Abstract

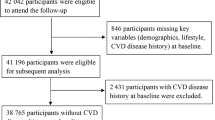

Month of birth—a proxy for a variety of prenatal and early postnatal exposures including nutritional status, ambient temperature and infections—has been linked to mortality risk in adult life. We assessed the relation between month of birth and cause-specific mortality risk from cardiovascular diseases, infections, tumors and external causes—in ages of more than 50–80 years. In this nation-wide Swedish study, 4,240,338 subjects were followed from 1991 to 2010, using data from population-based health and administrative registries. The relation between month of birth and cause-specific mortality risk was assessed by fitting Cox proportional hazard regression models with attained age as the underlying time scale. In models adjusted for sex and education, month of birth was associated with cardiovascular and infectious mortality, but not with deaths from tumors or external causes. Compared with subjects born in November, a higher cardiovascular mortality was seen in subjects born from January through August, peaking in March/April [hazard ratio (HR) 1.066 compared to November, 95 % CI 1.045–1.086]. The mortality from infections was lowest for the birth months November and December and a distinct peak was observed for September-born (HR 1.108 compared to November, 95 % CI 1.046–1.175). Month of birth is associated with mortality from cardiovascular diseases and infections in ages of more than 50–80 years in Sweden. The mechanisms behind these associations remain to be elucidated.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Gluckman PD, Hanson M. Living with the past: evolution, development, and patterns of disease. Science. 2004;. doi:10.1126/science.1095292.

Rinaudo P, Wang E. Fetal programming and metabolic syndrome. Annu Rev Physiol. 2012;. doi:10.1146/annurev-physiol-020911-153245.

Doblhammer G, Vaupel JW. Lifespan depends on month of birth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;. doi:10.1073/pnas.041431898.

Gavrilov LA, Gavrilova NS. Season of birth and exceptional longevity: comparative study of American centenarians, their siblings, and spouses. J Aging Res. 2011;. doi:10.4061/2011/104616.

Reffelmann T, Ittermann T, Empen K, et al. Is cardiovascular mortality related to the season of birth? Evidence from more than 6 million cardiovascular deaths between 1992 and 2007. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.10.021.

Doblhammer G. The late life legacy of very early life. Demographic research monographs. Heidelberg: Springer; 2004.

Ueda P, Bonamy AKE, Granath F, Cnattingius S. Month of birth and mortality in Sweden: a nation-wide population-based cohort study. PLoS One. 2013;. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0056425.

Ludvigsson JF, Otterblad-Olausson P, Pettersson BU, Ekbom A. The Swedish personal identity number: possibilities and pitfalls in healthcare and medical research. Eur J Epidemiol. 2009;. doi:10.1007/s10654-009-9350-y.

The National Board of Health and Welfare. Translation table ICD10 to ICD9. 2013. http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/klassificeringochkoder/diagnoskoder/konverteringstabeller. Accessed 3 April 2013.

Villar J, Belizan JM. The timing factor in the pathophysiology of the intrauterine growth retardation syndrome. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1982;37:499–506.

Painter RC, Roseboom TJ, Bleker OP. Prenatal exposure to the Dutch famine and disease in later life: an overview. Reprod Toxicol. 2005;. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2005.04.005.

Roseboom TJ. Undernutrition during fetal life and the risk of cardiovascular disease in adulthood. Future Cardiol. 2012;. doi:10.2217/fca.11.86.

Moore SE, Cole TJ, Collinson AC, et al. Prenatal or early postnatal events predict infectious deaths in young adulthood in rural Africa. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28:1088–95.

Moore SE, Cole TJ, Poskitt EME, et al. Season of birth predicts mortality in rural Gambia. Nature. 1997;388:434.

Palmer AC. Nutritionally mediated programming of the developing immune system. Adv Nutr. 2011;. doi:10.3945/an.111.000570.

Jones KDJ, Berkley JA, Warner JO. Perinatal nutrition and immunity to infection. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2010;. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3038.2010.01002.x.

Samet JM, Tager IB, Speizer FE. The relationship between respiratory illness in childhood and chronic air-flow obstruction in adulthood. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;127:508–23.

Colley JR, Douglas JW, Reid DD. Respiratory disease in young adults: influence of early childhood lower respiratory tract illness, social class, air pollution, and smoking. Br Med J. 1973;3:195–8.

Barker DJ, Godfrey KM, Fall C, et al. Relation of birth weight and childhood respiratory infection to adult lung function and death from chronic obstructive airways disease. BMJ (Clin Res Ed). 1991;303:671–5.

Doblhammer G. Commentary: infectious diseases during infancy and mortality in later life. Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32:294–5.

Salib E, Cortina-Borja M. Effect of month of birth on the risk of suicide. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.105.009118.

Sanborn DE, Sanborn CJ. Suicide and months of birth. Psychol Rep. 1974;. doi:10.2466/pr0.1974.34.3.950.

Lester D, Reeve CL, Priebe K. Completed suicide and month of birth. Psychol Rep. 1970;27:210.

Modestin J, Ammann R, Würmle O. Season of birth: comparison of patients with schizophrenia, affective disorders and alcoholism. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1995;91:140–3.

London WP. Alcoholism: theoretical consideration of season of birth and geographic latitude. Alcohol. 1987;4:127–9.

Goldberg AE, Newlin DB. Season of birth and substance abuse: findings from a large national sample. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:774–80.

Bengtsson T, Lindstrom M. Airborne infectious diseases during infancy and mortality in later life in southern Sweden, 1766–1894. Int J Epidemiol. 2003;. doi:10.1093/ije/dyg061.

Bengtsson T, Ohlsson R. Age-specific mortality and short-term changes in the standard of living: Sweden, 1751–1859. Eur J Pop. 1985;1:309–26.

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by the MD-PhD program at Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden (PU) and the Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research (2010-0643) (AKEB).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ueda, P., Edstedt Bonamy, AK., Granath, F. et al. Month of birth and cause-specific mortality between 50 and 80 years: a population-based longitudinal cohort study in Sweden. Eur J Epidemiol 29, 89–94 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-014-9882-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-014-9882-7