Abstract

Parent stress and mental health problems negatively impact early child development. This study aimed to systematically review and meta-analyze the effect of eHealth interventions on parent stress and mental health outcomes, and identify family- and program-level factors that may moderate treatment effects. A search of PsycINFO, Medline, CINAHL, Cochrane and Embase databases was conducted from their inception dates to July 2020. English-language controlled and open trials were included if they reported: (a) administration of an eHealth intervention, and (b) stress or mental health outcomes such as self-report or clinical diagnosis of anxiety and depression, among (c) parents of children who were aged 1–5 years old. Non-human studies, case reports, reviews, editorials, letters, dissertations, and books were excluded. Risk of bias was assessed using the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Study Quality Assessment Tools. Random-effects meta-analyses of standardized mean differences (SMD) were conducted and meta-regressions tested potential moderators. 38 studies were included (N = 4360 parents), from 13 countries (47.4% USA). Meta-analyses indicated eHealth interventions were associated with better self-reported mental health among parents (overall SMD = .368, 95% CI 0.228, 0.509), regardless of study design (k = 30 controlled, k = 8 pre-post) and across most outcomes (k = 17 anxiety, k = 19 depression, k = 12 parenting stress), with small to medium effect sizes. No significant family- or program-level moderators emerged. Despite different types and targets, eHealth interventions offer a promising and accessible option to promote mental health among parents of young children. Further research is needed on moderators and the long-term outcomes of eHealth interventions. Prospero Registration: CRD42020190719.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Families have faced unprecedented challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our recent family health research of 3000 Canadian families (Cameron et al., 2020) found that more than 50% of mothers are experiencing clinically significant psychosocial distress, including depression (48%), anxiety (67%), and relationship problems (19%). Pandemic stressors are exacerbating domestic conflict (Arenas-Arroyo et al., 2021), parenting requirements such as loss of regular childcare (Neece et al., 2020; Patrick et al., 2020), financial problems (Cameron et al., 2020; Gassman-Pines et al., 2020), and loneliness (Killgore et al., 2020; Li & Wang, 2020). These pandemic-related impacts are of particular concern given that children exposed to adversities such as maternal mental illness, cumulative stress, and unsupportive parenting are at-risk for health and developmental impairments. For example, exposure to maternal depression in the first 5 years of life is linked to alterations in physiological regulation, cognitive impairments, and mental illness, with up to 60% of exposed children developing psychological disorders during their life course (Rahman et al., 2013; Rasic et al., 2014). Cumulative parenting stress (e.g., life stress, daily hassles) when children are 3 to 5 years old is associated with poor child functioning (e.g., negativity, behavioural problems) at 5 years of age as well as negative parent–child relationship quality (e.g., less positive affect, more conflict) (Crnic et al., 2005).

Innovative programs are needed to manage stress and treat widespread mental health problems among parents and buffer children from serious stressors of the COVID-19 pandemic. Interventions to promote parent mental health capacities during the first 5 years of a child’s life are expected to yield high health and economic benefits (Doyle et al., 2009), and optimize the chances that children become healthy and productive members of society (Campbell et al., 2014). For example, an individual participant data meta-analysis of 14 randomized trials indicated that the Incredible Years parenting programme for families with children aged 2–10 years old is associated with significant improvement in child behavior and reduced health and social service utilization (e.g., hospital/doctor visits, psychological and social work services, educational resources) costs (Frances et al., 2017). Early interventions can also prevent the long-term consequences of parent mental illness from becoming imbedded in children’s biological and behavioral development (Bernard-Bonnin et al., 2004). Moreover, in a three-year patient-oriented research-priority setting initiative (Bright et al., 2018), parents of young children (from conception to age 2) identified their top priority as support for families to develop healthy coping and emotion regulation (Brockway et al., 2021). Families also wanted access to evidence-based information, tailored to their needs, delivered in timely formats (Brockway et al., 2021).

With limited access to in-person services during the pandemic due to the restrictions and measures put in place to limit the spread of COVID-19, there is an unprecedented need for accessible delivery of programs for parents. eHealth is an emerging field focused on delivery of health services and information through or enhanced by Web-based programs, remote monitoring, teleconsultation, and mobile device-supported care (World Health Organization, 2011). eHealth can also help overcome barriers to in-person mental health care faced by families such as stigma, long waitlists and provider unavailability, financial and logistical issues with transportation, childcare and missed work, limited insurance coverage for private services, limited access to evidenced-based treatments in rural areas, and preferences by mothers for accessing in-home mental health services (Dennis & Chung-Lee, 2006; Flynn et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2010; Osborn et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2019). Parents face many challenges with managing their own health, relationships, and careers while balancing taking care of their children’s health, promoting their social and emotional development, and overseeing their education. Engagement in, and success of, treatment may be hindered by parents believing that they should not experience distress, by thinking their children’s needs should be tended to before their own, or due to fear of being judged as a bad parent or fear of losing custody of their children (Abrams et al., 2009; Anderson et al., 2006). General mental health services may not be as effective because the unique stressors and beliefs about parenthood are not adequately addressed.

Evidence-based eHealth programs have been developed for the prevention (Deady et al., 2017) and treatment (Păsărelu et al., 2017) of depression and anxiety, often with large to medium effect sizes. However, the use of eHealth is a relatively new area in family care. To date there have been only a few eHealth-related meta-analyses, including four looking at online or technology-assisted parenting programs (Florean et al., 2020; Harris et al., 2020; Spencer et al., 2020; Thongseiratch et al., 2020) and one of telehealth family therapy programs (McLean et al., 2021), all with parent mental health as secondary outcomes. Some recent meta-analyses have also examined eHealth interventions for postpartum mental health (Feng et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2020), which represents a distinct period with unique challenges and care provisions where treatment needs and content would differ from that after infancy. However, there have been no systematic reviews or meta-analyses of the literature that identifies the effectiveness of a broader range of eHealth programs on mental health among parents of young children, specifically. There is thus a clear need to synthesize the findings to date on the potential for eHealth interventions to promote mental health among parents of young children, as well as improve our understanding of the factors that influence treatment response.

The present study is a systematic review and meta-analysis of available data on eHealth interventions and mental health outcomes of parents with young children (1–5 years of age). The objectives of the current study were to: (1) meta-analyze the effect of eHealth interventions on parent stress and mental health such as anxiety and depression symptoms, and (2) identify family- and program-level factors that may moderate the magnitude of treatment effects. Potential moderators for consideration included family-level demographics (such as child age) and baseline severity (of child and parent symptomatology), as well as program-level characteristics (such as intervention target, comparison, delivery, modality, retention and engagement) and study quality.

Methods

This investigation follows the methods outlined by the Cochrane Collaboration’s Handbook (Higgins et al., 2011) and the standards set by Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) (Moher et al., 2015; Page et al., 2020). The protocol for this study was registered with Prospero (CRD42020190719) through the University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (MacKinnon et al., 2020).

