Abstract

In this paper we analyse structural change and its implications for labor productivity growth in Kazakhstan, Malawi, and Zambia, three resource-dependent countries, during the resource boom that lasted from 2001 to 2013. We pay particular attention to the effects of labor heterogeneity by assessing the demand for pre-determined occupations. The effects of structural change on heterogeneous labor markets are studied by developing a model to explain the observed patterns of labor migration between sectors. We use labor force survey data from Kazakhstan and census microdata for Malawi and Zambia available from the IPUMS International database. In-depth examinations are performed using a decomposition technique and multinomial logit regression to examine labor demand patterns. Results show that private services experienced the largest increase in employment across all occupations and relative skill deepening. Substantial decreases in managers occurred in public services. The results indicate that structural change is fundamental in shaping the allocation of individuals across different occupations within the labor market. Moreover, during a resource boom, the results indicate that the public sector experiences a skill-drain that may affect the quality of governance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The static-shift effect is calculated as the sum of relative changes in the share of labor across sectors between a base year and a terminal year, weighted by the value of labor productivity in the base year.

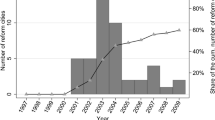

For calculating the contribution of structural change to labor productivity, we used the Groningen Growth and Development Center (GGDC) database, which provides employment and real-valued added statistics for both Malawi and Zambia disaggregated into ten sectors (Timmer and de Vries 2007, 2009). We collected our own data from Kazakhstan (Labor Force Survey and National Accounts). To maintain consistency with the GGDC data, we followed the data compilation procedures outlined by the GGDC authors.

According to user privileges of the IPUMS International dataset, we acknowledge the statistical agencies that originally produced the data; specifically, the National Statistical Office of Malawi and the Central Statistical Office of Zambia.

The World Bank (2017) defines low-income economies as those with a GNI per capita of $1005 or less in 2016; lower middle-income economies are those with a GNI per capita between $1006 and $3955; upper middle-income economies are those with a GNI per capita between $3956 and $12,235; high-income economies are those with a GNI per capita of $12,236 or more.

However, with high mineral prices the mineral sector’s total exports in 2007 were estimated at USD 725 million (World Bank 2018).

Public services include public administration, defence, education, health care, social services, and utilities. Private services include wholesale and retail trade; hotel and restaurant services; transport, storage and communications; finance, insurance and real estate; and business and technical services.

Chenery et al. (1986) provide an in-depth discussion on the criteria used to distinguish semi-industrialized economies.

At the Kiel Institute of World Economics during the 1970’s, fifteen semi-industrialized economies were studied to examine the process of economic development (Donges 1976). The Kiel Institute of World Economics defined semi-industrialized countries as those economies that have already left the early phase of industrialization (in which capital, skill and infrastructural requirements are rather low); but, have not joined the ranks of industrialized countries (i.e., semi-industrialized countries may be perceived as middle-income countries).

We follow Spatafora et al. (2012) and separate the private services into modern and traditional services. We define traditional private-sector services to include construction; wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles; accommodation and food service activities; and transportation and storage.

We define modern private-sector services to include financial and insurance activities; real estate activities; professional, scientific and technical activities; and administrative and support service activities.

Public services comprise public utilities and government services.

We could incorporate manufactures into both the utility function as well as the production function in Sect. 3.2; however, this would not change the outcome of our model unless the income elasticity of manufactures is greater than one. Furthermore, manufacturing is a very small component of most low- and middle-income, resource-dependent countries. For example, manufacturing employed only 6.8% of Kazakhstan’s labor force in 2011; 5.8% of Malawi’s labor force in 2008; and 4.4% of Zambia’s labor force in 2010.

Falvey and Gemmell (1996) find government services to be price elastic and income unit elastic.

The assumption of only two skill levels can be relaxed without any major effects if the third factor is the least intensively used factor. We use three skill levels in our empirical analysis.

The percentage of labor employed in mining for Malawi in 1998 and 2008 were 0.06% and 0.13%, respectively; for Zambia in 2000 and 2010 were 2.03% and 2.46%, respectively; for Kazakhstan in 2001 and 2011 were 3.63% and 2.63%, respectively (authors’ calculations). Iinput-output analysis of the South African economy by Stilwell et al. (2000) finds few linkages between mining and the rest of the economy. Finally, studies from resource-dependent high-income jurisdictions show that output growth during the 2001–2013 resource boom was primarily driven by capital growth [see Centre for the Study of Living Standards (2012) for Alberta and Mason (2013) for Australia]. As both the oil and gas and mining industries are extensively global, we assume a similar pattern for Kazakhstan, Malawi and Zambia.

