Abstract

The Anti-Money Laundering regime has been important in harmonizing laws and institutions, and has received global political support. Yet there has been minimal effort at evaluation of how well any AML intervention does in achieving its goals. There are no credible estimates either of the total amount laundered (globally or nationally) nor of most of the specific serious harms that AML aims to avert. Consequently, reduction of these is not a plausible outcome measure. There have been few efforts by country evaluators in the FATF Mutual Evaluation Reports (MERs) to acquire qualitative data or seriously analyze either quantitative or qualitative data. We find that data are relatively unimportant in policy development and implementation. Moreover, the long gaps of about 8 years between evaluations mean that widely used ‘country risk’ models for AML are forced still to rely largely on the 3rd Round evaluations whose use of data was minimal and inconsistent. While the 4th round MERs (2014–2022) have made an effort to be more systematic in the collection and analysis of data, FATF has still not established procedures that provide sufficiently informative evaluations. Our analysis of five recent National Risk Assessments (a major component of the new evaluations) in major countries shows little use of data, though the UK is notably better than the others. In the absence of more consistent and systematic data analysis, claims that countries have less or more effective systems will be open to allegations of ad hoc, impressionistic or politicized judgments. This reduces their perceived legitimacy, though this does not mean that the AML efforts and the evaluation processes themselves have no effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the mid-1980s first the US and then the UK criminalized drugs money laundering. Since then the world has witnessed an extraordinary growth in legislative and institutional efforts to establish processes to properly identify financial services customers, to require private sector institutions to report suspicions of their customers, and to freeze and confiscate the proceeds of crime nationally and transnationally. There have also been very uneven efforts in different countries to sanction some major and minor financial and professional intermediaries – using criminal, civil and regulatory powers – and some serious ‘primary offenders’ via money laundering charges. These international actions clash with the broader effort to facilitate money flows via the liberalization of currency restrictions and of trade flows globally, which goes under the general rubric of neo-liberalism.

Central to this effort is the Financial Action Task Force (FATF). As of April 2017, FATF had 35 national and two regional members: this includes the major economic actors from each continent. Another 180 countries currently are members of nine FATF-Style Regional Bodies (FSRBs) who represent them at three times per year FATF plenaries. The IMF and World Bank have observer status on FATF, retaining their independence. They also play a significant role in evaluations and in Technical Assistance to nations to help in meeting the standards (Nance, this volume). The efforts of the Anti-Money Laundering movement to roll back economic deregulation have been described by several government officials as combating ‘the dark side of globalization’. The global AML effort aims to persuade or coerce financial institutions (broadly defined) and other key ‘enablers’ to assume responsibility for policing attempts to use the financial system for either criminal or terrorist purposes. Coverage of the professions has been very uneven: for example, outside the UK [1], lawyers have been comparatively successful in resisting pressures to collaborate. National governments and firms in the regulated sector vary in the degree to which they support this effort, but FATF has effective coercive tools to enhance their laws and institutions [2].

The AML regime, for better or for worse, is a major intrusion into the financial system of all nations. It directly affects individuals who are identified as at high risk of violating the rules (for example the 1036 pages [as of May 1, 2017] of the US Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List - https://www.treasury.gov/ofac/downloads/sdnlist.pdf - which includes suspected terrorists). For these individuals and firms, the listing can have serious adverse consequences, which is socially as well as personally harmful if they are in fact innocent of ML/TF intent or if individuals are mistaken for those who are properly listedFootnote 1.Footnote 2 Indirectly, through the creation of additional and costly steps in financial transactions, AML affects much of the population both in the developed and the developing world. Developing countries are affected in addition through another distinct set of mechanisms - such as international banks refusing to accept (a) their local banks as correspondent banks and (b) money-service businesses serving them as their clients, though it remains unclear just how substantial those effects are [3, 4].

Like many changes in the area of crime control, the AML initiatives were not developed alongside any measures of effectiveness or even efficiency. Fighting global bads was a good in itself, and detailed evidence of the composition of harms and the impact of control efforts was not central to the political acceptance of the need for action. Thirteen years after the FATF’s creation, the designers of the 2002 FATF Recommendations were instructed not to pay attention to the costs of the system, direct or indirect (personal communication). It was, and to a large extent still is, taken for granted that actions taken against money laundering and especially the financing of terrorism will have a positive welfare impact, both gross and net of costs.

The role of data in ‘the AML movement’ may be seen at several levels. At the highest level, data about illicit flows and the national/global ‘bads’ allegedly emanating from them or at least made easier by them are part of the claims-making process about the extent and content of ‘the problem’, required to get media and political attention. Thus, the release of the “Panama Papers” in May 2016 [5] led to yet more calls from political figures such as the then British Prime Minister (David Cameron) for further efforts to prevent what was seen as money laundering for purposes of tax evasion and Grand Corruption. However, it was the range and scale of celebrity examples rather than data per se that drove the media attention and the scandals; the size of the Russian cellist’s offshore account juxtaposed with his close friendship with President Putin attracted particular attention (outside Russia), but the reverberations for politicians in many countries (e.g. Iceland and Pakistan) were significant.

The absence of critical media and political attention to any particular set of data, and the failure to utilize them as more than a rhetorical tool of ‘shroud waving’ is an interesting sociocultural phenomenon in itself. However, the national/global ‘goods’ flowing from control are represented more by cases and anecdotes than by effectiveness data. This is illustrated by the press releases by US agencies such as FinCEN, DEA, IRS, ICE, FBI, and Department of JusticeFootnote 3 and – to a lesser extent – their equivalents elsewhere, which give examples of ‘bads’ attacked as a result of their efforts, aimed both at public legitimation and inter-agency/funding justification. At operational levels, data are collected for both strategic and tactical/investigative purposes, most commonly the latter. This includes collating and accessing automated financial flow and other dataveillance technology, working on the principle of draining the swamp to catch the snake – “[w]hile we’ll try to find every snake in the swamp, the essence of the strategy is draining the swamp”.Footnote 4 Countries such as Australia, Canada and the U.S. that aim to collect data on all wire transfers, et cetera, can do sophisticated analysis on the data they have, and the U.S. has increasingly used Geographic Targeted Orders as a form of data collection for Problem Oriented Policing. Other countries simply deal with the problems in front of them.

Evaluation is a touchstone of contemporary policy making; good policy requires systematic and transparent evaluation. AML is just the kind of broad policy intervention that requires evaluation to improve its design and operation, if not to justify its existence. Despite the publication of national Mutual Evaluation Reports (MERs) and, more recently, National Risk Assessments, the fact is that there has been minimal effort at AML evaluation, at least in the sense in which evaluation is generally understood by public policy and social science researchers, namely how well an intervention does in achieving its goals.

Much of the problem lies in the nature of data that are available, what is used and how it is analyzed. Evaluation requires data and nowadays, it is generally quantitative, supplemented by an understanding of how the data are created and how they are processed. For AML, relevant quantitative data on serious crimes for gain is rare, though administrative and criminal justice data on AML processing have improved over time. The ideal evaluation would take some measure of the target activity, such as the total amount of money laundered, and estimate how much that has been reduced by the imposition of AML controls. However, as frequently repeated in MERs and other documents,Footnote 5 there are no credible estimates of the total amount laundered, either globally or nationally, as discussed in Section 2. Nor are there any clear international or even national measures of most of the harms that AML aims to avert, such as frauds or drugs/human trafficking. The ultimate targets of FATF itself, as articulated in its 2012 Goals and Objectives appear to be to strengthen financial sector integrity and to contribute to safety and security (i.e. to reduce the harms from crime and terrorism),Footnote 6 but these are goals on which progress is hard to assess. In the aftermath of the global financial crisis, the idea that AML measures have made an important contribution to financial integrity is hard to sustain: indeed, AML regulations may make bribery of bankers more rather than less likely, to induce them to evade the controls.Footnote 7 Thus qualitative data are essential, along with a systematic framework for analysis of such data. AML evaluators seek increasingly to acquire such data, but measuring interventions against levels and organization of serious crimes require data that are possessed by very few countries [7,8,9]. Additionally, evaluation teams vary in their capacity to analyze what little data they usually are able to obtain.