Eligibility Criteria

The methods for this review follow the Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome (PICO) framework (Schardt et al., 2007). The population of interest was parents (adults over 18 years of age) who are the biological or primary caregivers of young children (mean or 25% of sample aged 1 to 5 years, 11 months old). The current review included studies that evaluated eHealth interventions and parent mental health outcomes. eHealth interventions could be administered to parents alone or with their children, with or without referral, targeting a wide range of content including parent mental health, parenting skills, and child behaviour. Programs that comprised additional components utilizing technology (e.g., texting, video-conferencing) were included, whereas non-adapted programs that were simply delivered via telehealth (e.g., manualized CBT over the phone) were excluded in order to provide a more robust evaluation of interventions designed for eHealth, which would help inform further program development. In terms of comparators, both controlled (e.g., randomized controlled trials or those with comparison groups, such as active conditions, waitlists, treatment as usual or standard care) and pre-post (e.g., open trials) design studies were included given this is a relatively new field. The outcome of interest was parent mental health, such as anxiety, depression, and/or stress; studies were included that assessed level of symptomatology (as measured on validated self-report scales) or change in clinical diagnosis (using either the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric, 2013) or the International Classification of Diseases (World Health Organization, 1993) Mental and Behavioural Disorders criteria and determined using a diagnostic interview or assessment and/or information available from medical record review).

Secondary outcomes of interest (not required for inclusion) related to feasibility and acceptability of eHealth interventions for parents included engagement (e.g., number or percent of video/session/homework completion), retention (e.g., < 20% missing data or drop-outs), and participant satisfaction (e.g., subjective reports).

Search Strategy

Relevant literature was identified through a comprehensive search of five electronic databases including Cochrane, Embase, Medline and PsycINFO via OVID, and CINAHL via EBSCOhost, from inception to July 2020. In addition, we hand searched the references of reviews and meta-analyses from the database search, and checked whether data from protocols, posters and dissertations from the database search had been subsequently published. Search criteria was constructed collaboratively with a research librarian with expertise in the area of psychology. The search terms included database specific controlled vocabulary, field codes, operators, relevant keywords, and subject headings to identify the participant population (parents), the exposure (eHealth interventions), and the outcome (mental health). A broad list of search terms to capture parental stress and mental health problems were included (see Supplementary Material for the full list). Studies were restricted to those published in English.

Study Selection

After all relevant articles were identified and duplicates removed using Covidence Systemic Review software (Veritas Health Innovation, http://www.covidence.org), two reviewers (KP and KS) independently screened the titles and abstracts to determine eligibility for inclusion in the full-text review, and a third reviewer (ALM) supervised and reviewed 100 records to ensure > 85% consistency. Peer-reviewed studies that reported original data on eHealth intervention outcomes for parents of young children (mean or 25% of sample within 1–5 years, 11 months old) including anxiety, depressed mood, and/or stress were retained for full-text review, while non-human studies, case reports, reviews, editorials, letters, dissertations, and books were excluded. The two reviewers subsequently conducted a full-text review to determine eligibility for inclusion in the systematic review and meta-analysis, and discrepancies were resolved by consensus with the third reviewer. Where multiple studies using data from the same larger study met inclusion criteria, consensus was used to determine which would be included, based on having the largest and least restricted sample and/or most recent publication date. Study investigators were contacted by email to confirm population criteria (i.e., children’s age) if not reported.

Data Extraction

The following data were extracted: general study information (e.g., year, country, design, comparison group, sample size), participant demographics (e.g., age, race/ethnicity, gender/sex, income, education), description of the eHealth intervention (e.g., target, delivery method, duration), methodology (e.g., recruitment, randomization, comparison, statistical analysis), mental health outcomes (e.g., type of distress, measurement tool, means and standard deviations of scores), as well as any available feasibility and acceptability information (e.g., engagement, retention, satisfaction). Data extraction was conducted independently by the two reviewers (KP and KS) and discrepancies were resolved by consensus with the third reviewer (ALM). Study investigators were contacted by email to obtain outcome data (e.g., means and standard deviations for measures of mental health) if not reported.

Quality Assessment

Study quality was assessed using the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Study Quality Assessment Tools for Controlled Intervention Studies and for Before-After (Pre-Post) Studies with No Control Group (NIH, 2020), which include 14 and 12 items, respectively, to evaluate studies for potential flaws in reported methods or implementation, including sources of bias such as selection, performance, attrition and detection, as well as confounding and power. The last item of the pre-post tool, regarding interventions conducted at group level, was removed as it was not applicable to any of the included studies. Study quality was assessed independently by the two reviewers (KP and KS), and discrepancies were resolved through consensus with the third reviewer (ALM). Total scores were converted to percentages (Maass et al., 2015) for ease of comparability and sensitivity analyses. Scores of 50.0% or above on the NIH Quality Assessment Tools indicate good quality (Maass et al., 2015). The NIH tools are commonly used and recommended (Ma et al., 2020).

Data Analysis

All analyses were conducted with the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA; Version 3.0) software (Borenstein et al., 2019). Random-effects models were used to be conservative due to presumed heterogeneity across studies (due to differences in sample, interventions, and outcome measures), using the DerSimonian and Laird estimator (DerSimonian & Laird, 1986). A combined mean treatment effect was computed for studies with multiple comparisons and/or outcomes (Borenstein, 2009) and standardized mean differences (SMD) were compared across studies to account for the use of different measurement tools (Egger et al., 2008). The overall meta-analysis used the inverse variance method to compute a pooled SMD point estimate and a Hedge’s g effect size, with 95% confidence intervals (CI), for eHealth interventions across all included studies (using composite scales over subscales where available). A positive SMD estimate indicates that those in the eHealth intervention group had a greater decrease in symptoms than those in the comparison group in controlled studies, or that symptoms significantly decreased after receiving the eHealth intervention in pre-post studies. SMD and Hedge’s g of 0.20, 0.50, and 0.80 can be interpreted as small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively (Cohen, 1988; Faraone, 2008). Stratified meta-analyses were also conducted by study type (controlled, pre-post) and outcome (anxiety, depression, general stress, parenting stress, trauma). Meta-regression with random effects models were conducted when there were enough studies (k = 3) that included a moderator of interest, those without data were excluded. Potential moderators included: family-level demographics (child age, parent ethnicity, education, income, and partnered status) and baseline severity (of child and parent mental health symptomatology), as well as program-level characteristics (intervention target, comparison group, delivery, modality, retention and engagement) and study quality.

Heterogeneity was assessed using Cochrane’s Q test, which evaluates variance between studies, and the I2 index, which evaluates the proportion of heterogeneity between studies (Higgins & Thompson, 2002). Potential publication bias was assessed through visual inspection of funnel plots as well as Begg and Mazumdar’s rank correlation and Egger’s regression intercept tests. A sensitivity analysis was conducted to determine the impact of each study on the meta-estimate by sequentially removing one study at a time. Methodologically flawed studies were retained if the analysis indicated they did not significantly affect the meta-estimate (Paulson & Bazemore, 2010; Stroup et al., 2000).

Results

Literature Search

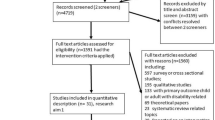

As outlined in Fig. 1, the database search resulted in 8128 records and hand searching resulted in 40 records, for a total of 8168 imported into Covidence. Following removal of 3202 duplicates, the abstracts of 4966 articles were screened. The full-text of 225 articles were reviewed for eligibility (with 29 discrepancies resolved by the third reviewer, the proportion of agreement was 87%). Investigators of 13 studies were contacted to clarify the parent population (i.e., children’s age), of which 7 were excluded for not meeting criteria (Bragadóttir, 2008; Kaplan et al., 2014; Kuhlthau et al., 2019; Love et al., 2016; Phipps et al., 2020; Sairanen et al., 2020) or not responding (Moghimi et al., 2018), while 6 were included (Book et al., 2020; James Riegler et al., 2020; Jones et al., 2017; Nicholson et al., 2009; Sheeber et al., 2017; Whitney & Smith, 2015). A total of 37 articles met inclusion criteria, with one comprising two separate studies (David et al., 2017), therefore 38 studies (testing 34 unique interventions) were included.

