Abstract

Introduced in 2012, China’s value-added tax (VAT) pilot program gradually replaced business tax (BT) with VAT. It has created a large fiscal squeeze for the local government since 75% of VAT revenue goes to the central government. Employing a difference-in-differences estimator with continuous treatment intensity, we find that this fiscal squeeze has a negative effect on pollution abatement expenditures. Moreover, private firms in eastern regions are less responsive to this shock than those in the rest of China due to having better regulated local governments. We also find that this effect is smaller in magnitude if the firm owner is younger, more educated or has industrial and political connections compared to her respective counterparts. This fiscal squeeze reduces pollution abatement expenditures more in regions with higher fiscal stress, looser environmental regulation, and lower pollution abatement costs. Further exploration shows that, in response to this fiscal squeeze, local governments have adopted several tools to compensate for revenue loss, including increasing tax enforcement and loosening environmental regulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

There are two reasons why the modern services sectors and the transportation sector were chosen to be part of the 3-year VAT pilot program. (1) Their businesses are more connected to manufacturing sectors, thus applying VAT to them is more urgent for the purpose of unifying tax rates between sectors. (2) This program was also initiated in several pilot regions first. Most firms in these pilot sectors are local enterprises without subsidiaries in other regions, and this transition did not cause an unequal tax burden between these subsidiaries.

Shanghai was enrolled in the program on January 1st, 2012. Beijing, Jiangsu, Anhui, Fujian, Guangdong, Tianjin, Zhejiang, and Hubei were enrolled between September and December, 2012. Since August 1st, 2013, the program has been nationwide for these selected modern services sectors and the transportation sector.

These two groups were merged into one institution in 2018.

As Chen (2017) documents, the effective rate of VAT in China is far below the statutory rate. This situation is caused by various issues, such as fake invoices and falsely high expenditures.

The survey years applied in our analysis are 2006, 2008, 2010, 2012, 2014, and 2016. They reflect firms’ characteristics in the previous year (2005, 2007, 2009, 2011, 2013, and 2015, respectively).

Instead of trimming the data, we also winsorize it and the results are similar.

For the pollution abatement expenditures variable, there are some zero-value observations. This situation could potentially lead to sample selection bias. In response, we conduct several tests in Sect. 5.1.4 below, and the results are robust.

Based on the outline of the gradual expansion, these affected sectors include the transport services sector, scientific research and polytechnic services sector, software and information technology services sector, cultural services sector, leasing services sector, postal services sector, and telecommunications sector.

Except Shanghai, implementation dates of all pilot regions are in the second half of the year. If the policy implementation date is too late in one region, the remaining days of that year are not enough for the program to take effect in that year.

Data on sector output in our study come from the China Economic Census Yearbook 2008, which is the nearest survey to the starting year of our sample. Specifically, for each year before 2014, the total output of affected sectors is constant. In 2014, several additional sectors are included into this pilot program (transport services sector, postal services sector, and telecommunications sector). As such, since 2015, the total output of affected sectors includes these additional sectors and thus increases. As a result, the variable “Output” varies in both city and time, and thus it cannot be absorbed by the city-level fixed effect.

The Pearson's correlation coefficient between the political indicator and the party indicator is 0.2208, indicating that they are not highly correlated. Based on our statistical summary, 38.6% of firm owners are members of the NPC or CPPCC, 36.7% of them are members of the Communist Party of China, and 19.4% of them are both. The former status can help build political connections with local government. This status can potentially bring indirect benefits for the firm and influence pollution abatement expenditures (Min et al. 2016). The latter status may increase the firm’s corporate social responsibility (CSR) and increase expenditures (Zhou et al. 2020).

0.2931 = 0.017/0.058, where the nominator is the coefficient of our estimate, and the denominator is the average pollution abatement expenditure before the expansion in our sample.

Eastern regions include Liaoning, Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Shandong, Jiangsu, Shanghai, Zhejiang, Fujian, Guangdong, and Hainan. Middle regions include Heilongjiang, Jilin, Shanxi, Henan, Anhui, Hunan, Hubei, and Jiangxi. Western regions include Inner Mongolia, Guangxi, Yunnan, Guizhou, Tibet, Xinjiang, Shaanxi, Ningxia, Qinghai, Sichuan, Chongqing, and Gansu.

http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2013-09/12/content_2486773.htm (in Chinese), accessed on August 9th, 2020.

