Abstract

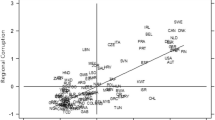

The problem of measuring changes in corruption internationally is significantly more daunting than that of estimating their levels. We compute trends in corruption for groups of geographically proximate countries, based on the geographic distribution of cases of cross-border bribes, and confirm that geographic variations in corruption are greater than time variations. They are then compared with changes in perceived corruption, as measured by Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index. We find that these alternative measures are not significantly correlated with each other. Using a panel data estimation technique, we attempt to explain trends in corruption. We only partially confirm results that are obtained when the purpose is to account for their levels in the context of a cross-sectional study. Overall, we conclude that the study of changes in levels of corruption is still in its infancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We are concerned with measurements of corruption at the international level. Over the last decades methods have been proposed to measure corruption that are based on “objective” data, as as an alternative to perceptions of corruption, or on victimization. With the exception of Escresa and Picci (2015), such attempts have however invariably been carried out for single countries, or for smaller geographic units. See for instance, Golden and Picci (2005), Glaeser and Saks (2006), Ferraz and Finan (2008), and Olken (2009).

Both are “meta-indexes” that are computed by aggregating ratings from several sources (Treisman 2007). Other perception-based measures are also available, some of them proprietary and consequently of rare use in academia, such as those included in the International Country Risk Guide (see http://www.prsgroup.com/). Victimization surveys also may allow for international comparisons; however, they tend to focus on petty (vs. grand) corruption, and sometimes use an oblique language in order to elicit honest answers, which leads to doubts as to whether what is reported has been experienced by the respondent, or is mostly informed by perceptions.

A recent update of the TI-CPI methodology should ensure that “a country’s Corruption Perception Index score will better capture changes in perception of corruption in the public sector of that country over time. However, due to the update in the methodology, 2011 CPI scores are not comparable with CPI 2012 scores” (Transparency International 2012).

According to searches using both the Internet search engines google.com and scholar.google.com, the number of hits of the TI-CPI is two orders of magnitude greater than that of the WB-CCI.

Trade flows are an imperfect proxy for the number of cross-border transactions which are vulnerable to corruption. For instance, there are likely differences in the propensities of corruption across sectors of the economy that in principle could be accounted for by developing a sectoral index. However, this would require an extensive effort at data collection (see Escresa and Picci 2015). Also, levels of corruption could influence trade patterns, but the available evidence shows that the impact would be contradictory, and likely modest (Dutt and Traca 2010).

Thus, it is the ratio of the actual number of cases involving z officials that were first enforced in the firm’s headquarter country and other third countries and the expected number of cases assuming that the cases are dispered based on trade shares.

The OECD convention entered into force on 15 February 1999. Most signatories approved the necessary implementing legislations by the end of 2000. See http://www.oecd.org/daf/anti-bribery/WGBRatificationStatus.pdf.

The sub-regions are Eastern, Middle, Northern, Southern and Western Africa; Caribbean, Central, Southern and Northern America; Central, Eastern, Southern, South-Eastern, and Western Asia; Eastern, Northern, Southern, Western Europe; Oceania. Appendix A provides a listing of countries belonging to each one of them.

We use an updated version of the database illustrated in Escresa and Picci (2015).

The measure of precision pertains to the probability of observing zero cases under the condition that the probability of corruption is the same for all countries. See Escresa and Picci (2015) for a detailed discussion.

We omit Oceania, where very low levels of corruption are registered, driven as it is by the virtuous cases of Australia and New Zealand.

Escresa and Picci (2015) discuss the assumptions underlying different interpretations of the PACI.

Note that higher values of the TI-CPI correspond to lower levels of perceived corruption, so that the negative sign of the correlation with the PACI is expected. Note also that the measure that we introduce in the next section to allow for comparability in time of the TI-CPI, which we call “median ranking”, takes higher values for higher levels of corruption—the same as the PACI. Similar considerations apply to the WB-CCI.

We choose 2003 instead of 2002—the middle year of the first of the five-year periods under consideration—because the country coverage increased significantly with respect to the previous year, from 102 to 133 (see Table 3).

