Abstract

Was the sharp upturn of life expectancy in the Netherlands partly due to increased health care funding for the elderly? I argue that there is nothing unusual to the increasing life expectancy since the beginning of the twenty-first century, and that there is no observable relationship with changed health care funding whatsoever. What was highly unusual was the rather dramatic lagging of Dutch life expectancy between 1980 and 2000. The reasons of this failure remain clouded in mystery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In this issue of EJE, Mackenbach et al. [1] argue that the sharp upturn of life expectancy in the Netherlands has been caused by effects of increased health care for the elderly, an increase which is “facilitated” by a “relaxation” of budgetary constraints. In clear words: the authors argue that there was not enough money going around in Dutch health care to deliver optimal care. The authors and I agree about increased health care, but we disagree about the impact of “budgetary constraints”. I compared the evolution of life expectancy and of health care budgets of the Netherlands with the rest of Europe (15 EU and EFTA countries, without the smaller ones, the former socialist nations and Greece, that has no data in the human mortality database).

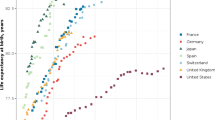

The evolution of life expectancy in the Netherlands is unusual for a Western European country. Being the European champion in 1980 (see Table 1), female life expectancy did not follow the rest of Europe countries for more than 20 years. In 15 EU and EFTA countries, Dutch female life expectancy at age 65 dropped in 20 years from the 1 to the 11 position. The usual suspect, smoking, has been blamed, and was partly responsible. But smoking could never explain the lagging mortality decrease in women aged 65 and older, as smoking was still poorly accepted in these older birth cohorts born before the Second World War [2].

The sharp upturn of life expectancy in the Netherlands, starting around 2002, was remarkable. Mackenbach et al. nicely demonstrate that these sharp changes were caused by strong period effects, occurring in both genders and in all age groups. But in the Table 1, one immediately notices that the Netherlands merely held their position in the second half of the peloton. In an European perspective, there was nothing unusual about the increase of life expectancy between 2000 and 2009. What was unusual was the relative loss of life years in the Netherlands before, in the period 1980–2000: if the Netherlands had maintained its position slightly before France, female life expectancy at age 65 was 2 years higher than it is in 2009.

The authors conclude that the upturn of life expectancy was “facilitated” by increased health care spending. The relation between health care funding and life expectancy has always been tenuous: the US spends per capita twenty times as much than Cuba for the same life expectancy. Chile spends as much as South Africa, for a 27 year higher life expectancy. If that can be blamed to AIDS: Chileans live also 10 years longer than the Russians, who share the life expectancy of … Bangladesh, a poor country that spends 69 international dollar per head per year to health care (www.gapminder.org, accessed 1 December). In 2000, at the end of the “budgetary restrictive period”, the Dutch spent 2,340 USD per capita per year, and was remaining stable in the 7th position. This changed after 2000, when the Netherlands moved up to the third position, spending close to 5,000 USD per capita.

The driver of increasing life expectancy in the European (and many other) elderly is decreased cardiovascular mortality, predominantly caused by health care technology [3]. The authors argue that the period decreases in mortality were seen in a wide variety of causes of death. I don’t think so. The authors show (again beautifully), in webappendix 2, that among women close to 90% of the life expectancy gain (0.88 of 1.07 year) is caused by cardiovascular disease, ill defined conditions and endocrine disorders (webappendix 2). Death from “endocrine” disorders is nearly identical to death from diabetes, often caused by cardiovascular co-morbidity, death from ill defined conditions is often cardiovascular. Among men, the results are similar, taking into account an extra 0.4 year added by decreasing lung cancer and other smoking related mortality. Mortality decreased because of decreasing cardiovascular mortality, as everywhere else. Strict rationing of the highly effective statins before 2002 may have played a role. But in the recent period with upturning life expectancy, the older statins went off patent and became cheap: they cannot explain any budgetary impact.

From an European perspective, trends in life expectancy before 2000 and trends in health care budgets after 2000 show that the Dutch health care system is less efficient than the other European countries. It could not keep up with the other EU countries in life expectancy before 2000. This century, after the introduction of more competition in the Dutch health care system, it did keep up again with European life expectancy but, ironically, at the cost of relatively increasing health care budgets. Success has many fathers, defeat remains an orphan. While politicians and public health scientists claim the success of increasing life expectancy since 2002, the reasons of failure, why life expectancy lagged so severely between 1980 and 2002, has remained clouded in mystery.

References

Mackenbach JP, Slobbe L, Looman CW, van der Heide A, Polder J, Garssen J. Sharp upturn of life expectancy in the Netherlands: effect of more health care for the elderly? Eur J Epidemiol. 2011. doi:10.1007/s10654-011-9633-y

van Bodegom D, Bonneux L, Engelaer FM, Lindenberg J, Meij JJ, Westendorp RG. Dutch life expectancy from an international perspective. Leiden: Leyden Academy on Vitality and Ageing; 2010.

Ford ES, Ajani UA, Croft JB, Critchley JA, Labarthe DR, Kottke TE, et al. Explaining the decrease in U.S. deaths from coronary disease, 1980–2000. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(23):2388–98.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Bonneux, L. Success has many fathers, failure remains an orphan. Eur J Epidemiol 26, 897–898 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-011-9640-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-011-9640-z