Study Characteristics

Characteristics for each of the 38 eligible studies are reported in Table 1. Studies were published between 2000 and 2020, with samples ranging from 5 to 464 individual parents, from 13 countries, where the majority (k = 18) came from the United States. The total sample included in the meta-analysis was N = 4360, with 34 studies having samples composed of 51% or more mothers. Of the 38 studies included, eight comprised pre-post designs and 30 controlled designs, including 27 randomized and three non-randomized trials. Among the controlled studies, 19 used a non-specific comparison (e.g., waitlist, standard care, treatment as usual) not intended to be therapeutic, 9 used a specific active comparison (e.g., booklet or non-eHealth version of intervention, education or health promotion) intended to be an active condition (Wampold, 2015), and 2 used both. In terms of program delivery and modality, 23 of the eHealth interventions were classified as fully digital (3 App-based, 20 Web-based; e.g., online modules), 9 were clinician led (e.g., phone, video-conferencing, etc.), and 6 included both digital components and clinician contact. 22 interventions targeted parent mental health or stress (in general or related to having children with medical conditions) and 16 targeted parenting skills or children’s behaviour problems. In terms of recruitment, 10 studies were open (e.g., online ads & posters), 16 used specific settings (e.g., clinics, hospitals, schools), 4 allowed both program/clinical referral (e.g., Head Start Centers) and open recruitment (e.g., self-referral, ads), 3 were follow-up studies, and 5 did not report.

In the 32 studies that reported children’s age, the means ranged from 1.6 to 6.6 years old, and in the 31 studies that reported parents’ age, the means ranged from 24.4 to 41.0 years old. Of the 23 studies that reported on race or ethnicity, 18 studies had samples where more than half of the participants were of European descent. Of the 29 studies that reported education, seven samples were classified as disadvantaged following the procedure used by Penner-Goeke et al. (2020): i.e., mean or > 15% of sample without high school completion (American average in 2016-2017 school year; McFarland et al., 2019). 12 studies had samples that were classified as income disadvantaged following the procedure used by Penner-Goeke et al. (2020): i.e., mean or > 10.5% (American poverty rate in 2019) (Semega et al., 2020) of the sample below the American poverty level ($21,720) for a family of three in 2020 (Amadeo, 2021), or if income data were not collected a subjective determination was based on other information (e.g., employment status, sampling methods, representativeness). Of the 27 studies that reported marital status, the proportion of partnered (e.g., married, in a relationship) parents ranged from 27.8 to 100%. Of the 16 studies that reported child baseline data, eight studies had mean child behaviour problems above a clinical cut-off. Of the 32 studies that reported parent baseline data, 12 studies had mean parent mental health problems above a clinical cut-off level.

As for mental health outcomes, the majority of studies either reported symptoms of depression (k = 19) or anxiety (k = 17). 12 studies reported parenting stress, 10 reported general stress, and 4 reported on symptoms of trauma. 5 studies only reported composite scores (e.g., combined scores of anxiety, depression and stress). All of the included studies used self-report questionnaires, only one reported using a scale that had not been validated yet (Skranes et al., 2015). The full breakdown of outcome measures by study is available in the Supplementary Materials. The investigator of one study was contacted to obtain outcome data (Patton et al., 2020).

Quality Assessment

The majority of studies (71.1%) scored 50.0% or above on the NIH Quality Assessment Tools (see last column in Table 1), indicating good quality and overall low risk of bias (Maass et al., 2015). Selection bias was low, as 90.0% of the controlled studies were described as randomized, 73.3% used adequate sequence generation, but only 26.7% reported allocation concealment, while all of the pre-post studies had prespecified eligibility criteria and were deemed to comprise representative samples. There is a low risk of confounding, as 73.3% of the controlled studies reported no differences between groups at baseline. There is some risk of performance bias as only three of the controlled studies reported blinding of participants and providers, likely due to the behavioral nature of the interventions (versus pharmacological), and only three reported that other interventions were avoided or were similar for both groups. However, 56.7% of controlled studies were deemed to have high adherence (based on author statements or reports indicating > 50% completion such as session attendance, module completion, video access) and all of the pre-post studies reported the intervention was delivered consistently. There is potential risk of detection bias as only six of the included studies reported blinding of outcome assessors, however all but one reported using validated self-report measures. In terms of attrition bias, 55.3% of included studies reported < 20% drop-outs and 60.5% reported accounting for missing data in their analyses.

eHealth Treatment Effects on Parent Mental Health

Findings from the meta-analyses, as outlined in Fig. 2, indicated that overall eHealth interventions are associated with significant improvement in mental health symptomatology among parents (SMD = 0.368, SE = 0.072, 95% CI: 0.228, 0.509, p < 0.001; Hedges’s g = 0.362, SE = 0.071, 95% CI: 0.224, 0.501, p < 0.001). Significant heterogeneity was observed among studies (Q = 175.09, p < 0.001, I2 = 78.87). The Egger’s regression intercept was non-significant (b = − 0.596, t = 0.916, p = 0.366), however Begg and Mazumdar rank correlation was significant (Kendall’s tau = 0.228, χ2 = 161, p = 0.044), and the funnel plot (Fig. 3) indicated slight asymmetry, which suggests some evidence of publication bias among studies.

Stratified meta-analyses indicated that eHealth interventions are associated with improved mental health symptoms regardless of whether the study had a control group or not (SMDcontrolled = 0.339, SE = 0.093, 95% CI: 0.157, 0.521, p < 0.001, Hedge’s g = 0.334, SE = 0.092, 95% CI: 0.154, 0.514, p < 0.001; SMDpre-post = 0.463, SE = 0.124, 95% CI: 0.221, 0.706, p < 0.001, Hedge’s g = 0.450, SE = 0.119, 95% CI: 0.217, 0.683, p < 0.001), and across most of outcomes measured including anxiety (SMDanxiety = 0.533, SE = 0.140, 95% CI: 0.259, 0.807, p < 0.001, Hedge’s g = 0.525, SE = 0.138, 95% CI: 0.254, 0.796, p < 0.001), depression (SMDdepression = 0.379, SE = 0.106, 95% CI: 0.170, 0.587, p < 0.001, Hedge’s g = 0.372, SE = 0.104, 95% CI: 0.168, 0.576, p < 0.001), and parenting stress (SMDparenting stress = 0.341, SE = 0.147, 95% CI: 0.052, 0.630, p = 0.021, Hedge’s g = 0.330, SE = 0.142, 95% CI: 0.051, 0.609, p = 0.020), but not general stress (SMDstress = 0.274, SE = 0.359, 95% CI: − 0.430, 0.978, p = 0.446, Hedge’s g = 0.271, SE = 0.355, 95% CI: − 0.426, 0.967, p = 0.446) or trauma (SMDtrauma = 0.461, SE = 0.311, 95% CI: − 0.148, 1.070, p = 0.138, Hedge’s g = 0.447, SE = 0.303, 95% CI: − 0.147, 1.042, p = 0.140).

