Abstract

The finance sector’s response to pressures around climate change has emphasized disclosure, notably through the recommendations of the Financial Stability Board’s Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). The implicit assumption—that if risks are fully revealed, finance will respond rationally and in ways aligned with the public interest—is rooted in the “efficient market hypothesis” (EMH) applied to the finance sector and its perception of climate policy. For low carbon investment, particular hopes have been placed on the role of institutional investors, given the apparent matching of their assets and liabilities with the long timescales of climate change. We both explain theoretical frameworks (grounded in the “three domains”, namely satisficing, optimizing, and transforming) and use empirical evidence (from a survey of institutional investors), to show that the EMH is unsupported by either theory or evidence: it follows that transparency alone will be an inadequate response. To some extent, transparency can address behavioural biases (first domain characteristics), and improving pricing and market efficiency (second domain); however, the strategic (third domain) limitations of EMH are more serious. We argue that whilst transparency can help, on its own it is a very long way from an adequate response to the challenges of ‘aligning institutional climate finance’.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Achieving the Paris climate goals is a major long-term investment challenge, requiring vast and rapid investment into low-carbon and energy efficient technology, and the alignment of the financial sector with climate goals (Art 2.1c: COP21, CP.20/CP.20 2015; Boissinot et al. 2016; Jachnik et al. 2019). Meeting the current NDC pledges will require on average approximately US$130 billion per year investment in low-carbon technologies and energy efficiency (hereafter collectively referred to as “low-carbon”Footnote 1) between 2016 and 2030, an amount which could double or even treble for pathways consistent with the longer-term “well below 2°C” goal of the Paris Agreement (McCollum et al. 2018). Public finances alone are unlikely to mobilise these investments, so private finance at large scale is essential (UNFCCC 2018).

Particular hopes in this regard have been expressed for institutional investors, given their assets under management ($84 trillion in OECD countries in 2017, OECD 2018) and the long timescales of their liabilities, which potentially can match the timescales of climate change (Gründl et al. 2016; Nelson and Pierpont 2013; Kaminker and Stewart 2012; Della et al. 2011).Footnote 2 At present, however, less than 1% of global institutional investors’ holdings are in low-carbon assets (G20 2016), and they accounted for just 0.2% of total climate finance flows in 2016 (Buchner et al. 2017; Oliver et al. 2018).

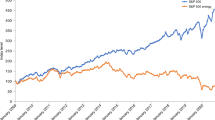

Indeed, institutional funds are far more invested in fossil fuel assets. Battiston et al. (2017) estimate that about 7% of insurance and pension funds’ equity portfolio are exposed to the fossil fuel industry, and that institutional investors’ broader exposure to climate-policy-relevant sectors (i.e. fossil-fuel, utilities, energy-intensive, housing, and transport) reach roughly 45% of their portfolio. This creates an additional concern about the ‘carbon bubble’ impact of a sudden transition on capital markets value and indirect impact on financial stability, first discussed by Mark Carney, the Governor of the Bank of England, in 2015 (Carney 2015; NGFS 2019). The contribution of Carney’s intervention was to argue that most financial actors were in fact ignoring climate change risks, for a mix of reasons including the lack of transparency as to exactly who was holding risky assets.

Following Carney’s speech, the Financial Stability Board—drawing analogies with the perceived causes of the 2008 financial crisis—argued that a large part of the problem arises from the lack of transparency around these asset holdings, and established the industry-based Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosure (TCFD). Fully implementing the resulting TCFD recommendations on disclosure to establish transparency across the financial system, is now a prime goal of industry and policy efforts in the climate finance arena (see chronology proposed by Chenet 2019b and recent literature on the nature and characteristics of climate-related financial risks, e.g. UNFCCC 2018; CISL 2018; Chenet et al. 2015; Gros et al. 2016; TCFD 2017).

The underlying assumption behind these initiatives is that exposing climate-related risks and opportunities to global scrutiny for all the main financial actors will cause investors (i) to move away from carbon-intensive assets to reduce risks and (ii) to move into low carbon opportunities to benefit from the enhanced market and value of low-carbon investments (Christophers 2017; Chenet 2019a).

The intellectual basis for believing that transparency can move large volumes of climate finance “from brown to green” resides in the assumption that markets will respond rationally to information—combining information from climate science and political declarations with concrete information (namely climate-related financial risks) on the holdings of climate-relevant assets, to change investment outlays. More specifically, it puts the onus on financial transparency, plus effective (“demand side”) climate policies, founded in commitments to the Paris goals and the most expected economic signal of carbon pricing.

Whether made explicit or not, this assumes something close to what is formally known as the ‘efficient markets hypothesis’ (Fama 1970). In assuming that adequate finance will flow given transparency and the right climate policy environment, it implicitly exempts the finance sector itself from the need for other regulatory actions beyond disclosure (Aglietta and Espagne 2016; Christophers 2017).

In this paper, we critically examine the move of institutional investment into low-carbon assets, but also consider the move out of carbon-intensive assets—i.e. the assumption that disclosure will drive an efficient market response to the “externality” of climate change. From a policy perspective, we thereby aim to establish overall whether the drive to transparency is likely to be a principal, or even major, contribution to aligning the finance sector with the low carbon transition.

To do so, we employ the Three Domains framework (Grubb et al. (2014) of economic decision-making, and use empirical evidence (from a survey of institutional investors), to probe some of the limits of the EMH. Our theoretical approach for exploring this builds on the Hall et al. (2017) utilisation of that framework, extending it in several ways as described in the next section, whilst our empirical evidence is provided by interviews with selected institutional investors, finance experts and academics, to reflect more fundamental characteristics of the finance sector and investors’ own perspectives. We bring these elements together to offer a broad analysis on the main drivers to spur mainstream investors out of high carbon assets, and into low-carbon investments. We thus advance the literature on institutional low-carbon investment by combining theory and empirics to probe a crucial policy-relevant question: to what extent can transparency reasonably be expected to align institutional finance to the low-carbon transition.

The paper is organised as follows. Section 2 presents the “Three Domains” of “Planetary Economics” as a framework to help organise relevant dimensions of economic decision theory (noting also its alignment with social science transition theories). This helps to integrate current literature on low-carbon investments and institutional investment barriers, together with the core structuring arguments of its application to finance in Hall et al. (2017), which to our knowledge remains the only such analysis. Section 3 describes our qualitative research methodology. Section 4 presents key results in terms of barriers to insurer and pension fund low-carbon investment, while section 5 reports policy solutions to boost institutional finance to the low-carbon transition. Section 6 is the conclusion.

2 Theoretical background and framework

Hall et al. (2017) observed that, at least prior to Paris Agreement and the subsequent TCFD efforts on disclosure, analysis of climate transformation has been “curiously quiet on the role of capital markets in financing energy transitions”, and suggest that this has been “due to a lack of suitable theory to supplant neoclassical notions of capital markets and innovation finance”. In other words, it has been broadly assumed that policy only needed to focus on the “demand-side” of the economy—on energy and related low carbon policy—and that finance would then flow accordingly.

The Hall et al. (2017) study critically analysed the development of renewable energy investment in the UK by employing the framework of the “three domains” of socio-economic processes developed by Grubb et al. (2014). In particular, they analyse the assumption that financial market follows the “efficient markets hypothesis” regarding low-carbon investments.