The common measure of total factor productivity cannot be deducted in our sample due to missing fixed investments.

We thank the anonymous referee for this suggestion.

To be classified as a large enterprise, a firm needs to satisfy several criteria that are updated regularly: business revenue, the number of employees, and total capital.

To measure city-level tax enforcement, we follow the methodology in Mertens (2003), Xu et al. (2011). Tax enforcement equal to the actual tax ratio divided by the estimated tax ratio. The actual tax ratio is measured using the percentage of tax revenue to GDP. The estimated tax ratio is predicted using a multi-regression model where we regress the tax ratio on the first industry ratio (the first industry’s proportion to GDP), the second industry ratio (the second industry’s proportion to GDP), and municipal openness (the proportion of the sum of import and export to GDP). More details are available upon request.

In column (4), the dependent variable is turnover tax revenue (the natural logarithm of revenue from VAT and consumption tax). In column (5), the dependent variable is corporate income tax revenue (natural logarithm). Data from these two variables and all macroeconomic control variables come from China Statistical Yearbook for Regional Economy and China City Statistical Yearbook.

Similar as these categories of extrabudgetary revenue, the impact on fines is also small and insignificant. The reason for all insignificant impacts is because, in recent decades, the central government of China has made several official announcements to restrict the usage of extrabudgetary revenue. These announcements all aim to move extrabudgetary revenue into the budget and restrict the scope of administrative and institutional fees pertaining to firms:

(http://gz.mof.gov.cn/zt/banshizhinan/zhengcefagui/201012/t20101222_383174.htm; http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2014-06/26/content_8910.htm’; http://ln.mof.gov.cn/lanmudaohang/zhengcefagui/201609/t20160921_2423543.htm; all accessed on July 28, 2020).

References

Angrist JD, Pischke J-S (2014) Mastering’metrics: the path from cause to effect. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Bai J, Lu J, Li S (2019) Fiscal pressure, tax competition and environmental pollution. Environ Resource Econ 73(2):431–447

Banerjee A, Duflo E, Qian N (2020) On the road: access to transportation infrastructure and economic growth in China. J Dev Econ 145:102442

Cai H, Yuyu C, Qing G (2016) Polluting the neighbor: unintended consequences of china’s pollution reduction mandates. J Environ Econ Manag 76:86–104

Cao J, Qiu LD, Zhou M (2016) Who invests more in advanced abatement technology? Theory and evidence. Can J Econ Revue CanadienneD’ÉConomique 49(2):637–662

Chen SX (2017) The effect of a fiscal squeeze on tax enforcement: evidence from a natural experiment in China. J Public Econ 147:62–76

Cheng C-Y (2019) China’s economic development: growth and structural change. Routledge, Abingdon

Chow GC, Li K-W (2002) China’s economic growth: 1952–2010. Econ Dev Cult Change 51(1):247–256

Conrad K, Morrison CJ (1989) The impact of pollution abatement investment on productivity change: an empirical comparison of the US, Germany And Canada. Southern Econ J 55(3):684–698

Dang TV, Wang Y, Wang Z (2018) The Effects of Mandatory Pollution Abatement on Corporate Investment and Performance: Theory and Evidence from A US Regulation. Available at SSRN 3257675 (2018).

Di W (2007) Pollution abatement cost savings and FDI inflows to polluting sectors in China. Environ Dev Econ 12(6):775–798

Fang H, Bao Y, Zhang J (2017) Asymmetric reform bonus: the impact of VAT pilot expansion on China’s corporate total tax burden. China Econ Rev 46:S17–S34

Fowlie M (2010) Emissions trading, electricity restructuring, and investment in pollution abatement. Am Econ Rev 100(3):837–869

Hao Y, Deng Y, Lu Z-N, Chen H (2018) Is Environmental regulation effective in China? Evidence from city-level panel data. J Cleaner Prod 188:966–976

He G, Wang S, Zhang B (2020) Watering down environmental regulation in China. Q J Econ 135(4):2135–2185

Hoseini M, Briand O (2020) Production efficiency and self-enforcement in value-added tax: evidence from state-level reform in India. J Dev Econ 144:102462

Huiban JP, Mastromarco C, Musolesi A, Simioni M (2015) The impact of pollution abatement investments on technology: Porter hypothesis revisited. SEEDS Working Paper Series 8 (2015)