Sensitivity Analyses

After systematically removing one study at a time, it was observed that four studies affected the meta-estimate of the effect size of parenting eHealth interventions by more than 5% (David et al., 2017; Fidika et al., 2015; Hemdi & Daley, 2017; Sourander et al., 2016). One study (David et al., 2017) affected the meta-estimate such that it made the estimate less conservative, although a significant association was still noted without the study included (p < 0.001). Three studies affected the meta-estimate such that they made the estimate more conservative; a significant association was still noted without the studies included (p < 0.001). Upon evaluation of study quality, two of the studies (David et al., 2017; Sourander et al., 2016) were deemed to be moderate quality (rated as 6 and 7 out of 14) and two studies were evaluated to be of high quality with one study being rated as 12 of 14 (Hemdi & Daley, 2017), and the other study being rated as 9 of 11 (Fidika et al., 2015). As such, all of the identified studies were included in the analyses.

Moderators of eHealth Treatment Effects

Results of the meta-regression indicated no statistically significant differences in the eHealth interventions’ treatment effect by family- or program-level factors (see Table 2). However, higher study quality was associated with larger effect sizes.

Feasibility and Acceptability

In terms of feasibility, 22 studies reported on measures of engagement (e.g., session attendance, module completion, video access), of which there were 12 studies where the majority of the sample completed at least 75% of the intervention, and 18 where the majority completed at least 50%. Regarding retention, 21 studies reported a drop out rate of 20% or less. In addition, 16 studies reported on measures of acceptability (e.g., satisfaction, found helpful, would recommend), of which there were 13 studies where 75% of the sample or “high levels” indicated acceptability, and all had 50% or “high levels” of acceptability.

Discussion

The current systematic review and meta-analysis synthesized the literature on the effectiveness of eHealth interventions for promoting mental health among parents of young children. Meta-analyses of the 38 included studies indicated that eHealth interventions are associated with improved parental mental health, with small to medium effect sizes observed across trial designs (controlled or pre-post) and outcomes measured (symptoms of anxiety, depression, and parenting stress). No significant family- or program-level moderators of eHealth intervention effectiveness for parent mental health were identified. Results also suggested good feasibility and acceptability of eHealth interventions for parents of young children, with the majority of included studies reporting high levels of engagement, retention, and satisfaction among participants. These findings highlight the potential value of eHealth interventions for addressing unmet parent mental health needs, which may be particularly widespread during and following the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our findings demonstrate slightly higher effectiveness for improving parent mental health than other meta-analyses of online parenting and telehealth family therapy interventions, which reported small to moderate effect sizes, with Hedge’s g ranging from − 0.29 to − 0.31 (McLean et al., 2021; Spencer et al., 2020; Thongseiratch et al., 2020). Prior meta-analyses focused exclusively on parenting or family health interventions with children ranging from 0 to over 18 years old, whereas the current investigation included a broad range of programs and focused on mental health outcomes among parents of young children. Similarly, meta-analyses of eHealth interventions for general mental health indicate small to moderate effects for depression (Massoudi et al., 2019). A recent meta review of meta-analyses specifically examining mobile apps for mental health in the general population also revealed small to medium effects (Lecomte et al., 2020). Finally, the pooled eHealth intervention effect we observed for parent mental health is comparable to the small to medium effect sizes reported in meta-analyses for in-person psychological interventions targeting parenting stress and maternal depression, which fall within the Hedge’s g range of 0.30 to 0.64 (Burgdorf et al., 2019; Cuijpers et al., 2015). Therefore, eHealth interventions represent an accessible alternative that yield effect sizes that are comparable to traditional face-to-face psychotherapy for parent mental health.

The stratified meta-analyses results indicated a medium effect of eHealth interventions for parent mental health in pre-post studies, whereas controlled studies had a small effect. It is possible that treatment effects were obscured by symptom changes in the comparison groups. Indeed, small effects are often observed in waitlist groups (Steinert et al., 2017), perhaps due to participating in a mental health study and/or expectancies about eventually receiving treatment. Interestingly, moderation analyses in the current investigation indicated no statistically significant difference in eHealth treatment effects between studies that used active (e.g., in-person, education) vs. waitlist or usual care comparison groups.

We also found a medium effect of eHealth interventions for symptoms of anxiety, and small to moderate effects for symptoms of depression and parenting stress. Anxiety symptoms may be particularly responsive to eHealth intervention, whereas parents experiencing depression may struggle with motivation to engage in these forms of treatment with less clinical contact or guidance. This highlights the expected importance of incorporating behavioral activation in eHealth interventions. Results of the stratified analyses also indicated the effect of eHealth interventions on general stress and trauma symptomatology were not statistically significant, potentially due to the relatively small number of studies that measured these outcomes (k = 8 and k = 3, respectively). Additionally, a cursory review of the general stress measures used suggests that they may be capturing multiple layers of stress related to chronic stress, uncertainty or uncontrollable situations (e.g., job insecurity, structural inequities), which would not be proximal targets of parenting or parent mental health interventions. It is also possible that programs targeting parenting-related stress and mental health problems are not easily generalized to other non-parenting stressors.

The identification of family-level moderators can help to streamline the referral process by prioritizing for or matching programs to those who will benefit most from eHealth interventions. Similarly, identifying program-level moderators helps to highlight the barriers and components of the treatment process that are important for success, and thus can inform and improve the future development and delivery of eHealth interventions. Interestingly, none of the potential moderators tested in the current investigation were found to significantly modify the eHealth treatment effect. This finding is consistent with other recent meta-analyses of online parenting programs in which results did not differ by children’s baseline behavior or emotional problems severity, delivery method, or type of comparison condition (Thongseiratch et al., 2020), nor by children’s mean age, parents’ education, session completion, or dropout rate (Florean et al., 2020). It may be that these family- and program-level factors are not as relevant for the unique challenges faced by parents of young children compared to those for general adult mental health services (i.e., eHealth in and of itself addresses some of the barriers parents face), or for eHealth interventions compared to in-person treatment. Although previous research indicated that guided web-based interventions are more effective in general (Heber et al., 2017), it has been suggested that therapeutic alliance is not as important for online intervention effectiveness as it is for face-to-face psychotherapy, and that practical or supportive guidance may be sufficient for online interventions (Andersson & Titov, 2014). One recent meta-analysis found no differences in outcomes of online parenting programs with and without access to clinical support (Spencer et al., 2020), while another demonstrated that interventions involving direct contact were more effective for parents experiencing social disadvantage (Harris et al., 2020). It is possible that certain program-level factors only moderate eHealth treatment effects for certain family-level factors, thus necessitating a further analysis of their interplay. In the current investigation, only study quality emerged as a significant moderator, such that higher quality ratings were associated with higher eHealth treatment effect size.

The non-significance of target (parent mental health or stress versus parenting skills or children’s behaviour problems) as a moderator indicates that even eHealth interventions specifically designed to treat children’s needs and/or improve parenting skills have a secondary benefit of promoting the mental health of parents. This finding is consistent with previous meta-analyses of online parenting programs showing small to moderate effect sizes for parental stress and depression (Spencer et al., 2020; Thongseiratch et al., 2020). Future research is warranted to examine the potential underlying pathways, including whether reducing child behavioral and emotional problems may lead to less parental distress and/or whether increases in positive parenting skills and self-efficacy to manage children’s problems may reduce parental distress.

