Abstract

Although sub-Saharan Africa has the world’s highest rates of early pregnancy, there is little awareness of pregnancy and parenting among young people in out-of-home care in this region. Therefore, this study looked into the experiences of pregnancy and parenting among young women who had been in residential care in Ghana and Uganda. We gathered data from ten parenting care leavers in both countries using semi-structured interviews and then analyzed the data from the interviews thematically. The study’s findings revealed that the young mothers had minimal sexual and reproductive health education, as well as a lack of sufficient monitoring, which predisposed them to early pregnancy. The young mothers indicated that emotional stress, financial and employment obstacles, as well as stigma, were some challenges they had experienced. They used personal motivation and spirituality as coping mechanisms to deal with their challenges. Training caregivers to deliver sexual and reproductive health information, having practitioners who will offer supervision during the semi-independent phase of leaving care, and providing separate housing for young mothers are some implications for practice emerging from the study. Policy implications include the need for social inclusion programs to support the academic, vocational, and parenting skills of young mothers who leave care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Adolescent pregnancy is on the decline in developed countries like the United States and the United Kingdom, but there is evidence that children in residential or foster care and care leavers are more likely to get pregnant and become parents at an early age (Albertson et al., 2020; Font et al., 2019; Harmon-Darrow et al., 2020; Oshima et al., 2013; Shpiegel et al., 2021). Several factors contribute to the high rate of teenage pregnancy and motherhood among adolescents in foster care. Young people in care commonly lack awareness of and access to sexual and reproductive health (SRH) information and services, according to Harmon-Darrow et al. (2020). They also miss out on sex education in school or SRH counseling from a trusted adult due to frequent placement changes (King & Van Wert, 2017). Time constraints, a lack of expertise, and the emotional weight of discussing SRH are all issues that prevent caregivers from giving SRH education to children and adolescents in care (Nixon et al., 2019).

According to the literature, youth in care are more likely to participate in unsafe sex, early sexual debut, and have many partners, which may explain some of the early pregnancies witnessed among this population (Ahrens et al., 2013; Botchway et al., 2014). The high rate of early pregnancy among foster care youth is also a result of their desire to create families of their own to fill the emotional void of absent meaningful relationships and attachments (Datta et al., 2017; Purtell et al., 2020; Rouse et al., 2021).

Pregnant and parenting youth in and out of care face several challenges. In terms of health, teenage mothers are prone to stress and postpartum depression (Kingston et al., 2012). These mental health issues, along with a lack of support, raise the risk of women assaulting their children, which results in the state sometimes removing their children and placing them in foster care or for adoption (Roberts et al., 2017). Being pregnant or a parent adds to the difficulties faced by youth transitioning out of care, as they often experience poor educational performance, homelessness, substance abuse, and unemployment (Combs et al., 2018; Radey et al., 2016; Schelbe & Geiger, 2017). Other difficulties they encounter include societal stigma, criticism of their parenting abilities, and a lack of social support (Bermea et al., 2018; Eastman et al., 2019; Schelbe & Geiger, 2017).

Despite these difficulties, pregnant and parenting young people with an experience of out-of-home care do not view their experiences entirely negatively. For some, parenting is a source of pride and associated with a sense of optimism and a source of identity (Aparicio et al., 2015). As a result, many demonstrate tenacity in breaking the intergenerational cycle of their children being placed in foster care. They endeavor to be good parents and strive to provide their children with a life distinct from their own (Coler, 2018; Roberts et al., 2019; Schelbe & Geiger, 2017).

Some studies indicate that raising the legal age for leaving care may reduce the number of early pregnancies (Dworsky & Courtney, 2010; Font et al., 2019; Putnam-Hornstein et al., 2016). Extending young people’s stay in care, according to these authors, give young people access to specialized pregnancy prevention interventions and assistance. Pregnancy prevention and parenting support interventions addressing the needs of youth in care and those out of care include home visiting interventions and parenting groups that provide psychological, social, and financial support (Eastman et al., 2019). According to Albertson et al. (2020), trusted relationships with an adult (e.g., primary caregivers) reduces the prevalence of early pregnancy among this population of youth.