This corresponds well with Rodrik’s (2007) findings that during periods of sharp global competition states are pushed to implement new labor market reforms, reduce government spending, or sharpen economic and policy divergence through innovative institutional measures and new spending initiatives that create new policy spaces. All these initiatives require high-skilled labor in the public sector.

We could introduce inequality in resource rent earnings, similar to Howie and Atakhanova (2014); but, given the Linear Expenditure System utility function the aggregate expenditure share on each good would still be \(\alpha_{n}\).

The increase of factors of production do not affect the labor demand dynamics as the additional skill level is the one least intensively used in the production process.

Katz and Murphy (1992) state that under the assumption of fixed relative wages between-sector results will be downward biased in groups with relative wage increases.

Due to data availability, the base year for Kazakhstan is 2001; for Malawi is 1998; and for Zambia 2000.

Between 1990 and 1995, Kazakhstan’s gross agriculture output decreased 47% and agricultural labor productivity decreased 63% (Macours and Swinnen 2002).

The Kazakhstani Ministry of Agriculture's budget increased from 26 billion tenge in 2001–81 billion tenge in 2005, and its share of the total central budget went from 2.5% to 6.5% (Petrick and Pomfret 2016).

We acknowledge that the time periods for each country are not consistent. However, as we are mainly interested in examining the changes in probabilities of selecting employment between the private and public sectors for professionals, managers, clerks, service workers, and laborers the differing time periods have minimal effects on our results. This is supported by the fact that we do not compare results across countries.

In Kazakhstan, unskilled farmers were classified as those workers that worked in the agricultural sector and have completed up to 9 years of education. In Kazakhstan, the data indicate that less than 0.1% of unskilled farmers worked in public sector in KZ in both 2001 and 2011. In both Malawi and Zambia, unskilled farmers were classified as those workers that worked in the agricultural sector and have completed up to 6 years of education. In Malawi, the data indicate that 3.0% and 0.5% of unskilled farmers worked in public sector in 1998 and 2008, respectively. In Zambia, the data indicate that 1.4% and 0.2% of unskilled farmers worked in public sector in 1998 and 2008, respectively.

Sales workers in Kazakhstan were classified as those workers that worked in the ILO’s ISCO-88 “Models, Salespersons and Demonstrators” occupations. In Kazakhstan, the data indicate that 0.5% and 0.2% of sales workers worked in public sector in 2001 and 2011, respectively. As the IPUMS data “Occupation, ISCO general” aggregates “Personal and Protective Service Workers” with “Models, Salespersons and Demonstrators”, we use country-specific data for Malawi and Zambia to extract and exclude “Models, Salespersons and Demonstrators”. In Malawi, the data indicate that 1.5% and 0.3% of sales workers worked in public sector in 1998 and 2008, respectively. In Zambia, the data indicate that 0.6% and 2.6% of sales workers worked in public sector in 2000 and 2010, respectively.

Craft workers in Kazakhstan, Malawi and Zambia were classified as those workers that worked in the ILO’s ISCO-88 “Craft and Related Trades Workers”. In Kazakhstan, the data indicate that 3.2% and 1.0% of craft workers worked in public sector in 2001 and 2011, respectively. In Malawi, the data indicate that 3.8% and 1.7% of sales workers worked in public sector in 1998 and 2008, respectively. In Zambia, the data indicate that 2.0% and 0.9% of sales workers worked in public sector in 2000 and 2010, respectively.

The mining and oil and gas extraction sector in Alberta experienced − 6.1% annual growth of multifactor productivity during 1997–2010 (Centre for the Study of Living Standards 2012).