This paper will review the role of data in the evaluation of the system, particularly the MERs. We examine only the AML efforts, not those related to terrorism finance, simply because (like the FATF and FSRB assessors) we have so little access to the data used to make judgments about the adequacy of existing control efforts. We conclude that data are relatively unimportant in policy creation and sustenance. In fact, Halliday (2017, unpublished) argues that global regulation of AML relies less on data and more often on plausible folk theories. For MERs, the system has recently made an effort to be more systematic in the collection and analysis of data but still has not established procedures that provide informative evaluations.

Section 2 is a detailed analysis of the limits of efforts to estimate the Proceeds of Crime. Section 3 describes how data were used in some of the major elements of the third round of Mutual Evaluation Reports from 2004 to 2012. In Section 4 we consider the early stages of the fourth round of evaluations, focusing on the National Risk Assessments that are an important element of these new MERs. Section 5 consists of concluding comments.

How much money is laundered?

The amount of money laundering that occurs depends on whether one adopts a narrow definition that accords with the public image, namely active attempts to disguise the criminal origins of savings, or a broader definition (that is becoming more common legally) applying to everything criminals do with the proceeds of a crime. The latter makes money-laundering co-extensive with the proceeds of crimes globally; the former (which we favor, though it is more difficult in practice) measures a more active process of saving and hiding crime proceeds. There continues to be active dispute over the proper denotation of the concept.Footnote 8

As already noted, data on scale have played a modest role in the need to show that something is being done about money laundering and the financing of terrorism. Nevertheless, a modern problem requires estimation of its scale, so that it can be compared to other problems for prioritization of public resources, and so that performance measures can be developed against which to judge the efforts of those who aim to combat it. Thus, there has been a modest line of efforts to develop estimates of money laundering at the national and global levels; see [11], Chapter 2, for a review. More recently, Walker and Unger [12] have made some highly questionable high-end guesstimates based on heroic assumptions and extrapolations (developed further in [13]). Antonio Maria Costa, head of the UN Office on Drugs and Crime, in 2009 during the Great Recession, ‘said he has seen evidence that the proceeds of organized crime were "the only liquid investment capital" available to some banks on the brink of collapse…. He said that a majority of the $352bn (£216bn) of drugs profits was absorbed into the economic system as a result’.Footnote 9 Unfortunately, this statement contains no tested or testable evidence, so for the rest of us, it is a matter of faith or disbelief.

There are weak foundations for the UNODC [14] report that criminals, especially drug traffickers, ‘may have laundered’ around $1.6 trillion, or 2.7% of global GDP, in 2009.Footnote 10 This figure, it states, is consistent with the 2 to 5% range previously established (sic!) by the International Monetary Fund to estimate the scale of money-laundering, which itself – unmentioned in any official accounts - was based on the slightest of efforts made by others.Footnote 11 More plausibly, UNODC noted that less than 1% of global illicit financial flows is currently being seized and frozen, a proportion that is unlikely to have risen much since. This raises for us the problem that if 99% of illicit flows (turnover or profits) annually are not confiscated, the cumulative volume of illicit assets must be very high indeed. The UNODC report ‘estimates’ that the total amount of criminal proceeds generated in 2009, excluding those derived from tax evasion, may have been approximately $2.1 trillion, or 3.6% of global GDP in that year (2.3 to 5.5%). Of that total, the proceeds of transnational organized crime - such as drug trafficking, counterfeiting, human trafficking and small arms smuggling – ‘may have amounted to 1.5 per cent of global GDP, and 70 per cent of those proceeds are likely to have been laundered through the financial system’. The illicit drug trade - accounting for half of all proceeds of transnational organized crime and a fifth of all crime proceeds - is stated to be the most profitable sector. Traffickers’ gross profits from the cocaine trade were estimated at $84 billion in 2009, and the study asserted that roughly two thirds may have been laundered. Most profits from the cocaine trade are laundered in North America and in Europe, whereas illicit income from other sub-regions is probably laundered in the Caribbean. None of these figures has a provenance that bears scrutiny and the drug figures are considerably higher than estimates from the United States that do have a well-established provenance [16].Footnote 12

Anticorruption NGOs such as Global Financial Integrity publish large ‘estimates’ of illicit financial flows, which have not so far received the critical attention that they merit (see [17] and essays in [18]). However there is a sense in which these ‘data’ are merely advocacy claims for attention to particular problems: no-one takes them very seriously as baselines for evaluating policy effectiveness, except to suggest that there is a need to do more.Footnote 13 Conversations in professional circles suggest that liberal/leftist skeptics stay away from critiquing claims about Grand Corruption and corporate tax fraud revenues because of the desire not to undermine the fight against these excoriated activities.

However, it is not clear that it is either useful or feasible to estimate the extent of either dirty money or the scope of money-laundering (see [20] and contributions to [18]). Numbers are frequently cited, with minimal documentation, becoming “facts by repetition.” For example, on the basis of very modest evidence, as already noted, the IMF estimated a total of $590 billion to $1.5 trillion globally in 1996 [21]. In 2005 the United Nations cited the range of $500 billion to $1 trillion (http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/money_laundering.html, accessed June 2, 2005). Such figures increase over time but unlike crime rates, never appear to fall (see, for example, [14]), only partly because an increasing number of predicate crimes (such as Grand Corruption and tax evasion) – i.e. crimes that give rise to proceeds that are concealed or otherwise dealt with - are added to them. A sustained effort between 1996 and 2000 by the FATF to produce a fully documented estimate failed both for conceptual reasons (what is money laundering?) and empirical problems (what data could be relied on?). There are, however, a few estimates of the potential demand for money laundering (criminal revenues) that are regularly treated as actual money-laundering estimates, without for example deducting business or lifestyle expenditures [22, 23].Footnote 14

A RAND study suggested that 2005 Mexican Drug Trafficking Organizations’ gross revenues (significantly more than their net profits) from moving drugs into the United States total $5.1 billion ([27], p. 30), plus relatively modest further income in the low hundreds of millions from people trafficking.Footnote 15 Even taken at face value, however, these numbers are only weakly related to money laundering. Fearsome though they may be, Mexican DTOs have large expenses in bribes to law enforcement and politicians (which may have to be laundered only when they are above a rather high threshold of lifestyle and patronage expenditures); and they have large levels of ‘staffing’ to support, mainly in cash from cash proceeds of crimes. The near dollarization of Mexico means that they do not even have currency conversion problems.

In addition to such organized criminal activity, much income from selling drugs is earned by relatively disorganized offenders who use the cash to directly purchase legal goods without making use of any financial institution. Small-time thieves earning $30,000 annually are unlikely to make use of a bank or any other means of storing or transferring value beyond domestic hiding places. Although research carried out for one UK report [28] suggests that high turnover ‘drug mules’ can earn quite high incomes, it is impossible properly to estimate what share of these revenues will require laundering.Footnote 16

Though FATF pressures have generated significantly greater conformity in definitions of money laundering, Austria and Germany are among the few that still do not incriminate laundering of the proceeds of one’s own crime, whereas England and Wales applies the term laundering to all property of which one has knowledge or suspicion that it is criminal proceeds. In the U.S., 18 U.S.C. 1957, prohibits depositing or spending more than $10,000 of the proceeds from a Section 1956 predicate offense.Footnote 17 The broader definition may be useful for easy incrimination purposes but conveys a misleading sense of the scope of the problem. In principle, for any given country, one might want to sum the funds saved from all crimes and disguised in some form, and add to this the funds laundered in that jurisdiction from crimes elsewhere. The latter would vary with the attractiveness of the jurisdiction as an intermediate or final destination (and when summing countries’ laundering levels, one might need to be careful about double-counting).