Preventing exposure to parental stress and mental health problems is critical during the first 5 years of children’s lives, as it impacts their developmental outcomes. The findings of this meta-analysis have important implications for practice and policy. As part of a stepped care model that could improve the efficiency of health care systems, family care providers should consider recommending eHealth interventions to parents experiencing low to moderate stress or mental health problems as a first line treatment option, given its effectiveness, accessibility and lower resource use. Response to eHealth interventions should be monitored and more intensive services (e.g., in-person therapy, psychiatry referral) recommended as necessary.

Strengths and Limitations

This systematic review and meta-analysis represents the largest and most comprehensive synthesis of the literature to date, as it included a broad range of eHealth interventions and mental health outcomes. We employed a thorough search strategy developed with a librarian (ZP) who has expertise in this area. Nevertheless, the results of the current investigation should be interpreted within the context of several limitations. Although the included studies utilized different designs and measured different mental health outcomes, the results were consistent and remained significant across the stratified meta-analyses. There was also a wide variety of types of eHealth interventions including apps, video-conferencing, and website-based programs, as well as differences in level of contact with clinicians, which could have contributed to heterogeneity of treatment effects. However, whether the eHealth programs were fully digital or included some clinician contact was not found to be a significant moderator of treatment effectiveness. As the number of studies on eHealth programs for parents increases, future meta-analyses could further examine differences in modalities and use of technology. The current meta-analyses included pre and post-intervention, but not follow-up, data, so we cannot draw conclusions on the long-term effectiveness of eHealth programs for parent mental health. It is also important to note that the results are limited to mental health symptomatology, as almost all of the included studies used validated self-report questionnaires. Future meta-analyses with studies reporting on clinical diagnosis and remission rates (which requires contact) would provide a fuller picture of the potential impact of eHealth interventions on parent mental health. Given the majority of studies that reported on race/ethnicity had samples with more than half of participants from European descent (18/23), and that 15 studies did not provide this information, the findings from the current meta-analysis may not be generalizable to Black, Indigenous, and people-of-color (BIPOC) groups. Similarly, the current review only included parents who were 18 years of age or older. Thus, the results may not apply to parents who are teenagers, who often have unique circumstances and treatment program needs (Jamison & Feistman, 2021). There was also some indication of publication bias, such that there is a lack of small studies with small or statistically insignificant effects. This bias may have been more pronounced with the inclusion of gray literature (e.g., abstracts from conference proceedings, dissertations). However, a recent study suggested that including grey literature has minimal impact on the results of reviews (Hartling et al., 2017). Lastly, one potentially eligible study was excluded (Moghimi et al., 2018) from the current investigation as the authors could not be contacted to determine the age range of participants’ children, and thus it is unknown if and how it would influence the pooled effect size.

Conclusion

Given the importance and influence of parents during the first 5 years of life for child development, eHealth interventions offer a promising and accessible option to promote mental health among parents of young children, particularly for symptoms of anxiety and depression as well as parenting stress.

Data Availability

Available upon request from corresponding author.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Abrams, L. S., Dornig, K., & Curran, L. (2009). Barriers to service use for postpartum depression symptoms among low-income ethnic minority mothers in the United States. Qualitative Health Research, 19(4), 535–551. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732309332794

Amadeo, K. (2021). Federal Poverty Level Guidelines and Chart. The Balance. https://www.thebalance.com/federal-poverty-level-definition-guidelines-chart-3305843

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association.

Anderson, C. M., Robins, C. S., Greeno, C. G., Cahalane, H., Copeland, V. C., & Andrews, R. M. (2006). Why lower income mothers do not engage with the formal mental health care system: Perceived barriers to care. Qualitative Health Research, 16(7), 926–943. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732306289224

Andersson, G., & Titov, N. (2014). Advantages and limitations of Internet-based interventions for common mental disorders. World Psychiatry, 13(1), 4–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20083

Arenas-Arroyo, E., Fernandez-Kranz, D., & Nollenberger, N. (2021). Intimate partner violence under forced cohabitation and economic stress: Evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Public Economics, 194, 104350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104350

Baker, M., Biringen, Z., Meyer-Parsons, B., & Schneider, A. (2015). Emotional attachment and emotional availability tele-intervention for adoptive families. Infant Mental Health Journal, 36(2), 179–192. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21498

Bernard-Bonnin, A.-C., & Psychosocial Paediatrics Committee, Canadian Paediatric Society. (2004). Maternal depression and child development. Paediatrics & Child Health, 9(8), 575–598. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/9.8.575

Book, F., Goedeke, J., Poplawski, A., & Muensterer, O. J. (2020). Access to an online video enhances the consent process, increases knowledge, and decreases anxiety of caregivers with children scheduled for inguinal hernia repair: A randomized controlled study. Journal of Pediatric Surgery, 55(1), 18–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2019.09.047

Borenstein, M. (2009). Introduction to meta-analysis. Chichester: Wiley.

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L., Higgins, J., & Rothstein, H. (2019). Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software, Version 3.

Boyle, R. J., Umasunthar, T., Smith, J. G., Hanna, H., Procktor, A., Phillips, K., Pinto, C., Gore, C., Cox, H. E., Warner, J. O., Vickers, B., & Hodes, M. (2017). A brief psychological intervention for mothers of children with food allergy can change risk perception and reduce anxiety: Outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. Clinical and Experimental Allergy, 47(10), 1309–1317. https://doi.org/10.1111/cea.12981

Bragadóttir, H. (2008). Computer-Mediated Support Group Intervention for Parents. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 40(1), 32–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2007.00203.x

Breitenstein, S. M., Fogg, L., Ocampo, E. V., Acosta, D. I., & Gross, D. (2016). Parent use and efficacy of a self-administered, tablet-based parent training intervention: A randomized controlled trial. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 4(2), e36.

Bright, K. S., Ginn, C., Keys, E. M., Brockway, M. L., Tomfohr-Madsen, L., Doane, S., & Benzies, K. (2018). Study protocol: Determining research priorities of young albertan families (The Family Research Agenda Initiative Setting Project—FRAISE)—Participatory Action Research. Frontiers in Public Health, 6, 228. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00228

Brockway, M. L., Keys, E., Bright, K. S., Ginn, C., Conlon, L., Doane, S., Wilson, J., Tomfohr-Madsen, L., & Benzies, K. (2021). Top 10 (plus 1) research priorities for expectant families and those with children to age 24 months in Alberta, Canada: Results from the Family Research Agenda Initiative Setting (FRAISE) priority setting partnership project. British Medical Journal Open, 11(12), e047919. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047919

Burgdorf, V., Szabó, M., & Abbott, M. J. (2019). The Effect of Mindfulness interventions for parents on parenting stress and youth psychological outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1336–1336. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01336

Cameron, E. E., Joyce, K. M., Delaquis, C. P., Reynolds, K., Protudjer, J. L. P., & Roos, L. E. (2020). Maternal psychological distress & mental health service use during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Affective Disorders, 276, 765–774. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.081

Campbell, F., Conti, G., Heckman, J. J., Moon, S. H., Pinto, R., Pungello, E., & Pan, Y. (2014). Early childhood investments substantially boost adult health. Science, 343(6178), 1478–1485.

