Abstract

This article examines consumer policy in 28 EU Member States. It introduces a new methodological framework and several indicators to analyse legal, social, enforcement, and associational dimensions of consumer policy. Drawing on the most recent data, the empirical results provide a detailed picture of consumer policy across Europe displayed in several indices. The results furthermore allow for statistically testing consumer policy regimes, as suggested by previous research. These indices reveal great differences between individual countries but only few instances of statistically significant differences between consumer policy regimes. Considering legal and political accounts as well as sociological explanations that have not yet been applied, possible explanations for these findings are discussed. It is concluded that comparative consumer policy analysis should further analyse differences between individual European countries in several dimensions and should not only account for consumer policy regimes from a legal or a political science perspective. The methodological framework and the theoretical explanations outlined in this article may help to accomplish this goal.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

For almost three decades, consumer policy in EU Member States has been strongly influenced by European consumer policy. Through many consumer policy directives, the European Commission has defined minimum requirements of consumer protection across Europe. Early and widespread directives, such as the Unfair Contract Terms Directive of 1993, the Price Indication Directive of 1998, or the Consumer Sales and Guarantee Directive of 1999, used a minimum harmonization approach that defined a threshold of consumer protection but left many options for national specification. More recently, European consumer policy has been characterized by maximum harmonization directives that aim to fully harmonize national models of consumer law throughout the Union (Collins 2005; Tonner 2014). An example of this trend is the Unfair Commercial Practice Directive of 2005 or the Consumer Rights Directive of 2011, which both provide only a few national deviation options. Although these directives have narrowed the Member States’ available options for setting their own consumer policy, they still leave some possibilities for the Member States to go further in their national level of consumer protection. Consequently and notwithstanding the efforts of the European Commission to align consumer protection in the Member States, current research has shown that national consumer policy approaches still differ (Cafaggi and Micklitz 2009; Repo and Timonen 2017; Wind 2016).

Comparative studies of consumer policy in Europe have used a regime approach in seeking to identify similarities and differences of consumer policy models between groups of countries (Cafaggi and Micklitz 2009; Cseres 2005; Micklitz 2003; Repo and Timonen 2017; Trumbull 2006a, b). Despite different research interests and scientific perspectives, all of these studies found consumer policy regimes, such as a Scandinavian regime consisting of Denmark, Finland, and Sweden or an East European regime consisting of all East European Member States. Considering the efforts of the European Commission to align consumer policy throughout the Union, such findings are notable. However, given that the enforcement of consumer rights is still a national task (Cafaggi and Micklitz 2009) or that collective actors have different interests in consumer policy-making (Trumbull 2006a), these findings are not surprising. Instead, what is surprising is that to distinguish and explain consumer policy models, previous studies selected only a few dimensions and factors, such as enforcement regimes (Cafaggi and Micklitz 2009), legal traditions (Micklitz 2003), or consumer policy-making (Trumbull 2006a, b). They mainly used literature reviews (Repo and Timonen 2017) or case studies of selected countries (Cafaggi and Micklitz 2009; Cseres 2005; Trumbull 2006a, b) for their analyses and conclusions. Finally, the effect of European Consumer Policy Directives and their specific application by Member States has not yet been considered to account for the different levels of consumer protection in European Member States.

This article introduces a new methodology to comparatively study consumer policy in 28 EU Member States and tests previous regime approaches. The methodological framework combines legal, political, and sociological arguments to distinguish four relevant dimensions of consumer policy: A legal, an enforcement, and an associational dimension of consumer policy, suggested by a previous work, as well as a social dimension that has not so far been considered. By using several new indicators and recent secondary data for measurement, an index of consumer protection in each dimension is outlined. These indices allow for a fine-grained and detailed picture of consumer policy in the 28 EU Member States. Drawing on the numeric index values revealed, non-parametric tests are used to statistically examine consumer policy regimes suggested by previous research.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: Section one reviews previous comparative research on consumer policy in Europe. Section two introduces the methodological framework and the data and methods used to analyse consumer policy. Section three presents the results of the empirical analysis. The last section summarizes and discusses some explanations of the findings and argues for a more fine-grained theoretical and methodological framework for analysing consumer policy in EU Member States. As only some previous explanations of different levels of consumer protection help to interpret the findings revealed in this article, further theoretical analyses are suggested to better account for different levels of consumer protection in Europe and elsewhere.

Comparative Consumer Policy Analysis—Regimes as State of the Art?

Previous research has only scarcely analysed consumer policy in Europe from a comparative perspective. Existing studies have either compared aspects of the general institutional approach of consumer policy (Repo and Timonen 2017; Trumbull 2006a, b) or specific areas of consumer policy such as consumer law (Cafaggi and Micklitz 2009; Cseres 2005; Hodges 2008; Micklitz 2003).

Legal studies have been mainly interested in consumer rights before a court and in their enforcement (Cafaggi and Micklitz 2009; Cseres 2005; Hodges 2008; Hodges et al. 2012; Micklitz 2003; Micklitz and Wechsler 2016; Weber 2016). Micklitz (2003) presented an early conceptualization of different law traditions in Europe (see also Reich and Micklitz 1980). Although his seminal work focused on consumer law in the 1970s, it is still widely used to account for legal differences as a main dimension of consumer policy in Europe today (e.g., Benöhr 2013; Cseres 2005; Repo and Timonen 2017). Micklitz presents four distinct consumer law traditions and associated “models”: a Scandinavian, a German, a Romance, and a Common Law model (Micklitz 2003, pp. 1046–1048; similarly, Cseres 2005, pp. 159–166). These models are differentiated by analysing two dimensions. The first dimension is composed of the main instruments used to protect consumers, as follows: a “sophisticated system of legal provisions under the control of a consumer ombudsman” in Scandinavian countries; the “control of standard business conditions” in the German model; “consumer information and consumer contract law” in the Roman model; and “product security and competition law” in the Anglo countries. The second dimension is composed of the main actors that enforce consumer rights, as follows: ombudsmen in the Scandinavian and common law models, public authorities in the Roman law model, and consumer associations in the German model.

A similar reasoning is found in more recent and more fine-grained comparative legal analyses which distinguish between consumer law and its enforcement as dimensions of consumer policy (Cseres 2005; Hodges 2008; Cafaggi and Micklitz 2009). For example, Cafaggi and Micklitz (2009) differentiate EU Member States’ enforcement regimes by using two indicators: the opportunities of group actions and the institutional approach of enforcing such actions. In summary, they found main differences between Scandinavian and East European countries. The former group is characterized by strong public authorities to enforce consumer rights, especially Ombudsmen (Cafaggi and Micklitz 2009, p. 426), and grants standing to consumer associations before a court (Cafaggi and Micklitz 2009, p. 423). The latter is characterized by both weak public authorities and weak consumer associations (Cafaggi and Micklitz 2009, pp. 420, 423). Regarding continental or Southern European countries, the picture is less clear. Although their comments on “the new democracies” are few, the authors suggest that Southern European countries have built another distinct regime characterized by linking consumer policy to broader public political concerns (e.g., Cafaggi and Micklitz 2009, pp. 419–420). For the continental European countries, there seems to be no straightforward answer, as the authors show both commonalities and differences in the “public-private-mix” of enforcement. However, consumer organizations in Germany and Austria as well as the Netherlands were identified as playing a rather strong role in consumer policy, and those in France were identified as moving closer to the “Austrian/German approach” (Cafaggi and Micklitz 2009, p. 423). Returning to Micklitz’ (2003) suggestion of distinguishing legal traditions of consumer law in the 1970s, note that Cafaggi and Micklitz somehow confirm this older classification by clearly distinguishing a Scandinavian and a German regime. Their analysis furthermore widened Micklitz’ initial account by suggesting an Eastern European regime of consumer law enforcement (similarly, Cseres 2005).