Thus, if the right measure of AML success is a reduction in the volume of money laundering, there is little prospect of developing meaningful indicators at the national or global level. The conceptual problems are difficult and the measurement problems impossible. Fortunately, it turns out that ML is not truly the target of AML. Rather AML is aimed at a changing array of harmful activities that generate the laundered money. This is indicated by the fact that the mandate of FATF was originally restricted to drug moneys and has broadened by the expansion of the list of predicate crimes and the addition first of terrorist finance and then the violation of international sanctions. It is also aimed at more inchoate concepts such as financial integrity that, though socially important, are hard to identify clearly.

Data in the 3rd round MERs

This section draws on Halliday et al. [29]. We focused particular attention to three national MERs (Germany, Netherlands and Mauritius) for which we were able, with IMF assistance, to obtain interviews with national officials.

Between 2004 and 2012, every member of FATF and of the FSRBs was subject to an evaluation, referred to as a Mutual Evaluation Review (MER). The “Mutual” was intended to emphasize that this was a peer review, though back-scratching was limited by having non-peer experts from FATF, IMF and World Bank as well as independent professionals in the assessment teams.Footnote 19 The term evaluation was used loosely; these were assessments of compliance in terms of laws and institutions. The Fourth Round, discussed in the next section, is the first effort to assess effectiveness in the true sense of how the problem is affected by the program.

Why then discuss the 3rd round at all? The fourth round, started in 2014, will take 8 years to complete; the last evaluations will be done in 2022. Important countries such as Argentina and India will not have their next MER till 2021.Footnote 20 For the next few years, the 3rd round evaluations – and any follow-up reports of progress in addressing defects that may be required by the FATF or FSRB plenaries - will be all that are available for half the countries of the world. Thus the Basel Institute of Governance, in putting together its measure of national AML effectiveness, in 2016 relied on the 3rd round evaluations for all but 13 of the 149 countries that it includes in its Public Edition; the MERs constitute the single most important of the 14 components of the Index, accounting for 30% of the total weight. Thus the data used for the 3rd round are an important element of what is known about AML efforts now; they are not merely history. Preparation for a MER is an important public policy activity, and a failure to think through the sort of critique that might be offered can lead to unpleasant consequences for the country that can persist over time.

Though countries care about their reputations, the very leisurely pace of the MERs raises questions about their real importance. Brazil is a country with serious problems of corruption and associated money laundering that have recently led via Operation Lava Jato (Car Wash) to the indictment of major businesspeople and politicians including its last three Presidents. It was last evaluated in 2009–10 – before these investigations and prosecutions began, but long after the alleged corruption began - and will not have its next evaluation till 2021. Money laundering is, by all official accounts, a fast-moving target much affected by the many changes in the financial systems of the world. An 11-year old MER – updated mainly in respect of criticisms of inadequate procedures against terrorism finance - is likely to be badly dated, yet that is all that will be available officially for Brazil in 2020. It is fair to note that a MER is an expensive exercise (perhaps as much as $1 million if all costs are considered) and demanding in terms of the time of senior officials as the country seeks to impress the evaluators: but if costs as slight as these are sufficient to justify an 11 year gap, one must question just how important are timely AML assessments.Footnote 21

We consider the data used first to describe the problem and then the primary response indicator (SARs) in the 3rd round MERs.

General situation Footnote 22

Each assessment report under the 2003 Standard includes a section entitled “General Situation of Money Laundering and Financing of Terrorism” (Section 1.2). It is meant to provide a set of statistics and brief narrative comments about crime, criminal justice, and the risks faced by the nation with respect to specific crimes. It describes the problem with which AML/CTF efforts must deal and/or the success of AML/CTF efforts to date. This is potentially a critical prelude to the assessment itself. In its MERs on the Netherlands and Germany, the IMF sought to go significantly further than did most reports from any assessor body in the 3rd round. The difficulties it confronted illustrate the challenges posed by analysis of the “General Situation”.

The ‘General Situation’ section previously played a very limited role in the assessment of a nation’s AML/CTF system. The section was typically very brief. For example, for Mauritius it occupied less than one full page. For Armenia it occupied three pages, but two of those were devoted to a table of statistical data on predicate offences. The innovative effort by Fund assessors to provide a more comprehensive analysis for Section 1.2 in the MER for Netherlands, where many more data are available, led to longer sections of nine pages for the Netherlands, and eleven pages for Germany. The section on terrorist financing is extremely short; for the Netherlands barely one page (paragraphs 80–83) and for Germany two pages (paras 70–79). That may be seen to reflect the scarcity of materials available to the assessors, given the high level of security classification surrounding so much terrorist-related information.

The choice of indicators to describe the nation’s crime problem reveals difficulties. The indicators should relate to the programmatic intervention i.e. the crimes included should be ones for which AML is plausibly a method of control. Which fall in that category? In many countries homicide rates are included, even though there is only the most strained connection between AML and general levels of homicide. Domestic disputes account for most homicides in many countries. In some countries, homicides come from conflicts over resources, licit and illicit, and the latter include a variety of market-related offenses from drugs and people trafficking to illegal logging and land seizures. Stripping out organized crime-related homicides from general homicide data is desirable but quite difficult and has been infrequently attempted.Footnote 23 It would, for example, be difficult to suggest that the persistently high homicide rate in the United States (relative to other OECD nations) was indicative of a problem for which better AML was an important part of the solution; nor would AML be expected to impact (or to have impacted in the past) on the low homicide rate in the UK. A better argument could be made for the relevance of AML to homicide rates for some Central American and other countries, because there is credible evidence that most of those homicides are related to organized crime and illegal markets. None of these considerations are reflected in the MERs.

The cross-national comparisons are also hardly relevant. To state that Germany has a crime rate a little higher than the mean of a United Nations global survey of countries of all levels of development is to provide no relevant assessment as to whether the country is doing well or badly with respect to crime control.Footnote 24 If comparisons of crime rates matter, then there are other sources of data and analysis that would allow better understanding of a country’s problem; for example comparisons could be made to countries with a similar cluster of attributes or configurations, for example, with similar per capita GDP, unemployment rate, and other indicators relevant to their crime and their laundering rates. At a minimum, data from the European Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics [32, 33] would have served as a better source for comparison than would global averages.

The analysis of crime statistics sometimes betrays a poor understanding of the sources of the data. For example, drug offenses per 100,000 population is presented along with property crimes per 100,000, though these are not truly comparable. Property crimes represents the number reported to the police, often motivated by the contractual requirement for an ensuing insurance claim. However, drug offenses are simply drug arrests, since there is no separate reporting of drug transactions. The Netherlands has a low rate of recorded drug offenses because it does not arrest individuals in possession of small amounts of marijuana, which account for the bulk of all drug arrests in most Western countries.Footnote 25 As measures of the incidence and prevalence of different forms of drug use, much better data are available for the EU countries from the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction.Footnote 26 Drugs trafficking, much closer to a useful measure, is a far more challenging phenomenon to measure, but at least for the Netherlands, the Dutch Ministry of Justice’s own Organised Crime Monitor gives a good time series perspective on criminal careers and involvement in a range of serious crimes, more recently including fraud and cybercrimes.Footnote 27

The statistical measures that are presented differ across countries. For example, in Germany there were data on the Adult prosecution rate (per 1000 population); Clearance rate (closed cases/reported crimes); Embezzlement rate; Fraud rate; Number of drug-related, economic and money laundering offenses, 2003–2007. Though most of the above are readily available for the Netherlands, the Dutch MER included none of them but did include numbers of robberies, burglaries, and drug trafficking offenses. No explanation was offered for the choice of these different indicators in different countries. Official statistics and one other source of data in some developed countries - crime victimization data – give little guide to the financial components of household or organized crime, especially not illicit service crimes or fraud and cybercrimes: but the most economically costly crimes may not always be the most harmful crimes or the best targets for AML efforts.Footnote 28

The explanation for variation globally across MERs is almost certainly lack of available data and a lack of time for assessors to find alternative types of data. Despite quite modest requests, Eurostat [36] was unable to get a complete set of criminal justice data for EU Member States. The MER assessment team normally relies on what is published in the country and on what officials present to it. So, the Netherlands MER devotes a whole paragraph to the issue of marijuana cultivation, including a graph on “Number of dismantled [cannabis] nurseries between 1991 and 2006”. Yet the revenue generated by cannabis cultivation is estimated to be between €182 million and €424 million per annum, only about one quarter of the total for drugs which itself is only one tenth of the estimated total proceeds of crime. That would be fine if the sections on other generators of proceeds were longer, but in fact they are not.

