Abstract

The major objectives of this article are to identify the inter-regional and inter-sector wage differentials that are attributed to the institutional restriction on labor mobility (the hukou system), and then to simulate the impact that the removal of the restriction would have on the Chinese economy. Our simulation results reveal that the removal of the hukou system would be accompanied by a massive migration to cities. The degree by which the labor force would decrease with the removal of the hukou system is higher in rural industry than in agriculture, suggesting that the absence of job qualifications would prevent the vast majority of farmers from changing their occupations. Should off-farm employment opportunities in cities for rural migrants be rationed, the elimination of the hukou system would exacerbate rather than cure the problem of unemployment in urban labor markets, which would adversely affect distributional consequences at the national level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

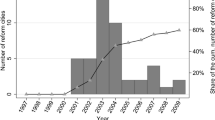

The hukou system implemented in 1951 was originally designed not to control rural-urban migration, but rather to monitor population movements (Chan and Zhang 1999). The grain quota system was abolished in the late-1990s for most parts of the county. The rural land contract law enacted in 2002 is considered to lower the farmers’ risk of losing their usufruct to farmland and therefore facilitate migration. During the period when market economy had yet to develop, it was impossible for rural people to migrate to cities and to live there because they were excluded from the ration system. It is not until the mid-1980s that rural people were allowed to migrate to cities temporarily without obtaining urban hukou, but their access to subsidized benefits is still limited even today (Fan 2002).

According to Zhang and Song (2003), 89% of inter-province migrants come from the interior region at the end of the 1990s, and 76% of inter-province migrants move to the coastal region. Liang and Ma (2004) that analyze the Population Census, 2000, argue that the inter-county temporary migration during 1995–2000 is nearly three times larger than the inter-county permanent migrant population, and more than half of inter-county migrants move inter-provincially in 2000.

The provinces that are contained in each subgroup is as follows: NC: Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Jiangsu, and Shandong; SC: Shanghai, Zhejiang, Fujian, Guangdong, and Hainan; NE: Liaoning, Jilin, and Heilongjiang; NI: Shanxi, Anhui, and Henan; SI: Jiangxi, Hubei, and Hunan; NW: Inner Mongolia, Shaanxi, Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia, and Xinjiang; and SW: Guangxi, Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan, and Tibet.

This is consistent with the findings of de Brauw et al. (2002), and Knight and Song (1999, 2003) that rural people with higher educational backgrounds are likely to find off-farm work more easily than those with less education, but there is no significant difference in their probability of becoming migrants or TVE employees. Borjas (1987) argues a negative-selection mechanism in which those with below-average skill levels in their home countries have a strong incentive to migrate to developed countries. Chiquiar and Hanson (2005) demonstrate that the negative-selection hypothesis is not always supported if migration cost is inversely related to educational attainments.

The contribution of the hukou system to the wage differential between agriculture in the interior region and urban formal sectors in the costal region can be defined as \( {{\left( {w_{2}^{n} - w_{1}^{n} } \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\left( {w_{2}^{n} - w_{1}^{n} } \right)} {\left( {W_{2}^{m} - w_{2}^{0} } \right)}}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {\left( {W_{2}^{m} - w_{2}^{0} } \right)}} \). It ranges from 20% to 26%. These figures are somewhat smaller than those used in the simulation analysis of Shi (2002). However, when the contribution is measured by \( {{\left( {w_{2}^{n} - w_{1}^{n} } \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\left( {w_{2}^{n} - w_{1}^{n} } \right)} {\left( {w_{2}^{m} - w_{2}^{0} } \right)}}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {\left( {w_{2}^{m} - w_{2}^{0} } \right)}} \), it goes up to above 50%.

We assume that transportation costs do not account for the intra-regional wage gap due to the recent development of the efficient transportation system (Rozelle et al. 1999).