This framework identifies the presence of three complementary domains of economic processes and decision-making: satisficing, which reflects the insights of behavioural and organisation economics and is dominated by relatively short-term behaviour based on habits, routines, organisation and network constraints; optimising, which lies in neoclassical and welfare economic assumptions, dominated by economically rational actors that seek to maximise their utility within free and efficient markets; and transforming, which includes the insights of institutional and evolutionary economics to explore long-term processes of change, including strategic investment in new technologies, structures, infrastructure and institutions. These forces operate simultaneously across different time horizons and scale of actors (see Grubb et al. 2014 for further information).

The authors emphasise that the relative importance of the different domains will depend on the actors and issues in consideration, and argue that climate mitigation requires an unusual degree of emphasis across all three domains. To each domain is associated a different pillar of policy, reflecting the kind of interventions that could best affect the corresponding behaviour.

Studies taking the classical second domain perspective suggest that rational investors are driven by profit opportunities when selecting most attractive investments, and investors will provide the optimal level of financing at an equilibrium rate of return corresponding to level of risk (Fox 2011; Malkiel 2003). Financial actors will thus select and invest in low-carbon projects among other investment alternatives, once a profit opportunity in terms of returns and risk expectations is reached or created. There is a wide consensus in the literature that the lack of supportive policy frameworks, incentives and market-based instruments are the main barriers to attract private capitals for the low-carbon transition (Polzin 2017; Granoff et al. 2016; Fabian 2015; Jones 2015; Nelson and Pierpont 2013; Kaminker and Stewart 2012; Della Croce et al. 2011). Indeed, the appropriate investment policy framework and incentives are crucial in building confidence in investors’ expected returns and determining the investments’ profitability (Polzin et al. 2019). In addition, for insurers and pension funds, small project size can be a significant barrier as they do not invest directly in projects under about €100 million, due to cost due diligence (Nelson and Pierpont 2013; OECD 2016), while energy efficiency projects, for example, are typically €2 million to €10 million (Parker and Guthrie 2016). These form easily recognisable barriers, consistent with second domain EMH logic, and do not raise any deeper theoretical or policy issues.

Research on barriers to the low-carbon transition arising from financial behavioural (first domain) characteristics is increasingly prominent (Kahneman and Tversky 1979; Samuelson and Zeckhauser 1988; Shiller 2003, 2015; De Grauwe and Macchiarelli 2015). This points to ‘bounded rationality’ actors having diverse investment preferences, technology risk appetite, a priori beliefs, information and experience levels, influencing the actual level of low-carbon investments (Masini and Menichetti 2012, 2013; Lo 2004, 2012; Thomä and Chenet 2017). In particular, the lack of information and expertise in low-carbon assets are generally recognised as key reasons for the low level of investments in low-carbon assets by institutional investors (OECD 2015a; Nelson and Pierpont 2013; Kaminker and Stewart 2012; Della Croce et al. 2011), compounded by a lack of investment vehicles matching institutional investors’ preferences (Granoff et al. 2016; Nelson and Pierpont 2013; Kaminker and Stewart 2012). Additionally, Della Croce et al. (2011) found that investors have the general tendency to focus on recent past performance as a proxy for future performance (e.g. recency bias) that ultimately may lead to suboptimal investment decisions. For insurers and pension funds specifically, familiarity with the structure of investment transactions (e.g. investment type or partner managing the transaction), or with the local markets (Halland et al. 2018) may make them more likely to invest (Parker and Guthrie 2016).

Closer to third domain considerations, most recent studies emphasise the role of public policy and the lack of long-term goals and strategic investments by public authorities as key barriers to re-orienting capital towards low-carbon assets (Polzin et al. 2015; Mazzucato 2015; Nelson and Pierpont 2013; Kaminker and Stewart 2012; Della Croce et al. 2011). Mazzucato and Semieniuk (2018) empirically demonstrated how different types of financial agents support different subsets of technologies, creating technology directions (e.g. public actors supporting novel technologies). In a recent study, Geddes et al. (2018) showed that state investment banks are crucial not only to catalyse private investment but also to enable the financial sector creating trust for projects and taking a first mover role to help projects gain a track of record. These studies help to explain why in many countries, public finance—often through development banks, like the KfW in Germany—has been prominent in the funding of low-carbon investment; the role of institutional investors, in particular insurers and pension funds, is still very limited (Geddes et al. 2018; Mazzucato and Semieniuk 2018; Buchner et al. 2017).

Further studies of socio-technical transitions find that policy responses to structural features of economies or sectors, e.g. dominant investment risks and niche formation, influence low-carbon transitions (Unruh 2000; Foxon 2013). The “multi-level” perspective (MLP) pioneered by Geels (2002), summarised and applied to deep decarbonisation in Geels et al. (2017) considers indeed sociotechnical systems as a cluster of elements, involving technology, science, regulations, user practices, markets, cultural meaning, infrastructure, production and supply networks. Bolton and Foxon (2015) studying the UK energy sector find that investment risks in transitions are influenced by the structure of the economy as a whole. Whereas a centralised approach including nuclear power plants would lead to dominant construction risks for large projects, and in a decentralised approach market risks for smaller renewable energy projects would dominate, therefore policies to attract investments must be tailored accordingly.

To date, the only analysis to have explicitly applied the Three Domain framework to finance is the Hall et al. (2017) study of UK renewable energy investment. They emphasise that the efficient market hypothesis corresponds to purely second domain decision-making. Using data from the development of the UK renewables investment chain, they show that the need for capital market finance introduced a set of actors and behaviours incompatible with the EMH, including wide-ranging characteristics better described by (first domain) theories of behavioural finance (Shiller 2003, 2015), and clear inhibition of strategic decisions (third domain) on the long-term risks and opportunities of the low carbon transition. Specifically, they argue that in place of the EMH, the evidence clearly supports an alternative theory of adaptive markets (Lo 2012).

Our paper builds on Hall et al. (2017) in several ways. First by using the Three Domains framework to probe the highly policy-relevant question of the extent to which transparency could reasonably be expected to solve the perceived problems. Second, whereas Hall et al. (2017) take a vertical look at one sector in one country (UK), we conduct an international survey—semi-structured interviews with representative institutional investors from EU Member States and the USA, as well as experts from academia and the financial sector—and draw on a wider body of research on their behaviour. Third, our analysis disentangles explicitly the elements of policy framework, market factors, and organisational characteristics of institutional investors to better analyse the landscape in which they operate and more fundamental characteristics of the finance sector.

Consequently, this paper advances the debate on efforts to align the finance sector with the low carbon transition. We provide a wider understanding of the conditions under which new actions and policies have to be taken to ensure long-term sustainable investing, rather than rely entirely to transparency, as promoted in response to the TCFD recommendations.

3 Methodology

For the survey work, a two-stage expert elicitation process was undertaken. The first stage was an expert workshop with 25 institutional investors, policy-makers, civil society organisations and academics, held in London in July 2016 (see Supplementary materials for details). This workshop allowed for preliminary identification of key themes and factors relevant to institutional low-carbon investment. Insights from the workshop informed the second stage; semi-structured interviews with expert individuals (see Supplementary materials for interview protocol). Interviews were conducted with 11 North American and 21 European experts. The final interview sample included 8 pension funds, 10 insurers, 4 academics, 5 asset managers and 5 development finance institutions (DFIs). By investor type, assets under management (AUMs) of investors interviewed were as follows: insurers ($3495 billion), pension funds ($598 billion), asset managers ($5469 billion) and DFIs or other ($988 billion). Asset managers and DFIs were relevant for this study as they influence insurer and pension fund investment and could provide insight on their investment decisions; indeed they both deploy financial instruments (e.g. funds, green bonds) that insurers or pension funds invest in. We refer the interested reader to the Supplementary materials, which provide more detail on structural characteristics of investors in our sample, including AUM, and preferred investment instruments. These dimensions however do not make a core part of our analysis, as this goes beyond the scope of our study.