Cernvall, M., Carlbring, P., Ljungman, L., Ljungman, G., & von Essen, L. (2015). Internet-based guided self-help for parents of children on cancer treatment: A randomized controlled trial: Internet-based guided self-help for parents. Psycho-Oncology (chichester, England), 24(9), 1152–1158. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3788

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Crnic, K. A., Gaze, C., & Hoffman, C. (2005). Cumulative parenting stress across the preschool period: Relations to maternal parenting and child behaviour at age 5. Infant and Child Development, 14(2), 117–132. https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.384

Cuijpers, P., Weitz, E. S., Karyotaki, E., Garber, J., & Andersson, G. (2015). The Effects of Psychological treatment of maternal depression on children and parental functioning: A meta-analysis. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 24(2), 237–245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-014-0660-6

David, O. A., Capris, D., & Jarda, A. (2017). Online coaching of emotion-regulation strategies for parents: Efficacy of the online rational positive parenting program and attention bias modification procedures. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 500–500. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00500

Deady, M., Choi, I., Calvo, R. A., Glozier, N., Christensen, H., & Harvey, S. B. (2017). eHealth interventions for the prevention of depression and anxiety in the general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 310–310. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1473-1

Dennis, C.-L., & Chung-Lee, L. (2006). Postpartum depression help-seeking barriers and maternal treatment preferences: A qualitative systematic review. Birth, 33(4), 323–331.

DerSimonian, R., & Laird, N. (1986). Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Controlled Clinical Trials, 7(3), 177–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2

Doyle, O., Harmon, C. P., Heckman, J. J., & Tremblay, R. E. (2009). Investing in early human development: Timing and economic efficiency. Economics & Human Biology, 7(1), 1–6.

Egger, M., Smith, G., & Altman, D. (2008). Systematic reviews in health care: Meta-analysis in context (2nd ed.). Wiley.

Ehrensaft, M. K., Knous-Westfall, H. M., & Alonso, T. L. (2016). Web-based prevention of parenting difficulties in young, urban mothers enrolled in post-secondary education. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 37(6), 527–542. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-016-0448-1

Faraone, S. V. (2008). Interpreting estimates of treatment effects: Implications for managed care. Pharmacy and Therapeutics, 33(12), 700.

Farris, J. R., Bert, S. S. C., Nicholson, J. S., Glass, K., & Borkowski, J. G. (2013). Effective intervention programming: Improving maternal adjustment through parent education. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 40(3), 211–223. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-011-0397-1

Feng, Y. Y., Korale-Liyanage, S., Jarde, A., & McDonald, S. D. (2021). Psychological or educational eHealth interventions on depression, anxiety or stress following preterm birth: A systematic review. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 39(2), 140–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2020.1750576

Fidika, A., Herle, M., Lehmann, C., Weiss, C., Knaevelsrud, C., & Goldbeck, L. (2015). A web-based psychological support program for caregivers of children with cystic fibrosis: A pilot study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 13(1), 11.

Florean, I. S., Dobrean, A., Păsărelu, C. R., Georgescu, R. D., & Milea, I. (2020). The efficacy of internet-based parenting programs for children and adolescents with behavior problems: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 23(4), 510–528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-020-00326-0

Flynn, H. A., Henshaw, E., O’Mahen, H., & Forman, J. (2010). Patient perspectives on improving the depression referral processes in obstetrics settings: A qualitative study. General Hospital Psychiatry, 32(1), 9–16.

Fortier, M. A., Bunzli, E., Walthall, J., Olshansky, E., Saadat, H., Santistevan, R., Mayes, L., & Kain, Z. N. (2015). Web-Based Tailored Intervention for Preparation of Parents and Children for Outpatient Surgery (WebTIPS): Formative evaluation and randomized controlled trial. Anesthesia and Analgesia, 120(4), 915–922. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000000632

Frances, G., Patty, L., Joanna, M., Sabine, L., Victoria, H., Jennifer, B., Eva-Maria, B., Judy, H., & Stephen, S. (2017). Could scale-up of parenting programmes improve child disruptive behaviour and reduce social inequalities? Using individual participant data meta-analysis to establish for whom programmes are effective and cost-effective. Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3310/phr05100

Franke, N., Keown, L. J., & Sanders, M. R. (2020). An RCT of an online parenting program for parents of preschool-aged children with ADHD symptoms. Journal of Attention Disorders, 24(12), 1716–1726. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054716667598

Gassman-Pines, A., Ananat, E. O., & Fitz-Henley, N. J. (2020). COVID-19 and parent-child psychological well-being. Pediatrics, 146(4), e2020007294. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-007294

Harris, M., Andrews, K., Gonzalez, A., Prime, H., & Atkinson, L. (2020). Technology-assisted parenting interventions for families experiencing social disadvantage: A meta-analysis. Prevention Science, 21(5), 714–727. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-020-01128-0

Hartling, L., Featherstone, R., Nuspl, M., Shave, K., Dryden, D. M., & Vandermeer, B. (2017). Grey literature in systematic reviews: A cross-sectional study of the contribution of non-English reports, unpublished studies and dissertations to the results of meta-analyses in child-relevant reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 17(1), 64–64. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-017-0347-z

Heber, E., Ebert, D. D., Lehr, D., Cuijpers, P., Berking, M., Nobis, S., & Riper, H. (2017). The benefit of web-and computer-based interventions for stress: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(2), e32.

Hemdi, A., & Daley, D. (2017). The Effectiveness of a Psychoeducation Intervention delivered via WhatsApp for mothers of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A randomized controlled trial. Child: Care, Health & Development, 43(6), 933–941. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12520

Higgins, J. P., & Thompson, S. G. (2002). Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Statistics in Medicine, 21(11), 1539–1558. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.1186

Higgins, J. P. T., Green, S., & Cochrane, C. (2011). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Cochrane Collaboration. http://handbook.cochrane.org/

James Riegler, L., Raj, S. P., Moscato, E. L., Narad, M. E., Kincaid, A., & Wade, S. L. (2020). Pilot trial of a telepsychotherapy parenting skills intervention for veteran families: Implications for managing parenting stress during COVID-19. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 30(2), 290–303. https://doi.org/10.1037/int0000220

Jamison, T. B., & Feistman, R. E. (2021). Understanding teen parents in a modern context: Prenatal hopes and postnatal realities. In R. Kuersten-Hogan & J. P. McHale (Eds.), Prenatal family dynamics: Couple and coparenting relationships during and postpregnancy (pp. 343–360). Springer.

Jones, S. H., Jovanoska, J., Calam, R., Wainwright, L. D., Vincent, H., Asar, O., Diggle, P. J., Parker, R., Long, R., Sanders, M., & Lobban, F. (2017). Web-based integrated bipolar parenting intervention for parents with bipolar disorder: A randomised controlled pilot trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(9), 1033–1041. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12745

Kaplan, K., Solomon, P., Salzer, M. S., & Brusilovskiy, E. (2014). Assessing an Internet-based parenting intervention for mothers with a serious mental illness: A randomized controlled trial. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 37(3), 222–231. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000080

Kierfeld, F., Ise, E., Hanisch, C., Görtz-Dorten, A., & Döpfner, M. (2013). Effectiveness of telephone-assisted parent-administered behavioural family intervention for preschool children with externalizing problem behaviour: A randomized controlled trial. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 22(9), 553–565. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-013-0397-7

Killgore, W. D. S., Cloonan, S. A., Taylor, E. C., Miller, M. A., & Dailey, N. S. (2020). Three months of loneliness during the COVID-19 lockdown. Psychiatry Research, 293, 113392–113392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113392

Kim, J. J., La Porte, L. M., Corcoran, M., Magasi, S., Batza, J., & Silver, R. K. (2010). Barriers to mental health treatment among obstetric patients at risk for depression. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 202(3), 312.e311–312.e315.

