Abstract

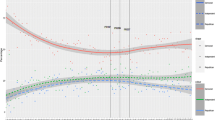

We evaluate the empirical effectiveness of de facto versus de jure determinants of political power in the U.S. South between the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century. Using previously-unexploited racially-disaggregated data on voter registration in Mississippi for the years 1896 and 1899, we show that the observed pattern of black political participation is driven by de facto disfranchisement as captured by the presence of a black political majority, which negatively affects black registration. The de jure provisions introduced with the 1890 state constitution and involving literacy tests and poll taxes exert a non-robust impact. Furthermore, a difference-in-differences approach shows that the decline in aggregate turnout pre-dates the introduction of de jure restrictions and confirms a causal effect of the presence of a black political majority. De jure restrictions intensify the influence of the latter after 1890, which suggests that the main effect of the constitutional reforms may have been an institutionalization of de facto disfranchisement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In 1860 there were fewer than 1000 free people of colour.

New qualifications for voters required that each elector (1) Be a male citizen; (2) Be 21 years of age or over; (3) Be a resident of the State 2 years and of the election district or municipality 1 year; (4) Be registered to vote; (5) Be not disqualified by reason of insanity, idiocy, or conviction of certain crimes; (6) Be able to read any section of the State Constitution, or be able to understand it when read to him, or to a give reasonable interpretation of it; (7) Have paid all taxes by February of the year in which he desires to vote and produce evidence of payment. This includes payment of an annual poll tax of two dollars.

In the Interrogatory Answers registration records are collected from registration books and complemented by additional information from poll books, poll tax receipts, poll tax payers lists, and application forms. Details are provided for each county.

Other general models of franchise extensions are proposed by Ades and Verdier (1996), Acemoglu and Robinson (2000), Bourguignon and Verdier (2000), and Lizzeri and Persico (2004), while Llavador and Oxoby (2005) and Galor et al. (2009) offer theoretical motivations for landowners’ opposition to democracy.

A distinction between informal and formal rules is applied by Carden and Coyne (2013) to the analysis of the race riots during Reconstruction, building on the theory of the stickiness of rules (Boettke et al. 2008). Accordingly, because of lower enforcement costs formal rules are more likely to stick when they are grounded in existing informal rules. In the context of race riots there was a disjuncture between the formal rules to protect blacks and the informal norms held by whites.

In contexts other than the U.S., Baland and Robinson (2008) look at the effect of the introduction of the secret ballot in Chile in 1958 to find that the change in political institutions had implications for voting behaviour, while for a sample of Latin American countries during the twentieth century Aidt and Eterovic (2011) show that the abolition of the literacy test increased redistributive policies.

In Mississippi the tax was cumulative, with a maximum total charge of four dollars. For the bottom three quarters of the southern population 1890 per capita income (including non-cash components) is estimated by Kousser 1974 at about 64 dollars.

See Harris and Todaro (1970).

See Irwin and O’Brien (2001) for migration patterns in the Mississippi Yazoo Delta in 1880–1910.

See the Report on Vital Statistics in the 1880 and 1890 census. See also Haines (2011) on the use of infant mortality as a proxy for economic and social conditions.

The latter consists of males over 21 years of age, with a few disqualifications, for instance in the case of felony.

See Vollrath (2013) for a detailed discussion on the link between our measure of land inequality, based on the distribution of farms by size, and wealth distribution in 1890.

Black registration is equal to the ratio of the number of registered blacks in 1896 and 1899 to black male population of age 21 and above in 1900 (the closest available year as in Kousser (1974). We proceed in a similar fashion for white registration.

In 1896 the total number of registered blacks and whites is 16,234 and 108,998, respectively. These figures are consistent with totals provided by the Biennial Report of the State Superintendent of Public Education to the Legislature of Mississippi (1897). The correlation between black registration in 1896 and 1899 is 93%.

The maximal white registration is above 100% because of frauds, which at the time were common in the South. For example Kousser (1974) reports that white registration in Louisiana in 1897 is 103.2%.

We use data on the share of literates in 1900 because figures for the adult population are available only for this year.

The index of sharecropping intensity is calculated as the ratio of farm population under a sharecropping scheme to total farm population. The index is equal to one if all farm population is under a sharecropping scheme.