While this sample represents a range of actors relevant for understanding insurer and pension fund green investment strategies, we note that participants in our workshop and interviews are those with an orientation towards green investment. Thus, rather than being representative of mainstream institutional investing, our sample represents institutional investors with a green orientation. We argue that this nonetheless provides valuable insight into the challenges of financing the low-carbon transition because investors with an interest in green are likely to be the first-movers in such a transition, and thus analysing and overcoming the barriers that they face may be seen as a necessary first step towards achieving a low-carbon finance transition, with mainstream investors to follow once the transition is underway.

We then map the findings from this survey and the wider literature in a matrix. In addition to classification according to the domains of decision-making, we clarify where barriers arise from three main dimensions: (1) the climate policy framework, as distinct from (2) finance market structure, and (3) the capacities and governance structures of insurers and pension funds. The (1) group of barriers, in principle points to the classical role of climate policy, aiming to change the incentive structures arising between high and low carbon investment. The (2) and (3) groups reflect the financial system itself, respectively the impact of existing finance market structures, and the specific characteristics of institutional investors and their governance. Table 1 summarises the results of our enquiry and the rest of this paper details the analysis.

4 Results and discussions

4.1 Barriers arising from the policy framework

A key emerging storyline from the interviews was the perceived need for a clear and stable policy framework for low-carbon investment. Nearly every participant stated that the presence of such a framework is a key driver for low-carbon investment, and that a lack of it is a major barrier.

4.1.1 First domain

Participants stressed the importance of uncertainty surrounding future policy changes and related risks prediction as reason for their reluctance to invest in low-carbon assets. Indeed, as they have little insight into how policy may change in the future and how to manage it, they favour investments for which potential risks are perceived to be known, over unknown policy risks linked to low-carbon assets. Our interviews revealed investors’ tendency to avoid any explicit change in their portfolio allocation and investment choice until policy is very concrete. One participant stated that “given policy uncertainty, multiple trajectories/futures are possible as well as the risks that lie ahead - investors do not know which of such possible pathways is more likely to happen, and they would need to hedge their bets [referring to their investment choices] based on the current knowledge or they currently know”.

This phenomenon is known in the economic literature as the “ambiguity aversion”, which is the tendency to favour the known over the unknown, including known risks over unknown risks (Ellsberg 1961). Several studies documented that generally investors are ambiguity averse (Ahn et al. 2014; Bossaerts et al. 2010); however, ambiguity aversion has not been tested yet in low-carbon investment decision-making, suggesting the importance to account for such investors’ biases in low-carbon investment choice under uncertainty and future investment patterns.

4.1.2 Second domain

Clarity and transparency of policy instruments, and related rules and processes surrounding them, were recognised as crucial aspects. Two respondents stated that the specific instrument chosen for such a purpose does not matter, provided it is clear how the instrument generates suitable and stable returns, with transparency surrounding, for example, technology eligibility and permitting processes. Without this clarity, “such investments are a ‘no-go’”.

One respondent commented on the UK’s Contract for Difference (CfD) instrument for renewable electricity, stating that whilst the concept is simple and straightforward, the reality is much more complex, producing uncertainty on returns. Under this scheme, a generator party to a CfD is paid the difference between the “strike price”—a price for electricity reflecting the cost of investing in a particular low carbon technology—and the “reference price”—a measure of the UK average electricity market price (BEIS 2015). However, the strike price is set by auction, meaning the level of return for participants is unclear ex ante. The role of clarity and transparency also extends to the presence and operation of any review processes and adjustment mechanisms, and the terms of any contractual agreement and arbitration process. For instance, in the case of a “degression” mechanism under a feed-in tariff, the rates paid to new installations alters over time based on a pre-defined “trigger”, such as deployment rates in the previous quarter.

4.1.3 Third domain

Stability of policy instruments and mechanisms is another element mentioned. A key example continues to be support mechanisms for renewable energy. “An instrument such as a feed-in tariffs (FiT), which initially sets generous rates and thus produces substantial returns for investors, may be a ‘double-edged sword”. With generous rates, the cost of the instrument may rapidly increase as technology costs decline, and without pre-defined adjustment mechanisms, political pressure to abruptly introduce (perhaps extensive) changes rises. A number of participants raised this as a concern, with five explicitly citing the case of Spain, where between 2010 and 2013 retrospective cuts on remuneration for solar PV, wind and concentrated solar power (CSP) were introduced (EREF 2013). Abrupt changes (planned or actual) to support mechanisms in other countries in the past, including Italy and the UK, were also highlighted as barriers to previously planned or future investment.

Whether the jurisdiction in question holds credible long-term goals, strategies concerning low-carbon investments were also raised as a crucial aspect. Various participants stated that the presence (or absence) of such an overarching framework makes investment more (or less) attractive in a given jurisdiction. “Clarity of direction” and a “programmatic approach” are important. Investors do not want to enter into “one-off” deal, as this would require relatively substantial transaction costs (for direct investmentFootnote 3); instead, they seek to develop a viable long-term business in a given jurisdiction. Broadly, the more detailed such goals and strategies are, the more attractive the jurisdiction in question becomes (ceteris paribus). This also extends to clarity around the detail of how the achievement of such targets may be facilitated. A key example is the future design of electricity markets, which are commonly not designed to operate with a high proportion of renewable electricity. In the UK, for example, investors have “limited awareness of how the dynamics [regarding the design of electricity markets] will look over the next five years, let alone the next ten years”, potentially dampening investment.

Finally, the broader context of political climate and the rule of law in a given jurisdiction (e.g. whether abrupt changes are likely to be made to existing arrangements) determine the credibility of long-term goals and strategies. Participants drew a contrast, for example, between Germany and Italy. Where Germany is seen to provide a stable political climate, the Italian political landscape poses a risk to the attractiveness of low-carbon investment. Another example mentioned was the USA, where “climate policies and commitment have been compromised in the face of political stagnation”, and where investors “have the impression that the political landscape is very difficult”. The prospect of the election of Donald Trump to the US presidency was also raised, particularly in context of his stated plans to close the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (the interview sessions took place before the 2016 US election, between August and September 2016).

Another key storyline was the influence of public policies introduced for purposes other than encouraging low-carbon investment, such as the ‘unbundling’ requirement of the EU’s Third Energy Package (EU 2016a). “Unbundling” is the separation of energy supply and generation from the operation of transmission networks. The rationale behind such a requirement is that if a single company operates a transmission network, whilst also generating or selling energy, it may have an incentive to obstruct competitors’ access to infrastructure, preventing fair competition in the market. As such, no supply or production company (or investor) is allowed to hold a majority share or interfere in the work of a transmission system operator (in a given EU Member State) (EU 2016a).

Participants stated that being forced to choose between owning transmission or generation assets inhibits investment in low-carbon electricity generation. Faced with this choice, institutional investors might prefer transmission assets as being less risky—as they do not carry technology and price risks and indeed generally operate under direct regulation (e.g. rate-of-return) as monopoly assets (Nelson and Pierpont 2013).

4.2 Barriers arising from the finance market structures affecting the demand for low-carbon projects

Another storyline that emerged was the negative influence on low-carbon investment of finance market structure, including the lack of appropriate investment channels and tradable financial instruments, the small size of available projects and the paucity of data on potential low-carbon investments.

4.2.1 First domain

Participants cited the lack of tradable financial instrumentsFootnote 4 matching investors’ preferences as a key barrier. This is particularly relevant considering the preferences and portfolio allocations of insurers and pension funds, which remain heavily concentrated around liquid instruments, and which participants confirm would be the most promising channel for low-carbon investment if designed appropriately, despite the appeal of liquidity being acknowledged as an obstacle for long-term green investment (Demaria and Rigot 2018).

