Abstract

Background

The gut hormones are important in regulating gastrointestinal motility. Disturbances in gastrointestinal motility have been reported in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Reduced endocrine cell density, as revealed by chromogranin A, has been reported in the colon of IBS patients.

Aims

To investigate a possible abnormality in the colonic endocrine cells of IBS patients.

Methods

A total of 41 patients with IBS according to Rome Criteria III and 20 controls were included in the study. Biopsies from the right and left colon were obtained from both patients and controls during colonoscopy. The biopsies were immunostained for serotonin, peptide YY (PYY), pancreatic polypeptide (PP), entroglucagon, and somatostatin cells. Cell densities were quantified by computerized image analysis.

Results

Serotonin and PYY cell densities were reduced in the colon of IBS patients. PP, entroglucagon, and somatostatin-immunoreactive cells were too few to enable reliable quantification.

Conclusion

The cause of these observations could be primary genetic defect(s), secondary to altered serotonin and/or PYY signaling systems and/or subclinical inflammation. Serotonin activates the submucosal sensory branch of the enteric nervous system and controls gastrointestinal motility and chloride secretion via interneurons and motor neurons. PYY stimulates absorption of water and electrolytes, and inhibits prostaglandin (PG) E2, and vasoactive intestinal peptide, which stimulates intestinal fluid secretion and is a major regulator of the “ileal brake”. Although the cause and effect relationship of these findings is difficult to elucidate, the abnormalities reported here might contribute to the symptoms associated with IBS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a gastrointestinal chronic disorder which is characterized by abdominal discomfort or pain associated with altered bowel habits, and often bloating and abdominal distension [1, 2]. The degree of symptoms varies in different patients from tolerable to severe, with a considerable reduction of quality of life and productivity [1–5]. This disorder affects 10–15% of the western population with female predominance [1, 2]. Besides the increased morbidity caused by IBS, it is an economic burden to society in different indirect forms, for example increased sick leave and over-consumption of healthcare resources [6, 7].

Disturbances of gastrointestinal motility have been reported in patients with IBS [8–14]. It has been speculated that this dysmotility is caused by genetic and psychosocial factors, and stress [6, 7]. The gastrointestinal tract hormones are important in regulating gastrointestinal motility [15]. Few studies have been conducted on gut hormones in IBS patients [16–23]. These studies concentrated mostly on serotonin [16–19].

In a previous study, the density of chromogranin A was reduced in the colon of patients with IBS [24]. Chromogranin A is a general marker for all endocrine cells. This finding raises the question as to which endocrine cell type is affected in the colon. Thus, this study was undertaken to discover the endocrine cell type(s) affected in the colon of IBS patients.

Materials and Methods

Patients and Controls

Forty-one patients with irritable bowel syndrome that fulfilled Rome Criteria III using the IBS module were included in the study [25, 26]. These patients were 39 females and two males with an average age of 35 years (range 18–58 years). Twenty-three patients had diarrhea (IBS-diarrhea) and 18 patients had constipation (IBS-constipation) as the predominant symptom. All patients underwent a complete physical examination and were investigated by means of blood tests (full blood count, electrolytes, calcium, and inflammatory markers), liver tests, and thyroid function tests.

Twenty subjects that underwent colonoscopy with biopsies were used as controls. Twelve of these subjects underwent colonoscopy because of gastrointestinal bleeding, where the source of bleeding was identified as hemorrhoids, and eight subjects because of health worries caused by a relative(s) having been diagnosed with colon carcinoma. These subjects were 13 females and seven males with an average age of 49 years (range 24–66 years).

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local Committee for Medical Research Ethics. All subjects gave oral and written consent.

Colonoscopy

Colonoscopy was performed on patients and controls, and two biopsies were taken from the cecum, from the ascending colon, and from the right half of the transverse colon. All six biopsies were pooled and used as the right colon. Moreover, two biopsies were taken from the left half of the transverse colon, from the descending colon, and from the sigmoid colon. These six biopsies were pooled and used as the left colon.