Finally, similarities and differences in consumer law have recently been analysed by Goanta (2016). A particularity of her study is that she compares Belgium, Ireland, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Romania, and the United Kingdom (UK based on a “numeric” comparative law approach.Footnote 1 Like the approach used in this article, she uses several indicators to measure the transposition of five consumer directives by means of an additive index (Unfair Contract Directive; Doorstep Selling Directive; Distance Selling Directive, Consumer Sales Directive, Unfair Commercial Practice Directive). This “convergence index” is informed by desk research considering substantive and procedural decisions by national courts and legislators regarding the analysed directives between 1985 and 2005 (the “institutional design” in each year; Goanta 2016, p. 275). Her first finding is that the level of convergence, the “harmonization process,” follows a different temporal pattern since decisions of national legislators either favoured or hindered the transposition of the analysed directives—a “j-shaped distribution” in Germany and the Netherlands where convergence first declines and then steadily increases; a “w-shaped distribution” in the UK, France, and Belgium where convergence slight decreases, briefly increases and suddenly decreases again; and a “uniform-distribution” in Ireland where the transposition of all directives follows an “upward slope” (Goanta 2016, pp. 275–279). A second finding is that the “level of convergence” differs substantially between the seven analysed countries in 2005: Ireland and the UK score most convergence “index points,” “closely” followed by Germany and Romania, and by France and Belgium. The Netherlands “lagged behind” (Goanta 2016, pp. 292–294). Overall, Goanta further confirms that “certain Member States can indeed be grouped or they manage to set themselves apart from the rest of countries” (Goanta 2016, p. 293).

It is the merit of Goanta’s study to enrich comparative legal studies by using a numeric, not a substantive approach comparing some EU Member States in terms of their legal consumer protection framework. Yet, it is questionable why she measures “convergence” against the background of what the “European Commission had in mind” when defining the relevant directives. Consequently, her research design explores the differences between European Member States legislative designs in terms of the Commission’s intention while neglecting the use of options within these directives to enhance consumer protection. Hence, she fails to provide an answer to the question which legal design protects consumers most and which is the level of legal consumer protection to date.Footnote 2

In analysing consumer policy, the previously mentioned legal studies mainly focus on consumer law and its enforcement before a court as two relevant dimensions to distinguish consumer policy in the European Member States. However, they miss some important aspects, for example, the broader consumer policy framework and the role of different actors in policy-making to distinguish consumer policy in the EU Member States. Such aspects were analysed by Gunnar Trumbull in his well-acknowledged consumer capitalism approach (Trumbull 2006a, b). This approach is also an example of a political science perspective on consumer policy (Strünck 2005; Vogel 2012; see Nessel 2016a, 2017). Trumbull’s main argument is that different consumer policy organizations are closely intertwined with specific ideas about consumers and markets (e.g., Trumbull 2006a, pp. 15–27). He distinguishes between the concept of consumers as “political” or “economic citizens” and that of consumers as an “interest group.” Regarding ideas about the so-called market problems, he distinguishes between “inadequate rights,” “market failure,” and the “need for negotiation.” Building on these dimensions, Trumbull argues that ideas foster corresponding consumer policy regimes, such as the following: in France, Belgium, or Luxembourg, a “protection model” where consumers are seen as political citizens with inadequate rights; in Germany and Great Britain, an “information model” based on the idea of consumers as economic citizens and the need to resolve “market failures” by enhancing consumer information; and in Scandinavia, a “negotiation model “built on the idea of consumers being part of an “interest group” that should have the right to directly negotiate with producers via dedicated forums such as ombudsmen (see also Trumbull 2006b). Each of the three models is associated with specific institutional arrangements: the “negotiation” or “associative model” established a consumer ombudsman system, dedicated “market courts” to “manage consumer legal cases” and “informative product labelling” (Trumbull 2006b, p. 83). The “information model” fostered institutions that should provide and enhance (independent) consumer information through “consumer advice centres,” “comparative product testing organizations,” or “standardization institutes” (Trumbull 2006b, p. 84). The political model banks on a “strong monitoring and policy role for the courts and the state” and on “Consumer Safety Commissions” with “extraordinary powers to block products from being put on the market and to recall products that are already in the shelves.” (Trumbull 2006b., p. 85) According to Trumbull, it is particularly the specific power relations between collective actors that lead to specific institutional arrangements of consumer policy. For example, he argues that the combination of rather strong consumer organizations and rather weak business interests led to the French “protection model.” In comparison, rather weak consumer organizations and rather strong business organizations fostered the German “information model” (Trumbull 2006b, pp. 20, 49–52).

Most existing studies of consumer policy in Europe either use a legal or a political science account to argue for consumer policy regimes. An exception is the study by Repo and Timonen (2017) that combines both perspectives. This study is furthermore innovative because it tries to statistically test the outcomes of consumer policy regimes. Merging the suggestions of Trumbull (2006b) and Micklitz (2003) as well as the European Union’s distinction of countries in a spatial (North, East, West, South) perspective (EU 2017a), they suggest five consumer policy “regimes”: An “Anglo” (Cyprus, Ireland, Malta, UK), a “Continental European” (Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Luxembourg, Netherlands), an “Eastern” (Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Lithuania, Latvia, Poland, Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia), a “Scandinavian” (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden), and a “Southern European” regime (Greece, Italy, Portugal, Spain). These regimes are named “geographically with the exception of the Anglo regime, which is named according to legal tradition” (Repo and Timonen 2017, p. 130).

After having theoretically deduced five consumer policy regimes, Repo and Timonen set out to statistically test whether these perform differently in “market performance.” To do so, they used data provided by the European Commission’s Market Performance Index (MPI) that compares 50 consumer markets in four dimensions (“comparability of goods and services,” “trust in retailers or suppliers,” “consumer complaints,” and “consumer satisfaction”). The authors decided to use 10 markets for further analysis: small household appliances, large household appliances, other electronic products, fuel for vehicles, meat and meat products, bank accounts, internet provision, electricity services, second-hand cars, investments, pensions, and securities. Their initial results show “statistically significant differences in MPIs in seven out of 10 markets” (Repo and Timonen 2017 p. 136). However, post hoc tests only found “statistically significant differences in five [out of ten] markets” (Repo and Timonen 2017). Interestingly, the authors understand this result as supporting their argument of varying consumer policy regimes in Europe. However, a pairwise comparison of regimes showing significant results in only five out of ten markets may question this interpretation. It is also questionable why they did not present the exact results of post hoc tests that would have shed light on the questions regarding which regimes statistically differ and how strong the effect sizes are (e.g., with Cohen’s d; see below).

In summary of the argument presented so far, most existing studies that have comparatively analysed consumer policy across Europe either followed a legal or a political science perspective. The former focuses on consumer rights before a court and their enforcement; the latter on further aspects of consumer policy, such as the provision of consumer information or the role of business and consumer associations in policy-making. Both perspectives and associated studies have argued for the existence of consumer policy regimes. The same is true for the study by Repo and Timonen (2017) that merges both perspectives. Notably, only a few legal studies have used more recent data for conclusion (Cafaggi and Micklitz 2009; Cseres 2005; Goanta 2016). Instead, Trumbull’s approach, which is an example of a political science perspective, is based on data no later than the early 1990s. While all previous studies relied on literature reviews and/or case studies of selected countries, Repo and Timonen were the first to statistically test the performance of previously suggested consumer policy regimes. However, their analysis left more questions than answers regarding the existence of potential consumer policy regimes and the differences between them. Another shortcoming of previous studies is that they failed to take European Consumer Policy Directives into account to make sense of and explain possible consumer policy regimes or, at least, distinguish individual countries. An exception is the study by Goanta (2016) who introduced a numeric approach to compare the transposition of selected directives in seven Member States, but without examining the level of legal consumer protection in these countries. Finally, previous studies selected only few dimensions to distinguish consumer policy in the EU Member States. To date, the legal and political science perspectives and the legal, the enforcement, and the associational dimensions have been examined to distinguish countries in terms of their consumer policy framework, stand unconnected side by side. In the following, this article tries to address some of these gaps by introducing a more fine-grained methodology which combines several perspectives and dimensions and by using most recent data to offer a new way to analyse consumer policy in the EU Member States.