As an exception, we consider the TI-CPI median ranking for 2003 instead of 2002 (the middle year of the first five-year period). See the previous note.

See Wooldridge (2010), pp. 76–82.

See Appendix B for details on the regressors.

The first difficulty is concerned with arriving at a conceptual definition of governance that can also be useful in finding its empirical counterpart (Rothstein and Teorell 2008). Others are skeptical about the use of the World Bank Governance Indicators for comparisons across time as the global averages are scaled to zero for each period as well as the likelihood that the changing scope of countries may affect the ranking (Arndt and Oman 2010, Knack 2006). Kaufmann et al. (2006, 2007) however contend that there is little evidence of remarkable trends in governance indicators and as such, will have inconsequential effects. Kaufmann and Kraay (2002) showed that while high income is associated with good governance, the evidence does not support that increases in the former lead to improvements in the quality of the latter.

References

Ades, A., & Di Tella, R. (1997). National champions and corruption: some unpleasant interventionist arithmetic. The Economic Journal, 107(443), 1023–1042.

Arndt, C., & Oman, C. (2010). Measuring governance. OECD Development Centre Policy Briefs, 39, 1.

Baltagi, B. (2013). Econometric analysis of panel data (5th ed.). New York: Wiley.

Brunetti, A., & Weder, B. (2003). A free press is bad news for corruption. Journal of Public Economics, 87(7), 1801–1824.

Cheung, Y. L., Rau, P. R., & Stouraitis, A. (2012). How much do firms pay as bribes and what benefits do they get? Evidence from corruption cases worldwide. National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 17981: 1–38.

Dutt, P., & Traca, D. (2010). Corruption and bilateral trade flows: extortion or evasion? The Review of Economics and Statistics, 92(4), 843–860.

Escresa, L., & Picci, L. (2015). A new cross-national measure of corruption. World Bank Economic Review. doi:10.1093/wber/lhv031.

Ferraz, C., & Finan, F. (2008). Exposing corrupt politicians: the effects of Brazil’s publicly released audits on electoral outcomes. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(2), 703–745.

Glaeser, E., & Saks, R. (2006). Corruption in America. Journal of Public Economics, 90(6), 1053–1072.

Golden, M., & Picci, L. (2005). Proposal for a new measure of corruption, and tests using Italian data. Economics and Politics, 17(1), 37–75.

Kaufmann, D., & Kraay, A. (2002). Growth without governance. The World Bank Policy Research Working Paper Series No. 2928:1–50.

Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Mastruzzi, M. (2006). Measuring governance using cross-country perceptions data. In S. Rose-Ackerman (Ed.), International handbook on the economics of corruption (pp. 52–104). Cheltenham: Elgar.

Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Mastruzzi, M. (2007). The worldwide governance indicators project: answering the critics. Policy Research Working Paper Series No 4149, The World Bank.

Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Mastruzzi, M. (2009). Governance matters VIII: aggregate and individual governance indicators, 1996–2008. Washington: World Bank, Policy Research Department. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 4978.

Knack, S. (2006). Measuring corruption in eastern Europe and central Asia: a critique of the cross-country indicators. World Bank Policy Research Department Working Paper 3968.

Lambsdorff, J. G. (2006). “Consequences and causes of corruption - What do we know from a cross-section of countries? In S. Rose-Ackerman (Ed.), International handbook on the economics of corruption (pp. 3–51). Cheltenam: Edward Elgar Publishing House.

OECD, Various years. “Country reports on the implementation of the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention.”http://www.oecd.org/daf/antibribery/countryreportsontheimplementationoftheoecdanti-briberyconvention.htm.

Olken, B. A. (2009). Corruption perceptions vs. corruption reality. Journal of Public Economics, 93(7), 950–964.

Rothstein, B., & Teorell, J. (2008). What is quality of government? A theory of impartial government institutions. Governance, 21(2), 165–190.

Saisana, M., & Saltelli, A. (2012). Corruption Perceptions Index 2012 Statistical Assessment. JRC Scientific and Policy Reports, European Commission.

