Abstract

The aim of this work was to compare the effects on human amniotic membrane of freeze-drying and γ-irradiation at doses of 10, 20 and 30 kGy, with freezing. For this purpose, nine cytokines (interleukin 10, platelet-derived growth factor-AA, platelet-derived growth factor-BB, basic fibroblast growth factor, epidermal growth factor, transforming growth factor beta 1, and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase-1, -2, and -4) were titrated in 5 different preparations for each of 3 amniotic membranes included in the study. In addition, the extracellular matrix structure of each sample was assessed by transmission electron microscopy. While freeze-drying did not seem to affect the biological structure or cytokine content of the different amniotic membrane samples, γ-irradiation led to a significant decrease in the tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase-4, basic fibroblast growth factor and epidermal growth factor, and induced structural damage to the epithelium, basement membrane and lamina densa. The higher the irradiation dose the more severe the damage to the amniotic membrane structure. In conclusion, the Authors recommend processing amniotic membrane under sterile conditions to guarantee safety at every step rather than final sterilization with γ-irradiation, thereby avoiding alteration to the biological characteristics of the amniotic membrane.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Human amniotic membrane (HAM) has been used in a variety of surgical procedures. First employed in skin transplantation by (Davis 1910), HAM was subsequently found to be useful as a biological wound dressing for burns (Ramakrishnan and Jayaraman 1997; Branski et al. 2008), acute (Tekin et al. 2008) and chronic wounds (Gajiwala and Lobo 2003; Insausti et al. 2010), and in the reconstruction of the dura mater (Tomita et al. 2012; De Weerd et al. 2013), oral cavity (Lawson 1985), vaginal vault (Ashworth et al. 1986), tendons (Ozbölük et al. 2010) and nerves (O’Neill et al. 2009). HAM has also long been used in ophthalmic surgery, the earliest reported application being in 1940 when De Rötth used fetal membranes to correct symblepharon (De Rötth 1940). Today HAM is widely used for ocular surface reconstruction and treating several important ocular diseases (Paolin et al. 2016). All these applications are possible because HAM has anti-inflammatory, antifibrotic properties (Solomon et al. 2001; Tseng et al. 1999).

Hao et al. have shown that human amniotic epithelial and mesenchymal cells both express interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, all the four tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase (TIMPs), collagen XVIII, and interleukin-10 (Hao 2000). Moreover, reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) has shown that HAM expresses several additional cytokines, such as transforming growth factor (TGF-α, -β1, -β2), epidermal growth factor (EGF), keratinocyte growth factor (KGF), basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), keratinocyte growth factor receptor (KGFR), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and hepatocyte growth factor receptor (HGFR) (Koizumi et al. 2000; Li et al. 2005; Gicquel et al. 2009).

Since these factors may contribute to the clinical outcomes of HAM implants, several studies have endeavored to evaluate the effects of HAM storage conditions on their content and cell viability (Hennerbichler et al. 2007, Wolbank et al. 2009).

To date, the methods adopted for HAM storage are freezing at −80 °C (Mermet et al. 2007) or at −196 °C in liquid nitrogen vapor (Alió et al. 2005), and freeze-drying (Rahman et al. 2009; Riau et al. 2010).

In 2001, Adds et al. reported no differences in terms of clinical results between fresh and frozen HAM, both preparations resulting in improved visual acuity. Furthermore, fresh tissue performed no better than frozen tissue in promoting re-epithelialization (Adds et al. 2001). It has, however, been demonstrated that different processing, storage and sterilization methods do affect HAM properties. (von Versen-Höynck et al. 2004).

Rodriguez-Ares et al. studied the effects of freeze-drying and cryopreservation on HAM histological characteristics and protein levels. The authors found that although lyophilization does not affect the histological structure of HAM, it seems to reduce growth factor concentration more than cryopreservation (Rodriguez-Ares et al. 2009). Ricci et al. demonstrated that cryopreservation maintains the anti-fibrotic properties of HAM when used as a patch to reduce the severity of liver fibrosis (Ricci et al. 2013). Freeze-dried HAM does, however, have the advantage of allowing storage and shipment at room temperature, making handling much easier.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of γ-irradiation on cytokine levels and the ultrastructure of the extracellular matrix of different HAM preparations.