Methodology, Data, and Methods to Analyse Consumer Policy in EU Member States

This article introduces a new methodological framework to analyse consumer policy in the 28 EU Member States. This framework encompasses four central dimensions of consumer policy: the legal, the social, the enforcement, and the associational dimension. It is based on and brings together legal, political, and sociological accounts of consumer policy as well as a range of individual studies which are unconnected until now. As will be shown in the next section, this framework allows for a more detailed picture of consumer policy in the 28 EU Member States than individual approaches considering only few dimensions or countries. In what follows, each dimension as well as the associated subdimensions, the indicators, and the data used for measurement are justified. Finally, the methods used to analyse consumer policy in EU Member States are presented.

The Legal Dimension of Consumer Policy

Consumer policy is inextricable linked to consumer law. This is because the evolution of consumer policy has gone hand in hand with the definition and expansion of consumer rights, in the European Union (Benöhr 2013; Tonner 2014; Weatherill 2013) as elsewhere in the world (see the contributions in Micklitz and Saumier 2018a). Until today, “consumer policy has mostly been protection by law” (Strünck 2005, p. 736). On the one hand, consumer law grants consumers substantive legal rights against sellers. On the other hand, it obliges sellers to adhere to a set of rules in market transactions (see below). Consequently, consumer law and consumer rights are a main element of consumer policy acknowledged by legal scholars (see Micklitz and Saumier 2018b for a recent overview) as well as by political scientists (Strünck 2005; Trumbull 2006a, b; Vogel 2012). Moreover, since the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, which was adopted in 2000, the provision of “fundamental [consumer] rights are having an increasing impact on consumer protection, playing a growing role in EU and Member States’ law” (Benöhr 2013, p. 46).

The legal dimension of consumer policy acknowledges that consumers’ rights are one important dimension of consumer policy. This article uses four sometimes overlapping European directives as subdimensions for measuring this subdimension: The Unfair Contract Terms Directive of 1993 (UCTD), the Price Indication Directive of 1999 (PID), the Consumer Sales and Guarantees Directive of 1999 (CSGD), and the Unfair Commercial Practice Directive of 2005 (UCPD).Footnote 3 Altogether, these directives cover all stages of consumer-producer relations: the pre-contractual, the contractual, and the post-contractual stage (EU 2017a). More precisely, they cover consumer information requirements (PID and UCPD), marketing and selling practices (UCPD), contract law (UCTD), and consumer redress or consumer guarantees (CSGD). The PID and the UCPD are examples of the pre-contractual or pre-purchasing stage directives. The former stipulates the “indication of the selling price and the price per unit of measurement of products offered by traders to consumers in order to improve consumer information and to facilitate comparison of prices.” (PID 1999, Art. 1) Its scope includes all products but no services and all businesses excluding “small businesses.” The latter establishes “uniform rules to govern all marketing practices, which are designed to induce consumers to purchase goods and services, controlling misleading advertising, false claims about products and services, deceptive pricing, high pressure sales techniques, and similar sharp practices” (Collins 2005, p. 90). However, it does not cover financial services or immovable property.

The UCTD is an example of a contractual stage directive. It protects consumers against unfair terms in standard, not individually negotiated, contracts. To determine if a term is “unfair,” it suggests a non-exhausted list of unfair terms in its original Annex. As the listed terms in this Annex are not legally binding but only a suggestion to be further determined, the UCTD leaves the option to introduce a nationally binding “blacklist” of terms considered unfair in all circumstances or a “greylist” of terms presumed to be unfair unless proven otherwise (EU 2017a, pp. 76–80). Finally, ensuring that a “promised” quality or functioning of a product is sustained over a certain time span, the CSGD is used to measure the post-contractual or post-purchasing stage. It mandates a “two-year legal guarantee period that makes the seller liable for any defect in goods that existed at the time of delivery and becomes apparent within two years” (EU 2017b, p. 9). If consumers detect defects in consumer goods, the directive entitles them to claim remedies within a certain period: Within the first six months after purchase, it is the seller who must prove that a defect did not exist at the time of delivery (“burden of proof period”); afterwards, the consumer must prove that a defect exists. As each directive provides some minimum requirements that EU Member States cannot undercut but can exceed, the most relevant available options that Member States can pursue in their national level of consumer protection are used as indicators to measure their performance for each subdimension (see Table 1).

As displayed in Table 1, with two exceptions, the indicators or potential options within the directives discussed before are weighted equally. This is because all indicators are suggested to be equally important from a consumer perspective, as they either extend the scope of the associated directives to relevant consumer markets not covered by these directives (PID, UCPD) or because they substantially extend the consumer rights against sellers. The different weighting of the consumer contract law indicators is based on the justified assumption that blacklists of unfair terms may become more relevant in front of courts than terms specified in greylists and hence will protect consumers better (EU 2017a, p. 78/79). Countries with a blacklist are therefore assigned 2 index points, and countries with a greylist assigned 1 index point. The different weighting of the consumer redress/guarantee subdimension indicators considers the differences to ensure the guarantee of products (see “Descriptive Results Examining Consumer Policy in EU Member States”). Countries with a guarantee period covering the life span of a product are assigned 2 index points. Countries exceeding the two-year guarantee period provided for by the CSGD but having introduced a ceiling of product liability are assigned 1 index point. Both procedures allow for considering relevant differences in both subdimensions. However, as this weighting of the indicators may give reason for criticism, the statistical section of this paper tests alterative explanations of the indicators without weightings.

The data used to measure the first three subdimensions is retrieved from the “Fitness Check on Consumer and Marketing Law,” a study conducted by Civic Consulting for the European Commission in 2016 (EU 2017a). This study analysed the state of transposition of the UCTD, the PID and the UCPD in all European Member States. The results are presented in a 460-page summary report and provide a detailed country analysis of approximately 1300 pages. The report uses the following data and methods: a legal analysis in each country prepared by at least one legal expert; a literature review of the existing studies analysing consumer law in each country; a total of 243 interviews with national and European consumer associations, public authorities and political actors; an open consultation receiving 436 questionnaires; and a stakeholder consultation to discuss initial results and final interpretations. The data used for measuring the transposition and the use of options within the CSGD is retrieved from an additional study, which was also a part of the “Fitness Check,” that relied on a similar methodology and similar methods (EU 2017d).Footnote 4 Although the data provided in the Fitness Check study may have some limitations, it is the only study that comparatively investigated the implementation of relevant European consumer directives in all 28 European Member States. As it furthermore uses a rigorous methodology, the data provided by this study is used as the main source to explore the legal dimension of consumer policy, enriched and cross-checked by my own additional desk research.

The Social Dimension of Consumer Policy

With only one exception, namely, the UCPD, the European consumer policy directives, do not furthermore distinguish between consumers defined as “average” and those with special needs, the so-called “vulnerable consumers.”Footnote 5 Hence, together with the legal dimension of consumer protection outlined before, these directives do not include a social dimension giving special attention to consumer groups that may be more vulnerable than others (e.g., children, the elderly, the disabled, the socially deprived, or the illiterate). However, consumer policy also includes social or welfare policy elements acknowledging and addressing the need of vulnerable consumer groups (see, e.g., the contributions in Bala and Müller 2014 and in Hamilton et al. 2016). Today, the vulnerable consumer has “entered the scene in consumer law” (Tonner 2014, p. 706) as well as in consumer policy more generally (see Bartl 2010 and Cartwright 2015 in this Journal). Consequently, “vulnerable consumer protection” has led to policy programmes in many EU Member States (Bartl 2010) as well as in the European Commission (EU 2017c).

