Abstract

Between two popular teaching methods (i.e., balance method vs. inverse method) for equation solving, the main difference occurs at the operational line (e.g., +2 on both sides vs. −2 becomes +2), whereby it alters the state of the equation and yet maintains its equality. Element interactivity occurs on both sides of the equation in the balance method, but only on one side in the case of the inverse method. Thus, the balance method imposes twice as many interacting elements as the inverse method for each operational line. In two experiments, secondary students were randomly assigned to either the balance method or the inverse method to learn how to solve one-step, two-step, and three-or-more-step linear equations. Test results indicated that the interaction between method and type of equation favored the inverse method for equations involving higher element interactivity. Hence, by managing element interactivity, the efficiency of instruction for equation solving can be improved.

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

24 February 2017

An erratum to this article has been published.

References

Asquith, P., Stephens, A. C., Knuth, E. J., & Alibali, M. W. (2007). Middle school mathematics teachers’ knowledge of students’ understanding of core algebraic concepts: equal sign and variable. Mathematical Thinking and Learning, 9(3), 249–272. doi:10.1080/10986060701360910.

Ayres, P. (2006). Impact of reducing intrinsic cognitive load on learning in a mathematical domain. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 20(3), 287–298. doi:10.1002/acp.1245.

Blayney, P., Kalyuga, S., & Sweller, J. (2010). Interactions between the isolated–interactive elements effect and levels of learner expertise: experimental evidence from an accountancy class. Instructional Science, 38(3), 277–287. doi:10.1007/s11251-009-9105-x.

Cai, J., Lew, H. C., Morris, A., Moyer, J. C., Ng, S. F., & Schmittau, J. (2005). The development of students’ algebraic thinking in earlier grades: a cross-cultural comparative perspective. ZDM - The International Journal on Mathematics Education, 37, 5–15.

Carlson, R., Chandler, P., & Sweller, J. (2003). Learning and understanding science instructional material. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(3), 629–640. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.95.3.629.

Chen, O., Kalyuga, S., & Sweller, J. (2016). The expertise reversal effect is a variant of the more general element interactivity effect. Educational Psychology Review, 1–13.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for behavioral sciences. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Association.

Cramer, K., & Wyberg, T. (2009). Efficacy of different concrete models for teaching the part-whole construct for fractions. Mathematical Thinking and Learning, 11, 226–257. doi:10.1080/10986060903246479.

Gerjets, P., Scheiter, K., & Catrambone, R. (2004). Designing instructional examples to reduce intrinsic cognitive load: molar versus modular presentation of solution procedures. Instructional Science, 32(1–2), 33–58. doi:10.1023/b:truc.0000021809.10236.71.

Gopher, D., & Braune, R. (1984). On the psychophysics of workload: why bother with subjective measures? Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, 26(5), 519–532.

Knuth, E. J., Stephens, A. C., McNeil, N. M., & Alibali, M. W. (2006). Does understanding the equal sign matter? Evidence from solving equations. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 37(4), 297–312. doi:10.2307/30034852.

Leahy, W., & Sweller, J. (2008). The imagination effect increases with an increased intrinsic cognitive load. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 22(2), 273–283. doi:10.1002/acp.1373.

Linchevski, L., & Williams, J. (1999). Using intuition from everyday life in ‘filling’ the gap in children’s extension of their number concept to include the negative numbers. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 39(1/3), 131–147. doi:10.2307/3483164.

Mayer, R. E., Mathias, A., & Wetzell, K. (2002). Fostering understanding of multimedia messages through pre-training: evidence for a two-stage theory of mental model construction. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 8(3), 147–154. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.84.4.444.

McSeveny, A., Conway, R., & Wilkes, S. (2004). New signpost mathematics 8. Melbourne: Pearson Education Australia.

Miller, G. A. (1956). The magical number seven, plus or minus two: some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychological Review, 63(2), 81–97. doi:10.1037/h0043158.

Mock, J., & Wade, J. (2004). About maths. Sydney: Science Press.

Naismith, L. M., Cheung, J. J., Ringsted, C., & Cavalcanti, R. B. (2015). Limitations of subjective cognitive load measures in simulation-based procedural training. Medical Education, 49(8), 805–814.