Keller W, Levinson A (2002) Pollution abatement costs and foreign direct investment inflows to US States. Rev Econ Stat 84(4):691–703

La F, Alberto Chong E, Duryea S (2012) Soap operas and fertility: evidence from Brazil. Am Econ J Appl Econ 4(4):1–31

Lee AI, Alm J (2004) The clean air act amendments and pollution abatement expenditure equipment. Land Econ 80(3):433–447

Li H, Zhou L-A (2005) Political turnover and economic performance: the incentive role of personnel control in China. J Public Econ 89(9–10):1743–1762

Li P, Lu Y, Wang J (2016) Does flattening government improve economic performance? Evidence from China. J Dev Econ 123:18–37

Liu Q, Lu Y (2015) Firm investment and exporting: evidence from China’s value-added tax reform. J Int Econ 97(2):392–403

Liu Y, Mao J (2019) How do tax incentives affect investment and productivity? Firm-level evidence from China. Am Econ J Econ Policy 11(3):261–291

Liu Y (2018) Government extraction and firm size: local officials’ responses to fiscal distress in China. J Comp Econ 46(4):1310–1331

López-Hernández AM, Zafra-Gómez JL, Plata-Díaz AM, de la Higuera-Molina EJ (2018) Modeling fiscal stress and contracting out in local government: the influence of time, financial condition, and the great recession. Am Rev Public Adm 48(6):565–583

Maisseu A, Voss A (1995) Energy, entropy and sustainable development. Int J Global Energy Issues 8(1–3):201–220

Mertens JB (2003) Measuring tax effort in central and Eastern Europe. Public Finance Manag 3(4):530

Maung M, Wilson C, Tang X (2016) Political connections and industrial pollution: evidence based on state ownership and environmental levies in China. J Bus Ethics 138(4):649–659

Moser P, Voena A (2012) Compulsory licensing: evidence from the trading with the enemy act. Am Econ Rev 102(1):396–427

Qi Y, Zhang L (2014) Local environmental enforcement constrained by central-local relations in China. Environ Policy Gov 24(3):216–232

Ren S, Li X, Yuan B, Li D, Chen X (2018) The effects of three types of environmental regulation on eco-efficiency: a cross-region analysis in China. J Clean Prod 173:245–255

Shadbegian RJ, Gray WB (2005) Pollution abatement expenditures and plant-level productivity: a production function approach. Ecol Econ 54(2–3):196–208

Stoerk T (2019) Effectiveness and Cost of Air Pollution Control in China. Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and The Environment

Wang H (2002) Pollution regulation and abatement efforts: evidence from China. Ecol Econ 41(1):85–94

Wang Q, Zhao Z, Shen N, Liu T (2015) Have Chinese cities achieved the win–win between environmental protection and economic development? From the perspective of environmental efficiency. EcolInd 51:151–158

Wu Y (2004) China’s economic growth: a miracle with Chinese characteristics, vol 6. Routledge, Abingdon

Wu J, Deng Y, Huang J, Morck R, Yeung B (2014) Incentives and outcomes: China’s environmental policy. Capital Soc 9(1):1–41

Xiao C (2020) Intergovernmental revenue relations, tax enforcement and tax shifting: evidence from China. Int Tax Public Finance 27(1):128–152

Xu W, Zeng Y, Zhang J (2011) Tax enforcement as a corporate governance mechanism: empirical evidence from China. Corp GovInt Rev 19(1):25–40

Zhang L, Chen Y, He Z (2018) The effect of investment tax incentives: evidence from China’s value-added tax reform. Int Tax Public Finance 25(4):913–945

Zhang D, Du W, Zhuge L, Tong Z, Freeman RB (2019) Do financial constraints curb firms’ efforts to control pollution? Evidence from Chinese manufacturing firms. J Clean Prod 215:1052–1058

Zhao X, Sun B (2016) The influence of Chinese environmental regulation on corporation innovation and competitiveness. J Clean Prod 112:1528–1536

Zhou P, Arndt F, Jiang K, Dai W (2020) Looking backward and forward: political links and environmental corporate social responsibility in China. J Bus Ethics 1–19

Zou J, Shen G, Gong Y (2019) The effect of value-added tax on leverage: evidence from China’s value-added tax reform. China Econ Rev 54:135–146