This article addresses Member States’ policy responses to tackle consumer vulnerability in the social dimension of consumer policy. Given the wide scope of possible measures to tackle consumer vulnerability, such as by means of law (Tonner 2014), informational policy (Cartwright 2015) or subsidies (Bartl 2010), exploring this dimension is a challenging task. It is more so because comparative data on this issue for all EU Member States was only once collected in a study for the European Commission (EU 2017c). As the methodology and the methods used in the European Commission’s study on consumer vulnerability are both rigorous and well suited for examining the Member States’ policy accounts to tackle consumer vulnerability, this article uses its results and indicators as a proxy to measure the social dimension of consumer policy. In doing so, the results of this article allow for a comparative comparison of individual countries regarding their “social consumer protection,” a perspective which is missing so far in previous research.

The indicator “overall strategic approach” reflects if “consumer vulnerability is present in legislation and [in] the overall consumer protection policy.” (EU 2017c, p. 375) It hence follows the ideas of legal scholars (e.g., Tonner 2014) and social scientists (Hamilton et al. 2016) in that sensitizing policy- or lawmakers for the concept of the vulnerable consumer is a first step to implement a social element into consumer policy approaches. The indicator “sector-specific measures against vulnerability” considers policy measures in three exemplary and important economic sectors (telecommunications, energy and finance; see Bartl 2010; Cartwright 2015). Such sector-specific measures include reduced tariffs for vulnerable consumers in the telecommunication and energy sectors and special loans in the financial sector as well as a range of other measures (e.g., the right to a bank account or to an energy supply and broadcasting, as well as in case of outstanding bills). They are one way for “the State to provide or subsidize essential goods and services” by means of “social funds” (Cartwright 2015, p. 135). Such a social “fund includes both a regulated scheme, which provides grants such as […] cold weather payments (which do not have to repaid), and a discretionary scheme, which provides budgeting loans (which are repayable but interest free) (Cartwright 2015; see also Bartl 2010).

The data for assessing the social dimension of consumer policy results are based on “[scientific] expert and stakeholder interviews [e.g., with consumer organisations], and secondary research (e.g., strategy documents, websites of relevant authorities or consumer organisations, identified literature)” (Cartwright 2015 p. 408) outlined in the European Commission’s study on consumer vulnerability. After a thorough analysis of the results presented in the country fiches that, in case of doubt, were counter checked by my own desk research, I only suggest two modifications of the assignment of countries to the suggested indicators. The first is not to assign Romania to the group of countries with a broad strategic approach because the existence of consumer associations stated in the report (Cartwright 2015, p. 523) and in other research (Murafa et al. 2017) does not support this classification. The second is to assign Denmark to the group of countries with a broad strategic approach. In the Danish case, again, the country’s fiche (EU 2017c, pp. 426–427) support this view.

The two indicators are weighted differently because consumers may benefit more from sector-specific policy measures that immediately improve their financial (e.g., reduced tariffs) or social situation (e.g., the right to a bank account or to an energy supply and broadcasting, as well as in case of outstanding bills) than from a broad policy strategy that may only potentially improve their standing before the court or in policy (in the future). But again, the statistical section of this paper tests alterative explanations of the indicators without weightings. Table 2 displays the subdimension and indicators that measure the social dimension of consumer policy.

The Enforcement Dimension of Consumer Policy

Consumer law and legislative measures to protect consumers are a central dimension of consumer policy. However, consumer protection must not only be present in theory but also enforced and monitored (Cafaggi and Micklitz 2009; Micklitz and Saumier 2018b). The enforcement dimension is therefore another important dimension of consumer policy and is explored in this study. Consumer protection may benefit consumers and become effective only if firms respect consumer rights and refrain from practices to the detriment of consumers. As firms are the target of consumer law and legislation enforcement, this study therefore takes the firms’ perceptions of the monitoring and enforcement of consumer rights by public as well as by private actors as a proxy to measure this dimension. In this vein, this study differs from legal studies that have analysed the institutional organization of enforcement without empirically analysing the possible effects of enforcement on firms (see Micklitz and Saumier 2018b, p. 5). It furthermore differs from legal studies in acknowledging that it is not only public authorities or law that influence the adherence of consumer rights but also private organizations. By including private actors, such as consumer associations (Nessel 2016a), the media (King and Pearce 2010), or self-regulating industry bodies (OECD 2015) as a relevant factor for the firms’ compliance with consumer law and legislation, this article follows sociological suggestions that see such actors as important “watchdogs” of firms and relevant for their behaviour (King and Pearce 2010; Nessel 2012, 2016a, b, c).Footnote 6 Consequently, the firms’ perceptions of the monitoring and enforcement of their compliance with consumer protection by public as well as by private actors are taken as indicators to measure this dimension (see Table 3). The data for measurement is retrieved from the Consumer Condition Scoreboard on Retailers’ Attitudes towards cross-border Trade and Consumer Protection of 2016, which is based on 10 989 retailer responses throughout the Union (TNS 2016).

The Associational Dimension of Consumer Policy

The collective representation of consumers before a court and in politics has been defined by a variety of international organizations such as the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) or the United Nations as well as by many individual countries as another central consumer right. Collective consumer interests are usually represented by consumer associations. Consumer associations have been identified as important for the democratic representation of consumers in policy-making (Strünck 2005; Trumbull 2006a, b; Vogel 2012), in the legal arena (Cafaggi and Micklitz 2009; Micklitz and Saumier 2018b), and for the sound functioning of markets (Nessel 2016a, pp. 76–96, 2017). The right of consumers to be politically, legally, and economically represented by consumer associations is hence another important element of modern consumer policy. It is accounted for in the associational dimension of consumer policy.

This associational dimension should be examined by several subdimensions, including the financial, political or legal resources of consumer associations. However, there is no comparative data on these issues for all EU Member States. Due to this reason, this article uses another relevant indicator to measure the associational dimension of consumer policy: the symbolic capital of consumer associations. By symbolic capital, this article refers to the acknowledgement of consumer associations in the eyes of others in a Bourdieusian sense. More precisely, it conceptualizes the symbolic capital of consumer associations in the trust consumers bestow on them. This is because, from an associational perspective, it is important that consumers trust their representatives. Only when consumer associations can comprehensively claim that they represent the collective interests of most consumers will political actors acknowledge these associations as consumer representatives. Only then will these associations be granted legal rights and public funding. Finally, only when firms believe that most consumers trust in consumer associations will the consumer associations’ claims become relevant for the actions of firms (Nessel 2012, 2016a, b). As trust in consumer associations is the only available indicator to measure this subdimension in all Member States, it is used as a proxy to approach the associational dimension (see Table 4). The data for this assessment is retrieved from the Consumer Conditions Scoreboard on Consumer Attitudes towards cross-border Trade and Consumer Protection of 2016, which is based on approximately 28 000 consumer responses throughout the Union (EU 2017a).

Methods to Analyse the Four Dimensions of Consumer Policy in 28 EU Member States

The results in each dimension and the associated subdimensions are presented in the form of indices. The enforcement and the associational dimension indices use the numeric values of the associated survey questions in the studies from which the data for the measurement is retrieved. To formulate the legal and the social indices, the qualitative data retrieved from the associated studies are quantified according to the suggestions above. Although such quantification of qualitative data has some limitations and may suggest “sharper” differences than those potentially existing, this procedure has some advantages. This approach allows for a deeper statistical analysis that requires numeric values. Furthermore, by making the differences more visible, the quantification allows for better comparisons of consumer policies in EU Member States. Finally, the use of indices allows for numeric comparisons between individual countries applied in much comparative policy literature (see Esping-Anderson 1990 for a canonical argument on this point) and, most recently, in consumer law (Goanta 2016), but not yet in consumer policy analyses. The comparative approach used in this article is hence a first attempt to introduce a numeric, not a substantive comparison to analyse consumer policy approaches in several dimensions. This approach may be refined by future research considering several more indicators and dimensions (see “Discussion and Conclusion” section).