It appears that no systematic filter was used to identify what data were relevant to describing the general situation of money laundering and terrorism financing. Instead the evaluation teams opportunistically used whatever broadly relevant data was available, resulting in considerable inconsistency across countries. This may have been the only realistic solution in context, but it points up the lack of importance of data on national crime problems and ‘imported’ laundering to the assessment of the AML process at that time.

Proceeds of crime

As already noted, the Proceeds of Crime (POC) is a plausible starting point for assessing the money laundering problem in a country, even if it is not itself an estimate of the volume of domestic and/or foreign money laundered. Many MERs attempt to provide an estimate of POC, both in absolute terms and as a percentage of GDP. However, the state of the art is weak. Consider for example, efforts to estimate total revenues from drug sales in the United States, perhaps the instance of Proceeds of Crime that has been most studied. In 2001, the Office of National Drug Control Policy estimated that expenditures on marijuana were $10.5 billion in the year 2000.Footnote 29 Ten years later, the same research team, using essentially the same data and methods but with different assumptions about a number of parameters, estimated that expenditures for 2001 were $25 billion,Footnote 30 even though the underlying figures on use had not changed.

The Netherlands has been more active than almost any other nation in promoting research on money laundering and POC; this was also true at the time of its last MER. The Netherlands MER cites the results of a contested study published under Dutch Ministry of Finance auspices [37]. It notes correctly that the study has been strongly criticized by academics (e.g. [38]). Perhaps as a consequence, the assessor body chose to create its own estimate of the components of Proceeds of Crime, using a Dutch-language document cited in the Unger study as well as some updating of that study. There is no way for a reader to judge the validity of the assessor figures, which lack face validity.Footnote 31 None of the other published Dutch material on organized crime and money laundering was referenced by the team.

By what criteria should the assessors judge whether the POC is large or small? What share of GDP is small enough that a nation may be judged to have, by whatever means, achieved ‘adequate’ control of its money laundering and/or financial integrity problem. Does it matter whether the crimes are primarily domestic or committed elsewhere? Estimates of domestic POC are exceedingly difficult to establish and were not persuasive in the MERs we reviewed (see [40] for an ambitious set of recommendations for analysis of hard-to-reach data and data proxies). Furthermore, one of the key areas in allegations of money laundering laxity, in places such as Cyprus, Panama, Switzerland, the U.K. and ‘its’ overseas territories, and the U.S., is that ‘financial secrecy’ countries launder proceeds of crime from other countries. Such figures are essentially impossible to calculate, though good examples can be found to illustrate the risks (and perhaps that is enough for some purposes). Ultimately there was no basis for assessors to reach a judgment about whether Proceeds of Crime (domestic and international) were large enough to constitute a major ML problem for that country or for others. Indeed, it remained implicit that wherever the crimes occurred, the laundering thereof was ‘the problem’ of the country under evaluation.

Suspicious transaction reports Footnote 32

Recommendation 32 in the 2003 Standards required that countries should maintain comprehensive statistics on matters relevant to the effectiveness and efficiency of their AML/CFT systems.Footnote 33 Most countries are able to produce only the number, and not the total value of the suspect transactions, though the latter would be obtainable with some effort.Footnote 34 The problem with process statistics like these is that they are subject to multiple interpretations which can then become a continuing source of tension between country officials and the assessor panels. The focus here is on STRs as an example, but similar comments can be made about the prosecution and conviction figures.

The German MER included a table of STRs for five countries (three Continental, plus the U.K. and Canada) from 2006 to 2008 (p.170) and concluded that Germany’s rate was comparatively low, indeed more than an order of magnitude smaller than the British figs. (7000 vs. 210,000). It was also low with respect to a normalized reporting of STRs against population and GDP. While it is valuable and even necessary to undertake careful analysis of STRs as the assessors intend, the presentation of data here has problems which make inferences highly questionable. As the German MER noted, nations differ in their approach to reporting by financial institutions. Some use a low threshold; a report should be filed if there is any concern at all. Others favor a high threshold, putting on the reporting institution the burden of an initial assessment of the credibility of the claim, an especially important issue where the law freezes the reported suspicion for a short period given to prosecutors to decide whether or not to open a money laundering case.Footnote 35 The Mutual Evaluation Report on Germany noted the STRs were of high quality but was critical that the internal review by the financial institutions led to violations of the FATF requirement that STRs be filed “immediately” (p.174).

There is no known empirical basis in outputs or outcomes for choosing between these approaches, especially when there is no measurement of what effort (including speed) the public authorities put into analyzing or disseminating the reports if and when received, or with the results that effort brings. There is no comparative analysis to show that STRs in countries that apply more stringent criteria (e.g., Germany, Netherlands or Switzerland) are comparable to STRs in low threshold countries (e.g., U.K. or U.S.A.). Country officials asserted they were not comparable and further stated, rightly or wrongly, that the IMF assessors failed to grapple adequately with this lack of comparability. The 3rd round MERs elevated the average, or perhaps even the high-end numbers, to the status of “best practice”.Footnote 36 We note that Germany STR numbers rose rapidly after the 2010 MER; from 7349 in 2008 to 24,054 in 2014 ([45], p. 8); we have no systematic information as to the source of such a large and rapid increase but it is reasonable to suggest that it was a response to the FATF criticism.Footnote 37

Prosecutions for money laundering are the consequence of investigative follow up and prosecution attitude, competence and resources, not just of the number of STRs. The lack of qualitative insight into the nature and seriousness of prosecutions is also a major issue. To avoid criticisms for low prosecution rates, some countries might choose to prosecute more self-laundering cases, whereas for a strategic impact on laundering behavior, it might be preferable to prioritize a smaller number of prosecutions or other interventions against key enablers. Though there is no evidence of such strategic behavior having occurred in the 3rd round evaluations, the Reports certainly make that a possibility; see Deleanu [46] for a study suggesting strategic manipulation.

Fourth round evaluations

By the end of the 3rd round there was general agreement on the necessity for developing more meaningful methods of evaluation, to go beyond the focus on formal compliance. FATF set up many working groups that produced a variety of documents providing guidance for the fourth round of evaluations. The key document is entitled Methodology for Assessing Technical Compliance with FATF Recommendations and Effectiveness of AML/CFT Systems published in 2013. On effectiveness, the Methodology documents say “It seeks to assess the adequacy of the implementation of the FATF Recommendations, and identifies the extent to which a country achieves a defined set of outcomes that are central to a robust AML/CFT system. The focus of the effectiveness assessment is therefore on the extent to which the legal and institutional framework is producing the expected results” (p.4). For the first time, the Methodology articulates goals and objectives. We do not analyze these here (see http://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/4th-Round-Ratings.pdf for results to date) but focus instead on the data requirements.

National risk assessments

A required component of the 4th round Mutual Evaluations is the preparation by each country of a National Risk Assessment (NRA), to be conducted before the FATF/FSRB evaluation team arrives to collect data in-country; such an assessment does not have to be published. This has become a major activity, highlighted in the MERs themselves and assessed critically in the first of the Technical Appendices at the back of each Report. Assessments can be tough; for example, Norway was criticized for its inadequate NRA in its 2014 MER.Footnote 38 The NRA, which brings together many agencies involved in AML activities,Footnote 39 provides a platform for understanding the relationship of the FATF regime to data collection and analysis.