Kuhlthau, K. A., Luberto, C. M., Traeger, L., Millstein, R. A., Perez, G. K., Lindly, O. J., Chad-Friedman, E., Proszynski, J., & Park, E. R. (2019). A virtual resiliency intervention for parents of children with autism: A randomized pilot trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(7), 2513–2526. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-03976-4

Lecomte, T., Potvin, S., Corbière, M., Guay, S., Samson, C., Cloutier, B., Francoeur, A., Pennou, A., & Khazaal, Y. (2020). Mobile apps for mental health issues: Meta-review of meta-analyses. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 8(5), e17458–e17458. https://doi.org/10.2196/17458

Lefever, J. E. B., Bigelow, K. M., Carta, J. J., Borkowski, J. G., Grandfield, E., McCune, L., Irvin, D. W., & Warren, S. F. (2017). Long-term impact of a cell phone-enhanced parenting intervention. Child Maltreatment, 22(4), 305–314. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559517723125

Li, L. Z., & Wang, S. (2020). Prevalence and predictors of general psychiatric disorders and loneliness during COVID-19 in the United Kingdom. Psychiatry Research, 291, 113267–113267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113267

Love, S. M., Sanders, M. R., Turner, K. M. T., Maurange, M., Knott, T., Prinz, R., Metzler, C., & Ainsworth, A. T. (2016). Social media and gamification: Engaging vulnerable parents in an online evidence-based parenting program. Child Abuse and Neglect, 53, 95–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.10.031

Ma, L.-L., Wang, Y.-Y., Yang, Z.-H., Huang, D., Weng, H., & Zeng, X.-T. (2020). Methodological quality (risk of bias) assessment tools for primary and secondary medical studies: What are they and which is better? Military Medical Research, 7(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40779-020-00238-8

Maass, S. W. M. C., Roorda, C., Berendsen, A. J., Verhaak, P. F. M., & de Bock, G. H. (2015). The prevalence of long-term symptoms of depression and anxiety after breast cancer treatment: A systematic review. Maturitas, 82(1), 100–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.04.010

MacKenzie, E. P., & Hilgedick, J. M. (2000). The computer-assisted parenting program (CAPP): The use of a computerized behavioral parent training program as an educational tool. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 21(4), 23–43.

MacKinnon, A. L., Roos, L. E., Tomfohr-Madsen, L., Zalewski Regnier, M., Silang, K., & Penner, K. (2020). Promoting mental health in parents of young children using ehealth interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prospero. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=190719

Mascarenhas, M. N., Chan, J. M., Vittinghoff, E., Van Blarigan, E. L., & Hecht, F. (2018). Increasing physical activity in mothers using video exercise groups and exercise mobile apps: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(5), e179–e179. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.9310

Massoudi, B., Holvast, F., Bockting, C. L. H., Burger, H., & Blanker, M. H. (2019). The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of e-health interventions for depression and anxiety in primary care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 245, 728–743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.050

McFarland, J., Hussar, B., Zhang, J., Wang, X., Wang, K., Hein, S., Diliberti, M., Forrest Cataldi, E., Bullock Mann, F., & Barmer, A. (2019). The condition of education 2019. National Centre for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2019144

McLean, S. A., Booth, A. T., Schnabel, A., Wright, B. J., Painter, F. L., & McIntosh, J. E. (2021). Exploring the efficacy of telehealth for family therapy through systematic, meta-analytic, and qualitative evidence. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-020-00340-2

Mindell, J. A., Du Mond, C. E., Sadeh, A., Telofski, L. S., Kulkarni, N., & Gunn, E. (2011). Efficacy of an internet-based intervention for infant and toddler sleep disturbances. Sleep, 34(4), 451-458B.

Moghimi, M., Esmaeilpour, N., Karimi, Z., Zoladl, M., & Moghimi, M. A. (2018). Effectiveness of resilience teaching via short message service on stress of mothers of educable mentally retarded children. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 12(4), e59966. https://doi.org/10.5812/ijpbs.59966

Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., Shekelle, P., Stewart L. A., & PRISMA-P Group. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews, 4(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

Monaghan, M., Hilliard, M. E., Cogen, F. R., & Streisand, R. (2011). Supporting parents of very young children with type 1 diabetes: Results from a pilot study. Patient Education and Counseling, 82(2), 271–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2010.04.007

Neece, C., McIntyre, L. L., & Fenning, R. (2020). Examining the impact of COVID-19 in ethnically diverse families with young children with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 64(10), 739–749. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12769

Nicholson, J., Albert, K., Gershenson, B., Williams, V., & Biebel, K. (2009). Family options for parents with mental illnesses: A developmental, mixed methods pilot study. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 33(2), 106.

NIH. (2020). Study Quality Assessment Tools. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Retrieved September 8, 2020 from https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools

Osborn, R., Roberts, L., & Kneebone, I. (2020). Barriers to accessing mental health treatment for parents of children with intellectual disabilities: A preliminary study. Disability and Rehabilitation, 42(16), 2311–2317. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2018.1558460

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J., Bossuyt, P., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J., & Moher, D. (2020). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. MetaArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31222/osf.io/v7gm2

Păsărelu, C. R., Andersson, G., Bergman Nordgren, L., & Dobrean, A. (2017). Internet-delivered transdiagnostic and tailored cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 46(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2016.1231219

Patrick, S. W., Henkhaus, L. E., Zickafoose, J. S., Lovell, K., Halvorson, A., Loch, S., Letterie, M., & Davis, M. M. (2020). Well-being of parents and children during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national survey. Pediatrics, 146(4), e2020016824. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-016824

Patton, S. R., Clements, M. A., Marker, A. M., & Nelson, E. L. (2020). Intervention to reduce hypoglycemia fear in parents of young kids using video-based telehealth (REDCHiP). Pediatric Diabetes, 21(1), 112–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/pedi.12934

Paulson, J. F., & Bazemore, S. D. (2010). Prenatal and postpartum depression in fathers and its association with maternal depression: A meta-analysis. JAMA, 303(19), 1961–1969.

Penner-Goeke, L., Kaminski, L., Sulymka, J., Mitchell, B., Peters, S., & Roos, L. E. (2020). A meta-analysis group-based parenting programs for preschoolers: Are programs improving over time? https://psyarxiv.com/yubqs/

Phipps, S., Fairclough, D. L., Noll, R. B., Devine, K. A., Dolgin, M. J., Schepers, S. A., Askins, M. A., Schneider, N. M., Ingman, K., Voll, M., Katz, E. R., McLaughlin, J., & Sahler, O. J. Z. (2020). In-person vs. web-based administration of a problem-solving skills intervention for parents of children with cancer: Report of a randomized noninferiority trial. EClinicalMedicine, 24, 100428–100428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100428

Piotrowska, P. J., Tully, L. A., Collins, D. A. J., Sawrikar, V., Hawes, D., Kimonis, E. R., Lenroot, R. K., Moul, C., Anderson, V., Frick, P. J., & Dadds, M. R. (2020). ParentWorks: Evaluation of an online, father-inclusive, universal parenting intervention to reduce child conduct problems. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 51(4), 503–513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-019-00934-0

Potharst, E. S., Boekhorst, M. G. B. M., Cuijlits, I., van Broekhoven, K. E. M., Jacobs, A., Spek, V., Nyklíček, I., Bögels, S., & Pop, V. (2019). A randomized control trial evaluating an online mindful parenting training for mothers with elevated parental stress. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(JULY), 1550–1550. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01550

Rahman, A., Surkan, P. J., Cayetano, C. E., Rwagatare, P., & Dickson, K. E. (2013). Grand challenges: integrating maternal mental health into maternal and child health programmes. PLoS Medicine, 10(5), 1001442–1001446.

