Abstract

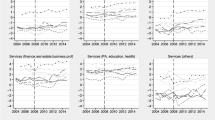

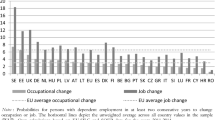

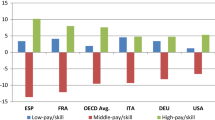

This article analyzes the occupational structure of 25 European Union countries during the period 2000–2004. Shift-share analyses are used to decompose cross-country differences in occupational structure into within sector and between sectors effects. The static analysis for 2004 shows that the new member countries employ a lower share of skilled workers because their industry structure is biased towards less skill-intensive industries and because they use fewer skills within industries. The differences in the shares of (high-skilled) non-production workers are dominated by the between (industrial) effect. In contrast, the dynamic analysis of 2000–2004 showed that changes in the share of high-skilled non-production workers are mostly driven by within sector changes, which are probably related to skill-biased technological change. Similar trends in the countries’ within effects support the catch-up of the new member countries’ skills demand, while the structural developments that could equalize the industry mix of the new and old member countries are related to increased domestic demand and will probably take time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

E.g. Autor et al. (1998), Morrison and Siegel (2001), Baltagi and Rich (2005) for the US, Berman et al. (1998) for the US, UK and selected developed countries, Gera et al. (2001) for Canada, Edwards (2004) for South Africa, Salvanes and Førre (2003) for Norway, Sakurai (2001) for Japan, Kelly (2007) for Australia.

Alternative measures of skills could be the wage bill share of non-production workers, the share of university degree workers or a codification of a special skill (e.g. cognitive) in a particular occupation. Despite minor differences between the occupational classifications used in different countries, the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO-88) is considered to be consistent across countries at the aggregated level (Elias and McNight 2001).

Many observations on implicit tax rates are lacking for the new member countries. The countries included in the NMS10 figures are the Czech Republic, Estonia, Lithuania and Slovakia. One should also notice that the tax bases could differ across countries.

The large growth of high-skilled non-production occupations in Italy is probably to a large extent due to a major revision in classifying workers into high-skill occupations in the Italian survey.

See Winchester et al. (2006) for a comparison of these two approaches and the implementation of cluster analysis to combine wage and educational information of occupational groups with the aim of deriving a composite measure of skills.

References

Autor DH, Katz LF, Krueger AB (1998) Computing inequality: have computers changed the labor market? Q J Econ 113:1169–1213

Baltagi BH, Rich DP (2006) Skill-biased technical change in US manufacturing: a general index approach. J Econom 126:549–570

Barrell R, Pain N (1997) Foreign direct investment, technological change, and economic growth within Europe. Econ J 107:1770–1786

Berman E, Bound J, Griliches Z (1994) Changes in the demand for skilled labor within U.S. manufacturing: evidence from the annual survey of manufacturers. Q J Econ 109:367–397

Berman E, Bound J, Machin S (1998) Implications of skill-biased technological change: international evidence. Q J Econ 113:1245–1279

Berman E, Machin S (2000) Skill-biased technology transfer around the world. Oxford Rev Econ Policy 16:12–22

Blanke J (2006) The Lisbon review 2006: measuring Europe’s progress in reform. World Economic Forum, Geneva. http://www.weforum.org/pdf/gcr/lisbonreview/report2006.pdf. Cited 5 Nov 2007

Briscoe G, Wilson R (2003) Modelling UK occupational employment. Int J Manpow 24:568–589

Caroli E, Van Reenen J (2001) Skill-biased organizational change? Evidence from a panel of British and French establishments. Q J Econ 116:1449–1492

Cörvers F, Dupuy A (2006) Explaining the occupational structure of Dutch sectors of industry, 1988–2003. ROA Working Paper No. 2006/7E. http://www.roa.unimaas.nl/pdf%20publications/2006/ROA-W-2006_7E.pdf. Cited 5 Nov 2007

Dekker R, de Grip A, Heijke H (1990) An explanation of the occupational structure of sectors of industry. Labour 4:3–31

Edwards L (2004) A firm level analysis of trade, technology and employment in South Africa. J Int Dev 16:45–61

Elias P, McNight A (2001) Skill measurement in official statistics: recent developments in the UK and the rest of Europe. Oxford Econ Papers 53:508–540

Esteban J (2000) Regional convergence in Europe and the industry mix: a shift-share analysis. Reg Sci Urban Econ 30:353–364

European Commission (2003a) Employment in Europe 2003—recent trends and prospects. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publication of the European Communities. http://ec.europa.eu/employment_social/employment_analysis/employ_2003_en.htm. Cited 5 Nov 2007

European Commission (2003b) The European Union labour force survey Methods and definitions—2001. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publication of the European Communities. http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/cache/ITY_OFFPUB/KS-BF-03-002/EN/KS-BF-03-002-EN.PDF. Cited 3 Jan 2008

European Commission (2005) Structures of the taxation systems in the European Union—data 1995–2003. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publication of the European Communities. http://epp.eurostat.cec.eu.int/cache/ITY_OFFPUB/KS-DU-05-001/EN/KS-DU-05-001-EN.PDF. Cited 5 Nov 2007

