Abstract

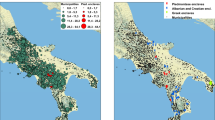

The article evaluates crime trends in south border American and Mexican sister cities using panel data analysis. The region offers a unique assessment opportunity since cities are characterized by shared cultural and historical legacies, institutional heterogeneity, and disparate crime outcomes. Higher homicide rates on the Mexican side seem to result from deficient law enforcement. Higher population densities in Mexican cities appear to also be a factor. Cultural differences, on the other hand, have been decreasing, and apparently do not play a substantial role. The homicide rate dynamics show opportunistic clustering of criminal activity in Mexican cities, while no clustering is found on the American side. Crime also appears to spill from Mexican cities into American cities. Homicide rates on both sides of the border have been falling faster than countrywide rates, leading, in the case of American cities, and against stereotypes, to rates below the countrywide rate in 2001.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Kearny and Knopp [9] summarized this point as follows: “while some may choose to begin the history of the border with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo at the end of the Mexican–American War, an argument can be made that the history of the border towns should properly commence with their founding. There are several reasons for taking this approach. First, the foundations of the societies and cultures of the towns that antedate the Mexican–American War lie in their pre-1848 history. Second, even before the creation of the U.S.–Mexican border in 1848, the towns along that later line were already border towns by virtue of lying on an exposed border of Mexico with wild Indian territory. Third, isolation by deserts from both Mexico to the south and from the United States to the north characterized these towns before as after the Mexican–American War.”

See for example “Key Crime & Justice Facts at a Glance,” Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/.

Mexico imposes strict controls on gun ownership due to a tradition of political centralization and to avoid insurrection, without much success however. Meanwhile, the American border states tolerate gun ownership due to philosophical, strategic and legal reasons, and because of political decentralization.

The Immigration Service was created in 1891 and the Border Patrol was established in 1924.

The data sources are the Grupo Interinstitucional para la Delimitación de Zonas Metropolitanas for Mexican cities, and the US Census Bureau for American cities.

In the years under the ICD-9 (WHO International Classification of Diseases) the homicide rate was created combining codes E960–E969 (homicide and injury purposely inflicted by other persons) and E980–E989 (injury undetermined whether accidentally or purposely inflicted), while in the years under the ICD-10 it was created combining codes X85-Y09 (assault), Y10-Y34 (event of undetermined intent), Y87.1 (sequelae of assault), Y87.2 (sequelae of events of undetermined intent), and Y89.9 (sequelae of unspecified external cause). The inclusion of undetermined cases, when applied to countrywide homicide rates, led to numbers that were approximately 10% higher than the equivalent rates calculated by the World Bank. City rates however became more in line with values reported by local newspapers, justifying the use of these code combinations.

Part of the data for Matamoros, Nuevo Laredo and Reynosa was collected from newspapers by the Centro de Estudios Fronterizos y de Promoción de los Derechos Humanos A. C. (Cefprodhac), a human rights non-governmental organization.

The AR(1) error component indicates, however, that occasional episodes of under or overreporting tend to have some time persistence.

UCR violent crime rates include cases of murder and nonnegligent manslaughter, forcible rape, robbery, and aggravated assault.

UCR property crime rates include cases of burglary, larceny-theft, and motor vehicle theft.

Notice that variable filns it is assumed exogenous because it presents a substantial amount of cross-border heterogeneity.

The effects of variables bptr it and Δinc it are not statistically different for cities on the two sides of the border, and therefore are estimated with a single coefficient as in models 1 and 2.

According to the 2004 UCR, the US had 2.3 law enforcement officers per 1,000 residents nationwide – 28% more than the border average of 1.8. Cities with population greater than 250,000 had 2.8 law enforcement officers per 1,000 residents nationwide, compared with 1.6 in San Diego and 1.9 in El Paso. Meanwhile, cities with population greater than 100,000 and lower than 250,000 had 1.9 law enforcement officers per 1,000 residents nationwide, compared with 1.4 in Brownsville, 2.0 in Laredo, and 2.2 in McAllen.

As discussed in “Empirical models,” the coefficients for groups of cities on the two sides of the border were not statistically significant.

References

Bailey, J., & Chabat, J. (2001). Public security and democratic governance: Challenges to Mexico and the United States. In The Mexico Project. Washington, DC: Georgetown University.

Bronars, S. G., & Lott, J. R. Jr. (1998). Criminal deterrence, geographic spillovers, and the right to carry concealed handguns. AEA Papers and Proceedings, 88(2), 475–479.

Comisión para Asuntos de la Frontera Norte. (2002). Seguridad Pública y Procuración de Justicia. In Programa de Desarrollo Regional Frontera Norte 2001–2006 (pp. 563–597). Tijuana: CAFN.

Coronado, R., & Orrenius, P. M. (2003). The impact of illegal immigration and enforcement on border crime rates. Research Department Working Paper 0303. Dallas: Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

Dell’Agnese, E. (2005). The US–Mexico border in American movies: A political geography perspective. Geopolitics, 10, 204–221.

Fajnzylber, P., Lederman, D., & Loayza, N. (2002). Inequality and violent crime. Journal of Law and Economics, 45(1), 1–40.

Gerber, J. (2003). Are incomes converging along the US–Mexico border? Mimeo, center for Latin American studies. San Diego: San Diego State University.

Gould, E. D., Weinberg, B. A., & Mustard, D. B. (2002). Crime rates and local labor market opportunities in the United States: 1979–1997. Review of Economics and Statistics, 84(1), 45–61.

Kearny, M., & Knopp, A. (1995). Border cuates: A history of US–Mexican twin cities. Austin: University of Texas.

Kelly, M. (2000). Inequality and crime. Review of Economics and Statistics, 82(4), 530–539.

Kugler, M., Verdier, T., & Zenou, Y. (2005). Organized crime, corruption and punishment. Journal of Public Economics, 89, 1639–1663.

Levitt, S. D. (1997). Using electoral cycles in police hiring to estimate the effect of police on crime. American Economic Review, 87(3), 270–290.

Levitt, S. D. (2004). Understanding why crime fell in the 1990s: Four factors that explain the decline and six that do not. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 18(1), 163–190.

Mains, S. P. (2004). Imagining the border and southern spaces: Cinematic explorations of race and gender. GeoJournal, 59, 253–264.

Neumayer, E. (2005). Inequality and violent crime: Evidence from data on robbery and violent theft. Journal of Peace Research, 42(1), 101–112.

Orrenius, P. M., & Coronado, R. (2003). Falling crime and rising border enforcement: Is there a connection? Southwest Economy, 3, 9–10.

Reames, B. (2003). Police forces in Mexico: A profile.(USMEX working paper series.) La Jolla: University of California, San Diego.

Willoughby, R. (2003). Crouching fox, hidden eagle: Drug trafficking and transnational security – A perspective from the Tijuana–San Diego border. Crime, Law and Social Change, 40, 113–142.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank A. Sachsida for insightful comments, J. Gerber and G. Hanson for kindly providing essential data, and the Texas Center for Border Economic and Enterprise Development at Texas A&M International University for financial support under the Texas Center Research Fellows Grant Program. Existing errors are nevertheless the sole responsibility of the author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Albuquerque, P.H. Shared legacies, disparate outcomes: why American south border cities turned the tables on crime and their Mexican sisters did not. Crime Law Soc Change 47, 69–88 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-007-9053-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-007-9053-9