References

Allcott H, Keniston D (2017) Dutch disease or agglomeration? The local economic effects of natural resource booms in modern America. Rev Econ Stud 85(2):695–731

Atakhanova Z (2018) Oil-and-Gas services in Kazakhstan. In: Anderson K, Capannelli G, Ginting E, and Taniguchi K (eds) Kazakhstan accelerating economic diversification. Asian Development Bank, Manila, Philippines, pp 122–141

Autor D, Katz L, Krueger A (1998) Computing inequality: have computers changed the labor market? Q J Econ 113(4):1169–1213

Basedau M (2005) Context matters—rethinking the resource curse in Sub-Saharan Africa. GIGA working paper no 1

Benjamin NC, Devarajan S, Weiner RJ (1989) The ‘Dutch’ disease in a developing country: oil reserves in Cameroon. J Dev Econ 30(1):71–92

Berman E, Bound J, Griliches Z (1994) Changes in the demand for skilled labor within US manufacturing: evidence from the annual survey of manufactures. Q J Econ 109(2):367–397

Bhorat H, Hodge J (1999) Decomposing shifts in labour demand in South Africa. S Afr J Econ 67(3):155–168

Bjørnland HC, Thorsrud LA (2016) Boom or gloom? Examining the Dutch disease in two-speed economies. Econ J 126(598):2219–2256

Blank RM (1985) An analysis of workers’ choice between employment in the public and private sectors. Ind Labor Relat Rev 38(2):211–224

Bloch FE, Smith SP (1977) Human capital and labor market employment. J Hum Resour 12(4):550–560

Caselli F, Michaels G (2009) Resource abundance, development, and living standards: evidence from oil discoveries in Brazil. National Bureau of Economic research working paper, 15550

Centre for the Study of Living Standards (2012) The Alberta productivity story, 1997–2010. The Government of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta. https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/12c02d5e-12ce-4751-a4f4-3d2d12f09b16/resource/511df1f7-52b9-4f0a-94f4-cc498aee731e/download/6582918-2012-alberta-productivity-story-1997-2010-2012-11-14.pdf.. Accessed 12 Mar 2018

Chansomphou V, Ichihashi M (2013) Structural change, labor productivity growth, and convergence of BRIC countries. Hiroshima University, Graduate School for International Development and Cooperation Research Paper (No. 3–5)

Chenery HB, Robinson S, Syrquin M (1986) Industrialization and growth. World Bank, Washington

Cohen JM (1995) Capacity building in the public sector: a focused framework for analysis and action. Int Rev Admin Sci 61(3):407–422

Corden WM (2012) Dutch disease in Australia: policy options for a three-speed economy. Aust Econ Rev 45(3):290–304

Corden WM, Neary JP (1982) Booming sector and de-industrialisation in a small open economy. Econ J 92(368):825–848

Dagsvik JK, Strøm S (2006) Sectoral labour supply, choice restrictions and functional form. J Appl Econ 21(6):803–826

Davis GA (1995) Learning to love the Dutch disease: evidence from the mineral economies. World Dev 23(10):1765–1779

De Boer P, Missaglia M (2006) Economic consequences of intifada. Econ Syst Res 18(1):97–106

De Vries GJ, Erumban AA, Timmer MP, Voskoboynikov I, Wu HX (2012) Deconstructing the BRICs: structural transformation and aggregate productivity growth. J Comp Econ 40(2):211–227

Diao X, McMillan M, Rodrik D (2017) The recent growth boom in developing economies: a structural change perspective (working paper 23132). National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA. https://www.nber.org/papers/w23132.pdf. Accessed 10 Mar 2018

Donges JB (1976) A comparative survey of industrialization policies in fifteen semi-industrial countries. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv 112(4):626–659

Doyle M-A (2014) Labour movements during the resources boom. Reserve Bank Aust Bull 4:7–16

Fabricant S (1942) Employment in Manufacturing 1899–1939. Natl Bur Econ Res, New York

Falvey RE, Gemmell N (1996) Are services income-elastic? Some new evidence. Rev Income Wealth 42:257–269

Fardmanesh M (1991) Dutch disease economics and oil syndrome: an empirical study. World Dev 19(6):711–717

Fourastié J (1949) Le grand espoir du XXe siècle: progrès technique, progrès économique, progrès social. Presses Universitaires de France, Paris

Fuinhas JA, Marques AC, Couto AP (2015) Oil rents and economic growth in oil producing countries: evidence from a macro panel. Econ Change Restruct 48(3–4):257–279

Ghura D, Pattillo C (2012) Macroeconomic policy frameworks for resource-rich developing countries. International Monetary Fund, Washington

Goderis B, Malone SW (2011) Natural resource booms and inequality: theory and evidence. Scand J Econ 113(2):388–417

Gollin D, Jedwab R, Vollrath D (2016) Urbanization with and without Industrialization. J Econ Growth 21(1):35–70