To test consumer policy regimes suggested by previous research, non-parametric statistical methods are applied. The Kruskal-Wallis test is used to statistically investigate previous suggestions of possible spatial or legal/institutional (Repo and Timonen 2017) regimes (see below). The Mann-Whitney-U test is used for testing temporal regimes (EU 15 vs. EU 13). In case these tests suggest differences between regimes, Cohen’s d is used for measuring effect sizes. Effect sizes below 0.1 indicate small effects, those below 0.3 indicate medium effects, and those above 0.5 indicate strong effects (Cohen 1992). In the following section, the descriptive results and the results of regimes tests are briefly discussed. The final section discusses and interprets the results in detail.

Descriptive Results Examining Consumer Policy in EU Member States

The Legal Dimension of Consumer Policy

Table 5 summarizes the results of all subdimensions measuring the legal dimension of consumer policy and displays the overall index points.

The results of the consumer standard protection index show that 11 Member States have formulated a blacklist and a greylist of terms that are considered or presumed to be considered unfair in standard contracts (3 index points; Austria, Cyprus, Estonia, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, and the UK). Eight have formulated a blacklist (2 index points; Belgium, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Greece, Latvia, Luxembourg, Malta, and Slovakia), and seven have formulated a greylist (1 index point; Croatia, Ireland, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, and Slovenia). Only the Scandinavian Member States, namely, Sweden, Denmark, and Finland, do not use a blacklist or a greylist of terms defined as unfair or presumed to be unfair (zero index points).

Regarding the two analysed regulatory options within the Price Protection Directive, the results of the associated price protection index show that only Malta and the Netherlands apply the PID to both services and small businesses (2 index points). Many Member States only use one of these two options: some apply the PID to small businesses but not to services (1 index point; Austria, Belgium, Germany, Greece, Lithuania, Slovenia, and the UK); others apply it to services but not to small businesses (1 index point; Portugal, Luxembourg, Latvia, Hungary, France, Denmark, and the Czech Republic). Interestingly, most Member States do not use any of the two options (Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, Ireland, Italy, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Spain, and Sweden; zero index points).

In the area of unfair commercial practice protection, most Member States, that is, 18 out of 28, do not use any of the options that go beyond the minimum requirements of the UCPD (zero index points). Only six member states apply the UCPD to both financial services and immovable property (2 index points; Denmark, France, Hungary, Malta, Spain, and the UK), and only another four apply it to either one of these areas (1 index point; Cyprus, Ireland, Netherlands, and Portugal).

Finally, the guarantee protection index shows that only five countries have extended the guarantee period as provided for by the CSGD (Finland, Ireland, the Netherlands, Sweden, and the UK). Interestingly, in Finland and the Netherlands, the guarantee period is related to the expected lifespan of a product (2 index points). Similarly, both Ireland and the UK have defined a ceiling of a six-year guarantee period (1 index point; see EU 2017d, p. 20). Furthermore, most Member States have not extended the burden of proof period—only France, Poland, and Portugal have introduced a longer period than the six months provided for by the directive (1 index point). In summary, most countries, that is, 20 out of 28, have neither an extended guarantee nor an extended burden of proof period that goes beyond the minimum requirements of the CSGD (zero index points).

If the index points in each subdimension are summarized as displayed in the additive legal protection index, the results show that the Netherlands and the UK score best (8 out of 10 possible index points). These countries strongly outperform Croatia, Romania, and Sweden (1 index point). Interestingly, most Eastern European countries score low (3 index points or below), with Hungary being an exception (6 index points); most Continental European countries have medium scores (2 to 4 index points), with France being an exception (7 index points). Most Southern European countries score medium to high (3 to 6 index points). From a temporal point of view, it is notable that EU 15 countries (4.5) score better on average than do the new Member States (2.8) and that the three best performing countries are found in the “old” Member States.

The Social Dimension of Consumer Policy

The results show that six out of 28 countries have in place a broad strategic approach in law and politics as well as a range of specific measures to tackle consumer vulnerability (3 index points; Denmark, Finland, Hungary, Ireland, Poland, and the UK). A total of 12 countries have a range of specific measures but no broader strategic approach (2 index points; Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Estonia, France, Greece, Italy, Malta, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain, and Sweden). Nine countries do not have any approach towards consumer vulnerability (zero index points; Austria, Croatia, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Romania, and Slovakia). Only the Czech Republic has a broad strategic approach to tackle consumer vulnerability but no sector-specific measures (1 index point). Table 6 summarizes these results in the vulnerable consumer protection index.

As the results show, only two Western countries (UK and Ireland) can be found in the group of countries scoring best in the social consumer protection dimension, and no Scandinavian or Southern country has a “poor” score. In a temporal perspective, on average, the EU 15 countries (1.7) perform slightly better than do the EU 13 countries (1.3). Seen form a spatial perspective, the Scandinavian countries perform best on average (2.67), followed by Southern (2.0), Western (1.5), and Eastern Member States (1.18). Applying a perspective that considers institutional and legal traditions (Repo and Timonen 2017), on average, the Scandinavian “regime” performs best (2.67), followed up by the Anglo (2.5), the Southern (2.0), the Eastern (1.18), and the Continental (1) “regime.”

The Enforcement Dimension of Consumer Policy

In the subdimension of public enforcement, the results show great differences between EU Member States. The firms’ rate of agreement that “public authorities actively monitor and ensure product safety and consumer rights in their sector” ranges from 51 to 89 index points in the subdimension of product safety and from 44 to 84 index points in the subdimension of general consumer legislation. In both dimensions, Poland performs lowest and Finland highest. In the area of product safety, more than 80% of the firms in Belgium, Finland, France, Hungary, Ireland, Luxembourg, and in the UK agree that “public authorities actively monitor product safety in their sector.” In Cyprus, Greece, and Poland, only 60% of firms agree on the relevant statement. Regarding consumer rights in general, more than 80% of the firms in Finland, France, Ireland, Luxembourg, and Malta agree that “public authorities actively monitor and ensure consumer rights.” In Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Cyprus, Greece, Poland Slovakia, and Spain, less than 60% of firms so agree. Table 7 displays the exact results.

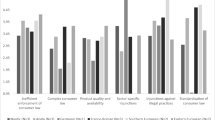

The public enforcement index of consumer protection incorporates both subdimensions of public enforcement, confirming the great differences in consumer legislation and law enforcement across Europe (see Table 7). The three best countries in this regard, Finland (177.8), France (172.3), and the UK (167), significantly outperform the three poorest countries in this regard, Poland (94), Greece (102.2), and Croatia (108.4). The results furthermore show that public enforcement of consumer legislations in general and product safety legislation in particular is higher in Western (average 156.5) and Scandinavian (average 153) Member States than in Eastern (average 131) or Southern (average 130.1) ones. Seen from the perspective of Repo and Timonen (2017), the average results show that Anglo (152.2), Continental (153.5), and Scandinavian (153) “regimes” strongly outperform Southern (125.7) and East European (131) “regimes.” From a temporal perspective, EU 15 countries score better (147.6) than do new Member States (129.4).

