Abstract

We describe the rationale for a new study examining the prognostic value of unrequested findings in diagnostic imaging. The deployment of more advanced imaging modalities in routine care means that such findings are being detected with increasing frequency. However, as the prognostic significance of many types of unrequested findings is unknown, the optimal response to such findings remains uncertain and in many cases an overly defensive approach is adopted, to the detriment of patient-care. Additionally, novel and promising image findings that are newly available on many routine scans cannot be used to improve patient care until their prognostic value is properly determined. The PROVIDI study seeks to address these issues using an innovative multi-center case-cohort study design. PROVIDI is to consist of a series of studies investigating specific, selected disease entities and clusters. Computed Tomography images from the participating hospitals are reviewed for unrequested findings. Subsequently, this data is pooled with outcome data from a central population registry. Study populations consist of patients with endpoints relevant to the (group of) disease(s) under study along with a random control sample from the cohort. This innovative design allows PROVIDI to evaluate selected unrequested image findings for their true prognostic value in a series of manageable studies. By incorporating unrequested image findings and outcomes data relevant to patients, truly meaningful conclusions about the prognostic value of unrequested and emerging image findings can be reached and used to improve patient-care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In this article the rationale and methods of the PROgnostic Value of unrequested Information in Diagnostic Imaging (PROVIDI) study are presented. It was designed to investigate the growing amount of unrequested information, identified on diagnostic radiological examinations. PROVIDI’s relatively large study sample and its innovative use of a case-cohort design place it in an ideal position to address some of the more challenging issues pertaining to unrequested radiological findings.

Rationale

Advances in radiological imaging techniques have led to scans of increasingly high resolution and contrast being deployed ever more widely, with the Computed Tomography (CT) [1] and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) [2] modalities leading the way. CT in particular is being deployed for a growing number of clinical indications and over the last decade alone CT image quality has evolved tremendously from single-section helical CT to the greater spatial and temporal resolution offered by multi-detector row CT (MDCT). 4-, 8- and 16-slice scanners are now widely in use, 64- and 256-slice scanners are being introduced into routine clinical practice whilst 320-slice scanners are in late phases of testing [3].

The increasingly widespread use of higher quality CT in routine diagnostic clinical care is causing a corresponding increase in the numbers of unrequested findings being detected, which previously would have gone unnoticed; characterized as unrequested information which is unrelated to the initial scanning indication [4, 5]. As the referrals for routine scanning are typically highly targeted at investigating specific pathologies in specific organs, there is plenty of scope for unrequested findings that are not linked to these initial referrals. These referrals are typically the only additional clinical information that radiologists possess, adding to the uncertainty over how to handle unrequested findings. Evidence from the literature indicates that, on the whole, a large number of unrequested findings are not addressed in routine clinical settings [6], whilst others may be subject to aggressively defensive follow-up [7, 8]. Due to their uncertain clinical significance, such findings pose a novel challenge to radiologists and referring clinicians alike.

Contributing to this trend of increasingly detected unrequested information is the growing culture of medical litigation wherein radiological lawsuits pertaining to missed diagnoses and perceived failure to initiate follow-up investigations form a growing majority of the total [9]. This follow-up exposes patients to potential harm in the form of unnecessary radiation exposure, invasive procedures, the anxiety and stress associated with an uncertain disease-state, as well as financial cost [10].

Additionally, to date the impact of emerging diagnostic findings, such as arterial calcium scores and volumetric analysis of lung nodules [11], are only partially understood and go largely unutilized in routine care. The fact that many potentially predictive findings, as unrequested detected findings, may be available in some form for free on routine scans makes the investigation of their implementation necessary. The potential for risk stratification and preventative treatment for a range of disorders spanning from cardiovascular disease to osteoporosis using unrequested imaging characteritics extracted from the hodgepodge of routine scanning equipment and protocols could be unlocked by demonstrating the prognostic utility of this approach.