Shearman & Sterling Llp. (2013). FCPA digest of cases and review releases relating to bribes to foreign officials under the foreign corrupt practices act of 1977. New York: Shearman and Sterling LLP. http://www.shearman.com/files/Publication/287c1af0-f9cb-4c11-805d-91c409975b41/Presentation/PublicationAttachment/83d9dc0b-b80c-4ca4-877b-9efbba0952e7/FCPA-Digest-Jan2013_010213.pdf. Accessed on 22 March 2016.

Teorell, J., Charron, N., Dahlberg, S., Holmberg, S., Rothstein, B., Sundin P., & Svensson, R. (2013). The quality of government dataset, version 15May13. University of Gothenburg: The Quality of Government Institute, http://www.qog.pol.gu.se.

Transparency International. (2009). OECD anti-bribery convention progress report 2009: enforcement of the OECD convention on combating bribery of foreign public officials in international business transactions. http://www.transparency-usa.org/news/documents/FinalOECDProgressReport2009.pdf.

Transparency International. (2012). Corruption perceptions index 2012: an updated methodology. http://cpi.transparency.org/cpi2012/in_detail/.

Transparency International. (2013). Exporting corruption: progress report 2013: assessing enforcement of the OECD convention on combating bribery. http://www.transparency.org/whatwedo/pub/exporting_corruption_progress_report_2013_assessing_enforcement_of_the_oecd.

Treisman, D. (2007). What have we learned about the causes of corruption from ten years of cross-national empirical research? Annual Review of Political Science, 10, 211–244.

United Nations. (2003). United Nations convention against corruption. https://www.unodc.org/documents/brussels/UN_Convention_Against_Corruption.pdf.

Van Rijckeghem, C., & Weder, B. (2001). Bureaucratic corruption and the rate of temptation: do wages in the civil service affect corruption, and by how much? Journal of Development Economics, 65(2), 307–331.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2010). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Mass: MIT Press.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank for useful comments Eric Chang, Elizabeth David-Barrett, two anonymous reviewers, and participants to the 2016 Midwest Political Science Association in Chicago. Lucio Picci acknowledges the financial support of the Fondazione Cassa dei Risparmi di Forlì and Laarni Escresa of the Philippine Center for Economic Development.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1. United Nations’ definitions of African geographical sub-regions

The United Nations’ definition of geographical sub-regions was adopted (Source: http://unstats.un.org/unsd/methods/m49/m49regin.htm) with the list shown below. Some territories, characterized by different juridical statuses, are omitted, and are indicated by an underline. The numbers next to each sub-region, indicate the number of countries which were considered in our analysis and, the figure in parentheses, the original number of territorial entities included in it. We consider Taiwan as an entity distinct from China.

Eastern Africa. 18 (20). Burundi, Comoros, Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya. Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritius, Mayotte, Mozambique, Réunion, Rwanda, Seychelles, Somalia, South Sudan, Uganda, United Republic of Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe.

Middle Africa. 9 (9). Angola, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Sao Tome and Principe.

Northern Africa. 6 (7). Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, Sudan, Tunisia, Western Sahara.

Southern Africa. 5 (5). Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia, South Africa, Swaziland.

Western Africa. 16 (17). Benin, Burkina Faso, Cabo Verde, Cote d’Ivoire, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Saint Helena, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Togo.

Caribbean 28 (28). Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, Aruba, Bahamas, Barbados, Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Cuba, Curaçao, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Grenada, Guadeloupe, Haiti, Jamaica, Martinique, Montserrat, Puerto Rico, Saint-Barthélemy, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Martin (French part), Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Sint Maarten (Dutch part), Trinidad and Tobago, Turks and Caicos Islands, United States Virgin Islands.

Central America 8 (8). Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama.

South America 14 (14). Argentina, Bolivia (Plurinational State of), Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Falkland Islands (Malvinas), French Guiana, Guyana, Paraguay, Peru, Suriname, Uruguay, Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of).

Northern America 5 (5). Bermuda, Canada, Greenland, Saint Pierre and Miquelon, United States of America.

Central Asia 5 (5). Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan.

Eastern Asia 8 (7). China, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of China, Macao Special Administrative Region of China, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Japan, Mongolia, Republic of Korea, Taiwan.

Southern Asia 9 (9). Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Iran (Islamic Republic of), Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka.

South–Eastern Asia 11 (11). Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Timor-Leste, Viet Nam.