With regard to the enforcement and monitoring of consumer rights and legislation by private actors (private enforcement), the results again show strong variances (Table 8). Regarding the assessment of media regularly reporting on national businesses that “do not respect consumer legislation,” Bulgarian and Estonian firms perceive such surveillance most absent (41%), and Finish firms most strongly (79%) perceive such surveillance. Regarding firms’ perception of consumer associations that “actively monitor compliance with consumer legislation,” firms in Bulgaria and Estonia (41%) perceive such surveillance the least, and Finish firms have the strongest perception (79%) of this type of surveillance. Finally, 34% of Czech firms do not agree that “industry self-regulating bodies actively monitor respect of codes of conduct or practice in their sector,” while 81% of Irish firms do agree with this statement.

The composite private enforcement index shown in Table 8 incorporates all three subdimensions of the private monitoring of consumer legislation. It illustrates that the private enforcement of consumer legislations is generally higher in Western (average 189.4) and Northern Member States (average 181) than in Southern (average 165.2) or Eastern ones (average 140.6). From a temporal perspective, the EU 15 Member States score better on average (180.1) than do the new Member States (144.3). Analysed according to the suggested classification of Repo and Timonen (2017), on average, the Anglo (190.4), the Continental (183.6), and the Scandinavian (181) “regimes” outperform the Southern (160.7) and Eastern “regimes” (140.6).

The Total Enforcement Index incorporates the total public and private enforcement indices. The results of this index make the disparities in the enforcement in Member States even more clear. The firms in France (393.6) perceive the enforcement and monitoring of consumer rights and legislation almost twice as much as do the firms in Poland (216.1). Significant differences are also found between the firms situated in Belgium, Ireland, Finland, or the UK, which all score more than 360 index points, and those situated in Estonia, Slovakia, Latvia, Poland, Greece, Czech Republic, Croatia, or Bulgaria, which all score lower than 260 index points.

The Associational Dimension of Consumer Policy

The associational dimension of consumer policy is measured by the symbolic capital of national consumer associations or, more precisely, the trust of consumers in these organizations. As the results of the associational consumer protection index show, the consumers’ trust in consumer associations strongly varies. The index is the lowest in Greece (34.5), and the index in the UK (85.9) is more than twice that in Greece. Notably, in Austria, France, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Luxembourg, and the UK, more than 80% of consumers trust in consumer associations, while in Bulgaria and Greece, the rate is below 40% (see Table 9).

Seen from a spatial perspective, on average, trust in consumer associations is higher in Western (80.3) than in Northern Member States (62.5), and significantly higher in Western than in Southern (58.3) or Eastern ones (54.3). Seen from a legal/institutional perspective (Repo and Timonen 2017), the Western (78.9) and the Anglo (71.6) “regimes” outperform the Scandinavian (62.5), Southern (58.3), and Eastern (54.3) “regimes.” From a temporal perspective, the EU 15 Member States (68.9) outperform the new Member States (54.2).

Consumer Policy Regimes in Europe? Statistical Results

This section presents the statistical results of the Kruskal-Wallis (H) and the Mann-Whitney (U) test conducted to examine the European Union’s spatial and temporal classification of countries (EU 2017a) and Repo and Timonen’s (2017) suggestion of consumer policy regimes in a “legal/institutional” dimension. Cohen’s d is used to measure the effect sizes (see above). Table 10 presents the overall findings before the subsequent paragraphs display the results in detail.

The Legal Dimension of Consumer Policy

In the contractual subdimension, statistically significant differences between regimes from both a spatial (H = 13 663; p = 0.01) and a legal/institutional perspective (H = 14 218; p = 0.01) are found. Subsequent post hoc tests revealed differences between Northern and Western (p = 0.011; r = 0.99) and between Northern and Southern countries (p = 0.008; r = 1.01); differences were also found between a Scandinavian and a Western “regime” (p = 0.013; r = 1314) and between a Scandinavian and a Southern “regime” (p = 0.018; r = 1253). All effects are strong (r > 0.5). In a temporal dimension, no statistically significant differences between EU 15 and EU 13 countries are found (U = 78 000; p = 0.387). Interestingly, if the dimensions of this subdimension are not weighted as suggested in “Methodology, Data, and Methods to Analyse Consumer Policy in EU Member States,” similar results are found, that is differences between Eastern and Western countries (H = 11 191; p = 0.005; East-West: p = 0.030) as well as (H = 11 882; p = 0.08) between a Scandinavian and Southern “regime” (p = 0.016) and between a Scandinavian and a Western “regime” (p = 0.013). Similarly, in the temporal dimension, the weighting of the indicators of this subdimension does not change the results (U = 83 000; p = 0.538).

In the subdimension of price protection, no statistically significant differences between spatial (H = 4482; p = 0.225), legal/institutional (H = 6288; p = 0.177), or temporal regimes (U = 79 500; p = 0.413) are revealed.

In the unfair commercial practice subdimension, again, no statistically significant differences for a spatial (H = 5300; p = 0.140) or temporal regime (U = 75 500; p = 0.316) exist. In the legal/institutional dimension, the Kruskal-Wallis test suggested differences between regimes (H = 9028; p = 0.048) but post hoc tests did not confirm these results (p = 0.06).

Similarly, in the guarantee subdimension, no differences between spatial (H = 6881; p = 0.062), legal/institutional (H = 5541; p = 0.072), and temporal (U = 58 000; p = 0.72) regimes are found. Again, a different weighting of the indicators does not change the results in a temporal (U = 59 900; p = 0.08), spatial (H = 6167; p = 0.108), or legal/institutional (H = 4986; p = 0.288) perspective.

Finally, regime differences were analysed regarding overall legal protection as measured in the legal consumer protection index. For temporal regimes, no differences are found (U = 55 500; p = 0.052). For legal/institutional regimes, the Kruskal-Wallis test suggested differences (H = 13 845; p = 0.002), but a post hoc test did not confirm these (p values for all regimes above 0.05). Interestingly, statistically strong significant differences were found between an Eastern and a Western regime in a spatial dimension (H = 13 611; p = 0.01; post hoc p = 0.018; r = 0.68).

Similar results are found if the non-weighted indicators of the contractual and guarantee subdimensions are included into the overall legal protection index (temporal: U = 2500; p = 0.088; legal/institutional: H = 11 882; p = 0.008; p values for all regimes in post hoc tests > 0.05; spatial: H = 11 190; p = 0.005; East-West: p = 0.030; r = 0.644). Again, these results suggest that the before mentioned results including a weighting of different indicators are robust against alternative methodological considerations for measuring this subdimension.

The Social Dimension of Consumer Policy

In the social dimension, no differences between spatial (H = 4813; p = 0.19) or temporal regimes (U = 77 500; p = 0.363) were revealed. After controlling for differences in post hoc tests, the same was true for legal/institutional regimes (H = 10 454; p = 0.019; p for pairwise comparisons > 0.05). These results are confirmed by tests without a weighting of the indicators in the spatial (H = 4363; p = 0.229) and the temporal dimension (U = 5000; p = 0.857). Interestingly, a different weighting of the indicators in the legal/institutional dimension first suggested differences (H = 10 129; p = 0.024), but post hoc tests did not confirm these (p > 0.05). Again, these results further underline that a different weighting of the indicators does not change the overall results and they confirm the robustness of the results.

The Enforcement Dimension of Consumer Policy

In the public enforcement subdimension, differences were found between an Eastern and a Western regime in a spatial perspective (H = 10 865; p = 0.012; pairwise p = 0.021) and between EU 15 and EU 13 countries (U = 45.00; p = 0.015). The first effect is strong (r = 0.69), and the second is medium (r = 0.46). Even though differences were suggested by initial results (H = 9996, asymptotic p = 0.041), no differences were confirmed for legal/institutional regimes (p > 0.05 for all pairwise comparisons). In the private enforcement subdimension, similar results were found. Regarding spatial regimes, there are statistically significant differences between Eastern and Western countries (pairwise p = 0.03; H = 13 448, asymptotic p = 0.04). The effect is strong (r = 0.795). Differences between temporal regimes were also found (U = 32.00; p = 0.002). Again, the effect is strong (r = 0.57). In contrast with the public enforcement subdimension, in a legal/institutional perspective, the analysis (H = 3530; asymptotic p = 0.009) furthermore revealed differences between an Eastern and a Western “regime” (p = 0.046) as well as between an Eastern and an Anglo “regime” (p = 0.049). Both effects are strong (r = 0.687 and r = 0.726, respectively).