Accordingly, we a) carried out a quantitative measurement of the following cytokines: interleukin 10 (IL-10), platelet-derived growth factor-AA (PDGF-AA), platelet-derived growth factor-BB (PDGF-BB), basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), epidermal growth factor (EGF), transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF-β1), tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1), -2 (TIMP-2), and -4 (TIMP-4), and b) analyzed each HAM preparation with transmission electron microscopy.

Materials and methods

HAM collection and processing

Three placentas were sourced from elective cesarean sections after obtaining written informed consent in hospitals belonging to our tissue bank procurement network. Donors were selected on the basis of strict criteria that also include guidelines for harvesting, processing and distributing tissues for transplantation as approved by the National Transplant Centre. Selection criteria included the absence of any kind of malignancy, infant malformation or pathology, a gestation period of at least 35 weeks, negative family medical history for genetic diseases, and lifestyles of both parents not at risk for infectious diseases. On arrival at the bank the tissues were anonymized with a unique code number used for all processing phases.

Working in sterile conditions in a laminar flow cabinet within 24 h of tissue retrieval, HAM was carefully detached from the chorion and rinsed with saline solution to remove blood clots.

After processing, HAM underwent microbiological testing to ascertain its sterility and was frozen at -80 °C without cryprotectant. Prior to the study the HAM specimens were thawed, rinsed in saline solution and sterile water. Each HAM specimen was cut into 5 samples referred to as follows: a) “fresh-frozen” (one sample): left unprocessed, b) “freeze-dried” (one sample): freeze-dried, and c) “γ-irradiated” (3 samples): freeze-dried and sterilized with γ-irradiation at doses of 10, 20 and 30 kGy respectively.

The study design was not submitted to our ethical committee as consent had already been given for both clinical and research purposes.

Cytokine quantitative assessment

A specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (R&D Human Immunoassay) was used for each cytokine, as shown in Table 1.

The assay employs the quantitative sandwich enzyme immunoassay technique whereby an antibody specific for each cytokine is pre-coated onto a microplate. The analysis was performed twice for each cytokine, in triplicate. Samples were re-suspended in Triton X-100 lysis buffer (20 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 10 % glycerol, 1 % Triton X-100, and Complete Protease Inhibitor mixture) and placed on ice for 30 min, after which, the extracts were centrifuged for 30 min at 14,000 × g at 4 °C to remove debris before performing the ELISA assays. The ELISA assays were performed in compliance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The total protein content of each sample was determined by the Bradford protein assay and used to normalize the total cytokine concentration.

Microscopic and ultrastructural analysis

Small formalin-fixed HAM samples were embedded in paraffin and stained with Hematoxylin-Eosin (Orlandi et al. 2005). For transmission electron microscopy, small reconstituted samples were fixed overnight in Karnovsky fixative containing 2 % glutaraldehyde, 2 % paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4), post-fixed in 1 % OsO4 for 2 h and dehydrated through an alcohol series and propylene oxide before embedding in EPON 812, as reported (Spagnoli et al. 1995). Ultrathin sections were cut with an 8800 ultramicrotome III (LKB, Bromma, Sweden), counterstained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and studied under a Hitachi electron microscope.

Statistical analysis

Student’s t test was used to compare the different cytokine levels present in the different HAM preparations. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Quantitative cytokine measurements

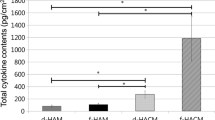

The numerical content of cytokines in pg/mg for each HAM preparation and their percentage variations versus fresh-frozen samples are shown in Table 2. Figure 1 presents these data in histogram form.

Compared to fresh-frozen samples, TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 levels were not significantly affected either by freeze-drying or irradiation, even though the 30 kGy γ-irradiated HAMs showed a 22 % fall in TIMP-1 and a 35 % decrease for TIMP-2 levels. Moreover, the fall in TIMP-1 content was observed in only one of the three samples and was not statistically significant. Compared to fresh-frozen HAM, TIMP-4 was significantly lower (−66 %) in 10 kGy-irradiated HAM samples (p < 0.05*), and in 20 and 30 kGy irradiated HAMs (p < 0.01**; −74 and −81 % respectively).

The highest γ-irradiation dose caused a 69 %, statistically significant, decrease in bFGF (p < 0.05*) versus fresh-frozen samples, whereas low-dose irradiation and freeze-drying did not significantly affect bFGF content in any HAM preparation.

EGF levels fell significantly by 57 and 76 % respectively following 20 kGy (p < 0.05*) and 30 kGy (p < 0.01**) irradiation, in contrast to the lowest-dose irradiation and freeze-drying, which did not significantly affect EGF levels compared to fresh-frozen samples.