Western Asia 18 (18). Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Cyprus, Georgia, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, State of Palestine, Syrian Arab Republic, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, Yemen.

Eastern Europe 10 (10). Belarus, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Republic of Moldova, Romania, Russian Federation, Slovakia, Ukraine.

Northern Europe 18 (18). Åland Islands, Channel Islands, Denmark, Estonia, Faeroe Islands, Finland, Guernsey, Iceland, Ireland, Isle of Man, Jersey, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway, Sark, Svalbard and Jan Mayen Islands, Sweden, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

Southern Europe 16 (16). Albania, Andorra, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Gibraltar, Greece, Holy See, Italy, Malta, Montenegro, Portugal, San Marino, Serbia, Slovenia, Spain, The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia.

Western Europe 9 (9). Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Monaco, Netherlands, Switzerland.

Oceania 25 (25). Australia, New Zealand, Norfolk Island, Fiji, New Caledonia, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Guam, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Micronesia (Federated States of), Nauru, Northern Mariana Islands, Palau, American Samoa, Cook Islands, French Polynesia, Niue, Pitcairn, Samoa, Tokelau, Tonga, Tuvalu, Wallis and Futuna Islands.

Appendix 2. Data Sources

Corruption cases. The main sources of data are Trace International Compendium’s, a database on international anti-bribery enforcement (http://www.traceinternational.org/compendium), US DOJ and SEC documents, and OECD reports (various years). Other databases and publications, such as Shearman and Sterling 2013; Transparency International 2009, 2013 and Cheung et al. 2012 were consulted. Various news sources, such as the Wall Street Journal Risk and Compliance Journal (http://www.wsj.com/news/risk-compliance-journal), and anti-corruption blogs like the FCPA Blog (http://www.fcpablog.com) were considered.

lGDP_pc: logarithm of GDP per capita. Source: IMF WEO, release of October 2015 (https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2015/02/weodata/index.aspx).

The secondary source of the next variables is the “Standard data” of the Quality of Government Institute dataset (Teorell et al. 2013) which in itself is an assemblage culled from various sources. The May 2014 release of the dataset was used. A brief description of each variable is provided, taken verbatim from the dataset’s codebook. The original source identified in the codebook is indicated.

rsf_pfi: Press Freedom Index (Source: Reporters Sans Frontières) “measures the amount of freedom journalists and the media have in each country and the efforts made by governments to see that press freedom is respected.” It ranges between 0 (total press freedom) and 100 (no press freedom).

wbgi_rle: Rule of Law (Source: World Bank) “includes several indicators which measure the extent to which agents have confidence in and abide by the rules of society. These include perceptions of the incidence of crime, the effectiveness and predictability of the judiciary, and the enforceability of contracts.” Higher scores correspond to better outcomes.

wbgi_rqe: Regulatory Quality (Source: World Bank) “includes measures of the incidence of market-unfriendly policies such as price controls or inadequate bank supervision, as well as perceptions of the burdens imposed by excessive regulation in areas such as foreign trade and business development.” Higher scores correspond to better outcomes.

wbgi_vae: Voice and Accountability (Source: World Bank) “includes a number of indicators measuring various aspects of the political process, civil liberties and political rights. These indicators measure the extent to which citizens of a country are able to participate in the selection of governments.” Higher scores correspond to better outcomes.

hf_efiscore: Economic Freedom Index (Source: Heritage Foundation) “uses 10 specific freedoms, some as composites of even further detailed and quantifiable components: Business freedom, Trade freedom, Fiscal freedom, Freedom from government, Monetary freedom, Investment freedom, Financial freedom, Property rights, Freedom from corruption, Labor freedom.” It ranges from 0 to 100, where 100 represents the maximum economic freedom. “Although changes in methodology have been undertaken throughout the measurement period, continuous backtracking has been used to maximize comparability over time.”

Appendix 3 — Tables

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Escresa, L., Picci, L. Trends in Corruptions Around the World. Eur J Crim Policy Res 22, 543–564 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-016-9317-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-016-9317-y

Keywords

- Corruption

- Corruption changes

- Corruption control indicator

- Corruption perception index

- Cross-border bribes

- Public administration corruption index