Histopathology and Immunohistochemistry

Biopsies were fixed overnight in 4% buffered paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 5-μm sections. The sections were stained with hematoxylin–eosin and immunostained by use of the avidin–biotin complex (ABC) method using the Vectastain ABC kit (Vector Laboratories) as described in detail elsewhere [27]. The primary antibodies used were: monoclonal mouse anti-serotonin (DakoCytomation, code no. 5HT-209), polyclonal anti-porcine peptide YY (PYY; Alpha-diagnostica, code PYY 11A), polyclonal rabbit anti-synthetic human pancreatic polypeptide (PP; Diagnostic Biosystems, code no. #114), polyclonal rabbit anti-porcine glicentin/glucagon (Acris Antibodies, code BP508), and polyclonal rabbit anti-synthetic human somatostatin (DakoCytomation, code no. A566). The antibodies were used at dilutions of 1:1,500, 1:1,000, 1:800, 1:400, and 1:200, respectively. The second layer biotinylated mouse anti-IgG and rabbit anti-IgG were obtained from DakoCytomation. Negative and positive controls were the same as those described elsewhere [27]. Anti-PYY cross-reacted <0.001% with neuropeptide Y (NPY) in the radioimmunoassay system.

Computerized Image Analysis

Numbers of immunoreactive cells and areas of the epithelial cells were measured by use of the Olympus software: Cell^D. The ×40 objective was used, so the frame (field) on the monitor represented an area of 0.14 mm2 of the tissue in each field. Each individual and peptide hormone was measured in 10 randomly chosen fields. Immunostained sections from IBS patients and controls were coded and mixed, and measurements were made without knowledge of the identity of the sections. The data from the fields were tabulated; the number of cells/mm2 of the epithelium was computed and statistically analyzed automatically.

Statistical Analysis

The Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric ANOVA test and Dunn`s post-test were used. P values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Endoscopy, Histopathology, and Immunohistochemistry

The colons of patients and control subjects were macroscopically normal.

Histopathological examination of the colon biopsies from patients and controls revealed normal histology, except for four controls and five patients, where nonspecific inflammation was found. In the colon of patients and control subjects, serotonin, PYY, PP, entroglucagon, and somatostatin-immunoreactive cells were found, mostly in the upper part of the crypts of Lieberkühn. These cells were basket or flask-shaped (Figs. 1, 2).

Computerized Image Analysis

PP, entroglucagon, and somatostatin-immunoreactive cells were too few in the biopsy material examined. This made it difficult to quantify these cell types reliably.

There was no statistically significant difference between the right and left colon in controls regarding densities of serotonin and PYY-immunoreactive cells (P = 0.9 and 0.1, respectively).

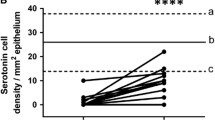

Serotonin cell density was reduced in the colon of IBS patients (Figs. 1, 3). This reduction was found in both IBS-diarrhea and IBS-constipation patients. In the right colon, serotonin cell density in IBS patients as a whole and in both sub-types was lower than in controls (Fig. 3). In the left colon, serotonin cell density was reduced in IBS patients as a whole and in IBS-diarrhea patients, but not in those with IBS-constipation (Fig. 3).

PYY cell density was lower than controls in the colon as a whole and in the right and left colon. PYY cell density was reduced also in both sub-types of IBS (Figs. 2, 4).

PYY cell density in the colon in IBS patients and as a whole and in the two subtypes of IBS (a), in the right colon (b), and in the left colon (c). Statistical significance expressed as in Fig. 3

Discussion

The age and sex of the patients and control subjects used in this investigation did not match completely. The control subjects are slightly older and the proportion of males to females is higher. In previous studies, however, age and gender have been found to have no effect on the density of intestinal endocrine cells in adults [28, 29]. Different topographic distribution of large intestinal endocrine cell densities has previously been reported [30]. Thus, in this investigation endocrine cell densities were studied in different segments of the colon.