The question of how best to adapt to the growing number of unrequested findings has engendered lively debate amongst radiologists, with opinions ranging from advocacy of maximal pursuit for and follow-up of all available findings, to deliberately ignoring anatomical regions and findings beyond the mandates of the scan indication [12–15]. This debate takes place in the context of the limited clinical information typically available to the radiologist and such discussions are a consequence of rapidly advancing techniques with attendant lack of knowledge of their implications. Debate will continue until follow-up studies are performed to investigate which unrequested scan findings are significant and which findings have no clinical impact. For these reasons, there is the urgent need of follow-up studies in routine radiologic settings; there have been but a few admirable attempts [10] at collecting follow-up data on patients with unrequested findings but virtually none investigating the prognostic endpoints. The work carried out in screening settings may not be representative for routine care settings due to for example different hazards for experiencing outcome events and concurrently, there is no basis for comparison between routine-care settings and the radiological prognostic research carried out so far in research settings using screening populations.

The PROVIDI study is the first study that aims to address these issues. It is designed as a longitudinal study, linking unrequested information detected on routine diagnostic Chest CT scans to major health outcomes via national health registries. In doing so we are able to identify those readily accessible unrequested findings that are prognostically relevant and sort them from findings that have little or no value to the patient (Fig. 1). This may allow clinical radiologists to contribute more generally than before to patient care by more effectively utilizing the increasing amount of diagnostic information available, thereby increasing the efficiency of health care.

Methods

Study design

The PROVIDI study is designed as a multi-center retrospective case-cohort study. The cohort consists of subjects with routinely made chest CT scans obtained from eight participating hospitals in the Netherlands (Elkerliek Hospital (Elkerliek), Gelre Hospital (Gelre), St. Antonius Hospital (Antonius), Academic Medical Center Amsterdam (AMC), VU University Medical Center (VUMC), University Medical Center Groningen (UMCG), Academic Hospital Maastricht (AZM), and University Medical Center Utrecht (UMCU)), of which the latter five are tertiary referral centers. A case-cohort design offers significant gains in efficiency over a standard cohort study [16], at the cost of increased complexity in data analysis and the addition of a theoretical layer of assumptions about the uniformity of the cohort. The crucial difference from a normal cohort study is that a random control sample of the cohort is selected at baseline to represent the cohort, making it unnecessary to analyse the whole cohort. Each (cluster of) unrequested finding of interest can then be studied in such an individual sub study that combines the cases that suffered outcome(s) relevant to that finding during follow-up with a new random sample of controls that did not. The control group is to be randomly sampled so that the group is twice as large as the case group for the individual sub study. This permits the use of the PROVIDI cohort in the investigation of the prognostic value of a range of unrelated unrequested findings, as well giving researchers the freedom to pursue unforeseen candidate findings as they emerge. Valid absolute risks, which are indispensable to prognostic research, can be readily calculated.

It was not possible to evaluate the extent of clinical follow-up undergone by patients as a result of unrequested findings with this study design. We did not consider this to be a serious limitation as this is rare in practice [6] and at any rate, it would cause an underestimation of the prognostic effect (as those receiving preventative therapies are probably less likely to experience the outcome of interest).

The PROVIDI study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the University Medical Center Utrecht. The need for written informed consent was waived for all patients due to the retrospective design of this study. A privacy protocol was implemented to ensure that no patient information would be visible whilst reading CT scans and no additional information could be obtained from patient’s medical records and no patient would be contacted as a result of this study.

Study subjects

All patients aged 40 years and older who were referred to one of the participating hospitals with an indication for a chest MDCT between January 2002 and the end of December 2005 were evaluated for inclusion in the PROVIDI study (N = 23.443). Patients with suspected primary lung cancer (including mesothelioma) or distant metastatic disease from other types of cancer (excluding haematological malignancies), 9.077 cases in all, were excluded, on the basis that it is highly unlikely that detection of unrequested imaging findings will alter clinical decision making in patients with such a poor prognosis. This selection was first fully evaluated in a pilot study (Table 1, textbox, pilot study). Consequently, the PROVIDI cohort consists of 14.366 patients, and an equal number of chest CT’s. In cases where patients underwent more than one chest CT examination, only the first CT scan of the series was used for analysis. The chest CT’s were obtained with 2-, 4-, 8-, 16-, 32- or 64-slice scanners of different vendors. All types of chest CT protocols, including contrast and non-contrast scans, were eligible for the PROVIDI study. The CT scans were initially assessed by local hospital radiologists, consistent with routine practice. Subsequently, anonymous copies of all images were stored on disk and transferred to the University Medical Center Utrecht. Patient characteristics and information on type of CT protocol used, including section thickness, tube voltage (kVp), tube load (mAs), and the use of a contrast agent, was abstracted from CT reports by a research physician, who also assessed the CT indication from the CT reports.

