Abstract

Background

Primary care providers (PCPs) face increasing numbers of patients at risk for NAFLD and are responsible for the detection of NAFLD and the decision on referral to specialists. We conducted a PCP needs assessment to ascertain the barriers and desired supports for NAFLD in primary care.

Methods

We designed a cross-sectional study of PCPs at a large diverse health system and surveyed faculty, residents, and nurse practitioners. Questions assessed NAFLD knowledge, approach to diagnosis and fibrosis testing including use of FIB-4, and attitudes toward support tools.

Results

The survey was sent to 115 PCPs with an 80% (n = 92) response rate. Respondents were 52% faculty and 48% residents. Over 40% were unsure of which diagnostic tests to order and which data constituted a diagnosis. PCPs were aware of the importance of fibrosis, yet few knew the components of FIB-4, few used FIB-4 in practice, and yet the most common reason for referral was to obtain fibrosis staging. The majority showed high levels of interest toward possible tools to improve NAFLD management, and only 5% perceived lack of time to be a barrier.

Discussion

Our survey revealed PCPs need and want strategic approaches to NAFLD. We found PCPs lack confidence in diagnosing NAFLD and are inconsistent in management strategies. PCPs had high awareness of the importance of fibrosis, but not of the FIB-4. It was encouraging that PCPs reported that time was not a major barrier and had positive attitudes toward potential practice support tools, indicating that practice guidelines designed for primary care should be created.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The estimated US prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is 25% and rising, resulting in exponential increases in cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and liver-related deaths [1, 2]. NAFLD encompasses a range of severity from asymptomatic simple steatosis to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) to cirrhosis [3], and fibrosis stage is independently predictive of liver-related mortality [4,5,6]. Unfortunately, 25% of patients have a moderate or greater fibrosis stage at time of diagnosis [5]. Earlier detection of NAFLD would expand the time window for patients to seek treatment prior to fibrosis progression. Primary care providers (PCPs) encounter rising numbers of patients with NAFLD comorbidities [7], yet routine screening of at-risk patients in primary care is not currently recommended [8]. To improve accurate NAFLD diagnosis and appropriate specialty referral, an essential first step is understanding the barriers faced by PCPs. No prior study has evaluated the perspectives of PCPs around NAFLD detection and fibrosis staging. We conducted a PCP needs assessment survey and hypothesized that PCPs would have gaps in knowledge around NAFLD and low awareness and use of fibrosis testing, but high interest in receiving NAFLD guidance.

Methods

Study Population and Setting

We designed a cross-sectional study of PCPs at a single, large, urban primary care clinic with over 26,000 diverse patients and a multi-payer mix within a tertiary care academic health system. We categorized PCPs as faculty members or trainees. A faculty member was defined as a PCP who had completed their training, including those who were attending physicians, clinical fellows, and nurse practitioners. Faculty members were also grouped by their duration of clinical practice since residency. A trainee was defined as a PCP who was currently in their internal medicine residency. We surveyed only second- and third-year residents; first-year residents were not surveyed since they had not been in the PCP role for more than one month at the time of the survey. All faculty PCPs provide continuity of care to approximately 200 patients per half day of practice; all trainee PCPs cared for a total panel of approximately 120 patients. There are no systematic differences in the patients seen by PCPs or by trainees. All PCPs use the same clinic space and same EMR, have access to the same specialists, and use the same process for ordering services and referrals.

Survey Design and Methods

An electronic survey was sent to all PCPs in August 2020. After the initial survey was sent, electronic reminders were sent at 2 weeks and 4 weeks, and no incentives were offered or given for survey completion. The survey was closed after 4 weeks. All surveys returned were anonymous and were used for analysis. Responses were compiled using Qualtrics® software. The survey included multiple choice and Likert-scale questions. Multiple-choice questions specified whether the question allowed a single response or multiple responses. Questions assessed (1) knowledge of NAFLD prevalence and outcomes, (2) diagnostic and management practices, (3) approach to fibrosis testing including use of the FIB-4 noninvasive calculator, and (4) attitudes toward several hypothetical PCP practice support tools to assist with NAFLD. Data are reported as a percentage of responses for each category. For each NAFLD knowledge area, we compared the proportion of correct responses between faculty members and trainees using Chi-squared tests. All analyses were performed using Stata 16.0. This study was approved by the UCSF Institutional Review Board.

