites, the (semi)quinones [9]. Given the multiple effects of smoking, further work will be needed to understand the relationships of smoking, estrogen production and metabolism, and carcinogenesis [5].

In conclusion, this study demonstrates the importance of distinguishing and adjusting for smoking in different life periods, and suggests dual effects of smoking on breast cancer, consistent with two other large cohorts [2, 6]. The carcinogenic effect of premenopausal smoking highlights the need for early age prevention programs.

References

Macacu A, Autier P, Boniol M, Boyle P. Active and passive smoking and risk of breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;154(2):213–24. doi:10.1007/s10549-015-3628-4.

Dossus L, Boutron-Ruault MC, Kaaks R, et al. Active and passive cigarette smoking and breast cancer risk: results from the EPIC cohort. Int J Cancer. 2014;134(8):1871–88. doi:10.1002/ijc.28508.

Gram IT, Little MA, Lund E, Braaten T. The fraction of breast cancer attributable to smoking: the Norwegian women and cancer study 1991–2012. Br J Cancer. 2016;115(5):616–23. doi:10.1038/bjc.2016.154.

Band PR, Le ND, Fang R, Deschamps M. Carcinogenic and endocrine disrupting effects of cigarette smoke and risk of breast cancer. Lancet. 2002;360(9339):1044–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11140-8.

Gu F, Caporaso NE, Schairer C, et al. Urinary concentrations of estrogens and estrogen metabolites and smoking in caucasian women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2013;22(1):58–68. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0909.

Xue F, Willett WC, Rosner BA, Hankinson SE, Michels KB. Cigarette smoking and the incidence of breast cancer. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(2):125–33. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.503.

van den Brandt PA, Goldbohm RA, van ‘t Veer P, Volovics A, Hermus RJ, Sturmans F. A large-scale prospective cohort study on diet and cancer in The Netherlands. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43(3):285–95.

Lin D, Wei L. The robust inference for the cox proportional hazards model. J Am Stat Assoc. 1989;84(408):1074–8.

Ruan X, Mueck AO. Impact of smoking on estrogenic efficacy. Climacteric J Int Menop Soc. 2015;18(1):38–46. doi:10.3109/13697137.2014.929106.

Gaudet MM, Gapstur SM, Sun J, Diver WR, Hannan LM, Thun MJ. Active smoking and breast cancer risk: original cohort data and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(8):515–25. doi:10.1093/jnci/djt023.

Acknowledgements

I thank the participants of this study and the Netherlands Cancer Registry and Dutch Pathology Registry PALGA for providing data, and I thank the staff and students of the Netherlands Cohort Study for their valuable contributions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There are no competing financial interests in relation to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

van den Brandt, P.A. A possible dual effect of cigarette smoking on the risk of postmenopausal breast cancer. Eur J Epidemiol 32, 683–690 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-017-0282-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-017-0282-7