Image findings

The specific candidate image findings will differ for each individual study investigating different specific groupings of disease entities and will be selected for their potential prognostic value, as suggested by the available literature and expert opinions from experienced radiologists as well as other clinical specialists and epidemiologists. CT scans will be reviewed, blinded for general scan parameters, CT indication and the outcome status, at a computer workstation, by trained research physicians and supervised by an experienced chest radiologist. Images are to be viewed at standard lung, soft tissue, and bone settings, which are also readily available to radiologists in clinical practice. Reproducibility of image findings will be evaluated and must be sufficient. Some examples of the types of candidate unrequested scan findings are listed in Fig. 2.

Examples of unrequested scan findings. Upper left non-contrast CT image, lower left contrast CT image, upper right CT image in lung setting, lower right contrast CT image in mediastinum setting. a calcifications in Left Main coronary artery and Left Anterior Descending artery, b calcification in descending thoracic Aorta, c: Irregular descending thoracic Aorta with calcification, d diameter of left ventricle, e diameter of heart, f Lung emphysema, g bronchiectasia, h Calcificated plaque in ascending thoracic Aorta, i enlarged lymph node, j Pleural effusion

Endpoints

Main endpoints of the PROVIDI study—established after a first initial linkage—are listed in Table 2. Ideal endpoints would be prevalent diseases in with a major clinical impact and can be treated preventively when diagnosed at an early stage. The endpoints were ascertained through linkage with the National Death Registry and the National Registry of Hospital Discharge Diagnoses for the period January 2002-December 2006. Research showed that the quality of these databases was acceptable [17, 18]. Patients were identified through a combination of a patient’s date of birth, sex, and zip code, using a validated probabilistic method [17, 19, 20]. In these databases, cause of death and the occasion of hospitalization are coded according to the International Classification of Disease, 9th [21] and 10th revision [22]. In the initial linkage, performed at a mean followup of 17 months, a total 5.225 out of the 14.366 patient cohort experienced a valid endpoint (Table 2). Note that this initial overview gives only a global indication of the numbers (here death prevailed over admission) and will be updated for each sub study to be performed.

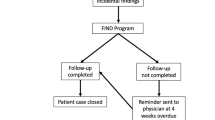

Evaluation of data

PROVIDI will consist of a series of studies investigating potentially predictive scan findings for specific groupings of disease entities (e.g. cardiovascular diseases). The study populations of these studies will consist of the patients that suffered the relevant disease(s) under study during the follow-up period, as well as a random sample of patients from the PROVIDI cohort (the sub-cohort). In each of these studies, patients with a reported CT indication directly related to the disease under study will be excluded, to ensure that the image findings under study can legitimately be defined as unrequested information, in keeping with the stated goals of PROVIDI. (Table 3, textbox, example study population) Fig. 3 shows the flowchart of the PROVIDI design.

We intend to analyse the scan findings both univariately and multivariately under study using Cox proportional hazard models, the most widely used statistical model for survival outcome in medical research. In multivariate analysis infromation readily available to radiologists in routine care (age, gender, CT indication, scanning parameters and quality) will be incorporated. The hazard ratios and standard errors will be modified based on robust variance estimates. These adaptations are to be carried out using the method according to Prentice, in which all sub cohort members are equally weighted [16]. Cases outside the sub cohort are not to be weighted before failure and at failure receive the same weight as members of the sub cohort. This method has been shown to resemble most closely estimates from a full-cohort analysis [23], without requiring a full analysis.