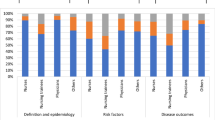

Results

The survey was sent to 115 providers with an 80% (n = 92) response rate. Table 1 shows characteristics of respondents (52% faculty and 48% trainees) and the categorization of faculty by years in practice. Faculty respondents consisted of 39 attending physicians, 1 general medicine fellow, 1 outpatient primary care chief resident, and 7 nurse practitioners. Table 2 shows responses to discrete knowledge questions by the proportion of correct responses for the overall sample and the comparison of trainee versus faculty responses. For the overall PCP population, the majority (67%) were incorrect and either under-estimated or were unaware of the prevalence of NAFLD, yet 79% correctly identified the long-term risks of NAFLD, including cardiovascular mortality, hepatocellular carcinoma, and the need for liver transplantation. Faculty PCPs were significantly more knowledgeable (84%) regarding the importance of fibrosis as the major predictor of cirrhosis compared to trainees (63%) but on other knowledge questions, there were no significant differences between groups. Figure 1 shows the perceptions of PCPs regarding barriers to NAFLD diagnosis, practices used in the management of a suspected NAFLD patient, and preferences for/against potential electronic medical record tools to help PCPs with NAFLD, for the overall sample and by faculty and trainees. Over 40% of PCPs were both unsure of which diagnostic tests to order and which data were sufficient to make the diagnosis. When managing suspected NAFLD, most PCPs reported repeating liver enzymes in 6 months (71%), counseling on lifestyle modification (82%), ordering viral hepatitis serologies (82%), and obtaining abdominal ultrasound (79%). Only 5% perceived lack of time to be a barrier in NAFLD management. Regarding the need for fibrosis assessments for NAFLD patients, while PCPs were knowledgeable about the importance of fibrosis (75%), only 25% knew the components of the noninvasive FIB-4 calculator, and only 15% reported using the FIB-4 in practice. However, the most common reason (95%) reported their reason for referring a patient to hepatology was for the purpose of obtaining fibrosis assessment either through Fibroscan® or biopsy. In addition, when asked about their interest in specific potential NAFLD tools to support their practice, high proportions of PCPs reported positively, including for an automated order set (76%), a link to a FIB-4 calculator (71%), and an electronic consult with decision support (56%).

Discussion

Despite the rapidly growing clinical research in the NAFLD field, and the frequent call for earlier recognition of patients before fibrosis progression, this is the first study assessing the practices and needs of PCPs in diagnosing, staging, and managing NAFLD. PCPs are on the front line of the NAFLD epidemic, and although there are PCP-oriented evidence-based guidelines in the management of conditions associated with NAFLD, such as diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, and cardiovascular disease, there have not been NAFLD screening or management guidelines designed for use by PCPs.

Our survey revealed PCPs, both faculty members and trainees, lack confidence in diagnosing NAFLD and demonstrate many inconsistencies with their approach to managing NAFLD. Most PCPs are taking multiple first-line steps to diagnose NAFLD, such as ordering viral hepatitis serologies and abdominal ultrasound, but vary widely in the frequency of ordering specialty referrals or advanced diagnostic testing. Our findings also tell us that PCPs need more education and experience with fibrosis tools that are available for their own use. There was a stark contrast between the high level of knowledge that fibrosis is the strongest predictor of cirrhosis, but low rates of PCPs performing fibrosis testing themselves. Use of the noninvasive FIB-4 calculator, requiring age, AST, ALT, and platelet count, would be a low-cost and convenient test that PCPs could perform and would help PCPs feel more confident regarding which patients need specialty referral, yet very few were familiar with the FIB-4 or were using it in practice. Though not statistically significant, it is notable that more current trainees were aware of the FIB-4 compared to faculty PCPs, suggesting that FIB-4 may be getting introduced in medical education.