A caveat is that we do not take into account the mechanism by which the hukou reinforces a social order of stratification. As Fan (2002), Liu (2005), and Wu and Treiman (2007) discuss, the institutional divide deprives rural people of an incentive to invest in their children’s education. Ma (2001) discusses that rural people who successfully participate in urban labor markets are able to improve their skills through on the job training, while those who fail to do so miss such opportunity.

According to Liang and Ma (2004) that analyze migration in China, the inter-county migrants increased from 43 million to 79 million between 1995 and 2000. Among the 79 million, 59 million (74%) are people working in a different place where they were born without changing their household registrations. The rest are registered or permanent migrants. Note that these numbers include not only people who migrated to cities but also those who moved to rural areas.

The agricultural production at the regional level was so adjusted that the estimated value of production might be equal to the aggregate level. Thus, the lack of data for these provinces does not affect the simulation results significantly.

Since annual sales of TVEs were 0.75 million Yuan on average in 2004, most TVEs are not thought to be included in this category.

The Ministry of Agriculture announced that the surplus rate of agricultural labor in China reached 47% in 2004. Simulation (1) reveals that agricultural labor would decrease by only 11.4% with the elimination of the hukou system, indicating that the ignorance of farmers’ poor job qualifications over-estimates the surplus rate.

Although the rate of urban unemployment in China shows an increasing trend for the past decade, it remains at 4.2% in 2004 (China Labour Statistical Yearbook, 2006). It is widely believed that the official data do not reflect the reality mainly because laid-off workers are excluded from the statistics. According to Xue and Zhong (2006), the urban unemployment rate reaches 11.5% in 2000 if the necessary adjustment is made.

The urbanization rate in China is believed to be above 40% at present, higher than our estimation. This discrepancy is due to the fact that the official classification includes a part of agricultural residents as urban population (Lee 1989).

A new phenomenon of poverty and unemployment in urban China has attracted academic and political concerns since the mid-1990s. It is associated not only with a rapid increase in unemployed and laid-off workers of state-owned enterprises but also with a great influx of migrants (Meng 2006; Xue and Zhong 2006).

From the production function specified in Eq. 21 with a parametric restriction of \( \beta_{i} = 1 - \alpha_{i} \), \( ML_{1} \left( {AL_{1} + UE_{2} ,\;K_{1} + \Updelta K_{1} } \right) = w_{1} ^\prime \) can be written as \( A_{1} \alpha_{1} \left( {{{K_{1} ^\prime } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{K_{1} ^\prime } {L_{1} ^\prime }}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {L_{1} ^\prime }}} \right)^{{1 - \alpha_{1} }} = w_{1} ^\prime \), where \( L_{1} ^\prime = AL_{1} + UE_{2} \) and \( K_{1} ^\prime = K_{1} + \Updelta K_{1} \), meaning that \( \Updelta K_{1} \) is so determined that \( {{K_{1} ^\prime } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{K_{1} ^\prime } {L_{1} ^\prime }}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {L_{1} ^\prime }} \) may be maintained at the level of Simulation (2) or (3). This holds true even when urban informal sectors undertake new investment (\( \Updelta K_{2} \)) for absorbing unemployed workers. Since \( {{K_{2} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{K_{2} } {L_{2} }}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {L_{2} }} > {{K_{1} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{K_{1} } {L_{1} }}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {L_{1} }} \) is met for all regions, we have \( \Updelta K_{2} > \Updelta K_{1} \).