Regarding the overall enforcement of consumer protection, differences were found between Eastern and Western countries (H = 12 932, asymptotic p = 0.05; pairwise p = 0.04) and between EU 15 and EU 13 countries (U = 36 000; p = 0.04). Both effects are strong (r = 0.78 and r = 0.68, respectively). In the legal/institutional perspective, the initial results (H = 12 565; p = 0.014) were not confirmed by post hoc tests (p > 0.05 for all pairwise comparisons).

The Associational Dimension of Consumer Policy

In the Associational dimension, significant differences (H = 14 773; asymptotic significance p = 0.02) are found between Eastern and Western (p = 0.001) and between Southern and Western (p = 0.043) countries. Both effects are strong (r = 0.853 and r = 0.851, respectively). Similarly, from a legal/institutional point of view, statistically significant differences (H = 11 458; p = 0.022) were found between an Eastern and a Western “regime” (p = 0.017), and the effect is again strong (r = 0.761). Differences with a strong effect (r = 0.549) were also found between temporal regimes (U = 34 500; p = 0.003).

Discussion and Conclusion

This article examines consumer policy in 28 European Members States. It introduces a new methodological framework that encompasses four central dimensions of consumer policy: the legal, the social, the enforcement, and the associational dimension. This framework somewhat followed existing suggestions but extended these suggestions in several ways. This framework follows previous research based on legal and political science traditions by acknowledging consumer rights and their enforcement as well as by including associational aspects as relevant dimensions for analysing consumer policy (Cafaggi and Micklitz 2009; Cseres 2005; Micklitz and Saumier 2018b; Trumbull 2006a, b; Repo and Timonen 2017). In contrast with legal studies, however, the enforcement dimension does not analyse the institutional structure of the “public-private-mix” of enforcement (Cafaggi and Micklitz 2009). Instead, and following sociological suggestions, it approaches this dimension by using the perceptions of the targets of public enforcement, that is, the firms, as a proxy. Furthermore, the firms’ perceptions regarding the monitoring of consumer legislation by a range of private actors—consumer associations, the media, and self-regulating bodies—is analysed. This allows for approaching the enforcement of consumer protection not only by means of law but also by political (Trumbull 2006a, b) and social mechanisms (King and Pearce 2010; Nessel 2012, 2016a). In contrast with both political science and legal accounts, the associational dimension is measured by the consumers’ trust in consumer associations (“symbolic power”). This suggestion follows the sociological idea that the symbolic power of consumer associations is central for gaining access to policy-making and the legal arena, as well as for being acknowledged by firms (King and Pearce 2010; Nessel 2016a). The framework applied in this article furthermore encompasses the Member States’ approach to tackle consumer vulnerability and hence accounts for a social dimension of consumer policy neglected so far in comparative research (but see, e.g., for the UK, the contributions in Hamilton et al. 2016; for Germany, Bala and Müller 2014). Finally, the methodological framework defines clearly comprehensible indicators to measure the performance of each (sub)dimension of consumer policy.

Applying a fine-grained methodological framework and using most recent data, this article provides a current overview of consumer policy in the 28 EU Member States. The results are displayed in several indices. This procedure facilitates the presentation of numeric differences of consumer policies in EU Member States and the performance of statistical tests of the approaches of previous regimes. The results show great differences between individual countries but only few instances of consumer policy regimes. Regarding the legal dimension of consumer policy, the results show that possible options included in European Consumer Policy Directives are only used to some extent. As indicated by the associated legal protection index, the Netherlands and the UK score 8 out of 10 possible index points. Croatia, Romania, and Sweden score only 1 point, indicating that these countries only use one out of ten possible options provided to them under the scope of the directives examined. Most Eastern (3 index points or below) and Continental European countries (2 to 4 index points) do not achieve a medium score. They hence do not use a range of options as provided for by the analysed directives. Hungary (6 index points) and France (7 index points) are exceptions in this regard. The scores of the Southern European countries are mixed (3 to 6 index points).

Legal traditions represent one possible explanation of such differences (Cseres 2005; Micklitz 2003). However, as the results show, between countries, there are commonalities that are representative of different law models (e.g., in Belgium, Denmark, Estonia, and Italy), as well as differences associated with one model (e.g., in Denmark, Sweden, Finland). At least in regard to the use of possible options within the relevant European Consumer Policy Directives, the legal tradition explanation does not seem very explanatory. This interpretation is further supported by testing the differences between legal/institutional “regimes” (Repo and Timonen 2017). Significant differences between a Scandinavian and a Western “regime” and between a Scandinavian and a Southern “regime” are only found in the subdimension of consumer contract protection. Another possible explanation of differences in the legal dimension is the time of membership in the EU. Such an argument could assume that time of membership or institutional settlement (e.g., Meier 1987) would allow countries to become familiar with the organizational infrastructure of the EU and to employ staff with relevant skills to implement the European directives. However, such a rather organizational explanation is not very explanatory, as no statistically significant effect in any of the legal subdimensions is found between the EU 15 and the EU 13 countries. Finally, the different use of options provided for by the relevant directives could be traced to “interdependencies between the law, which transposes directives, and autonomous parts of national law” (Tonner 2014, p. 704). However, such an explanation could not be tested in this article because it requires a detailed analysis of the interdependencies of national and EU law in every aspect of law in a comparative manner. Such an account may however be considered by future research to explain the differences in consumer law as measured in this study.

As regards the social dimension of consumer policy, the analysis shows that 18 out of 28 European countries have a range of sectoral policy measures in place to tackle consumer vulnerability and that six furthermore have a broad institutional approach towards dealing with consumer vulnerability. Countries with no measures for handling consumer vulnerability are Austria, Croatia, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Romania, and Slovakia. How can this result be explained? One possible explanation is the existence in general of different institutional frameworks of welfare politics. Such an explanation would hold true in the case of the Southern European countries that all score above the medium score in this dimension and that are identified as having a rather broad and policy-oriented consumer policy approach (Cafaggi and Micklitz 2009, p. 419). However, following newer comparative welfare policy approaches in the tradition of Esping-Anderson (Arts and Gelissen 2002), most of these countries are from different “welfare regimes” (e.g., the regime in Austria and Germany is different from that in the East European countries). Another possible explanation for differences in this dimension is the assumption that more affluence leads to more expenditure for social protection (Meier 1987). Interestingly, however, two of the most affluent countries in Europe, Luxembourg and the Netherlands, do not have any approach towards consumer vulnerability, while Hungary and Poland, two “less affluent” countries, do have a broad strategic approach and a range of policy measures to tackle vulnerability. A temporal perspective is also inconsistent with such reasoning because no differences between EU 15 and EU 13 countries are found. Finally, no regime differences from a spatial and legal/institutional perspective are proven. Given such varying results, only further statistical analysis may finally prove possible explanations of these initial interpretations and consider more possible explanations (see below).