Raj, S. P., Antonini, T. N., Oberjohn, K. S., Cassedy, A., Makoroff, K. L., & Wade, S. L. (2015). Web-based parenting skills program for pediatric traumatic brain injury reduces psychological distress among lower-income parents. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 30(5), 347–356. https://doi.org/10.1097/HTR.0000000000000052

Rasic, D., Hajek, T., Alda, M., & Uher, R. (2014). Risk of mental illness in offspring of parents with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder: A meta-analysis of family high-risk studies. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 40(1), 28–38.

Rayner, M., Dimovski, A., Muscara, F., Yamada, J., Burke, K., McCarthy, M., Hearps, S. J. C., Anderson, V. A., Coe, A., Hayes, L., Walser, R., & Nicholson, J. M. (2016). Participating from the comfort of your living room: feasibility of a group videoconferencing intervention to reduce distress in parents of children with a serious illness or injury. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 38(3), 209–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317107.2016.1203145

Sairanen, E., Lappalainen, R., Lappalainen, P., & Hiltunen, A. (2020). Mediators of change in online acceptance and commitment therapy for psychological symptoms of parents of children with chronic conditions: An investigation of change processes. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 15, 123–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2019.11.010

Sanders, M., Calam, R., Durand, M., Liversidge, T., & Carmont, S. A. (2008). Does self-directed and web-based support for parents enhance the effects of viewing a reality television series based on the Triple P - Positive Parenting Programme? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(9), 924–932. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01901.x

Sanders, M. R., Dittman, C. K., Farruggia, S. P., & Keown, L. J. (2014). A comparison of online versus workbook delivery of a self-help positive parenting program. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 35(3), 125–133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-014-0339-2

Schardt, C., Adams, M. B., Owens, T., Keitz, S., & Fontelo, P. (2007). Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 7, 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-7-16

Semega, J., Kollar, M. A., Shrider, E. A., & Creamer, J. (2020). Income and poverty in the United States: 2019 (P60-270). https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2020/demo/p60-270.html

Sheeber, L. B., Feil, E. G., Seeley, J. R., Leve, C., Gau, J. M., Davis, B., Sorensen, E., & Allan, S. (2017). Mom-Net: Evaluation of an Internet-facilitated cognitive behavioral intervention for low-income depressed mothers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(4), 355–366. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000175

Sheeber, L. B., Seeley, J. R., Feil, E. G., Davis, B., Sorensen, E., Kosty, D. B., & Lewinsohn, P. M. (2012). Development and pilot evaluation of an Internet-facilitated cognitive-behavioral intervention for maternal depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(5), 739–749. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028820

Skranes, L. P., Løhaugen, G. C. C., & Skranes, J. (2015). A child health information website developed by physicians: The impact of use on perceived parental anxiety and competence of Norwegian mothers. Journal of Public Health, 23(2), 77–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-015-0659-6

Smith, M. S., Lawrence, V., Sadler, E., & Easter, A. (2019). Barriers to accessing mental health services for women with perinatal mental illness: systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative studies in the UK. British Medical Journal Open, 9(1), e024803.

Sourander, A., McGrath, P. J., Ristkari, T., Cunningham, C., Huttunen, J., Lingley-Pottie, P., Hinkka-Yli-Salomäki, S., Kinnunen, M., Vuorio, J., & Sinokki, A. (2016). Internet-assisted parent training intervention for disruptive behavior in 4-year-old children: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 73(4), 378–387.

Spencer, C. M., Topham, G. L., & King, E. L. (2020). Do online parenting programs create change? A meta-analysis. Journal of Family Psychology, 34(3), 364–374. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000605

Steinert, C., Stadter, K., Stark, R., & Leichsenring, F. (2017). The effects of waiting for treatment: A meta-analysis of waitlist control groups in randomized controlled trials for social anxiety disorder. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 24(3), 649–660. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2032

Stroup, D. F., Berlin, J. A., Morton, S. C., Olkin, I., Williamson, G. D., Rennie, D., Moher, D., Becker, B. J., Sipe, T. A., & Thacker, S. B. (2000). Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: A proposal for reporting. JAMA, 283(15), 2008–2012.

Sveen, J., Andersson, G., Buhrman, B., Sjöberg, F., & Willebrand, M. (2016). Internet-based information and support program for parents of children with burns: A randomized controlled trial. Burns, 43(3), 583–591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2016.08.039

Thongseiratch, T., Leijten, P., & Melendez-Torres, G. J. (2020). Online parent programs for children’s behavioral problems: A meta-analytic review. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 29(11), 1555–1568. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01472-0

Wade, C. M., Ortiz, C., & Gorman, B. S. (2007). Two-session group parent training for bedtime noncompliance in head start preschoolers. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 29(3), 23–55. https://doi.org/10.1300/J019v29n03_03

Wampold, B. E. (2015). The great psychotherapy debate : The evidence for what makes psychotherapy work (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Wang, J., Howell, D., Shen, N., Geng, Z., Wu, F., Shen, M., Zhang, X., Xie, A., Wang, L., & Yuan, C. (2018). mHealth supportive care intervention for parents of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Quasi-experimental pre- and postdesign study. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 6(11), e195–e195. https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.9981

Whitney, R. V., & Smith, G. (2015). Emotional disclosure through journal writing: Telehealth intervention for maternal stress and mother–child relationships. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(11), 3735–3745. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2332-2

World Health Organization. (1993). The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: Diagnostic criteria for research. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/37108

World Health Organization. (2011). mHealth: new horizons for health through mobile technologies. World Health Organization.

Wright, K. D. P. D., Raazi, M. M. D. F., & Walker, K. L. M. A. (2017). Internet-delivered, preoperative, preparation program (I-PPP): Development and examination of effectiveness. Journal of Clinical Anesthesia, 39, 45–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinane.2017.03.007

Zhao, L., Chen, J., Lan, L., Deng, N., Liao, Y., Yue, L., Chen, I., Wen, S. W., & Xie, R.-H. (2021). Effectiveness of telehealth interventions for women with postpartum depression: Systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 9(10), e32544. https://doi.org/10.2196/32544

Zhou, C., Hu, H., Wang, C., Zhu, Z., Feng, G., Xue, J., & Yang, Z. (2020). The effectiveness of mHealth interventions on postpartum depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X20917816

Acknowledgements

For consultation on the database search strategy, we thank Dr. Zahra Premji, PhD MLIS, Research and Learning Librarian, University of Calgary. For consultation on the data analysis approach, we thank Dr. Paul Ronksley, PhD, Department of Community Health Sciences, University of Calgary. Dr. MacKinnon was supported by a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) Postdoctoral Fellowship (756-2019-0669).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interests to declare.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

MacKinnon, A.L., Silang, K., Penner, K. et al. Promoting Mental Health in Parents of Young Children Using eHealth Interventions: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 25, 413–434 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-022-00385-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-022-00385-5