Green F, Dickerson A, Carruth, A, Campbell D (2001) An analysis of subjective views of job insecurity. University of Kent Department of Economics discussion paper no. 01, 08

Halek M, Eisenhauer JG (2001) Demography of Risk Aversion. J Risk Insur 68(1):1–24

Hall R (1972) Turnover in the labor force. In: Brookings papers on economics activity. The Brookings Institution, Washington, pp 709–56

Howie P (2017) Kazakhstan’s diversification strategy—Are policies building linkages and promoting competition? In: Mahroum S, Al-Saleh Y (eds) Economic diversification policies in natural resource-rich economies. Routledge, New York, pp 203–235

Howie P (2018) Policy transfer and diversification in resource-dependent economies: lessons for Kazakhstan from Alberta. Politics Policy 46(1):110–140

Howie P, Atakhanova Z (2014) Resource boom and inequality: Kazakhstan as a case study. Resour Policy 39:71–79

International Monetary Fund [IMF] (2013) Labor market reforms to boost employment and productivity in the GCC. International Monetary Fund, Washington

Jedwab R, Gollin D, Vollrath D (2013) Urbanization with and without industrialization. Institute for International economic policy working paper IIEP–WP–2014–1. http://www2.gwu.edu/~iiep/assets/docs/papers/Jedwab_IIEPWP_2014-1.pdf. Accessed 28 Sept 2018

Katz LF, Murphy KM (1992) Changes in relative wages, 1963–1987: supply and demand factors. Q J Econ 107(1):35–78

Keane MP, Prasad E (1996) The employment and wage effects of oil price changes: a sectoral analysis. Rev Econ Stat 78(3):389–400

Kuusk A, Staehr K, Varblane U (2015) Sectoral change and labour productivity growth during boom, bust and recovery in Central and Eastern Europe. Econ Change Restruct 50(1):21–43

Kuznets S (1979) Growth and structural shifts. In: Galenson W (ed) Economic growth and structural change in Taiwan. The Postwar Experience of the Republic of China. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, US, pp 15–131

Lee D, Wolpin KI (2006) Intersectoral labor mobility and the growth of the service sector. Econometrica 74(1):1–46

Long JS, Freese J (2014) Regression models for categorical dependent variables using stata, 3rd edn. Stata Press, College Station

Macours K (2000) Impact of initial conditions and reform policies on agricultural performance in Central and Eastern Europe, the Former Soviet Union, and East Asia. Am J Agr Econ 82(5):1149–1155

Macours K, Swinnen JFM (2002) Patterns of agrarian transition. Econ Dev Cult Change 50(2):365–394

Maddison A (1987) Growth and slowdown in advanced capitalist economies: techniques of quantitative assessment. J Econ Lit 25:649–698

Mason G (2013) Investigating New Zealand–Australia productivity differences: new comparisons at industry level. New Zealand productivity commission working paper 2013/02

McMillan M, Rodrik D (2011) Globalization, structural change and productivity growth (working paper 17143). National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA. https://www.nber.org/papers/w17143. Accessed 2 Mar 2018

McMillan M, Rodrik D, Verduzco-Gallo I (2014) Globalization, structural change, and productivity growth, with an update on Africa. World Dev 63:11–32

Minnesota Population Center [IPUMS] (2018) Integrated public use microdata series, International: version 7.1 [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN. https://doi.org/10.18128/D020.V7.1

Mulungu K, Ng’ombe JN (2017) Sources of economic growth in Zambia, 1970–2013: a growth accounting approach. Economies 5(2):1–23

Ngai LR, Pissarides CA (2007) Structural change in a multisector model of growth. Am Econ Rev 97(1):429–443

O’Mahony M, Van Ark B (2003) EU productivity and competitiveness: an industry perspective. Can Europe resume the catching-up process. European Commission, Italy

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD] (2014) Energy subsidies and climate change in Kazakhstan. Paris. https://www.oecd.org/env/outreach/Energy%20subsidies%20and%20climate%20change%20in%20Kazakhstan.pdf. Accessed 20 Oct 2018

Petrick M, Pomfret R (2016) Agricultural policies in Kazakhstan, Leibniz Institute of Agricultural Development in Transition Economies discussion paper no. 155

Pistaferri L (2003) Anticipated and unanticipated wage changes, wage risk, and intertemporal labor supply. J Labor Econ 21(3):729–754