European Commission (2006) European union labour force survey quality report 2004. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publication of European Communities. http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/cache/ITY_OFFPUB/KS-CC-06-007/EN/KS-CC-06-007-EN.PDF. Cited 3 Jan 2008

Eurostat (2005) European Union foreign direct investment yearbook 2005—data 1998–2003. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publication of European Communities. http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/cache/ITY_OFFPUB/KS-BK-05-001/EN/KS-BK-05-001-EN.PDF. Cited 3 Jan 2008

Eurostat database (2007) Economy and finance: monthly labour costs. http://epp.eurostat.cec.eu.int. Cited 5 Nov 2007

Geishecker I (2006) Does outsourcing to central and eastern Europe really threaten manual workers’ jobs in Germany? World Econ 29:559–583

Gera S, Gu W, Lin Z (2001) Technology and the demand for skills in Canada: an industry-level analysis. Can J Econ 34:132–148

Kang S, Hong D-P (2002) Technological change and demand for skills in developing countries: an empirical investigation of the republic of Korea’s case. Dev Econ 40:188–207

Kelly R (2007) Changing skill intensity in Australian industry. Aust Econ Rev 40:62–79

Kijima Y (2006) Why did wage inequality increase? Evidence from urban India 1983–99. J Dev Econ 81:97–117

Leamer EE (1984) Sources of comparative advantage. Theory and evidence. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

Leamer EE (1992) Testing trade theory. NBER Working Paper No. 3957, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge MA. http://www.nber.org/papers/W3957. Cited 5 Nov 2007

Machin S, Van Reenen J (1998) Technology and changes in skill structure: evidence from seven OECD countries. Q J Econ 113:1215–1244

Minondo A, Rubert G (2006) The effect of outsourcing on the demand for skills in the Spanish manufacturing industry. Appl Econ Lett 13:599–604

Morrison P, Catherine J, Siegel DS (2001) The impact of technology, trade and outsourcing on employment and labor composition. Scand J Econ 103:241–264

Piva M, Santarelli E, Vivarelli M (2005) The skill bias effect of technological and organisational change: evidence and policy implications. Res Policy 34:141–157

Raiser M, Schaffer M, Schuchhardt J (2004) Benchmarking structural change in transition. Struct Change Econ Dyn 15:47–81

Sakurai K (2001) Biased technological change and japanese manufacturing employment. J Jpn Int Econ 15:298–322

Salvanes KG, Førre SE (2003) Effects on employment of trade and technical change: evidence from Norway. Economica 70:293–329

The Council of the European Union (1999) Council regulation No 126071999. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/site/en/oj/1999/l_161/l_16119990626en00010042.pdf. Cited 5 Nov 2007

Winchester N, Greenaway DR, Geoffrey V (2006) Skill classification and the effects of trade on wage inequality. Rev World Econ 142:287–306

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Karsten Staehr, Aurelijus Dabusinskas and Tiiu Paas for their helpful comments. We also benefited from comments by the participants of the scientific seminar at the University of Tartu Faculty of Economics and Business Administration on 25 Oct.2006, the CEDEFOP workshop “Anticipating Europe’s skill needs” at the University of Warwick on 2–3 Nov. 2006, the U-know project meeting at the University of Sussex on 7−10 Nov. 2006, and the annual meeting of the Estonian Economic Society in Pärnu on 12–13 Jan. 2007. Jaanika Meriküll acknowledges financial support from the grant of Jüri Sepp, RMJRISEPP and from the EU 6th framework project CIT5-CT-028519. The authors alone are responsible for the remaining errors and inconsistencies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A: ISCO classification at one-digit level (‘major groups’)

1.1 High-skilled non-production occupations

-

Isco 1

Legislators, senior officials and managers

-

Isco 2

Professionals

-

Isco 3

Technicians and associate professionals

1.2 Low-skilled non-production occupations

-

Isco 4

Clerks

-

Isco 5

Service workers and shop and market sales workers

1.3 Skilled production occupations

-

Isco 6

Skilled agricultural and fishery workers

-

Isco 7

Craft and related trades workers

-

Isco 8

Plant and machine operators and assemblers

1.4 Unskilled production occupations

-

Isco 9

Elementary occupations

1.5 Remaining occupations

-

Isco 0

Armed forces

-

Isco un

Occupational group unknown

Appendix B: NACE classification at one-digit level

-

a

Agriculture, hunting and forestry

-

b

Fishing

-

c

Mining and quarrying

-

d

Manufacturing

-

e

Electricity, gas and water supply

-

f

Construction

-

g

Wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles, motorcycles and personal and household goods

-

h

Hotels and restaurants

-

i

Transport, storage and communication

-

j

Financial intermediation

-

k

Real estate, renting and business activities

-

l

Public administration and defence; compulsory social security

-

m

Education

-

n

Health and social work

-

o

Other community, social and personal service activities

-

p

Private households with employed persons

-

q

Extra-territorial organizations and bodies

-

un

Sector unknown

Appendix C: Total differences in occupational shares between countries and EU averages

Appendix D: The industrial, within and interaction effects

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cörvers, F., Meriküll, J. Occupational structures across 25 EU countries: the importance of industry structure and technology in old and new EU countries. Econ Change 40, 327–359 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10644-008-9035-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10644-008-9035-7

Keywords

- Occupational structure

- Industry structure

- Technological change

- Technology diffusion

- Transition economies