The results in the enforcement dimension show clear differences between Eastern and Western and between EU 15 and EU 13 countries. For example, the number of firms in France that perceive the existence of an overall enforcement and monitoring of consumer rights and legislation is almost twice as high as that in Poland. Strong differences are also found between firms situated in Belgium, Ireland, Finland and the UK and those situated in Estonia, Slovakia, Latvia, Greece, the Czech Republic, Croatia, and Bulgaria. Consequently, statistical tests revealed regime differences in a spatial and temporal perspective in the private as well as the public enforcement subdimension. These results fit well into existing studies that argue that East European countries are characterized by weak public authorities and weak consumer associations (Cafaggi and Micklitz 2009, p. 423; Cseres 2005). The results of previous research are also confirmed by using a more fine-grained analysis of private enforcement by consumer associations, the media, and industry self-regulating bodies. Notably, however, statistical tests in “legal/institutional regimes” suggested by Repo and Timonen (2017) confirmed differences only in the private subdimension of enforcement but not in the public subdimension or in the overall monitoring and enforcement dimension.

Finally, the results in the associational dimension show great differences between individual countries as well as between previously suggested regimes. Regime tests revealed strong differences in a temporal dimension. This result again fits well with previous research (Cafaggi and Micklitz 2009) and could be traced to the fact that consumer associations in Eastern Europe are much “younger” than their counterparts in the EU 15 countries. This interpretation also illuminates the significant differences between Eastern and Western regimes from a spatial as well as from a legal/institutional point of view and between Southern countries with rather young consumer associations and Western countries with well-established ones. In the associational dimension, hence, the “institutional settlement argument” (Meier 1987) proves to be a good explanation to interpret the results. As consumer associations also play a significant role in law enforcement (Cafaggi and Micklitz 2009), policy-making (Trumbull 2006a, b) and market arrangements (Nessel 2012, 2016a), varying levels of symbolic power of consumer associations may also explain differences in the enforcement dimension previously discussed. Consumer associations with high symbolic capital are mainly found in countries with high scores in overall enforcement (e.g., France, Ireland, the UK), and consumer associations with low symbolic capital in countries with low levels of enforcement (e.g., Bulgaria, Greece, Latvia). However, these results leave more questions for further research. Therefore, for example, differences in the associational dimension seem not to be associated with the right to claim group actions or the standing of consumer associations before a court. Trust in consumer associations does not seem to be associated with an “ombudsman system” in which consumer associations have no standing before a court or share a standing with strong public authorities. Sweden (50), Poland (66), and the UK (89 index points, respectively) are examples against a reasoning that may associate consumers’ trust in consumer associations with their court standing or with the organization of the “public private mix” in an ombudsman system (Cafaggi and Micklitz 2009).

Other possible explanations for different levels of trust in consumer associations could be associated with political science (Trumbull 2006a, b) or sociological approaches (Nessel 2012, 2016a, b). These approaches argue that consumer associations are not only relevant in consumer law enforcement or for claiming group action but also in consumer policy-making and for providing (independent) consumer information. However, such arguments would need further scrutiny, as no comparative study has ever analysed the political “power” of consumer associations (and against business “power”) or compared informational strategies of these organizations. Testing arguments such as the role of consumer associations in consumer policy is another task for future research to explain differences in the associational dimension as well as to explain the differences in the enforcement dimension (and perhaps the legal and social dimension as well).

Further research may evaluate more explanations and indicators to make sense of the differences revealed in this article regarding the consumer policies of EU Member States. Such explanations could benefit from existing political science or legal approaches. However, as the results of this article show, both perspectives only contribute to explain some differences between consumer policies in individual countries. Sociological or political economy approaches may furthermore be considered because they have proven useful to analyse consumer policy on a national scale (Nessel 2016a,pp. 76–96, b) as well as for explaining some results of this article. The same is true for studies which consider social or welfare policy arguments of consumer policy not yet applied in comparative consumer policy research (e.g., Hamilton et al. 2016). Moreover, several more indicators may refine the methodological framework suggested in this article. In the associational dimension, the legal or economic resources of consumer organizations could be considered to comparatively measure the power of the collective representation of consumers. In the social dimension, indicators may, e.g., consider how the special needs of vulnerable consumers are addressed in the legal arena and vis á vis firms. In the legal dimension, there is a need to not only consider the available options left by the discussed European directives analysed in his article, but furthermore selected national regulations which embed consumer-producer-relations. Finally, in the enforcement dimension, the “public-private mix” of enforcement (Cafaggi and Micklitz 2009) could further be refined by using a “numeric” approach as applied in this article and suggested by Goanta (2016) in case of consumer law harmonization. This approach could further include aspect such as the number of quality controls to monitor firm’s compliance with product safety or the level of penalty in case of infringements.

As regards regime approaches, this article revealed only few instances of consumer policy regimes, as suggested by previous research. This could be due to the methodology applied. This finding could also be due to the use of the only currently available comparative data on consumer policy. Finally, as said before, although representing a much more fine-grained methodology in contrast with previous research, statistically identifying only a few consumer policy regimes could be due to neglecting some consumer policy measurement indicators that have yet to be applied. Yet, as argued in this article, only a rigorous methodology and clearly defined dimensions and indicators for measurement, as well as recent empirical data, will provide a detailed picture of consumer policy in individual countries and shed light on possible consumer policy regimes. Future comparative consumer policy analysis may further refine the research agenda suggested in this article. Original data may further contribute to accomplish such a goal.

Change history

16 February 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10603-024-09560-3

Notes

In her study, Goanta follows recent developments in comparative law studies which apply a “quantification of law approach.” See the literature cited by her as well as https://www.cbr.cam.ac.uk/datasets/ as an example of such approaches.

In this vein, it is questionable why the analysed data in her doctoral thesis, published in 2016, are of no later than 2005. She (Goanta 2016, p. 38) acknowledges that the Consumer Rights Directive of 2011 has substantially changed some provisions of the analysed directives, but, due to the recent introduction of this directive, it has not been considered for further analysis. Interestingly, the same argument would hold true for her analysis of the Unfair Commercial Practice Directive which came into force in 2005, the year in which her numeric analyses ends.

Legal scholars may wonder why, even though it overlaps with and redefines some provisions of the directives discussed in this article, the Consumer Rights Directive (CRD) is not included in the analysis. However, compared to the elements in the directives used to measure the legal dimension of consumer policy in this article, most of the regulatory choices under the CRD do not substantively enhance consumer protection. This is certainly true for the following: Article 6 (7) that addresses “language requirements regarding the contractual information for distance and off-premises contracts”; Article 6 (8) on “additional information requirements regarding distance and off premises”; and Article 7 (4) that advises the trader “not to apply a simplified information regime for off-premises contracts to carry out repairs or maintenance.” Furthermore, Article 8 (6) that addresses “the introduction of specific formal requirements for contracts concluded by telephone” covers only a very few consumer contracts and is not generally applicable to most consumer contracts. Instead, Article 9 (3) and Article 3 (4) would be of more interest. The former provides the regulatory choice “to maintain, in the case of off-premises contracts, existing national legislation prohibiting the trader from collecting payment from the consumer during a given period after the conclusion of the contract”. The latter provides the option “not to apply the provisions to off-premises contracts if the payment to be made by the consumer does not exceed 50 euros.” However, as a comparative analysis of these latter two options left within the CRD show, there are only few differences between European Member States regarding the use of these regularly choices (EU 2017e, pp. 30–32). Another argument for not including the regulatory options chosen or not chosen by Member States as provided for by the CRD is, above all, the fact that the implementation of the legal requirements needs time for settlement (e.g., Meier 1987). As the implementation of the CRD was due on 13 Dec 2013 and given that some Member States have implemented the directive far later, a comprehensive analysis of its transposition may only make sense in the future (see also Goanta 2016, p. 38).

Notably, this additional study encompasses “stakeholder interviews” and “business surveys” only in selected countries (EU 2017d, p. 12).

Only some provisions provided for by the UCPD entail the notion of the “vulnerable consumer.” However, these have received reasonable criticism because of their vagueness and difficulties in transposition (e.g., Friant-Perrot 2016).