Compared to the fresh-frozen samples, PDGF-AA and PDGF-BB levels were not significantly affected by either freeze-drying or irradiation, even if 30 kGy γ-irradiated HAM samples were found to have 65 % less PDGF-AA and 23 % less PDGF-BB compared to the fresh-frozen samples.

Lastly, IL-10 and TGFβ-1 concentrations were not significantly affected either by irradiation or freeze-drying in any samples.

Ultrastructural analysis and HAM damage

Figure 2 shows representative ultrastructural images of different HAM samples. The transmission electron microscopy images in Fig. 2a–c show fresh-frozen HAM samples to have well-preserved epithelium, with the presence of apical microvilli, cytoplasmic vacuoles and basement membrane. Electrondense structures and hemidesmosomes are also visible. The collagen matrix morphology of the basal lamina is also fairly well preserved. In the images Fig. 2d–f, taken after freeze-drying, the epithelium, microvilli, vacuoles, electron-dense structures, basement membrane, and hemidesmosomes are still visible. Nuclear changes can be seen while the collagen matrix morphology of the basal lamina is largely preserved. One sample (Fig. 2d) shows more severe tissue damage, with the epithelium and basement membrane no longer visible. Samples exposed to 10 kGy irradiation (Fig. 2g–i) display surface epithelium with loss of microvilli, intracytoplasmic vacuoles, electron-dense structures and nuclear degenerative changes. The basement membrane also appears thinner and there are fewer hemidesmosomes. However, the collagen matrix of the lamina densa is preserved. In one sample (Fig. 2g), the changes are more severe: no epithelium or basement membrane is visible and the collagen matrix of the lamina densa is degenerated and markedly disrupted. The three images of samples exposed to 20 kGy irradiation (Fig. 2l–n) evidence no epithelium or basement membrane in two of the three specimens. The collagen matrix of the lamina densa is poorly preserved and almost degenerated. In the image of the third 20 kGy-irradiated sample (Fig. 2m), the epithelium, cytoplasmic vacuoles and electron-dense structures are partially preserved, but degenerative nuclear changes can be observed. However, the basement membrane and hemidesmosomes are preserved. 2 of the 3 samples exposed to 30 kGy irradiation (Fig. 2o–q) show no epithelium or basement membrane, whereas one sample evidences only a thinning of these structures; the collagen matrix of the lamina densa is, however, thinner and abnormal. Almost complete homogenization of the cell surface layer can be seen in two examples.

Discussion

Our findings show that all the cytokines analyzed were present in fresh-frozen samples and were still present after freeze-drying, whereas sterilization of HAM by exposure to γ-radiation led to significant cytokine losses. Moreover, sterilization by γ-irradiation proportionally affected the ECM ultrastructure, indicative that the higher the irradiation dose, the more severe the ECM damage.

The cytokines analyzed in this study are among those most frequently indicated in the literature as involved in wound healing and tissue regeneration processes.

TIMP-1, -2 and -4 are inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), a group of peptidases involved in degradation of the ECM. In addition to their inhibitory role, TIMPs promote cell proliferation in a wide range of cell types, and may also have an anti-apoptotic function. Basic FGF is a potent angiogenic factor and an endothelial cell mitogen, and has been described as a multipotent cytokine regulating cell growth and differentiation, matrix composition, chemotaxis, cell adhesion and migration in a variety of cell types (Makino et al. 2010). bFGF is known to stimulate proliferation of cultured fibroblasts.

Members of the PDGF family are mitogenic factors for cells of mesenchymal origin. PDGF-BB modulates endothelial proliferation and angiogenesis (Battegay et al. 1994), while IL-10, secreted by macrophages and mast cells, is an important immunoregulatory cytokine with anti-inflammatory effects. IL-10 is also released by cytotoxic T cells to inhibit viral infection (Khan 2008). TGF-β1 and EGF both play an important role in the growth, proliferation and differentiation of numerous cell types. In particular, EGF is a potent mitogen for epithelial cell growth, promoting wound healing following transplantation (Koizumi et al. 2000).