The birth and death rates for 1880–1890 are provided by the Report on Vital Statistics of the 1890 census.

The number of blacks in Mississippi in the 1890 census is 742,559. However, if we augment the 1880 number of blacks by taking into account birth and death rates, we obtain an estimated number of blacks in 1890 of 747,835. We impute this difference to out-of-state migration.

If we take the difference between the share of blacks (including slaves and free coloured) in 1860 and the share of blacks in 1890 for the 60 counties that exist in 1860 we find that the increase in the share of blacks is 0.7%, which is larger than what previously reported in the text because of the creation of new counties from lands of pre-existing counties in the 1860s and the 1870s. We introduce our estimates of immigration because of the lack of comparability between the counties in place in 1860 and 1890.

In Quitman the bottomlands behind the riverfront were developed for cotton cultivation only in the late nineteenth century, causing a continuous increase in the population. Sizeable relocations of the black population were similarly present across other counties.

As a term of comparison, in 1890 la share of blacks over total population is 51.8%.

Data are from Project HAL: Historical American Lynching. We count all episodes of lynchings of blacks reported for the 1882–1896 period.

To compute land inequality we use the Generalized Entropy Index (a = −1).

We check for non-linearities by entering also the squared term of black adult male population, which however is not significant. We also replace black adult male population with slave population in 1860. The correlation between the two variables is 0.60 since the former excludes women and non-adult men (the correlation between the black share in 1900 and the slave share in 1860 is 0.95). Using the slave share reduces the number of counties to 60. Nevertheless results are similar. For brevity we do not report regressions for these checks.

We start from 1882 since lynching data are available since then.

Data for black adult male population are taken from relevant census years. The dummy for black political majority varies accordingly. Lynchings are counted for the 2-year period preceding each election. See Table 8 for data definitions and sources.

The post-constitution dummy is significant when we do not control for lagged turnout.

Despite the fact that in 2009 Congress voted to renew its validity until 2031, a 2013 Supreme Court decision struck down a key provision (Sect. 4), which involved a nearly-automatic obligation to obtain federal preclearance (Sect. 5) for any changes in electoral practices for jurisdictions that in the past used poll taxes and literacy tests.

References

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2000). Why did the West extend the franchise? Democracy, inequality, and growth in historical perspective. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115, 1167–1199.

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2008a). The persistence and change of institutions in the Americas. Southern Economic Journal, 75, 282–299.

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2008b). Persistence of power, elites, and institutions. American Economic Review, 98, 267–293.

Ades, A., & Verdier, T. (1996). The rise and fall of elites: A theory of economic development and social polarization in rent seeking societies. CEPR Discussion Paper no. 1495.

Aidt, T. S., & Eterovic, D. S. (2011). Political competition, electoral participation and public finance in 20th century Latin America. European Journal of Political Economy, 27, 181–200.

Alt, J. E. (1994). The impact of the Voting Rights Act on black and white voter registration in the South. In C. Davidson & B. Grofman (Eds.), Quiet revolution in the South: The impact of the Voting Rights Act, 1965–1990. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Baland, J. M., & Robinson, J. A. (2008). Land and power: theory and evidence from Chile. American Economic Review, 98, 1737–1765.

Bertocchi, G., & Dimico, A. (2011). Race v. suffrage: The determinants of development in Mississippi. CEPR discussion paper no. 8589.

Bertocchi, G., & Dimico, A. (2012). The racial gap in education and the legacy of slavery. Journal of Comparative Economics, 40, 581–595.

Bertocchi, G., & Dimico, A. (2014). Slavery, education, and inequality. European Economic Review, 70, 197–209.

Boettke, P. J., Coyne, C. J., & Leeson, P. T. (2008). Institutional stickiness and the new development economics. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 67, 331–358.

Bond, H. M. (1934). The education of the Negro in the American social order. New York: Prentice Hall Inc.

Bond, H. M. (1939). Negro education in Alabama: A study of cotton and steel. Washington: Associated Publishers.

Bourguignon, F., & Verdier, T. (2000). Oligarchy, democracy, inequality and growth. Journal of Development Economics, 62, 285–314.