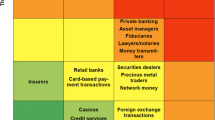

The 2013 guidelines for the NRA are extensive; the official FATF document is 60 pages.Footnote 40 Yet they are not detailed or formulaic: “This guidance document is not a standard…The practices described in this guidance are intended to serve as examples that may facilitate implementation of these obligations in a manner compatible with the FATF standards” ([47], p.5). The guidelines help member states to implement Recommendation 1 that they “identify, assess and understand” the ML/TF risks they face. Risk is seen as the intersection of threats, vulnerabilities and consequences. A particular sector (banks, casinos, accountants) might be seen as high risk if it faced serious threats (many efforts to launder money), had weak controls and/or the consequences of a money laundering violation in that sector had particularly serious consequences. The NRA is presumed to require collaboration among many different government agencies and also various private sector stakeholders.

The guidelines are refreshingly candid about the limits of quantitative data in this field.

“While quantitative assessments (i.e. based mostly on statistics) may seem much more reliable and able to be (sic) replicated over time, the lack of available quantitative data in the ML/TF field makes it difficult to rely exclusively on such information. Moreover information on all relevant factors may not be expressed or explained in numerical or quantitative form and there is a danger that risk assessment relying heavily on available quantitative information may be biased towards risks that are easier to measure and discount than those for which quantitative information is not readily available.” (p.17)

This skeptical view about quantitative data is consistent with a contemporary critique in social sciences that the emphasis on quantification trades precision for validity [48,49,50].

We examined five published NRAs to assess the kinds of data and analysis that were used to implement the risk assessments.Footnote 41 The five we chose are from countries with well-established reputations for professional competence in financial regulation; Canada, Japan, Singapore, the United Kingdom and the United States. Thus, we assume that they are likely to be well above average in their presentation and analysis of data. Unfortunately, neither the Dutch nor the German NRAs are completed and published at the time of writing.

What is striking is how little data or analysis of data played in most of the NRAs we reviewed. Singapore and the US simply used this document as an opportunity to describe the ways in which money is laundered; each type of money laundering was illustrated with a summary of a specific case. The Reports provided minimal quantitative data; estimated proceeds of crime in the US Report and the number of cases for three kinds of offenses in the Singapore Report. There was no indication in the brief methodology sections of the two Reports that an effort had been made to systematically survey experts about their assessments of threats/vulnerabilities/consequences or risks. The Reports included summary judgments of a comforting and rather empty kind: for example, the US Report states “AML regulation, supervision, enforcement, and compliance in the United States are generally successful in minimizing money laundering risks". No basis is provided for justifying that claim to the skeptical reader, who may perhaps be disturbed by the flow of large judgments and regulatory penalties in the U.S. against the most prominent banks caught in large scale and systematic violation of AML/CFT regulations.Footnote 42 Another major deficiency about the U.S. report is its narrow focus on domestic context and silence about possible risks associated with external criminal flows, beyond brief reference in the introductory parts. Given the role of the U.S. in international trade and its use of dollar clearing as the basis for its Federal and New York City & State global financial crime policing and prosecution role, this seems extraordinary unless it is implicitly deemed that foreign crimes and terrorism do not constitute a risk (or threat) to the U.S..

The Japanese Report contained numerous Tables and Figures with detailed data on enforcement actions; illustrative are Tables with data on the number of restraining orders issued and amounts confiscated before prosecution under drug laws and on the number of STR-initiated cases by crime type. However these numbers were taken at face value as indicative of the underlying distribution of money laundering types, a naïve interpretation. No effort was made to collect or present any other kind of data. There was no summary assessment of the risks of particular products, sectors or services, merely descriptions of what was currently being done to mitigate risks.Footnote 43

The British NRA (which was revised in 2017, though the later report contained less information about methodology) took the exercise seriously, both in terms of attempting to measure the relative risks of particular sectors through multiple sources and also identifying weaknesses in knowledge. It acquired data from experts and subjected them to peer review (p.10). It provided detailed quantitative estimates, showing the components of the final risk assessments. The Canadian NRA also methodically collected and analyzed expert judgment to provide consistent relative risk assessments across sectors.

Table 1 provides a summary of the data used in the five Reports.

The NRA, admittedly in its initial implementation, suggests how weakly FATF has articulated the role of data and data analysis in the assessment process and/or how modest have been the attempts to implement that requirement.Footnote 44 The Japanese, Singaporean and American NRAs did not include any summary figures on the risk of specific classes of products or transactions, while the Canadian and British NRAs provide detailed risk assessments, reflecting both qualitative and quantitative data, though there remain gaps in their coverage. Our point here is that if data are to be used at all, more effort needs to be made to ensure that they are reasonably relevant and valid.

By mid-2017, neither Japan nor the UK has had its 4thround Mutual Evaluation, scheduled for 2019 and 2018 respectively. The Singapore NRA received a positive evaluation in the MER, with a comment that there were modest deficiencies. The focus of the comments was on the soundness of the process, rather than on the adequacy of the methodology. The Canadian Report was positively assessed in the MER: the estimates of POC were repeated without comment, and the Report (para 15) complimented Canada on its judgements of the magnitude of different threats, its distinguishing of foreign from domestic ML threats. The MER also was complimentary that the NRA broke these down by types of crime, asserting that tax evasion and corruption ML were bigger threats than assessed, and that asset recovery is low. Otherwise, most of the data discussed were process data of a kind little different from the third round. The U.S. MER made little comment on the data, citing the UNODC estimates without criticism and not using other cost of crime data that were available. In all three cases, there was more material on crime context than in previous evaluations, but the substantial data were about money flows, FIU caseloads, criminal justice and asset recovery, which were not substantially related to the extent of money laundering.

Concluding comments: Evaluation in a data-poor environment

The AML/CTF system has not been the subject of many challenges in the post-9/11 era, in contrast to the struggles that had preceded 9/11 when it had come to be seen as primarily a crime-fighting tool of modest actual impact. Fighting terrorism finance is a goal about which there is little controversy among the major powers, and any countries with reservations about this objective generally remain silent. Whether the FATF regime has accomplished much in the fight against terrorism beyond enabling easier tracing of networks of donors and supporters and freezing of modest amounts of assets of banned organizations is disputable [51, 52]. However, the political risk of being labeled as supporters of terrorism is great enough that criticism of the CTF regime has been confined to the margins [53], most recently focused on counter-productive consequences of the threat to the flow of remittances to developing countries with terrorism risks [4]. The sanctions regime – an important tool of financial foreign policy - is discussed elsewhere in this volume.

We are by no means the first scholars to comment on the failure of the AML system to produce credible evidence of the effectiveness of the system. Jason Sharman [2] noted that the failure to provide any positive evidence of effectiveness has proven no barrier to the rapid dissemination of the FATF regime to all parts of the globe. His inquiry focused on how the system has diffused in the absence of evidence that it worked. This paper can be viewed as an effort to describe how the system has managed to issue regular reports that include the word “evaluation”, an important label in contemporary policy circles, without in fact contributing much to knowledge of whether the FATF regime is indeed contributing significantly to global or even national wellbeing.

Official documents represent an analytic challenge in understanding the system because they include statements that have rhetorical rather than substantive goals. Thus the FATF Global Threat Assessment states "Because a chain is only as strong as its weakest link, the international community must rely on all countries to establish effective AML/CFT regimes..." Yet it is clear that there are many countries that have very weak AML/CFT systems but represent a minimal threat to the global system. The very weakness of the legal system that helps lead Uganda to the 4th lowest position of the Basel Institute’s ML rankings also makes that country an unattractive country in which to place financial assets, stolen or otherwise, for the medium or long term, especially not for funds from crimes elsewhere. Thus the statement is not to be taken at face value but rather as an exhortation to governments to take AML seriously and to do their bit for the global community. This is perhaps an appropriate goal for a global standard-setting body to set for one of its flagship documents. But once that is conceded, the analyst is left wondering which statements are to be taken at face value.