Our results showed the various TIMPs to have differing sensitivity to gamma-irradiation. This may be due to several reasons, including, for example, being part of a protein complex, which reduces the likelihood of being affected by radiation. The different amino acid content of the three proteins may also contribute to determining sensitivity to radiation. In this regard, one of the main targets of radiation is the amino acid tyrosine. Interestingly, TIMP-4 contains twice as much tyrosine as TIMP-1 and -2, which may explain why TIPM-4 is more sensitive to radiation treatment than TIMP-1/-2. It is also possible, however, that gamma irradiation directly affects the immunogenic structure of TIMP-4 and EGF, disrupting specific epitope(s) recognized by the antibodies used in the ELISA Kit. A similar effect may also be present in other cytokines. However, if the affected epitope(s) is not recognized by the kit antibodies, no difference in protein content will detected. It should also be noted that the experiments conducted were confined to detecting the presence of the proteins and not their biological function. Differences in the observed concentration of the various TIMPs might not reflect actual biological activity. The same hypothesis also applies to the other cytokines, such as EGF, whose levels fell significantly following radiation treatment.

While the literature reports many studies describing HAM composition after different preservation procedures, the many differences in HAM harvesting and processing methods make comparisons almost impossible. Hao et al. demonstrated that HAM epithelial and mesenchymal cells cryopreserved in glycerol at −80 °C express interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, all four TIMPs, collagen XVIII, and interleukin-10 (Hao 2000). Other authors used the same preservation method and found HAM to contain EGF, TGFα, KGH, HGF, bFGF, TGF-β1, and -β2 (Li et al. 2005). Another paper analyzed EGF, HGF, FGF, and TGF-β1 content in a tissue-suspension obtained from frozen, freeze-dried, powdered and γ-irradiated HAM, reporting that the freeze-drying process causes a reduction in total protein compared to freezing alone, while powdering causes a significantly increased release of EGF (Russo et al. 2012). Lim et al. compared decellularized and dehydrated human amniotic membrane with cryopreserved human amniotic membrane, and reported significant differences in the composition and ultrastructure of dehydrated HAM as shown by histological and immunohistochemical examination (Lim et al. 2010). Nakamura et al. reported no statistically significant differences in the physical strength of cryopreserved HAM or freeze-dried HAM treated with γ-irradiation. The authors also observed no significant alterations in tissue structure or ECM components (Nakamura et al. 2004).

Ultrastructural analysis provided additional evidence of the damage caused by γ-rays, in contrast to the absence of any severe damage evidenced in fresh-frozen and freeze-dried samples. γ-irradiation induced major damage to the epithelium, basement membrane and lamina densa, which was more severe after exposure to 20 and 30 kGy γ-irradiation.

Preservation of the epithelium structure is of major importance since epithelial cells express key anti-inflammatory factors as reported by Hao (2000).

Exposure to γ-radiation is known to induce cellular and sub-cellular damage. Radiation has a direct effect, interacting with the structures of the target to cause ionization and subsequent biological changes (Valentin 2005; Lehnert 2007) and also an indirect action, that can lead to the production of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), which in turn, may induce important membrane changes and cellular injury, with an increase in polarization at higher radiation doses (>3 kGy; Mishra 2004).

In 2014, Hamid et al. demonstrated changes to the cell morphology of glycerol-preserved amnion exposed to 35 kGy, while air-dried HAM underwent changes at 25 kGy. and concluded, that cell structure preservation of glycerol-preserved amnion after radiation is probably due to the radio-protectant properties of glycerol, which removes water and limits the formation of free radicals (Ab Hamid et al. 2014).

In our study, we observed that γ-radiation causes important changes in the amniotic epithelium, basal lamina and basement membrane. In addition, we detected the loss of important cytokines necessary to promote wound healing and epithelialization, inhibit fibrosis and scarring, and regulate angiogenesis. In contrast, we also demonstrated that cytokine levels and the amniotic structure-key features responsible for the favorable clinical outcomes obtained with HAM-were well preserved only in fresh-frozen and freeze-dried HAM samples.

In conclusion, processing the amniotic membrane under sterile conditions to guarantee safety at every step as an alternative to final sterilization with γ-irradiation is strongly recommended in order to avoid alteration of the biological characteristics of the amniotic membrane.