Many participants suggested that green bonds could be a promising liquid instrument to channel low-carbon investment, but they would need to be scaled up. At the present, green bonds are less tradable than regular bonds thus not satisfying investors’ liquidity needs. The California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS), challenged their potential, given their actual market liquidity in the secondary market, as they account for less than 1% of the total value of bonds outstanding.Footnote 5 The limited volume of green bonds traded (and therefore the actual low market liquidity) may impact investors’ ability to easily divest green bonds at limited price impact, as demand and supply for such securities might be mismatched.

Another factor mentioned is project size, which tends to be too small to attract institutional investment. Participants suggested that minimum investment values are required to make the transaction costs worthwhile (e.g. due diligence). The minimum value suggested is €50 million in Europe and $100 million in the USA, perhaps reflecting differences in size of investors from the respective regions of the world. Other researchers found that the minimum typical project size for an institutional investment is between $350 and $700 million (Nelson and Pierpont 2013; Vesy 2010).

The lack of high-quality data and standard reporting frameworks to allow appropriate due diligence and strategic planning process was cited as another key barrier to low-carbon investment. Examples of such data include expected GHG emission reductions, structure of the supply chain, carbon pricing implementation (e.g. scope and price level), exposure to other market (e.g. policy alterations) and climate (e.g. physical) risks. Although, several participants recognised growing efforts on climate risk disclosure, data related to CO2 intensity remain lacking. One participant stated that “the big challenge today is to link climate science and financial data, in particular integrating/computing impacts on companies’ assets into climate models”. Moreover, given the largely voluntary nature of GHG reporting (e.g. CDP reporting), participants have expressed concerns about the quality of reported data.

Moreover, these data lack reporting standards, producing reports of varied accuracy and coverage (Dupré et al. 2015). For instance, CalPERS declared that only 30% of the companies in which they are investing are disclosing basic carbon data, and even when these data are disclosed, there is no reporting standard format that provides a framework for climate change risk accounting. In our sample, only two participants are actively applying internal carbon prices and portfolio’s carbon footprint analyses. In particular, one participant stated that his organisation applies an internal carbon price of €35/tCO2 (rising €1 each year to €45/tCO2 in 2030) to screen fossil fuel power projects. Another participant reported that his organisation tries to assess its portfolio’s exposure to carbon risk by assuming the introduction of carbon taxes on direct GHG emissions (known as “scope 1”) of portfolio holding. This investor underlined that “the Greenhouse Gas Protocol—an international accounting tool for government and business to quantify and manage greenhouse gas emissions—is the first step to conceptualising the idea of emissions and prices on them, and it might become a very powerful tool”.

4.2.2 Second domain

One participant argued that actual institutional macro-investment trends in carbon-intensive assets result from investors’ rational thinking. He suggested that it may be perfectly economically rational for individual investors to ignore climate risks and continue to invest in carbon-intensive assets, if they judge and perceive that is how the market overall is behaving and will behave in the near future. Indeed, in the short term, divesting from carbon intensive assets would translate in a loss if the market continues to value them highly; hence, investors would simply follow market incentives. In the long term, eventually there will be a price correction—however, investors could be out of business before such market adjustments will materialise. In other words, individual investors would still perform well in the current market conditions, but their collective behaviour would lead the financial system towards more instability in the long term when climate risks will affect assets’ value. So, the outcome of individual rationality is collective irrationality.

This point reflects the view of some economists on how individual choices collectively can lead to economic turmoil. For instance, Rajan showed how rational responses, embedded in incentives to take on risks without balancing the dangers those risks pose, led to the last financial crisis (Rajan 2011). This analogy with the financial crisis driven by individual rational choices leading to collective irrationality has been inadequately investigated by studies on institutional finance for climate change. It suggests that beyond real barriers to investment, expectations of individual participants in the financial system on future possible low-carbon pathways and trajectories are likely to impact transition dynamics.

4.2.3 Third domain

Participants cited the lack of appropriate investment channels as a factor preventing more extensive low-carbon investment. Direct investment channels are relevant particularly for large institutional investors because of the associated costs of retaining internal expertise. Indeed, the high fixed costs of maintaining an internal dedicated team imply that the direct investment portfolio must be of a certain size and/or the investor has a strong interest in low-carbon assets. Nelson and Pierpont (2013) suggest that only 45 pension funds and 70–100 insurers worldwide could have the in-house expertise for direct investing in low-carbon projects. In our sample, only 2 participants declared direct investments in low-carbon projects. Smaller institutional investors tend to prefer indirect investment channels, transferring the selection and monitoring functions to a specialised manager. However, many participants expressed concern about the high fees they entail, indeed, several participants stated that investment funds and external managers usually demand a 2% management fee plus a 10–15% performance fee, reducing final returns.

Both direct and indirect investment strategies entail high transaction costs (e.g. investment appraisal and due diligence for direct investing, and high management and performance fees in indirect channels). Additionally, all the aforementioned barriers, namely ambiguity aversion, inadequate data and policy uncertainty, reinforce the need for more careful appraisal and due diligence resulting in higher transaction costs. Participants underlined the need for less ‘expensive’ investment channels to increase the involvement of institutional investors in low-carbon investment and the need to aggregate “small” projects into bigger investment products, funds and funds of funds, to make them at the relevant scale for investors. Previous research suggests that achieving a substantial increase in investment from institutional investors might be linked to the ability to develop internal capacity and expertise for direct low-carbon investment (Nelson and Pierpont 2013; Kaminker and Stewart 2012).

4.3 Barriers arising from insurers and pension funds’ organisational characteristics

A final storyline involves the organisational capacities of investors themselves, including the role of management experience and track record, their traditional investment in carbon-intensive assets and related investment time horizons.

4.3.1 First domain

Nearly all participants raised a lack of capacity, management experience and performance track record as one of the main factors limiting their low-carbon investments. The relative novelty of such investments and the lack of data and operational comparisons make it a challenging sector for investors. Even where they can see the benefits of low-carbon investment, they may not be able to accurately assess the risk profiles. One participant reported his attempt to co-invest with a first-time fund in energy efficiency in public schools. They bid together in a public auction, but they were disqualified given their lack of experience in the sector. A lack of investor capability and performance track record is also widely recognised in the literature as a limiting factor (Nelson and Pierpont 2013; Kaminker and Stewart 2012; Della Croce et al. 2011).

A key characteristic of ‘first domain’ behaviour is its short-termism, and this can be exacerbated by governance structures incentivising short-term performance, and related aspects of fiduciary duties. Insurers and pension funds are in theory long-term investors due to their liability structures (see Section 1). However, in practice, they often face short-term performance pressures and views that inhibit this characteristic (Bansal and DesJardine 2014). Several participants discussed the mismatch between the time-horizon of insurer and pension fund investment strategies and low-carbon assets. This mismatch can be explained by the principal–agent problem between constituents and insurer or pension fund, where one party acts on the behalf of the other. The constituent cannot be certain that the insurer or pension fund (agent) is acting in her interest, despite the importance of fiduciary duty in the mandates of funds manager. Moreover, when it comes to low-carbon assets, and more broadly to environment, social and governance (ESG) issues, the sensitive question is whether fiduciary duty should account for such extra-financial objectives in investment decisions. PRI (2015) has attempted to provide a final answer by suggesting the inclusion of ESG factors in fiduciary duty, quoting them “Failing to consider long-term investment value drivers—which include environmental, social and governance issues—in investment practice is a failure of fiduciary duty”. In the face of such challenge, regulators, including the European Commission, start to legislate on that issue to ensure sustainability considerations are integrated in the decision-making process (EC 2018a; HLEG 2018).