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 71803035; No. 71974051) and the key project of the National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 18ZDA064; No. 18ZDA097). We would like to thank the editor and three anonymous referees for their very helpful comments and suggestions. We also benefit from discussion with Huanxiu Guo and Lanlan Liu.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendices

1.1 Appendix A

The current study adopts two distinct measures of environmental regulation (ER). They are separately evaluated in columns (2) and (3) in Table 16. The first measure concerns three representative indicators of regulation: wastewater, sulfur dioxide, and dust (Zhao and Sun 2016; Ren et al. 2018). We standardize the original data on all three indicators since the raw data are not comparable. Then, the value of each single indicator is mapped into the interval [0, 1]. In this way, we remove the restriction of different units. The min–max normalization method is applied. We evaluate the ratio of each city’s level to the average level. If the ratio is larger than 1, then this city’s weighted average emissions of these three representative indicators are higher than the average of all cities, and the regulation in that city is also looser than average. Finally, this measure is adopted as its inverse value. Therefore, if fiscal squeeze indeed loosens environmental regulation as expected, we should see a negative coefficient for this measure. It is calculated as follows:

where \(UE_{ij}^{n} = \frac{{UE_{ij} - \min \left( {UE_{j} } \right)}}{{\max \left( {UE_{j} } \right) - \min \left( {UE_{j} } \right)}}\), and \(W_{j} = UE_{ij} /UE_{j}^{avg}\). \(UE_{ij}^{n}\) is the rescaled (min–max normalized) emission of pollutant j in city i during our sample period. \(\min \left( {UE_{j} } \right)\) and \({\text{max}}\left( {UE_{j} } \right)\), respectively, denote the minimum and maximum emissions of pollutant j of all cities in our sample. \(UE_{j}^{avg}\) denotes the average emissions of pollutant j in all cities. \(W_{j}\) represents the weight for each pollutant j.

The second measure of environmental regulation in our study focuses on the rates of abatement of sulfur dioxide and dust particles (Maisseu and Voss 1995). A higher rate of abatement indicates more stringent regulation in the city. We add the weight of each city, which is represented by the amount of emissions for each pollutant. This weighting is necessary because the amount of emissions varies greatly across cities, and the amount of emissions within each city also varies across different pollutants. If this measure of a city is higher, then we can conclude that firms in this city have, on average, a higher rate of abatement for the two representative indicators compared to other cities and are subject to a more stringent level of environmental regulation. If the fiscal squeeze indeed loosens environmental regulation as expected, we should also see a negative coefficient of this measure. It is calculated as follows:

where \(R_{ij}^{n} = \frac{{R_{ij} - {\text{min}}\left( {R_{j} } \right)}}{{\max \left( {R_{j} } \right) - {\text{min}}\left( {R_{j} } \right)}}\). \(R_{ij}^{n}\) is the rescaled (min–max normalized) rate of abatement of pollutant j (sulfur dioxide or dust particle) in city i during our sample period. \({\text{min}}\left( {R_{j} } \right)\) and \({\text{max}}\left( {R_{j} } \right)\), respectively, denote the minimum and maximum rates of abatement of pollutant j of all cities in our sample. \(P_{j}\) represents the weight for each pollutant j. Specifically, \(P_{j} = \frac{{D_{ij} }}{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i} D_{ij} }}/\frac{{GDP_{ij} }}{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i} GDP_{ij} }}\), where \(D_{ij}\) denotes the amount of emissions of pollutant j for city i. This weighting is necessary because the amount of emissions varies greatly across cities, and the amount of emissions within each city also varies across different pollutants.

1.2 Appendix B

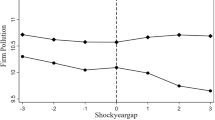

In this section, we provide graphical evidence showing that environmental regulation was loosened during our sample period. The following figure depicts that the ratio of environmental expenditures to total GDP has gradually decreased since 2012, indicating that environmental regulation has loosened in response to the fiscal squeeze (Qi and Zhang 2014; Bai et al. 2019; Hao et al. 2018) (Fig. 5).

1.3 Appendix C

In this section, we provide present descriptive statistics on several variables that are analyzed later in our paper (Table 17).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Peng, F., Peng, L., Mao, J. et al. The Short-Run Effect of a Local Fiscal Squeeze on Pollution Abatement Expenditures: Evidence from China’s VAT Pilot Program. Environ Resource Econ 78, 453–485 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-021-00539-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-021-00539-z