This study showed that serotonin and PYY cell densities were reduced in both sub-types of IBS, i.e. IBS-diarrhea and IBS-constipation. It is noteworthy, however, that in the left colon of patients with IBS-constipation, serotonin cell density was not statistically significant. One cannot exclude the possibility this was a type II statistical error; however, in a previous report chromogranin A cell density was also not significant in the same segment of the colon of the same patient group [24]. Mucosal 5-HT concentration has been reported to be low in IBS patients [31], in agreement with our observation. Previous studies of patients with post-infectious IBS (PI-IBS) of the diarrhea-predominant type have shown however, that the number of serotonin cells increased in the rectum [16, 19, 32, 33]. Our finding that serotonin cell density was reduced in the colon raises the possibility that PI-IBS and sporadic IBS can have a different pathophysiology. One should also point out that the rectum harbors a larger number of endocrine cells than the colon [30].

The low densities of serotonin and PYY cells in IBS patients found here could be primary or secondary to other pathological process. Thus, the cause of these observations could be primary genetic defect(s), secondary to altered serotonin and/or PYY signaling systems and/or subclinical inflammation. It is not known whether a defect occurs in the genes controlling the expression of serotonin and PYY. However, an association between a functional polymorphism in the serotonin transporter (SERT) gene and diarrhea-predominant IBS has been reported [34, 35]. Furthermore, it has been reported that tryptophan hydroxylase 1 messenger RNA, serotonin transport messenger RNA, and serotonin transport immunoreactivity all are reduced in IBS patients [31]. It is possible that the observation made here on serotonin is secondary to SERT gene polymorphism and/or an altered 5-HT signaling system. It has been proposed that low-grade inflammation might be responsible for symptoms in at least a subset of IBS sufferers [36, 37]. It is possible that the abnormality observed here is caused by a colonic submucosal low-grade inflammation. In support of this assumption is the observation that serotonin secretion by enterochromaffin (EC) cells can be enhanced or attenuated by secretory products of immune cells, for example CD4+T [38]. Furthermore, serotonin modulates the immune response [38]. The EC cells are in contact with or very close to CD3+ and CD20+ lymphocytes and several sertotongeric receptors have been characterized in lymphocytes, monocytes, macrophages, and dendrtic cells [38, 39]. It has been reported that IBS-diarrhea patients have a significantly higher prevalence of macroscopic mucosal colonic erythema, with “nonspecific” inflammation being observed for a significant proportion of these patients on histopathological evaluation [35]. The authors argued, however, that their findings might be explained by an ascertainment bias [35]. The occurrence of colonic mucosal nonspecific inflammation in the IBS patients investigated in this study did not differ from that of healthy controls.

It is rather interesting that patients with IBS sub-types had the same abnormalities in serotonin and PYY cells. Previous studies have shown that IBS-diarrhea and IBS-constipation have the same abnormality in the serotonin signaling system [31]. Actually, IBS patients are characterized basically by altered bowel habits. Dividing IBS patients into subtypes based on predominance of diarrhea or constipation is a clinical classification to facilitate clinical symptomatic management. It is possible, therefore, that IBS patients, irrespective of subtype, share the same pathophysiology.

Serotonin activates the submucosal sensory branch of the enteric nervous system and controls gastrointestinal motility and chloride secretion via interneurons and motor neurons [40, 41]. PYY stimulates absorption of water and electrolytes and is a major regulator of the “ileal brake” [42]. Furthermore, PYY inhibits prostaglandin (PG) E2 and vasoactive intestinal peptide, which stimulate intestinal fluid secretion [43–45]. Administration of PYY inhibits diarrhea in experimental mouse models by reducing intestinal fluid secretion and slowing colonic transit [46]. Although the cause and effect relationship of our findings is difficult to elucidate, the abnormalities reported here might contributes to the symptoms associated with IBS.

References

Thompson WG. A world view of IBS. In Camilleri M, Spiller R, eds. Irritable bowel syndrome: diagnosis and treatment. Philadelphia and London: Saunders; 2002:17–26.

Drossman DA, Li Z, Andruzzi E, et al. U.S. householder survey of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Prevalence, sociodemography, and health impact. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1569–1580.

Hugin AP, Whonwell PJ, Tack J, Mearin F. The prevalence, patterns and impact of irritable bowel syndrome: an international survey of 40, 000 subjects. Alment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:643–650.