Nonetheless, analysis of MERs and supporting documents such as the National Risk Assessments shows that the efforts at ‘real’ evaluation have been very limited. One indication of how low a priority is given to evaluation is the leisurely schedule of the Mutual Evaluation Reports (roughly once every 8 years).Footnote 45 No one believes that ML is a static phenomenon and the economic and opportunity costs of doing these full scale evaluations are surely modest set against claims of billions of dollars in money laundering and perhaps in the associated harms. Though it is always arguable that scarce operational staff time is displaced to accountability exercises, a global system that thought AML important would find ways of producing more frequent evaluations. It might also revisit the sort of expertise that is brought to these evaluations and whether the benefits from the additional cost of expert assessment systems are outweighed by the possibly greater legitimacy of peer assessments (though detailed consideration of such issues lies outside this paper).

However, data and existing crime data collection efforts exemplify the superficiality of the claims that these are truly evaluations. The Methodology document for the fourth round evaluations makes sensible recommendations about both the nature of the data to be used for evaluation and ways in which they might be analyzed. However, the evidence from early 4th Round MERs suggests that despite efforts to generate much better FIU and other process data, neither quantitative nor qualitative data on serious criminality have yet found a well-defined place in the evaluation process. International efforts to encourage or compel private financial data flows into ‘government[s]’ for risk analysis and to promote faster exchanges of information for asset freezing/confiscation and successful prosecution of serious criminals are a solid enough intermediate objective, unless used oppressively against political or personal opponents by elected despots or by ‘dictators without borders’ [54],. Efforts to collect better data to measure and test claims about those improvements and their impact on the ways offenders and offending are dealt with are worthwhile, especially if they distinguish between major and minor offenders and between self-launderers and professional ‘enablers’. Data will always require interpretation: Gold and Levi [43] found that many STRs followed arrests rather than led to them, so simple correlation is not enough. U.K.-led efforts to share and fuse suspected transaction data between a select number of banks and between them and enforcement agencies via the Joint Money Laundering Intelligence Taskforce (JMLIT)Footnote 46 - a trend that has begun to spread elsewhere, e.g. Hong Kong and Singapore - reflect enormous frustration that the (inadequately measured) huge and growing cost of compliance has so little observable effect and seems highly cost-inefficient.

However, such regulatory, criminal procedure and criminal justice enhancements are not the same as serious and ‘organized’ crime reduction. For the latter, we need a broader set of tools, including a much more serious focus on measuring domestic and foreign crime proceeds and the harms that the offenses and their laundering cause: the latter may come from both the criminal acts themselves and the ‘threat actors’ who carry them out. We may expect different targets to have different susceptibilities to partial or complete deterrence by financial interventions. The extent to which Grand Corruption will truly be reduced by anti-PEP measures and ex post facto asset confiscation is an open question [55]; likewise, after confiscation, some organized criminals may work harder at crime to get back to their earlier wealth or lifestyle expenditures. We are not suggesting that the conceptualization and generation of relevant data is at all an easy task but in its absence, claims that countries have less or more effective systems will be open to allegations that judgments about the effectiveness of their AML regimes are merely ad hoc, or impressionistic, or even politicized. Such allegations reduce the legitimacy of the evaluations and the institutions being evaluated. Despite our anticipation that greater criminological expertise will be displayed by country assessors over time, the design and operation of the AML/CTF system will continue to reflect faith and process rather than build upon reliable evidence of actual positive impacts on institutions and social wellbeing.

Notes

We are happy to acknowledge detailed and helpful comments from Steve Dawe, Kuntay Celik, Emile van der Does de Willebois, as well as two anonymous referees and Mark Nance. All remaining errors are the authors’ responsibility.

Horror stories of mistaken identity abound; for example, a Middle Eastern immigrant in the Netherlands was suddenly denied access to his bank account because his very common name was on one of the lists. In the aftermath of European court rulings that the rights of the defense were infringed, appeals procedures were instituted in the UNSEC designation process which permitted de-listing. Human rights advocates would argue that social harm arises where due process is not followed, irrespective of ‘actual’ ML/TF intent by the suspect.

See https://www.fincen.gov/news_room/; https://www.dea.gov/ops/money.shtml; https://www.justice.gov/criminal-afmls/afmls-press-releases; https://www.irs.gov/uac/examples-of-money-laundering-investigations-fiscal-year-2016; https://www.ice.gov/money-laundering; https://www.fbi.gov/news/pressrel. For example, there were 266 FBI press releases referring to money laundering 2014-mid-2016.

From then Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz’s statement to NATO Ministers Meeting, September 2001. See further A. Evans-Pritchard, ‘US asks Nato for help in “draining the swamp” of global terrorism’ (2001) The Daily Telegraph 27 September at <http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/main.jhtml?xml=/news/2001/09/27/wusa27.xml>.

See for example the Basel Index of AML activities and risks: “As there are no reliable quantitative data on money laundering..” [6]

The High-Level Objective is stated as “Financial systems and the broader economy are protected from the threats of money laundering and the financing of terrorism and proliferation, thereby strengthening financial sector integrity and contributing to safety and security.”

We recognize that this is a narrow view of the concept of financial integrity, but there is little clarity on how we can tell what integrity means or does not mean. In pre-AML days, bankers would have accepted proceeds of crime without being bribed, because they thought taking client deposits was their job!

See Alldridge [10] for a principled objection to the widening of the concept. For a critique of the breadth of a recent EU proposal on money laundering criminalization, see http://ccbe.eu/fileadmin/speciality_distribution/public/documents/CRIMINAL_LAW/CRM_Position_papers/EN_CRM_20170331_CCBE-Comments-on-Commission-Proposal-on-countering-money-laundering-by-criminal-law.pdf.

http://www.theguardian.com/global/2009/dec/13/drug-money-banks-saved-un-cfief-claims. If Costa said this, he confused drugs profits with drugs revenues, which the sum cited more accurately represents.

The World Bank is attempting to develop more sophisticated models for the estimation of money laundering at the national level. For an early effort with Colombia see Villa et al. [15].

Michel Camdessus, then the Managing Director of the IMF, did not claim that the IMF had produced the estimate but only that such estimates had been made by others: however this refinement has been lost in the subsequent narratives.

Oddly enough the 2015 US National Risk Assessment uses UNODC estimates of drug revenues in the US rather than those of [16], even though the latter were sponsored by the Office of National Drug Control Policy and first published in 2014.

For analogies elsewhere, see the valuable collection edited by Andreas and Greenhill [19], which deals only very lightly with laundering and fraud.

There is an intellectual, legal and moral position under which funds spent on crime commission and post-crime lifestyle still count as ‘criminal benefit’ for the purpose of UK Proceeds of Crime Confiscation Orders. This leads to the aggregation of large amounts of funds deemed unpaid, on which notional interest has to be paid, artificially creating an ever-higher unredeemable attrition rate (Home Affairs [24,25,26]).

It is important to focus on gross revenues because estimating net revenues requires information about what DTOs pay to produce or purchase the drugs, and data are far too poor to permit this.

One complexity points in the other direction, to underestimates of the demand for money laundering services in the drug trade. Each level of the trade has to deal with total revenues, not just value added, so there is a cascading effect; however that covers only the high levels of the trade and does not include retailing or low level wholesaling.

In addition to existing mental element requirements, a source of potential variation is the inclusion of currency export violations as a predicate crime in money laundering totals. We are grateful to Peter Alldridge for this point.