References

Ab Hamid SS, Zahari NK, Yusof N, Hassan A (2014) Scanning electron microscopic assessment on surface morphology of preserved human amniotic membrane after gamma sterilization. Cell Tissue Bank 15(1):15–24

Adds PJ, Hunt CJ, Dart JK (2001) Amniotic membrane grafts, ‘fresh’ or frozen? A clinical and in vitro comparison. Br J Ophthalmol 85(8):905–907

Alió JL, Abad M, Scorsetti DH (2005) Preparation, indications and results of human amniotic membrane transplantation for ocular surface disorders. Expert Rev Med Devices 2(2):153–160

Ashworth MF, Morton KE, Dewhurst J, Lilford RJ, Bates RG (1986) Vaginoplasty using amnion. Obstet Gynecol 67(3):443–446

Battegay EJ, Rupp J, Iruela-Arispe L, Sage EH, Pech M (1994) PDGF-BB modulates endothelial proliferation and angiogenesis in vitro via PDGF beta-receptors. J Cell Biol 125(4):917–928

Branski LK, Herndon DN, Celis MM, Norbury WB, Masters OE, Jeschke MG (2008) Amnion in the treatment of pediatric partial-thickness facial burns. Burns 34(3):393–399

Davis JW (1910) Skin transplantation with a review of 550 cases at the Johns Hopkins Hospital. Johns Hopkins Med J. 15:307

de Rötth A (1940) Plastic repair of conjunctival defects with fetal membranes. Arch Ophthalmol 23:522–525

de Weerd L, Weum S, Sjavik K, Acharya G, Hennig RO (2013) A new approach in the repair of a myelomeningocele using amnion and a sensate perforator flap. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 66(6):860–863

Gajiwala K, Lobo Gajiwala A (2003) Use of banked tissue in plastic surgery. Cell Tissue Bank 4(2–4):141–146

Gicquel JJ, Dua HS, Brodie A, Mohammed I, Suleman H, Lazutina E et al (2009) Epidermal growth factor variations in amniotic membrane used for ex vivo tissue constructs. Tissue Eng Part A 15(8):1919–1927

Hao Y (2000) Identification of antiangiogenic and antiinflammatory proteins in human amniotic membrane. Cornea 19(3):348–352

Hennerbichler S, Reichl B, Pleiner D, Gabriel C, Eibl J, Redl H (2007) The influence of various storage conditions on cell viability in amniotic membrane. Cell Tissue Bank 8(1):1–8

Insausti CL, Alcaraz A, García-Vizcaíno EM, Mrowiec A, López-Martínez MC, Blanquer M et al (2010) Amniotic membrane induces epithelialization in massive posttraumatic wounds. Wound Repair Regen Jul-Aug 18(4):368–377

Khan MM (2008) Immunopharmacology, Springer Science + Business Media. LLC. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-77976-8.2

Koizumi NJ, Inatomi TJ, Sotozono CJ, Fullwood NJ, Quantock AJ, Kinoshita S (2000) Growth factor mRNA and protein in preserved human amniotic membrane. Curr Eye Res 20(3):173–177

Lawson VG (1985) Oral cavity reconstruction using pectoralis major muscle and amnion. Arch Otolaryngol. 111(4):230–233

Lehnert S (2007) Biomolecular Action of Ionizing Radiation, Taylor and Francis Group, LLC

Li H, Niederkorn JY, Neelam S, Mayhew E, Word RA, McCulley JP et al (2005) Immunosuppressive factors secreted by human amniotic epithelial cells. Invest Ophth Vis Sci. 46(3):900–907

Lim LS, Poh RW, Riau AK, Beuerman RW, Tan D, Mehta JS (2010) Biological and Ultrastructural Properties of Acelagraft, a Freeze-Dried γ-Irradiated Human Amniotic Membrane. Arch Ophthalmol 128(10):1303–1310

Makino T, Jinnin M, Muchemwa FC, Fukushima S, Kogushi-Nishi H, Moriya C et al (2010) Basic fibroblast growth factor stimulates the proliferation of human dermal fibroblasts via the ERK1/2 and JNK pathways. Br J Dermatol 162(4):717–723

Mermet I, Pottier N, Sainthillier JM, Malugani C, Cairey-Remonnay S, Maddens S (2007) Use of amniotic membrane transplantation in the treatment of venous leg ulcers. Wound Repair Regen Jul-Aug 15(4):459–464

Mishra KP (2004) Cell Membrane oxidative damage induced by gamma-radiation and apoptotic sensitivity. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol 23(1):61–66

Nakamura T, Yoshitani M, Rigby H, Fullwood NJ, Ito W, Inatomi T et al (2004) Sterilized, freeze-dried amniotic membrane: a useful substrate for ocular surface reconstruction. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 45:93–99

O’Neill AC, Randolph MA, Bujold KE, Kochevar IE, Redmond RW, Winograd JM (2009) Preparation and integration of human amnion nerve conduits using a light activated technique. Plast Reconstr Surg 124(2):428–437