Wilson S, Roberts L, Roalfe A, Bridge P, Sukhdev S. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome: a community survey. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54:495–502.

Whitehead WE, Burnett CK, Cook EW, III, Taub E. Impact of irritable bowel syndrome on quality of life. Dig Dis Sci 1996; 41: 2248–2253.

Everhart JE, Renault PF. Irritable bowel syndrome in office-based practice in the United States. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:998–1005.

Harvey RF, Salih SY, Read AE. Organic and functional disorders in 2000 gastroenterology outpatients. Lancet. 1983;1:632–634.

Whorwell PJ, Clouter C, Smith CL. Oesophagus motility in the irritable bowel syndrome. BMJ. 1981;282:1101–1102.

Caballero-Plasencia AM, Valenzula-Barranco M, Herrerias-Gutierrez JM, et al. Altered gastric emptying in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Eur Nul Med. 1999;26:404–409.

Evans PR, Bak YT, Shuter B, et al. Gastroparesis and small bowel dysmotility in irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:2087–2093.

van Wijk HJ, Smout AJ, Akkerman LM, et al. Gastric emptying and dyspeptic symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1992;27:99–102.

Cann PA, Read NW, Brown C, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome: relation of disorders in the transit of single solid meal top symptom patterns. Gut. 1983;24:405–411.

Kellow JE, Philips SF. Altered small bowel motility in irritable bowel syndrome is correlated with symptoms. Gastroenterology. 1987;92:1885–1893.

Kellow JE, Philips SF, Miller LJ, et al. Dysmotility of the small bowel in irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 1988;29:1236–1243.

El-Salhy M. Gut neuroendocrine system in diabetes gastroenteropathy: possible role in pathophysiology and clinical implications. In Ford AM, ed. Focus on diabetes mellitus research. New York: Nova Science Publishers; 2006:79–102.

Lee KJ, Kim YB, Kwon HC, Kim DK, Cho SW. The alteration of enterochromaffin cell, mast cell and lamnia propria T lymphocyte numbers in irritable bowel syndrome and its relationship with psychological factors. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1689–1694.

Wang SH, Dong L, Luo JY, et al. Decreased expression of serotonin in the jejenum and increased numbers of mast cells in the terminal ileum in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:6041–6047.

Spiller RC, Jenkins D, Thornley JP, et al. Increased rectal mucosal enteroendocrine cells, T lymphocytes, and increased gut permeability following acute Campylobacter enteritis and in post-dysenteric irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2000;47:811–904.

Dunlop SP, Jenkins D, Neal KR, Spiller RC. Relative importance of enterochromaffin cell hyperplasia, anxiety, and depression in postinfectious IBS. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1651–1659.

Park JH, Rhee P-L, Kim G, et al. Enteroendocrine cell counts correlated with visceral hypersensitivity in patients with diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18:539–546.

Van Der Veek PP, Biemond I, Masclee AA. Proximal and distal gut hormone secretion in irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:170–177.

Dizdar V, Spiller R, Hanevik K, Gilja OH, El-Salhy M, Hausken T. Relative importance of CCK (cholecystokinin) and 5-HT (serotonin) in Giardia-induced Post-infectious IBS. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:883–891.

El-Salhy M, Vaali K, Dizdar V, Hausken T (2010) Abnormal small intestinal endocrine cells in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Dig. Dig. Sci. (Epub ahead of print). doi:10.1007/s10620-010-1169-6.

El-Salhy M, Lomholt-Beck B, Hausken T (2010) Chromogranin as a tool in the diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol. (Epub ahead of print). doi:10.3109/00365521.2010.503965.

Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, et al. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480–1491.

El-Salhy M, Stenling R, Grimelius L. Peptidergic innervation and endocrine cells in the human liver. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1993;28:809–815.

Sandström O, El-Salhy M. Aging and endocrine cells of human duodenum. Mech Ageing Develop. 1999;108:39–48.

Sandström O, El-Salhy M. Human rectal endocrine cells and aging. Mech Ageing Develop. 1999;108:219–226.