References

Ash RF, Edmonds RL (1998) China’s land resources, environment and agricultural production. China Q 156:836–879

Au CC, Henderson JV (2006) How migration restrictions limit agglomeration and productivity in China. J Dev Econ 80:350–388. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2005.04.002

Borjas GJ (1987) Self-selection and the earnings of immigrants. Am Econ Rev 77:531–553

Carter CA, Estrin AJ (2005) Opening of China’s trade, labour market reform and impact on rural wages. World Econ 28:823–839. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9701.2005.00708.x

Chan KW, Zhang L (1999) The hukou system and rural–urban migration in China: processes and changes. China Q 160:818–855

Chiquiar D, Hanson GH (2005) International migration, self-selection, and the distribution of wages: evidence from Mexico and the United States. J Polit Econ 113:239–281. doi:10.1086/427464

de Brauw A, Huang J, Rozelle S, Zhang L, Zhang Y (2002) The evolution of China’s rural labor markets during the reforms. J Comp Econ 30:329–353. doi:10.1006/jcec.2002.1778

Fan CC (2002) The elite, the natives, and the outsiders: migration and labor market segmentation in urban China. Ann Assoc Am Geogr 92:103–124. doi:10.1111/1467-8306.00282

Fan CC (2005) Modeling interprovincial migration in China, 1985–2000. Eurasian Geogr Econ 46:165–184. doi:10.2747/1538-7216.46.3.165

Fan CC (2008) China on the move: migration, the sate, and the household. Routledge, London and New York

Guang L, Zheng L (2005) Migration as the second-best option: local power and off-farm employment. China Q 181:22–45. doi:10.1017/S0305741005000020

Guo F, Iredale R (2004) The impact of hukou status on migrants’ employment: findings from the 1997 Beijing migrant census. Int Migr Rev 38:709–731

Hare D (2002) The determinants of job location and its effect on migrants’ wages: evidence from rural China. Econ Dev Cult Change 50:557–579. doi:10.1086/342356

Harris JR, Torado MP (1970) Migration, unemployment and development: a two-sector analysis. Am Econ Rev 60:126–142

Hertel T, Zhai F (2006) Labor market distortions, rural–urban inequality and the opening of China’s economy. Econ Model 23:76–109. doi:10.1016/j.econmod.2005.08.004

Jefferson GH, Singh I (1999) Enterprise reform in China: ownership, transition, and performance. Oxford University Press, New York

Johnson DG (2003) Provincial migration in China in the 1990s. China Econ Rev 14:22–31. doi:10.1016/S1043-951X(02)00085-8

Kanbur R, Zhang X (1999) Which regional inequality? The evolution of rural–urban and inland-coastal inequality in China from 1983 to 1995. J Comp Econ 27:686–701. doi:10.1006/jcec.1999.1612

Knight J, Song L (1999) Employment constraints and sub-optimality in Chinese enterprises. Oxf Econ Pap 51:284–299. doi:10.1093/oep/51.2.284

Knight J, Song L (2003) Chinese peasant choices: migration, rural industry or farming. Oxf Dev Stud 31:123–147. doi:10.1080/13600810307427

Knight J, Song L, Huaibin J (1999) Chinese rural migration in urban enterprises: three perspectives. J Dev Stud 35(3):73–104. doi:10.1080/00220389908422574

Lee YF (1989) Small town and China’s urbanization level. China Q 120:771–786

Liang Z, Ma Z (2004) China’s floating population: new evidence from the 2000 census. Popul Dev Rev 30:467–488. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2004.00024.x

Liang Z, White MJ (1997) Market transition, government policies, and interprovincial migration in China: 1983–1988. Econ Dev Cult Change 45:321–339. doi:10.1086/452276

Lin JY, Wang G, Zhao Y (2004) Regional inequality and labor transfers in China. Econ Dev Cult Change 52:578–603. doi:10.1086/421481

Liu Z (2005) Institution and inequality: the hukou system in China. J Comp Econ 33:133–157. doi:10.1016/j.jce.2004.11.001

Ma Z (2001) Urban labour-force experience as a determinant of rural occupation change: evidence from recent urban-rural return migration in China. Environ Plan A 33:237–255. doi:10.1068/a3386

Meng X (2006) Economic restructuring and income inequality in urban China. In: Shi L, Sato H (eds) Unemployment, inequality and poverty in urban China. Routledge, London and New York

Meng X, Zhang J (2001) The two-tier labor market in urban China: occupational segregation and wage differentials between urban residents and rural migrants in Shanghai. J Comp Econ 29:485–504. doi:10.1006/jcec.2001.1730