Orlandi A, Ciucci A, Ferlosio A, Pellegrino A, Chiariello L, Spagnoli LG (2005) Increased expression and activity of matrix metalloproteinases characterize embolic cardiac myxomas. Am J Pathol 166:1619–1628

Ozbölük S, Ozkan Y, Oztürk A, Gül N, Ozdemir RM, Yanik K (2010) The effects of human amnion membrane and periosteal autograft on tendon healing: experimental study in rabbits. J Hand Surg Eur 35(4):262–268

Paolin A, Cogliati E, Trojan D, Griffoni C, Grassetto A, Elbadawy HM, Ponzin D (2016) Amniotic membranes in ophthalmology: long term data on transplantation outcomes. Cell Tissue Bank. 17(1):51–58

Rahman I, Said DG, Maharajan VS, Dua HS (2009) Amniotic membrane in ophthalmology: indications and limitations. Eye. 23(10):1954–1961

Ramakrishnan KM, Jayaraman V (1997) Management of partial-thickness burn wounds by amniotic membrane: a cost-effective treatment in developing countries. Burns. 23(Suppl 1):S33–S36

Riau AK, Beuerman RW, Lim LS, Mehta JS (2010) Preservation, sterilization and de-epithelialization of human amniotic membrane for use in ocular surface reconstruction. Biomaterials 31(2):216–225

Ricci E, Vanosi G, Lindenmair A, Hennerbichler S, Peterbauer-Scherb A, Wolbank S, Cargnoni A, Signoroni PB, Campagnol M, Gabriel C, Redl H, Parolini O (2013) Anti-fibrotic effects of fresh and cryopreserved human amniotic membrane in a rat liver fibrosis model. Cell Tissue Bank. 14(3):475–488

Rodriguez-Ares MT, López-Valladares MJ, Touriño R, Vieites B, Gude F, Silva MT (2009) Effects of lyophilization on human amniotic membrane. Acta Ophthalmol 87(4):396–403

Russo A, Bonci P, Bonci P (2012) The effects of different preservation processes on the total protein and growth factor content in a new biological product developed from human amniotic membrane. Cell Tissue Bank. 13(2):353–361

Solomon A, Rosenblatt M, Monroy D, Ji Z, Pflugfelder SC, Tseng SC (2001) Suppression of interleukin 1alpha and interleukin 1beta in human limbal epithelial cells cultured on the amniotic membrane stromal matrix. Br J Ophthalmol 85(4):444–449

Spagnoli LG, Orlandi A, Marino B, Mauriello A, De Angelis C, Ramacci MT (1995) Propionyl-L-carnitine prevents the progression of atherosclerotic lesions in aged hyperlipemic rabbits. Atherosclerosis. 114(1):29–44

Tekin S, Tekin A, Kucukkartallar T, Cakir M, Kartal A (2008) Use of chorioamniotic membrane instead of bogota bag in open abdomen: how i do it? World J Gastroenterol 14(5):815–816

Tomita T, Hayashi N, Okabe M, Yoshida T, Hamada H, Endo S et al (2012) New dried human amniotic membrane is useful as a substitute for dural repair after skull base surgery. J Neurol Surg B. Skull Base. 73(5):302–307

Tseng SC, Li DQ, Ma X (1999) Suppression of transforming growth factor-beta isoforms, TGF-beta receptor type II, and myofibroblast differentiation in cultured human corneal and limbal fibroblasts by amniotic membrane matrix. J Cell Physiol 179(3):325–335

Valentin J (2005) Low-dose Extrapolation of Radiation-Related Cancer Risk. Ann ICRP. 35(4):1–140

von Versen-Höynck F, Syring C, Bachmann S, Möller DE (2004) The influence of different preservation and sterilization steps on the histological properties of amnion allografts–light and scanning electron microscopic studies. Cell Tissue Bank 5(1):45–56

Wolbank S, Hildner F, Redl H, Van Griensven M, Gabriel C, Hennerbichler S (2009) Impact of human amniotic membrane preparation on release of angiogenic factors. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 3(8):651–654

Acknowledgments

Our thanks go to Dr. Chiara Romualdi of Padova University for the statistical analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Paolin, A., Trojan, D., Leonardi, A. et al. Cytokine expression and ultrastructural alterations in fresh-frozen, freeze-dried and γ-irradiated human amniotic membranes. Cell Tissue Bank 17, 399–406 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10561-016-9553-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10561-016-9553-x