This uncertainty surrounding the genuine application of fiduciary duty by investment managers led their performance to being assessed frequently and short-term (usually annually or even quarterly) by pension funds from which they take their mandate; note that fiduciary duty should actually be demonstrated by pensions themselves towards their constituents (individual savers/pension holders).

Such monitoring incentivises the prioritisation of shorter- rather than longer-term returns, and it would not allow investors to factor climate risks into their investment decisions, as climate change is way beyond their investment timeframe.

Several studies on institutional investors more broadly have suggested that in practice they have an investment horizon ranging from less than 1 to 5 years, which is quite short compared with the potential materialisation of significant climate-related financial risks. Investment portfolios’ typical turnover of about 1–2 years (Bernhardt et al. 2017), and the horizon of financial analysis does not usually exceed 3–5 years (Dupré and Chenet 2012; Naqvi et al. 2017), while most asset managers’ incentives are based on an annual performance (Thomä et al. 2015). Moreover, at the employee level, portfolio managers are explicitly or implicitly benchmarked on much shorter-term performance, quarterly, monthly or even weekly (Naqvi et al. 2017). Christophers (2019) also reports that institutional investors are not worried about the implications of climate change, as they do not expect physical risks of climate change will be widely and substantially evident on most of the companies they are investing in today.

4.3.2 Second domain

Participants mentioned current insurance regulation, namely the “Solvency II” Directive (2008)/138/EC) as another factor influencing investment behaviour. The Directive seeks to provide a “harmonised, sound and robust prudential framework for insurance firms in the EU” (EU 2016b), meaning that insurers must assess the risks associated with their capital allocations and hold certain levels of liquid reserves to manage these risks. This incentivises investment in traditionally “safe” assets such as short-term government bonds, rather than long-term, less liquid and relatively more “risky” investments such as renewable electricity generation, against which they must hold higher levels of liquid reserves (ECF 2011). Several participants raised these requirements as a key barrier to low-carbon investment (and wider infrastructure) in the EU, and confirmed that Solvency II “penalises some of the investments [investors] would like to do in the renewable energy sector, as [the Directive] emphasises the importance of rating and…favours short-term investments”, with “[investments viewed] on a one-year horizon”. This is consistent with the reminiscing debate about the counter effect that Solvency II (and Basel III) could have on long-term/climate-friendly investments (D’Orazio and Popoyan 2019; Demaria and Rigot 2018; Chenet et al. 2017; Alexander et al. 2014; Spencer and Stevenson 2013).

4.3.3 Third domain

A few participants suggested that because institutional finance is still concentrated in carbon-intensive assets, it will likely continue to target these assets and not move to low-carbon investment. Scepticism about the seriousness of climate change has been indicated as a key factor. Whilst most of the investors covered in our survey were familiar with climate change issues, due to an intrinsic selection bias as we mainly interviewed managers in the sustainability/green units, general investors may only have peripheral and partial knowledge of or interest in the issue. For example, gained through channels such as Fox News or climate-sceptic think tanks in the USA which lead them to believe the problem is not that serious (this example was specifically mentioned by an American participant). Christophers (2019) indeed suggests that investors think about climate change subjectively—meaning imperfectly and individually—thus resulting in different ways of embedding climate risks in investment decisions.

Scepticism has also been mentioned regarding the prospects of strong government action. Many investors may regard the past 30 years since IPCC was launched Footnote 6 as evidence that governments are in fact unlikely to take serious action to mitigate CO2 emissions, citing for example the repeated failure of many carbon pricing systems (including all Federal-led efforts under the Obama Administration) and the non-binding nature of the Paris NDCs, which themselves are not aligned with the Paris Agreement “well below 2°C” target (Rogelj et al. 2016). Under the EMH view, markets would not able to reflect future market trends related to carbon-intensive assets into prices or accurately price high-carbon risk exposures, unless there are clear and credible signs that specific climate policies will be in place. In other words, the fact that there is no significant market move relative to carbon-intensive assets tends to prove that market participants actually do not believe climate policies are going to be implemented (at least within their respective time horizons) (Thomä and Chenet 2017).

It emerged also that investors’ over-confidence in new technology has led to the belief that carbon capture and storage and varied forms of ‘negative emissions’ will be the main lever to tackle climate change, and therefore high carbon investments can continue to be a mainstay of the economic system.

This belief has been reinforced by the use of the IEA’s scenarios as basis for the emerging scenario analysis incorporating financial markets, as promoted by the TCFD recommendations (2017). The financial community relies on such scenarios notably because they are global and multi-sector, and focus on investment needs. However, as such scenarios are technology driven to fit the forecasted demand, they support the overall confidence of the financial community that disruptive technology in the long term will be essential to ensure the low-carbon transition, compared with short term efforts, disruptive consumption patterns or changing priorities. Indeed, if one believes negative emission technologies will outperform in the long run, there is no ‘rationale’ to suffer for cutting emissions in the short term.

A final point raised is the belief that in case real ‘carbon bubble’ risks materialise, governments will have to bail out holders of fossil fuel assets to prevent collapse. Such investors’ perception is supported from the history of the financial crisis starting with the rescue of American International Group and the many banks and wider economic systems that received state help, from bailouts through to quantitative easing.

These findings suggest that investors’ expectations on future low-carbon pathways are shaping their current investment decisions and asset holding. Indeed, such expectations reflect both established investment and modes of economic thinking, which these tend to be based on static views of technologies, costs and risks. Analyses exploring the role of investors’ expectations with a focus on how these expectations will shape future low-carbon pathways are currently missing, but they seem to be crucial to re-orient institutional finance towards low-carbon projects. To the best of our knowledge, a few scholars have investigated numerically divestment from carbon-intensive assets induced by the introduction of new climate policies (Bauer et al. 2018; Schellnhuber et al. 2016; Johnson et al. 2015); however, none has tried yet to incorporate investors’ expectations on decarbonisation patterns into modelling projections.

5 Policies for overcoming barriers to insurer and pension fund low-carbon investment

Evidence from our interviews shows that the institutional low-carbon investment challenge encompasses several barriers and many interlinked factors operating simultaneously (e.g. “web of constraints”, Domenech et al. 2017) in all three domains of decision-making. Indeed, investors’ instrument preferences, their lack of information, experience and track record, and their ambiguity aversion (first domain), combined with weak incentives supporting low-carbon assets (second domain) and lack of appropriate investment channels and long-term climate goals not integrated into macro-economic and financial regulations as well as traditionally institutional investments in high carbon assets (third domain), have been identified as key factors hampering the scale up of institutional low-carbon finance.

We organise our discussion on actions needed and, in particular, on the role of transparency, to align the finance sector to the low-carbon transition around the 3 ‘pillars of policy’ reflecting the three domains of decision-making (Grubb et al. 2014). This section reflects the main findings in terms of policies discussed with interviewees—specifically we reported investors’ views on actions needed to mobilise institutional finance. Table 2 summarises the key policies identified.

5.1 First pillar of policy

The first pillar of policy seeks to address short-term behaviour based on habits, routines and organisational structures, which impede economically optimal responses, such as investors’ incentives for short-term decision horizons and lack of experience. Typical instruments include regulations/standards and various forms of engagement (e.g. information programmes) (Grubb et al. 2014).