Sjölund K, Sandèn G, Håkanson R, Sundler F. Endocrine cells in human intestine: an immunocytochemical study. Gastroenterology. 1983;85:1120–1130.

Coates MD, Mahoney CR, Linden DR, et al. Molecular defects in mucosal serotonin content and decreased serotonin reuptake transporter in ulcerative colitis and irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1657–1664.

Spiller RC, Jenkins D, Thornely JP, et al. Increased rectal mucosal enteroendocrine cells, T lymphocytes, and increased gut permeability following acute Camylobacter enteritis and in post-dysentric irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2000;47:804–811.

Lee HS, Lim JH, Park H, Lee SI. Increased immunoreactive cells in intestinal mucosa of postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome patients 3 years after acute Shigella infection-an observation in a small case control study. Yonsei Med J. 2009;51:45–51.

Camilleri M. Is there a SERT-ain association with IBS. Gut. 2004;53:1396–1398.

Yeo A, Boyd P, Lumsden S, et al. Association between a functional polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene and diarrhoea predominant irritable bowel syndrome in women. Gut. 2004;53:1452–1458.

Chey D, Nojkov B, Rubenstein JH, Dobhan RR, Greensen JK, Cash BD. The yield of colonoscopy in patients with non-constipated irritable bowel syndrome: results from a prospective, controlled US trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:859–865.

Spiller R. Serotonin, inflammation, and IBS: fitting the jigsaw together? Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2007;45: S115–S119.

Khan WI, Ghia JE. Gut hormones: emerging role in immune activation and inflammation. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;161:19–27.

Yang GB, Lackner AA. Proximity between 5HT secreting enteroendocrine cells and lymphocytes in the gut mucosa of rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) is suggesting a role for entrochromaffin cell 5-HT in mucosal immunity. J Neuroimmunol. 2004;146:46–49.

Gershon MD. Plasticity of serotonin control mechanisms in the gut. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2003;3:600–607.

Kelum J, Albuqeque FC, Stoner MC, Harris RP. Stroking human jejunal mucosa induces 5-HT release an Cl-secretion via afferent neurons an 5-HT4 receptor. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:G515–G520.

Walsh JH. Gastrointestinal hormones. In: Johanson LR, ed. Physiology of the gastrointestinal tract, 3rd edn. New York: Raven Press; 1994:1–128.

Goumain M, Voisin T, Lorinet AM, et al. The peptide YY-preferring receptor mediating inhibition of small intestinal secretion is a peripheral Y(2) receptor: pharmacological evidence and molecular cloning. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;60:124–134.

Souli A, Chariot J, Voisin T, et al. Several receptors mediate the antisecretory effect of peptide YY, neuropeptide YY, and pancreatic polypeptide on VIP-induced fluid secretion in the rat jejenum in vivo. Peptides. 1997;18:551–557.

Whang EE, Hines OJ, Reeve JR, et al. Anti-secretory mechanisms of peptide YY in rat distal colon. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:1121–1127.

Moriya R, Shirakura T, Hirose H, Kanno T, Suzuki J, Kanatani A. NPY Y2 receptor agonist PYY (3–36) inhibits diarrhea by reducing intestinal fluid secretion and slowing colonic transit in mice. Peptides. 2010;31:671–675.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the nurses at the endoscopy unit, Stord Hospital: Eli Lillebø, Astrid Reinemo, and Lillian Salmelid for their enthusiasm and for assisting with gastroscopy and colonoscopy, and collecting the biopsies. Thanks are due to Åsa Helene Lundal at the Department of Pathology, Haugesund hospital, for co-ordination of the collaboration between Stord and Haugesund hospitals. We would like to express our gratitude to Professor Hans Olav Fadnes, head of the Department of Medicine, Stord Helse-Fonna Hospital, for his support and for reading the manuscript. This study was supported by a grant from Helse-Fonna.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

El-Salhy, M., Gundersen, D., Østgaard, H. et al. Low Densities of Serotonin and Peptide YY Cells in the Colon of Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Dig Dis Sci 57, 873–878 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-011-1948-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-011-1948-8