The extent to which this succeeded in preventing backscratching differed across FSRBs. MERs conducted by MENA FATF (covering the Middle East and North Africa) and CFATF (covering the Caribbean) were thought by many professionals to be less objective than others, but there were variations within the work of the FSRBs, whether judged ‘better’ or ‘worse’. [Do you mean that there was variation within FSRBs as well as between FSRBs? Clarify]

The timeline for evaluations can be found at http://www.fatf-gafi.org/calendar/assessmentcalendar/?hf=10&b=150&s=asc(document_lastmodifieddate)&table=1

In addition to open source and specially commissioned studies, there are other official sources of information about money laundering in Brazil (and other countries). For example the annual US Department of State Money Laundering assessment (INCSR), which focuses on drugs and related laundering activities in Brazil in judging it to be of primary concern for money laundering. The OECD transnational bribery evaluations also provide information. The Brazilian MER does not neglect the issue of corruption, but perhaps understandably did not focus in it in its criticisms, since most revelations came to light after its MER, as was also the case with scandals involving Cyprus and Panama.

The individual MERs are listed in a separate section of the References.

An intense and unsuccessful effort to determine what share of New York City’s homicides were related to the drug trade is Goldstein et al. [30]. Even after having access to individual case files, the analysts were unable to make decisions about one third of the homicides. Another effort was made by the UK [31], which found a small number and proportion of homicides were plausibly organized-crime related, perhaps – in our view – because guns are hard to get in the UK and because shootings receive a very high police priority there.

“Statistics issued by the United Nations indicate that Germany records more crimes than the average of the other surveyed countries. They also indicate that Germany has relatively higher incidence of drug-related crimes, burglaries, embezzlements, and frauds. Crimes against the person are proportionally less prevalent. On average, Germany proportionally prosecutes more frequently than other surveyed countries and has less people in prisons” (Germany MER para 55).

A footnote in the German Report makes this point at a very general level “Note: Crime statistics are often better indicators of prevalence of law enforcement and willingness to report crime, than actual prevalence of criminal activity.” (p.21) but it does not then apply this caution in the text.

The EMCDDA publishes a detailed annual report on the drug situation in each member state, plus Norway and Turkey. http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/edr/trends-developments/2016

See for example Kleemans et al. [34]

Office of National Drug Control Policy What America’s Users Spend on Illicit Drugs 1988–2000

Office of National Drug Control Policy What America’s Users Spend on Illicit Drugs 2000–2006

See the Netherlands MER ([39]: 24–25).

This includes Suspicious Activity Reports, a term that is often used interchangeably.

“This should include statistics on the STR received and disseminated; on money laundering and terrorist financing investigations, prosecutions and convictions; on property frozen, seized and confiscated; and on mutual legal assistance or other international requests for co-operation.” 2003 Standards, p. 11.

The statistics are for the number of STRs or SARs sent to the FIU. In many countries, it is unknown how many of these are disseminated or analyzed for investigative purposes. There will be some overlap in the SARs as each reporting institution reports on activities that may be carried out by the same individuals or networks using different institutions. However, except for those jurisdictions that collate all wire transfers or those – like Switzerland – that have relatively few but high value reports, it would be a laborious process to add up the dollar amounts of all reports. We note that the Netherlands ([41]: 4) now does so.

For an analysis of differences in reporting standards for filing an STR amongst European countries see Ferwerda [42].

Gold and Levi [43], confirmed later by KPMG [44], showed that even when the number of STRs was comparatively low in the U.K., most received very little investigative attention because of resource constraints. This is likely to be a universal finding unless STRs are quite few or entail automatic freezing, as in Liechtenstein and Switzerland. In the latter case, the consequences of reporting for the account-holder and for the reporting institution force the FIU and/or the investigating judge/prosecutor to investigate them seriously and relatively rapidly.

One experienced assessor noted that the SARs analyses are not central to the actual ratings. However as exemplified by the German MER, they can play a substantial role in the Report itself. Bankers interviewed subsequently commented that the German FIU later complained to them about the deterioration in the average quality and utility of their SARs, which illustrates the counter-productive risks from a focus on numbers.

“[T]he NRA has many weaknesses which make it of limited value to assess ML/TF threats.” (Norway MER, p.34)

For example, the Singapore NRA listed 15 agencies involved in its preparation (p.3).

http://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/content/images/National_ML_TF_Risk_Assessment.pdf. These were updated in 2015.

In some cases, there are other unpublished versions with classified or confidential information in them. Given that the FATF evaluation team does not have clearances, this version is irrelevant for the purpose of the MERs. Moreover, in some countries the more detailed version will be in the national language and thus not comprehensible to the evaluation team.

For a review of the many cases involving large fines against banks operating in the US, such as HSBC and Wachovia, see XX

For example, for trade in precious metals the final assessment paragraph read: “To mitigate the risk that precious metals and stones are misused for ML/TF, the Act on Prevention of Transfer of Criminal Proceeds requires dealers to conduct CDD including verification at the time of transaction and to make STRs. The industry makes voluntary efforts.” (p.65)

One official challenged this conclusion, arguing that tighter guidelines could not be specified at the global level, given differences among countries in capacity. This is an important point – better no data than invented data – but it does show the limitations of reliance on quantitative evidence.

For some countries, partial updates are required on specific issues identified in the MER.

References

Middleton, D., & Levi, M. (2015). Let sleeping lawyers lie: Organized crime, lawyers and the regulation of legal services. British Journal of Criminology, 55(4), 647–668.

Sharman, J. C. (2011). The money laundry: Regulating criminal finance in the global economy. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Artingstall, D., Dove, N., Howell, J., & Levi, M. (2016). Drivers & impacts of derisking. London: Financial Conduct Authority https://www.fca.org.uk/your-fca/documents/research/drivers-impacts-of-derisking.

CGD. (2015). Unintended consequences of anti-money laundering policies for poor countries. http://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/CGD-WG-Report-Unintended-Consequences-AML-Policies-2015.pdf.

Obermaier, F., & Obermayer, B. (2017). The Panama papers (Rev ed.). London: Oneworld Publications.

Basel Institute of Governance. (2016). Basel AML index 2016 report.

Levi, M. (2015). The impacts of organised crime in the EU: Some preliminary thoughts on measurement difficulties. Contemporary Social Science, 11(4), 392–402.

Levi, M. (2017). Assessing the trends, scale and nature of economic cybercrimes. Crime, Law and Social Change, 67(1), 3–20.

Tusikov, N. (2012). Measuring organised crime-related harms: Exploring five policing methods. Crime, Law and Social Change, 57(1), 99–115.

Alldridge, P. W. (2016). What went wrong with money laundering law? London: Palgrave.

Reuter, P., & Truman, E. (2005). Chasing dirty money. Washington: Institute for International Economics.

Walker, J., & Unger, B. (2013). Measuring global money laundering: The ‘Walker gravity model. In B. Unger & D. van der Linde (Eds.), Research handbook on money laundering (pp. 159–171). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Unger, B., Ferwerda, J., van den Broek, M., & Deleanu, I. (2014). The economic and legal effectiveness of the European Union’s anti-money laundering policy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

UNODC. (2011). Estimating illicit financial flows resulting from drug trafficking and other transnational organized crime. Vienna: United Nations.

Villa, E., Loayza, N., & Misas, M.A. (2016). Illicit activity and money laundering from an economic growth perspective: a model and an application to Colombia (policy research working paper 7578). World Bank. Retrieved from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/696421467996735910/pdf/WPS7578.pdf

Caulkins, J. P., Kilmer, B., Reuter, P. H., & Midgette, G. (2015). Cocaine's fall and marijuana's rise: Questions and insights based on new estimates of consumption and expenditures in US drug markets. Addiction, 110(5), 728–736.

Nitsch, V. (2015). Trillion dollar estimate: illicit financial flows from developing countries (Darmstadt discussion papers in economics, 227). Darmstadt: Darmstadt Technical University.