Discussion

Investigating which image findings have prognostic value and—perhaps more importantly—which findings do not, is the first step in a process that has great potential to improve clinical care. The findings of the PROVIDI study will be of great interest to radiologists, but also to referring physicians. The unique longitudinal study design, that places outcomes that matter to patients at its heart, gives this study the potential to meaningfully quantify the uncertainties facing diagnosticians and protect patients from potential over-diagnosis and over treatment. To illustrate: in the face of an absence of research investigating patient outcomes in routine-care, non-screening settings, radiologists are regularly responding defensively with exhaustive follow-up. An illustrative example is that of lung nodules, which are routinely detected on thoracic CT scans of all types, and which are frequently followed-up, despite evidence pointing to a low yield of significant pathology, at least in research/screening settings [7, 8].

By drawing on non-screening, routine clinical data it may both alleviate the dearth in radiological routine-care outcome data and serve as a basis for comparison with previous evidence from screening populations. A consequence of this study design is that patients at risk for a certain outcome will be identified using these models by radiologists while they may be already identified as such by other specialists, resulting in an overestimation of the clinical impact of certain incidental findings. Such double risk stratification would not have any negative effect for patients: the high risk indication from a radiologist is obtained freely (without additional radioation exposure) and can serve as a stimulus to verify whether optimal treatment has been initiated. In some cases this treatment is already optimal and a referring clinician can then ignore the ‘red flag’ if not, the referring specialist can consider additional investigations or start preventative treatment.

Translating the insights that might be gained from this study into clinical practice remains beyond the scope and means of PROVIDI itself but constitutes a crucial next step. Future clinical studies prospectively evaluating the efficacy and feasibility of implementing changes to clinical practice based upon PROVIDI’s findings could demonstrate the benefit of fully utilizing the potential of modern scanning technology.

Abbreviations

- Antonius :

-

St. Antonius hospital Nieuwegein

- AMC:

-

Academic medical center Amsterdam

- AZM:

-

Academic hospital Maastricht

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- Elkerliek:

-

Elkerliek hospital Helmond

- Gelre:

-

Gelre hospital Apeldoorn

- ICD:

-

International classification of disease

- kVp:

-

kiloVoltage peak

- MaS:

-

Milliampere seconds

- MDCT:

-

Multi detector row computed tomography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance Imaging

- PROVIDI:

-

PROgnostic Value of unrequested Information in Diagnostic Imaging

- UMCG:

-

University medical center Groningen

- UMCU:

-

University medical center Utrecht

- VUMC:

-

VU University medical center Amsterdam

References

RIVM. http://www.rivm.nl/ims/object_document/o22n1152.html. 2009.

RIVM. http://www.rivm.nl/ims/object_document/o23n1153.html. 2009.

Silverman JD, Paul NS, Siewerdsen JH. Investigation of lung nodule detectability in low-dose 320-slice computed tomography. Med Phys. 2009;36:1700–10.

Jacobs PC, Mali WP, Grobbee DE. Graaf Yvd Prevalence of incidental findings in computed tomographic screening of the chest: a systematic review. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2008;32:214–21.

Horton KM, Post WS, Blumenthal RS, Fishman EK. Prevalence of significant noncardiac findings on electron-beam computed tomography coronary artery calcium screening examinations. Circulation. 2002;106:532–4.

Munk MD, Peitzman AB, Hostler DP, Wolfson AB. Frequency and follow-up of incidental findings on trauma computed tomography scans: experience at a level one trauma center. J Emerg Med. 2010;38:346–50.

Iribarren C, Hlatky MA, Chandra M, Fair JM, Rubin GD, Go AS, Burt JR, Fortmann SP. Incidental pulmonary nodules on cardiac computed tomography: prognosis and use. Am J Med. 2008;121:989–96.

Xu DM, van der Zaag-Loonen HJ, Oudkerk M, Wang Y, Vliegenthart R, Scholten ET, Verschakelen J, Prokop M, de Koning HJ, van Klaveren RJ. Smooth or attached solid indeterminate nodules detected at baseline CT screening in the NELSON study: cancer risk during 1 year of follow-up. Radiology. 2009;250:264–72.