Carden, A., & Coyne, C. J. (2013). The political economy of the reconstruction era’s race riots. Public Choice, 157, 57–71.

Cascio, E. U., & Washington, E. (2014). Valuing the vote: The redistribution of voting rights and state funds following the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129, 379–433.

Chay, K., & Munshi, K. (2011). Black mobilization after emancipation: Evidence from reconstruction and the great migration, mimeo. Brown University.

Clubb, J. M., Flanigan, W. H., & Zingale, N. H. (2006). Electoral data for counties in the United States: Presidential and congressional races, 1840–1972. Arbor: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research.

Filer, J. E., Kenny, L. W., & Morton, R. B. (1991). Voting laws, educational policies, and minority turnout. Journal of Law and Economics, 34, 371–393.

Galor, O., Moav, O., & Vollrath, D. (2009). Inequality in landownership, the emergence of human capital promoting institutions, and the great divergence. Review of Economic Studies, 76, 143–179.

Haines, M. R. (2011). Inequality and infant and childhood mortality in the United States in the twentieth century. Explorations in Economic History, 48, 418–428.

Harris, J. R., & Todaro, M. P. (1970). Migration, unemployment and development: A two-sector analysis. American Economic Review, 60, 126–142.

Irwin, J. R., & O’Brien, A. P. (2001). Economic progress in the postbellum South? African American incomes in the Mississippi Delta, 1880–1910. Explorations in Economic History, 38, 166–180.

Jones, D. B., Troesken, W., & Walsh, R. (2013). A poll tax by any other name: The political economy of disenfranchisement in the post-reconstruction South, mimeo. University of Pittsburgh.

Key, V. O. (1949). Southern politics in state and nation. New York: AA Knopf.

Kousser, J. M. (1973). Ecological regression and the analysis of past politics. The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 4, 237–262.

Kousser, J. M. (1974). The shaping of southern politics: Suffrage restriction and the establishment of the one party South, 1880–1910. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Lizzeri, A., & Persico, N. (2004). Why did the elites extend the suffrage? Democracy and the scope of government, with an application to Britain’s age of reform. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119, 707–765.

Llavador, H., & Oxoby, R. J. (2005). Partisan competition, growth, and the franchise. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120, 1155–1189.

Margo, R. A. (1982). Race differences in public school expenditures: Disfranchisement and school finance in Louisiana, 1890–1910. Social Science History, 6, 9–23.

Mississippi State Department of Education. (1897). Biennial report of the state superintendent of public education to the legislature of Mississippi. Jackson: State Printers.

Naidu, S. (2012). Suffrage, schooling, and sorting in the post bellum U.S. South. NBER working paper no. 18129.

Nunn, N. (2008). Slavery, inequality, and economic development in the Americas: An examination of the Engerman Sokoloff hypothesis. In E. Helpman (Ed.), Institutions and economic performance. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Ogden, F. D. (1958). The poll tax in the South. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

Redding, K., & James, D. R. (2001). Estimating levels and modeling determinants of black and white voter turnout in the South, 1880 to 1912. Historical Methods, 34, 141–158.

United States v. Mississippi. (1965). Interrogatory Answers, Archives and Special Collections, J.D. Williams Library. University: The University of Mississippi.

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. (1965). Voting in Mississippi. Washington: U.S. Commission on Civil Rights.

Voting Rights Act. (1965). Public Law 89–110. Eighty-ninth Congress of the United States of America.

Vollrath, D. (2013). Inequality and school funding in the rural United States, 1890. Explorations in Economic History, 50, 267–284.

Wharton, V. L. (1947). The Negroes in Mississippi 1865–1890. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank three anonymous referees and workshop participants at ECINEQ, Delhi Annual Conference on Economic Growth and Development, Asian Meetings of the Econometric Society, PRIN Workshop on Institutions, Social Dynamics and Economic Development, Singapore Management University, Tufts University, Boston University, New York University, Brown University, and USI Lugano, for helpful comments on previous drafts. Generous financial support from Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Modena and the Italian University Ministry is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bertocchi, G., Dimico, A. De jure and de facto determinants of power: evidence from Mississippi. Const Polit Econ 28, 321–345 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10602-017-9239-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10602-017-9239-9