Rampini AA (2004) Entrepreneurial activity, risk, and the business cycle. J Monet Econ 51(3):555–573

Rodrik D (2007) Industrial development: some stylized facts and policy directions. In: United Nations Commission on Sustainable Development (ed.) Industrial development for the 21st century: sustainable development perspectives. United Nations Publication, New York, pp 7–28

Ruehle AA, Kulkarni KG (2011) Dutch disease and the Chilean copper boom–an empirical analysis. Int J Edu Econ Dev 2(1):61–80

Saccone D, Valli V (2009) Structural change and economic development in China and India. University of Torino Department of Economics research paper no. 7/2009–GE

Shahiduzzaman M, Layton A, Alam K (2015) On the contribution of information and communication technology to productivity growth in Australia. Econ Change Restruct 48(3–4):281–304

Shaw KL (1987) The quit propensity of married men. J Labor Econ 5(4):533–560

Silberberg E, Suen W (2001) The structure of economics: a mathematical approach, 3rd edn. McGraw-Hill, Singapore

Spatafora N, Anand R, Mishra S (2012) Structural transformation and the sophistication of production. International Monetary fund working paper no. 12–59. https://www.imf.org/~/media/Websites/IMF/imported-full-text-pdf/external/pubs/ft/wp/2012/_wp1259.ashx. Accessed 24 Feb 2018

Stelcner M, Van der Gaag J, Vijverberg W (1989) A switching regression model of public–private sector wage differentials in Peru: 1985–86. J Hum Resour 24(3):545–559

Stilwell L, Minnitt R, Monson T, Kuhn G (2000) An input–output analysis of the impact of mining on the South African economy. Resour Policy 26:17–30

Suleymenov M (2009) Master Plan Razvitiya Proizvodstva Zerna i Ego Glubokoy Pererabotki’ [Master Plan of the Development of Grain Production and Its Deep Processing]. Ministry of Agriculture of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Almaty

Syrquin M (1984) Resource allocation and productivity growth. In: Syrquin M, Taylor L, Westphal LE (eds) Economic structure performance—essays in honor of Hollis B. Chenery. Academic Press, Orlando, pp 75–101

Tapp S (2007) The dynamics of sectoral labour adjustment. Queen’s University Economics Department working paper 1141

Tapp S (2011) Lost in transition: the costs and consequences of sectoral labour adjustment. Can J Econ 44(4):1264–1296

Timmer MP, de Vries GJ (2007) A cross-country database for sectoral employment and productivity in Asia and Latin America, 1950–2005. GGDC Research Memorandum 98. Groningen Growth and Development Centre, Groningen, the Netherlands. https://www.rug.nl/research/portal/files/2790748/gd98online.pdf. Accessed 15 Feb 2018

Timmer MP, de Vries GJ (2009) Structural change and growth accelerations in Asia and Latin America: a new sectoral data set. Cliometrica 3(2):165–190

Timmer MP, Szirmai A (2000) Productivity growth in Asian manufacturing: the structural bonus hypothesis examined. Struct Change Econ Dyn 11(4):371–392

Timmer MP, Voskoboynikov IB (2014) Is mining fuelling long-run growth in Russia? Industry productivity growth trends since 1995. Rev Income Wealth 60(S2):S398–S422

Topp V, Kulys T (2014) On productivity: the influence of natural resource inputs. Int Product Monit 27(2):64–78

Van der Gaag J, Vijverberg W (1988) A switching regression model for wage determinants in the public and private sectors of a developing country. Rev Econ Stat 70(2):244–252

World Bank (2009) Malawi mineral sector review source of economic growth and development report no. 50160-MW. http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTRANETENVIRONMENT/Resources/MALAWIMINERALSECTORREVIEW.pdf. Accessed 24 Oct 2018

World Bank (2017) New country classifications by income level: 2017–2018. http://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/new-country-classifications-income-level-2017-2018. Accessed 21 Oct 2018

World Bank (2018) World Bank development indicators—GDP growth (annual %). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG. Accessed 24 Oct 2018

Yap L (1976) Internal migration and economic development in Brazil. Q J Econ 90(1):119–137

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the editor and the two anonymous referees for their helpful and constructive comments. The usual disclaimer applies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Howie, P., Atakhanova, Z. Heterogeneous labor and structural change in low- and middle-income, resource-dependent countries. Econ Change Restruct 53, 297–332 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10644-018-9242-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10644-018-9242-9