The TFCD recommendations on disclosure are key actions needed to address such barriers as they would support and inform investors’ decision-making. Indeed, by increasing transparency on the exposure of assets or portfolios to transition risk, and more broadly on climate reporting, disclosure initiatives can help overcome the principal–agent problem between shareholders and insurers or pension funds, enabling insurers or pension funds to take a longer-term perspective.

Clear and reliable data—initially surrounding the carbon footprint of potential investments but more and more relative to the broader “climate alignment” (Chenet et al. 2017; Whitley et al. 2018; Jachnik et al. 2019)—is crucial to informing investors of their risk exposure from efforts to tackle CO2 emissions, e.g. through carbon pricing. Participants suggested a first step to promote the availability of such data would be to standardise methodologies for data collection and reporting, and link this to at least one of the two main financial reporting standards, i.e. the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) or the US Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (USA GAPP). Such standardisation would enable investors to request data regarding potential investments and facilitate disclosure initiatives. Policy requiring disclosure of relevant metrics would thus allow investors to manage climate policy risk themselves. The ISO standardisation organisation is currently building under future standard code 14097 its “Framework and principles for assessing and reporting investments and financing activities related to climate change” (ISO 2019a).

Disclosure may also produce competition between institutional investors, for instance, by reducing the carbon intensity of their investments. One participant stated that such competition appears to be occurring in France, following the entry into force of a mandatory climate change–related disclosure law on 1 January 2016 (Article 173), which requests French institutional investors to report on a number of items related to their strategy and risk management approach to climate change. Finally, reporting or disclosure policies interact with long-term strategic policies for a low-carbon transition. Participants discussed how disclosure may lead to mandatory targets for CO2 intensity of an investment portfolio, putting forward the example of legislation in California that prohibits public pension funds in the State (CalPERS and CalSTRS)Footnote 7 from making new investments or renewing existing investments in thermal coal companies after 1 July 2017 (Senate Bill No.185 was passed in October 2015). Since then, California Senate Bill SB-964 passed in 2018, requiring CalPERS and CalSTRS to report along similar lines than French Art.173 (CS 2018).

For green bonds in particular, actions to encourage the provision of accurate data (e.g. “greenness” of the financed activity, including data on which types of technologies/activities are financed and how those cope with the climate goals) alongside the provision of detailed information about what assets are included under the green bond label were perceived as highly relevant for increasing insurers and pension funds investment. Indeed, further standardisation of green bond definitions, structures and reporting would (i) provide more transparency and understanding of what green bonds are, allowing for appropriate assessment of risk/return profiles by investors; (ii) allow for the development of credible green bond labels and indices and (iii) allow the aggregation of several different bonds, enabling investment in a larger green bond portfolio by reducing transaction costs and spreading risk. In the policy space, we can note the current development of the ISO 14030 “Environmental performance evaluation” for “green debt” instruments (ISO 2019b), and the European Commission effort to develop a sustainable finance taxonomy, defining the economic activities consistent with the European long-term sustainable strategy (EC 2018a; 2018b).

Additionally, other policies addressing first domain barriers, but not linked to disclosure, were suggested by our participants. In particular, the scale up of liquid financial instruments matching insurers and pension funds’ expectations and targeting large low-carbon projects was perceived as highly relevant. Most participants suggested that green bonds are the most promising liquid instrument to channel low-carbon investment, representing a niche to be scaled up to attract more investment. Indeed, green bonds could be perceived as an appropriate way of “piggybacking” low-carbon assets into the existing bond market structure familiar to investors. Moreover, participants underlined the need to target large low-carbon projects to allow insurers and pension funds to reduce due diligence costs and invest at scale. Nevertheless, while green bonds are certainly the most prominent financial instrument promoted by financial institutions and governments themselves (EC 2018a), it is important to mention that green bonds are not unanimously seen as the perfect tool. Indeed, they rely on multiple subjective definitions of greenness, which opens many doors for greenwashing (S&P DJI and Trucost 2016; Langner 2016; Global Capital 2016), and their real green additionality and added value is still to be demonstrated (I4CE 2016; WWF 2016). This is particularly relevant as it appears that markets unfold many non-labelled climate-aligned bonds genuinely labelled green bonds (CBI 2018; Dupré et al. 2018).

These findings reinforce evidence suggested in the literature on institutional investors more generally and policy action on transparency. The lack of information and expertise in low-carbon assets are generally recognised as one of the main reasons for underinvestment in low-carbon assets, and actions to provide more reliable data and more broadly on disclosure are needed (Nelson and Pierpont 2013; Kaminker and Stewart 2012; Della Croce et al. 2011). Moreover, as suggested by other scholars, attracting institutional investors will require a further development of green bonds and other liquid financial instruments matching investors’ preferences (Granoff et al. 2016; Nelson and Pierpont 2013; Kaminker and Stewart 2012).

Quite surprisingly, none of the participants mentioned actions to reform investors’ governance structure to avoid short-term performance and time horizons discrepancy, although this was mentioned as a relevant barrier to long-term sustainable investing. In this regard, organisational reforms revising both managers’ incentives schemes along with the way the climate risks are assessed would be critical to solve the time horizon discrepancy. For instance, linking executive compensation to meet climate-aligned corporate goals would allow managers to set expectations for a strategy consistent with the 2 °C target. Since remuneration structures are used to help deliver on the companies’ objectives, this must be the starting point of engagement. On the other hand, treating risks from climate change like other financial risks, rather than viewing them simply as a corporate social responsibility issue, would keep away from assets that do not satisfy financial risk standards, where risk is assessed using more comprehensive methodologies that include climate-related criteria (Campiglio et al. 2018). This seems to be happening in the UK banking system, where a recent report from the Bank of England suggests that oversight of the financial risks from climate change and overall responsibility for setting the strategy, targets and risk appetite relating to these risks is beginning to be considered at board level (BoE 2018).

At policy level, the European High-Level Expert Group on Sustainable Finance (HLEG 2018) and the subsequent European Commission action plan actually devoted significant attention to “attenuating short-termism in capital markets” (EC 2018a). More specifically, the EC is looking at whether portfolio turnover and equity holding periods by asset managers are unduly short-term oriented, and whether potential capital markets practices generate undue short-term pressure in the real economy. At corporate governance level, the EC is inquiring the possible need to clarify the rules according to which directors are expected to act in the company’s long-term interest. Whilst being limited to studies without any clear action in the policy agenda, having these issues mentioned by regulators, it is a clear sign of their relevance and the policy attention devoted to them.

5.2 Second pillar of policy

Policies to address barriers in the second domain mainly focus on markets and pricing. They intend to internalise the environmental externalities of energy production and consumption, to correct market failures, influence the market structure and related terms of investments. For this kind of barriers, disclosure initiatives would only help indirectly market responsiveness. As by improving transparency on finance alignment to climate goals, investors would increase their awareness on their portfolios’ exposure and climate risks and would consequently better react to market and policy signals.

A key element is the introduction of policy instruments that explicitly seek to incentivise low-carbon investment and meet the needs of insurers and pension funds. As one participant noted, such instruments must adhere to “the three ‘L’s—Long, Loud and Legal”. In the context of renewable electricity support instruments, for example, they must convey confidence to the investor that they will be in place for long enough for a return on the investment to be generated, they must target assets of a sufficient magnitude to attract institutional investors, and they must have a sufficient legal foundation to provide confidence that terms of an agreement or contract will not (or cannot) be changed once in place. To this end, governments could, for example, ensure that such instruments are sustainable in the long-run and designed in such a way that adjustments in the face of uncertainty (e.g. rapidly decreasing technology costs) are possible, according to pre-defined and well publicised rules (e.g. degression mechanisms).