Ngu, B. H., & Phan, H. P. (2016a). Unpacking the complexity of linear equations from a cognitive load theory perspective. Educational Psychology Review, 28, 95–118.

Ngu, B. H., & Phan, H. P. (2016b). Comparing balance and inverse methods on learning conceptual and procedural knowledge in equation solving: A Cognitive load perspective. Pedagogies: An International Journal, 11(1), 63–83.

Ngu, B. H., Chung, S. F., & Yeung, A. S. (2015). Cognitive load in algebra: element interactivity in solving equations. Educational Psychology, 35(3), 271–293.

Paas, F. (1992). Training strategies for attaining transfer of problem-solving skill in statistics: a cognitive-load approach. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(4), 429.

Paas, F., Tuovinen, J. E., Tabbers, H., & Van Gerven, P. W. M. (2003). Cognitive load measurement as a means to advance cognitive load theory. Educational Psychologist, 38(1), 63–71. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep3801_8.

Parker, M., & Leinhardt, G. (1995). Percent: a privileged proportion. Review of Educational Research, 65(4), 421–481. doi:10.3102/00346543065004421.

Pillay, H., Wilss, L., & Boulton-Lewis, G. (1998). Sequential development of algebra knowledge: a cognitive analysis. Mathematics Education Research Journal, 10(2), 87–102. doi:10.1007/bf03217344.

Pollock, E., Chandler, P., & Sweller, J. (2002). Assimilating complex information. Learning and Instruction, 12(1), 61–86. doi:10.1016/s0959-4752(01)00016-0.

Reed, S. K. (1987). A structure-mapping model for word problems. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 13(1), 124–139. doi:10.1016/0010-0285(80)90013-4.

Rittle-Johnson, B., & Alibali, M. W. (1999). Conceptual and procedural knowledge of mathematics: does one lead to the other? Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(1), 175–189. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.91.1.175.

Rittle-Johnson, B., & Star, J. R. (2007). Does comparing solution methods facilitate conceptual and procedural knowledge? An experimental study on learning to solve equations. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99, 561–574. doi:10.1037//1082-989x.7.2.147.

Star, J., & Newton, K. (2009). The nature and development of experts’ strategy flexibility for solving equations. ZDM, 41(5), 557–567. doi:10.1007/s11858-009-0185-5.

Sweller, J. (2012). Human cognitive architecture: why some instructional procedures work and others do not. In K. Harris, S. Graham, & T. Urdan (Eds.), APA educational psychology handbook, (vol. 1, pp. 295–325). Washington, D.C: American Psychological Association.

Sweller, J., & Cooper, G. A. (1985). The use of worked examples as a substitute for problem solving in learning algebra. Cognition and Instruction, 2(1), 59–89. doi:10.1207/s1532690xci0201_3.

Sweller, J., Ayres, P., & Kalyuga, S. (2011). Cognitive load theory. New York: Springer.

van Gog, T., & Paas, F. (2008). Instructional efficiency: revisiting the original construct in educational research. Educational Psychologist, 43(1), 16–26. doi:10.1080/00461520701756248.

van Gog, T., Kester, L., & Paas, F. (2011). Effects of worked examples, example-problem, and problem-example pairs on novices’ learning. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36(3), 212–218. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2010.10.004.

Warren, E., & Cooper, T. J. (2009). Developing mathematics understanding and abstraction: the case of equivalence in the elementary years. Mathematics Education Research Journal, 21, 76–95. doi:10.1007/bf03217546.

Young, J. Q., Irby, D. M., Barilla-LaBarca, M.-L., ten Cate, O., & O’Sullivan, P. S. (2016). Measuring cognitive load: mixed results from a handover simulation for medical students. Perspectives on medical education, 5(1), 24–32.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

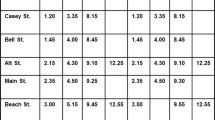

The original version of this article was revised: Alignment of Tables 1 and 3 entries were incorrect.

An erratum to this article is available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-017-9402-x.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ngu, B.H., Phan, H.P., Yeung, A.S. et al. Managing Element Interactivity in Equation Solving. Educ Psychol Rev 30, 255–272 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-016-9397-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-016-9397-8