Berlin L, Berlin JW. Malpractice and radiologists in Cook County, IL: trends in 20 years of litigation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;165:781–8.

Machaalany J, Yam Y, Ruddy TD, Abraham A, Chen L, Beanlands RS, Chow BJ. Potential clinical and economic consequences of noncardiac incidental findings on cardiac computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1533–41.

van Klaveren RJ, Oudkerk M, Prokop M, Scholten ET, Nackaerts K, Vernhout R, van Iersel CA, Van den Bergh KA, van‘t WS, van der AC, Thunnissen E, Xu DM, Wang Y, Zhao Y, Gietema HA, de Hoop BJ, Groen HJ, de Bock GH, van OP, Weenink C. detected by volume CT scanning. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2221–9.

Budoff MJ. Ethical issues related to lung nodules on cardiac CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:W146.

Kalra MK, Abbara S, Cury RC, Brady TJ. Interpretation of incidental findings on cardiac CT angiography. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2007;70:324–5.

Mulshine JL, Jablons DM. Volume CT for diagnosis of nodules found in lung-cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2281–2.

Hlatky MA, Iribarren C. The dilemma of incidental findings on cardiac computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1542–3.

Prentice RL. A case-cohort design for epidemiologic cohort studies and disease prevention trials. Biometrika. 1986;73:1–11.

Paas GR, Veenhuizen KC. Research on the validity of the LMR. Utrecht: Prismant; 2002.

Mackenbach JP, Van Duyne WM, Kelson MC. Certification and coding of two underlying causes of death in The Netherlands and other countries of the European Community. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1987;41:156–60.

De Bruin A, Kardaun JW, Gast A, Bruin E, van Sijl M, Verweij G. Record linkage of hospital discharge register with population register: experiences at Statistics Netherlands. Stat J UN Econ Comm Eur 2004;23–32.

Reitsma JB, Kardaun JW, Gevers E, de Bruin A, van der Wal J, Bonsel GJ. [Possibilities for anonymous follow-up studies of patients in Dutch national medical registrations using the Municipal Population Register: a pilot study]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2003;147:2286–90.

http://icd9cm.chrisendres.com/index.php?action=contents. 2009.

http://apps.who.int/classifications/apps/icd/icd10online/. 2009.

Onland-Moret NC, van der AD, van der Schouw YT, Buschers W, Elias SG, van Gils CH, Koerselman J, Roest M, Grobbee DE, Peeters PH. Analysis of case-cohort data: a comparison of different methods. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:350–5.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the help with data collection and administrative support by Cees Haaring (UMCU), Karin Flobbe (AZM), Mirjam Borg (VUMC), Pascal Verzijl (Antonius), Jan Wolfers (AMC), Peter van Ooijen (UMCG), Willie Donkers (Elkerliek), and Robert Dragt (Gelre). This study was funded by a program grant from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research-Medical Sciences (NWO-MW) grant 40-00812-98-07-005). The funders had no involvement in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, the writing of the report, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

On behalf of the PROVIDI study group.

Please refer the “Appendix” section for PROVIDI study group members.

Appendix

Appendix

The PROVIDI study group consists of:

J. Laméris (Dept. of Radiology, Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam), C. van Kuijk (Dept. of Radiology, VU University Medical Center Amsterdam), W. ten Hove (Dept. of Radiology, Gelre Hospitals, Apeldoorn), M. Oudkerk (Dept. of Radiology, University Medical Center Groningen), Ay L. Oen(Dept. of Radiology, Elkerliek Hospital, Helmond), J. Wildberger (Dept. of Radiology, Academic Hospital Maastricht), J. van Heesewijk (Dept. of Radiology, St. Antonius Hospital, Nieuwegein), W. Mali (Dept. of Radiology, University Medical Center Utrecht) and Y. van der Graaf (Julius Center for Health Sciences and Primary Care, University Medical Center Utrecht).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Gondrie, M.J.A., Mali, W.P.T.M., Buckens, C.F.M. et al. The PROgnostic Value of unrequested Information in Diagnostic Imaging (PROVIDI) Study: rationale and design. Eur J Epidemiol 25, 751–758 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-010-9514-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-010-9514-9