Participants broadly encouraged instruments and actions that would alter the balance of value and risk between low-carbon investments and their high-carbon equivalents, to make the former the more competitive option. This may be through action to reduce the cost of low-carbon technologies and services and to increase the cost of high-carbon alternatives. This would reduce (or remove) the need for the instruments and actions discussed above and the potential uncertainty they entail. Several participants confirmed that the most appropriate action to achieve this goal would be to introduce “stable and meaningful carbon pricing”. Despite carbon pricing being “the elephant in the room that nobody talks about”, participants state that “it would be extremely helpful to introduce a carbon price…as it would create opportunities”, and although “it is an unpopular political measure…it is the true answer to the question”. Some participants even stated that carbon pricing is “essential” and “the only way to lead the low carbon transition”, although one participant stated that carbon pricing is not the only way, it would likely be “the best and most encompassing’.

Finally, changes in the financial regulatory system not targeted at low-carbon goals have been raised (e.g. reform of the Solvency II Directive) as crucial to facilitating low-carbon investment. One participant stated that adjustments “that reduce liquid capital allocation could be a really significant driver [for low-carbon investment]”. This could be done, as another participant suggested, by including other investment vehicles under the “qualifying infrastructure investments” category. Another participant stated that such a change could have a much greater impact on low-carbon investments by EU insurers than adjustments to energy policy in multiple EU Member States. More generally, it emerged that the importance of the introduction of new and reform of existing elements of the broader policy and regulatory framework to facilitate low-carbon investment.

The crucial role of supporting policies and carbon pricing to drive low-carbon investment is widely recognised in the literature (Polzin 2017; Nemet et al. 2017; Nelson and Pierpont 2013; Wood et al. 2013; Kaminker and Stewart 2012; Della Croce et al. 2011). Previous research has also underlined the effect of policy credibility on investment, indeed when regulatory rules are not believable then investors become short-sighted and unable to make socially optimal investments (Bosetti and Victor 2011; Polzin et al. 2019). Many researchers suggest that a mix of market-based instruments, including carbon prices, direct support mechanisms such as feed-in tariffs, capacity-based measures such as quotas and tradable green certificates, and fiscal measures such as tax incentives and rebates, is crucial to support low-carbon investment (Metcalf 2009; Fischer and Newell 2008; Haas et al. 2004; Hanson and John 2004).

5.3 Third pillar of policy

Policies in the third domain promote technical and institutional innovation, along with infrastructure and cultural changes, that can deliver the scale and quality of investment needed to meet the Paris goals. For such strategic transformations, disclosure initiatives seem inadequate and an excessive reliance upon them may even risk displacing other measures required to align the finance sector with climate goals.

Most of participants called for public leadership—through institutions such as state investment banks—to play a key “market shaping” role through its early, risk-taking and patient direct investments rather than only through indirect public incentives supporting private investments (Ryan-Collins 2019; Mazzucato and Semieniuk 2018). Indeed, participants recognised that institutional investors will not be the first movers towards the low-carbon transition, but eventually they will follow strong public directions and signals. They instead would change their investment behaviour in response to a mixture of long-term policy signals, patient capital and greater involvement of the DFIs in key strategic phases of the investment channel.

Our interviews identified substantial processes of government-backed low-carbon investments, where public entities act as investors. Strategic public investments, which look beyond short-term returns and influence investors’ expectations, may be made through two key channels. The first is through the use of Green Public Procurement (GPP) to provide a substantial market for low-carbon assets, which may in turn stimulate the private market. GPP includes the use of power purchase agreements (PPAs) for low-carbon electricity, and energy efficiency requirements for public buildings. Aggregating energy efficiency investments in public buildings may provide a substantial investment opportunity, with one participant viewing this as less risky than private sector energy efficiency projects, as the public sector provides guarantees.

The second channel is through development finance institutions (DFI). Several participants stated that DFIs have an “extremely important role to play…in encouraging inflow of more private capital in the [low-carbon] sector”. Indeed, DFIs are able to favourably alter an investment’s risk/return profile through the provision of “belts and braces” in order to attract institutional investment. For example, DFIs could increase the use of dedicated de-risking instruments, such as “first-loss” guarantees, which would compensate for a given proportion for a first tranche of potential losses, up to a threshold value of the investment or portfolio as a whole. DFIs may also conduct the appropriate due diligence for investments. If such a burden is taken on by DFIs, it is reduced for co-investors, reducing transaction costs. Participants stated that institutional investors tend to trust the quality of due diligence undertaken by DFIs. Another potential action is the pooling of investment opportunities, allowing institutional investors to invest at scale with a diversity of underlying assets and reduced transaction costs. One participant with direct experience of investment pooling stated that once a DFI proposed pooling investments, potential investors “were all much more comfortable”.

Our participants mainly linked the transition to a low-carbon economy to long-term public investments, whilst not mentioning policy interventions that could be promoted by other institutions, such as Central Banks or financial regulators. Recently, several scholars underlined the importance of unconventional monetary policies, such as quantitative easing targeting the purchase of green assets to enable a greater involvement of the private sector (Campiglio et al. 2018; Monasterolo and Raberto 2018). Other scholars stressed the importance of reforms from the banking system, for instance by easing lending conditions for low-carbon investments and relaxing macro-prudential regulation, such as green differentiated reserve and specific capital requirements in favour of low carbon assets, to leverage more funds towards such assets (Campiglio et al. 2018; Campiglio 2016; Volz 2017).

Finally, whilst few participants mentioned the “unbundling” requirement of the EU’s Third Energy Package as limiting their low-carbon investments, they did not propose any specific action on this aspect. During the interviews, it emerged that investors are careful of the legal risks surrounding their investment decisions and will generally avoid sectors with this level of uncertainty, reaffirming the general importance of uncertainty as key factor for investment decision and the need to consider investors’ perspective when designing harmonised energy policies.

These findings underline doubts about the idea that transparency will be sufficient to move large-scale finance out of “brown”. Promoting greater insurer and pension fund low-carbon investment would require simultaneous policies accounting for behavioural practices, pricing frameworks and market design, structural barriers and not only disclosure initiatives as promoted in the TCFD recommendations. More transparency would likely address barriers linked to investors’ inexperience and lack of clear and reliable data to inform their decision-making. Transparency might also be relevant to better assess climate-related issues and their potential financial implications, thus preventing potential “carbon bubble” risks and avoiding a repeat of a financial system crashing under the revelation (and re-evaluation) of worthless assets. It is this, perhaps more than anything else, that disclosure is supposed to address. The hope is that fear of carbon bubble risks would drive institutional investors to move money out of these assets and into clean energy investments that would insulate them from this risk. However, transparency will not likely impact the barriers in the other domains, especially the long-term thinking and strategic investment decision (third domain).

Put together with all our findings about the specific barriers to institutional investment in low-carbon transformation, our interviews suggest that even for those investors who do for varied reasons move assets out of fossil fuels might choose many other options in preference to strategic investments in long-lived, low carbon and innovative green assets.

6 Conclusion

This paper provides a wider understanding of the conditions under which new actions and policies have to be taken to ensure long-term sustainable investing, rather than rely entirely to transparency, as assumed in the EMH and promoted in response to the TCFD recommendations. We both explain theoretical frameworks (grounded in the “three domains”), and present empirical evidence (from a workshop and in-depth interviews with 32 low-carbon and institutional finance experts), to probe some of the limits of the EMH.