Reuter, P. (2012a). Dirty laundry. Foreign Policy, http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2012/04/19/dirty_laundry.

Andreas, P., & Greenhill, K. (2012). Sex, drugs and body counts. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Reuter, P. (Ed.). (2012b). Draining development? Controlling illicit flows from developing countries. Washington: World Bank Press.

Levi, M., & Reuter, P. (2006). Money laundering. In M. Tonry (Ed.), Crime and justice: A review of research (Vol. 34, pp. 289–375). Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Home Office. (2016). Action plan for anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist finance. London: Home Office.

NCA. (2015). National strategic assessment of serious and organised crime 2015. London: National Crime Agency.

Committee, H. A. (2016). Proceeds of crime (fifth report of session 2016–17). London: House of Commons.

PAC. (2016). Confiscation orders: progress review (seventh report of session 2016–17). London: House of Commons.

Wood, H. (2016). Enforcing criminal confiscation orders: From policy to practice. London: Royal United Services Institute.

Kilmer, B., Caulkins, J., Bond, B., & Reuter, P. (2010). Reducing drug trafficking revenues and violence in Mexico: Would legalizing marijuana in California help? Santa Monica: Rand.

Matrix Knowledge Group. (2007). The illicit drug trade in the United Kingdom (Online Report 20/07).

Halliday, T., Levi, M., & Reuter, P. (2014). Global surveillance of dirty money: Assessing assessments of regimes to control money-laundering and combat the financing of terrorism. Chicago: American Bar Foundation http://www.lexglobal.org/files/Report_Global%20Surveillance%20of%20Dirty%20Money%201.30.2014.pdf.

Goldstein, P., Brownstein, H. H., Ryan, P. J., & Bellucci, P. A. (1989). Crack and homicide in new York City, 1988: A conceptually based event analysis. Contemporary Drug Problems, 16, 651–687.

Hopkins, M., Tilley, N., & Gibson, K. (2013). Homicide and organized crime in England. Homicide studies, 17(3), 291–313.

Aebi, M. F., Aubusson de Cavarlay, B., Barclay, G., Gruszczyńska, B., Harrendorf, S., Heiskanen, M., et al. (2010). European sourcebook of crime and criminal justice statistics-2010. The Hague: Boom Juridische Uitgevers.

Aebi, M. F., Akdeniz, G., Barclay, G., Campistol, C., Caneppele, S., Gruszczynska, B., et al. (2014). European sourcebook of crime and criminal justice statistics 2014. Helsinki: HEUNI, 2014, 413 http://hdl.handle.net/10807/61296.

Kleemans, E. R., Brienen, M. E. I., & Van De Bunt, H. G. (2002). Georganiseerde criminaliteit in Nederland: tweede rapportage op basis van de WODC-monitor (organized crime in the Netherlands: Second report based upon the WODC-monitor). Den Haag: WODC.

Hafner, M., Taylor, J., Disley, E., Thebes, S., Barberi, M., Stepanek, M., & Levi, M. (2016). The cost of non-Europe in the area of organised crime and corruption: Annex II - corruption (PE 579.319). European parliamentary research service. Retrieved from http://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document.html?reference=EPRS_STU(2016)579319

Eurostat. (2013). Money laundering in Europe. Luxembourg: Eurostat.

Unger, B., Siegel, M., Ferwerda, J., de Kruijf, W., Busuioic, M., Wokke, M., & Rawlings, G. (2006). The amounts and the effects of money laundering. The Hague: Ministry of Finance.

van Duyne, P. C., & Soudijn, M. R. J. (2009). Hot money, hot stones and hot air: Crime-money threat, real estate and real concern. Journal of Money Laundering Control, 12(2), 173–188.

Netherlands. (2011). http://www.fatf-gafi.org/publications/mutualevaluations/documents/mutualevaluationreportofthenetherlands.html

Dawe, S. (2013). Conducting national money laundering or financing terrorism risk assessment. In B. Unger & D. van der Linde (Eds.), Research handbook on money laundering (pp. 110–126). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

FIU. (2016). Financial intelligence unit - the Netherlands: Annual report 2015. Zoetermeer: FIU- the Netherlands.

Ferwerda, J. (2012). The multidisciplinary economics of money laundering. Diss: Utrecht University.

Gold, M., & Levi, M. (1994). Money-laundering in the UK: An appraisal of suspicion-based reporting. London: Police Foundation.

KPMG. (2003). Money laundering: Review of the reporting system. London: KPMG.

BkA. (2016). 2014 ANNUAL REPORT financial intelligence unit (FIU) GERMANY. Wiesbaden: BundesKriminalAmt https://www.bka.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/EN/Publications/AnnualReportsAndSituationAssessments/FIU/fiuJahresbericht2014Englisch.html?nn=39788.

Deleanu, I. S. (2017). Do countries consistently engage in misinforming the international community about their efforts to combat money laundering? Evidence using Benford’s law. PLoS One, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169632.

FATF. (2013b). FATF methodology for assessing technical compliance with the FATF recommendations and the effectiveness of AML/CFT systems. Paris: FATF/OECD.

Ferrell, J. (2015). Cultural criminology as method and theory. Qualitative Research in Criminology, 1, 293.

Sampson, R. J. (2010). Gold standard myths: Observations on the experimental turn in quantitative criminology. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 26(4), 489–500.

Wright, R., Jacques, S., & Stein, M. (2015). Where are we? Why are we here? Where are we going? How do we get there? The future of qualitative research in American criminology. In J. Miller & W. R. Palacios (Eds.), Qualitative research in criminology: Advances in criminological theory (Vol. 20, pp. 339–350). New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

Levi, M. (2010). Combating the financing of terrorism: A history and assessment of the control of ‘threat finance. British Journal of Criminology, 50(4), 650–669.

Zarate, J. (2013). Treasury’s war: The unleashing of a new era of financial warfare. London: Hachette UK.

Hayes, B. (2013). Counter-terrorism, ‘policy laundering’ and the FATF: Legalising surveillance, regulating civil society. Amsterdam: Transnational Institute.

Cooley, A., & Heathershaw, J. (2017). Dictators without borders: Power and money in Central Asia. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Sharman, J. C. (2017). The despot’s guide to wealth management: On the international campaign against grand corruption. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Further Reading

European Monitoring Center on Drugs and Drug Addition (EMCDDA). (2017). European drug report 2016: trends and developments. Lisbon: EMCDDA.

FATF. (2013a). International standards on combating money laundering and the financing of terrorism & proliferation: The FATF recommendations. Paris: FATF/OECD.

FATF. (2014). Anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing measures - Spain. FATF: Fourth Round Mutual Evaluation Report www.fatf-gafi.org/topics/mutualevaluations/documents/mer-spain-2014.html.

Kilmer, B., Caulkins, J. P., Midgette, G., & Reuter, P. (2015). Cocaine's fall and marijuana's rise: Questions and insights based on new estimates of consumption and expenditures in US drug markets. Addiction, 110(5), 728–736.

Nance, M.T. (2017). Re-thinking FATF: An experimentalist interpretation of the financial action task force. Crime, Law and Social Change. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-017-9748-5.

U.S. State Department. (2014). 2014 international narcotics control strategy report (Vol. 2). Washington: US State Department.

Mutual evaluation reports

Armenia. (2010). http://www.coe.int/t/dghl/monitoring/moneyval/Countries/Armenia_en.asp

Armenia. (2015). http://www.fatf-gafi.org/publications/mutualevaluations/documents/mer-armenia-2015.html

Brazil. (2010). http://www.fatf-gafi.org/publications/mutualevaluations/documents/mutualevaluationreportofbrazil.html

Canada. (2016). http://www.fatf-gafi.org/publications/mutualevaluations/documents/mer-canada-2016.html

Germany. (2010). http://www.fatf-gafi.org/publications/mutualevaluations/documents/mutualevaluationofgermany.html