It is encouraging that both trainee and faculty PCPs in this survey reported that lack of time was not a major barrier to NAFLD workups and indicated highly positive attitudes and levels of interest in proposed electronic practice support tools to make diagnosis and management more efficient. Our study is limited to a single center, so results cannot be generalized, but this primary care practice does provide more than half of the primary care visits for the largest academic health system in San Francisco.

In conclusion, in this first study of the PCP experience regarding NAFLD, it is clear that PCPs want and need clear NAFLD diagnostic strategies, clinical protocols, and noninvasive tools for fibrosis evaluation; it is therefore essential that primary care guidelines should be developed to improve early detection and interventions before disease progression.

References

Estes C, Razavi H, Loomba R, Younossi Z, Sanyal AJ. Modeling the epidemic of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease demonstrates an exponential increase in burden of disease. Hepatology. 2018;67:123–133. (Epub ahead of print). https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.29466.

Younossi Z, Anstee QM, Marietti M et al. Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15:11–20. (Epub ahead of print). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2017.109.

Matteoni CA, Younossi ZM, Gramlich T et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a spectrum of clinical and pathological severity. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:1413–1419. (Epub ahead of print). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-5085(99)70506-8.

Dulai PS, Singh S, Patel J et al. Increased risk of mortality by fibrosis stage in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2017;65:1557–1565. (Epub ahead of print). https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.29085.

Angulo P, Kleiner DE, Dam-Larsen S et al. Liver fibrosis, but no other histologic features, is associated with long-term outcomes of patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:389–397. (Epub ahead of print). https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.043.

Ekstedt M, Hagström H, Nasr P et al. Fibrosis stage is the strongest predictor for disease-specific mortality in NAFLD after up to 33 years of follow-up. Hepatology. 2015;61:1547–1554. (Epub ahead of print). https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.27368.

Ahmed MH, Abu EO, Byrne CD. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD): new challenge for general practitioners and important burden for health authorities? Prim Care Diabetes. 2010;4:129–137. (Epub ahead of print). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcd.2010.02.004.

Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE et al. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;67:328–357. (Epub ahead of print). https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.29367.

Funding

This work was supported by (1) Gilead Sciences, Inc. “NASH Models of Care” program, Grant # IN-US-989-5737 (R. Fox, D. Brandman). (2) The San Francisco Cancer Initiative (SF CAN), a collaborative community effort initiated by the UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center to reduce the cancer burden across San Francisco and beyond (www.sfcancer.org) (R. Fox). (3) National Research Service Award (NRSA) T32HP19025T-32 (J. Chu). The funders had no role in the analysis or interpretation of the data, the writing of the report, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RF wrote grant proposal, designed the survey, analyzed the data, designed tables and figures, and wrote the manuscript. KBI designed and administered the survey, collected and analyzed the data, created figures and tables, and wrote the manuscript. DB wrote grant proposal, designed the survey, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. JNC analyzed the data, performed statistics, and wrote the manuscript. MLG analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Dr. Brandman has received research support from Allergan, Conatus, and Grifols, and grant and research support from Gilead. She has served on an advisory board and consulted for Alnylam.

Ethical approval

This study was reviewed and approved by the UCSF Institutional Review Board.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Prior Presentations This work was presented as a poster at the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) The Liver Meeting, November 2021 and was awarded “Poster of Distinction”.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Islam, K.B., Brandman, D., Chu, J.N. et al. Primary Care Providers and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Needs Assessment Survey. Dig Dis Sci 68, 434–438 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-022-07706-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-022-07706-2