We found that attracting greater insurer and pension fund low-carbon investment requires simultaneous policy actions accounting for behavioural practices (first domain), pricing frameworks and finance market design (second domain) and structural barriers (third domain). Policies focusing on the development of standards and engagement, and more generally on disclosure, such as data collection and reporting standards, may enable investors to overcome incentives for short-term decision-making. Moreover, the scale up of liquid financial instruments targeting large low-carbon projects will further increase insurers and pension funds’ involvement in the low-carbon economy. Finally, reforms revising both managers’ remuneration schemes along with the way climate risks are assessed would be critical to avoid short-term performance and time horizons discrepancy. Policies based on markets and pricing instruments would influence the profitability of low-carbon investments and increase their attractiveness to insurers and pension funds. Further, reforms of policies that act upon institutional investors for purposes other than encouraging and facilitating low-carbon investment, e.g. Solvency II, are also needed. Policies promoting technical and institutional innovation, along with cultural changes, can create the conditions for institutional strategic long-term investment. In particular, strategic deployment of public long-term capital in key phases of the investment channel, such as development finance institutions deploying de-risking instruments and pooling projects together, together with long-term policy signals, might allow institutional investors to invest at scale. Along these lines, policy interventions promoted by central banks or financial regulators, including for instance unconventional monetary policies, such as quantitative easing targeting the purchase of green assets or easing lending conditions for low-carbon investments and relaxing macro prudential regulation would be beneficial. Finally, less expensive investment channels and reforms of the anti-monopoly regulation in the EU will also help to increase low-carbon investments.

Our study thus addressed a gap in the literature exploring insurers and pension funds perspective on long-term strategic investment and the main drivers to spur mainstream investors out of high carbon assets and into clean investments. We assess in particular the potential importance of disclosure, given its widely recognition in the TCFD recommendations and the latest policy initiatives designed also at European level aiming at increasing awareness of and transparency in the financial system (e.g. EU taxonomy of green sectors and assets, EU 2019). We argue that whilst transparency can help, on its own, it is a very long way from an adequate response to the challenges of “aligning climate finance”.

Promising areas of future research include analysing investors’ investment choices and interactions in the financial system, to understand the mechanisms by which changes in investors’ expectations, dynamics and other institutional evolutionary processes can be triggered. For instance, in our analysis, it emerged clearly that expectations of individual participants in the financial system on future possible low-carbon pathways are likely to impact investment decisions and transition dynamics. Therefore, understanding investors’ expectations on the speed and shape of decarbonisation patterns and how these affect investment decisions could be a crucial area for future research.

Moreover, recent studies suggest that the co-evolution of investors’ perceptions and structural change create capital markets for given assets (Hall et al. 2017). Indeed, the heterogeneity and dynamism of investor preferences for financial assets in an evolving technological, regulatory and economic environment, determine the actual low-carbon investment landscape and the speed of overall low-carbon transition (Lo 2004, 2012; Polzin et al. 2017). Future efforts should be also devoted to a deeper understanding of the interactions between the different domains and corresponding pillars of policy to implement actions that ultimately can transform the climate finance landscape.

Notes

In the paper, we define “low-carbon investments” as those that reduce the emissions of greenhouse gases, compared with a counterfactual in which the investment is not made, based on the common understanding of the investor community we interviewed. Particular examples of low-carbon investments we explored are those in renewable electricity production projects and transmission infrastructure, and investments in energy efficiency in buildings and in industrial production processes.

The fact that institutional investors have long-term liabilities does not seem to translate automatically into long-term investment practices. Several studies revealed the ‘artificial shortening of their time horizons’ as in practice, investors and financial intermediaries operate on much shorter time horizons (Naqvi et al. 2017; Thomä et al. 2015; Chenet 2019a). Moreover, it is important to note that institutional investors could potentially invest a limited part of their AUM in infrastructure assets - where low-carbon investment would fit - due to recent regulations (Solvency II and Basel III, please see further discussion in the next sections).

Direct investments are equity ownership or debt instruments (e.g. bonds, loans) at company or project level, managed by the investor itself. For indirect investment channels, investors rely on specialist intermediaries (e.g. investment and infrastructure funds, external managers) to select and manage investments.

Tradable (and liquid) financial instruments are assets that can be easily and quickly converted into cash with minimal impact to the price received.

The IPCC was created in 1988.

CalPERS and CalSTRS, respectively California Public Employees’ Retirement Fund and Teachers’ Retirement Fund

References

Aglietta, M. and Espagne, E. (2016) Climate and finance systemic risks: more than an analogy? The climate fragility hypothesis, CEPII Working paper

Ahn D, Choi S, Gale D, Kariv S (2014) Estimating ambiguity aversion in a portfolio choice experiment. Quant Econ 5(2):195–223

Alexander, K., T. Strahm, A. Balmer, A. Voysey, C. Abb (2014). Stability and sustainability in banking reform: are environmental risks missing in Basel III? UNEP Working paper

Bank of England (2018) Transition in thinking: the impact of climate change on the UK banking sector. Bank of England, Prudential Regulation Authority

Bansal P, DesJardine MR (2014) Business sustainability: it is about time. Strateg Organ 12:70–78

Battiston S, Mandel A, Monasterolo I, Schütze F, Visentin G, G. (2017) A climate stress-test of the financial system. Nat Clim Chang 2017(7):283–288

Bauer N, McGlade C, Hilaire J, Ekins P (2018) Divestment prevails over the green paradox when anticipating strong future climate policies. Nat Clim Chang 8:130

BEIS (2015). Electricity market reform: contracts for difference, [Online] Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/electricity-market-reform-contracts-for-difference

Bernhardt, A., R. Dell, J. Ambachtsheer, R. Pollice, S. Dupre, M. Naqvi, B. Burke, D. Saltzman (2017). The long and winding road: how long-only equity managers turn over their portfolios every 1.7 years. Mercer, 2° Investing Initiative, The Generation Foundation

BNEF, (2013). New investment in clean energy fell 11% in 2012. BNEF note

Boissinot J, Huber D, Lame G (2016) Finance and climate: the transition to a low carbon and climate resilient economy from a financial sector perspective . OECD working paper. OECD Publishing, Paris

Bolton R, Foxon TJ (2015) A socio-technical perspective on low carbon investment challenges – insights for UK energy policy. Environ Innov Soc Trans 14:165–181

Bosetti V, Victor DG (2011) Politics and economics of second-best regulation of greenhouse gases: the importance of regulatory credibility. Energy J 32:1–24

Bossaerts P, Ghirardato P, Guarnaschelli S, Zame W (2010) Ambiguity in asset markets: theory and experiment. Rev Financ Stud 23:1325–1359

Buchner, B.K., P. Oliver, X. Wang, C. Carswell, C. Meattle, F. Mazza. (2017) Global landscape of climate finance 2017, Climate Policy Initiative

Campiglio E (2016) Beyond carbon pricing: the role of banking and monetary policy in financing the transition to a low-carbon economy. Ecol Econ 121:220–230

Campiglio E, Dafermos Y, Monnin P, Ryan-Collins J, Schotten G, Tanaka M (2018) Climate change challenges for central banks and financial regulators. Nat Clim Chang 8(6):462

Carney M (2015) Breaking the tragedy of the horizon - climate change and financial stability. In: Speech by Mr Mark Carney, governor of the Bank of England and chairman of the Financial Stability Board, at Lloyd’s of London, London, 29 September 2015. Bank of England, London

CBI (2018). Bonds and climate change — the state of the market 2018. Climate Bonds Initiative

CBI (2019). Green bonds - the size of the market 2018. Climate Bonds Initiative report

Chenet, H. (2019a). Planetary health and the global financial system. Rockefeller Foundation Economic Council on Planetary Health working paper