Ravallion M, Chen S (2007) China’s (uneven) progress against poverty. J Dev Econ 82:1–42. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2005.07.003

Rozelle S, Guo L, Shen M, Hughart A, Giles J (1999) Leaving China’s farms: survey results of new paths and remaining hurdles to rural migration. China Q 158:367–393

Shi X (2002) Empirical research on urban-rural income differentials: the case of China. Mimeo, CCER, Beijing University

Smil V (1999) China’s agricultural land. China Q 158:414–429

ten Raa T, Pan H (2005) Competitive pressures on China: income inequality and migration. Reg Sci Urban Econ 35:671–699. doi:10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2004.12.001

Wang F (2004) Reformed migration control and new targeted people: China’s hukou system in the 2000s. China Q 177:115–132. doi:10.1017/S0305741004000074

Wang GT, Hu X (1999) Small town development and rural urbanization in China. J Contemp Asia 29:76–94. doi:10.1080/00472339980000051

West LA, Zhao Y (2000) Rural labor flows in China. University of California Press, Berkeley

Whalley J, Zhang S (2007) A numerical simulation analysis of (hukou) labour mobility restrictions in China. J Dev Econ 83:392–410. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2006.08.003

World Bank (2007) World development indicators 2007. Washington, DC

Wu X, Treiman DJ (2007) Inequality and equality under Chinese socialism: the hukou system and intergenerational occupational mobility. Am J Sociol 113:415–445. doi:10.1086/518905

Xue J, Zhong W (2006) Unemployment, poverty and income disparity in urban China. In: Shi L, Sato H (eds) Unemployment, inequality and poverty in urban China. Routledge, London and New York

Zhang KH, Song S (2003) Rural–urban migration and urbanization in China: evidence from time-series and cross-section analyses. China Econ Rev 14:386–400. doi:10.1016/j.chieco.2003.09.018

Zhang L, Huang J, Rozelle S (2002) Employment, emerging labor markets, and the role of education in rural China. China Econ Rev 13:313–328. doi:10.1016/S1043-951X(02)00075-5

Zhao Y (1999a) Labor migration and earnings differences: the case of rural China. Econ Dev Cult Change 47:767–782. doi:10.1086/452431

Zhao Y (1999b) Leaving the countryside: rural-to-urban migration decision in China. Am Econ Rev 89:281–286

Acknowledgements

The author thanks anonymous referees for their insightful comments on early drafts. Thanks are also due to many participants who commented on this paper in an annual conference of Theoretical Economics and Agriculture held in Utsunomiya, Japan. I also benefited greatly from discussion with Tomoo Higuchi and Takeshi Fujie. Funding from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science is acknowledged gratefully.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

The third to fifth columns of Appendix table show an example of the labor movements that would be induced by the removal of the hukou system. It is assumed that labor is so reallocated that Eqs. 7–12 may be met, through which no difference appears in the ex-post labor allocation (\( AL_{i}^{k} \)) across Cases I–III. Cases I and II cover all possible labor movements, while the labor movements take place only between agriculture and other sectors in Case III. Worthy of emphasis is the fact that there are infinite numbers of combination for the labor movements that satisfies Eqs. 7–12 when all possible labor movements are considered, suggesting that the system of equations presented in Sect. 3 cannot be solved uniquely. In contrast, the labor reallocation that satisfies Eqs. 7–12 is uniquely determined in Case III. It is for this reason that when building the theoretical model, we paid no attention to the labor reallocation between TVEs and urban informal sectors, and the inter-urban and inter-rural migration. Although this does not affect the simulation results, full information on a stream of labor across regions and sectors cannot be provided.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ito, J. The removal of institutional impediments to migration and its impact on employment, production and income distribution in China. Econ Change Restruct 41, 239–265 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10644-008-9051-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10644-008-9051-7