The world's highest rate of early pregnancy is in sub-Saharan Africa, with Ghana averaging 75 per 1000 births and Uganda averaging 132 per 1000 births (UNFPA, 2021; UNICEF, 2019). Moreover, relatively limited evidence from both nations suggests that girls in care are at higher risk than girls who are not in care (Ddumba-Nyanzi et al., 2020; Frimpong-Manso, 2012). Despite this situation, to the best of our knowledge, there is hardly any African research on the experiences of pregnant and parenting young women in and out of care. This paper contributes to the existing literature by investigating the parenting experiences of young women who have left care in Ghana and Uganda. Specifically, the study looks into the factors that lead to early pregnancies among these young mothers, the challenges they encounter, and the coping techniques used to deal with their challenges. We conducted this research to identify the common themes that can inform policy and practice in the two countries and other comparable contexts.

Rationale of the Study

Ghana and Uganda, both low-income countries in sub-Saharan Africa, have populations of 30 million and 43 million people, respectively, with children and young people being the majority (UNFPA, 2021). Most children and young people who receive state care in residential facilities do so because of poverty and other socioeconomic situations. Ghana has 3530 children and young people living in 139 residential care facilities (Ghana Department of Social Welfare & UNICEF, 2021), while Uganda has roughly 50,000 children and young people living in 800 residential care facilities (Ddumba-Nyanzi et al., 2020). According to Ghana’s Children’s Act (Act 560) and Uganda’s Children’s Act (Chapter 59), children’s stay in care is for a maximum of 3 years or until they are 18 years, whichever is shorter. Care leavers in both nations struggle with independent living (e.g., employment, housing, education, and stigma) because there are no legislative aftercare programs and substantial informal social support (Bukuluki et al., 2019; Frimpong-Manso, 2018).

Both countries have relatively similar policies and institutional frameworks relating to vulnerable children and youth in care. One of the residential facilities for children in both countries is SOS Children's Villages (SOS CV), a non-profit organization that helps children without parental care. The SOS care system revolves around children’s villages that have several family houses (8–15) on a large compound (Willi et al., 2020). Each family house has 6–8 children who live as siblings under the care of a professional caregiver called a house-mother. Unlike all the other residential institutions, SOS CV has single-sex youth residences where children aged 14 and up go for a 4-year term to prepare for independent living. The youth residences are supervised by paid adults known as youth leaders. Also, young people in tertiary or vocational training can access semi-independent living support, a form of transitional support provided by SOS CV, for a further 3 years before transitioning into the wider community, which include a rented accommodation in the community or financial assistance if living with a biological relative and a monthly stipend (Willi et al., 2020).

Methodology

Study Sample

We used a qualitative design to study the experiences of early motherhood among care leavers in Ghana and Uganda. The study was done with young people who had left SOS Children’s Villages in Ghana and Uganda to live independently. We chose the participants using a purposeful sampling strategy. Inclusion criteria for the study included the young adult being a resident of the SOS CV for at least two years, being pregnant or having a child before leaving the organization, and being a parent for at least two years. SOS CV provided us with the contact information for 25 youth, 16 from Ghana and nine from Uganda, who fit the selection criterion, which was used to assist us in recruiting participants. Subsequently, the researchers contacted the participants to request their participation in the study. If the young person accepted to participate, we set up an interview at a time that was convenient for both parties.

Out of the 25 young women referred for the study, only four participated. Thirteen of them declined to participate in the study, and eight were unable to be reached. For this reason, we employed the snowball technique by asking the four young mothers we interviewed to pass on information about the research to other young mothers who met the inclusion criteria. In all, 10 young mothers took part in the interviews, five from each country (see Table 1). The six young women who joined the study, via the snowball method, matched the inclusion criteria and were linked with SOS CV, but were not on the original referral list because the institution did not have their contact information. The average age at the time participants gave birth to their first child was 18 years old. Most participants were married or living together with a partner, and the average number of children they had at the time of the study was two.

Ethics

The Ghanaian Department of Social Welfare and the Ministry of Gender, Labor, and Social Development in Uganda, the institutions responsible for out-of-home care for children, reviewed and approved the interview guide and study protocol. The SOS CVs in Ghana and Uganda gave permission to conduct the study. The SOS CVs in Ghana and Uganda gave permission to conduct the study. For the two in-person interviews, we complied with the COVID-19 safety protocols by doing the interviews in an open area and putting on face masks. We also used hand sanitizers and maintained social distancing. Before each interview, we made sure that the participants gave verbal or written consent after we had informed them about their rights to end the interview any time they wanted and not disclose information they felt uncomfortable divulging. We informed the participants that after transcribing the taped interviews, we would delete them to safeguard their privacy. To safeguard the confidentiality of the participants, we removed information that could show their identities and replaced their names with pseudonyms. Also, we did not disclose participants’ narrations to the SOS CV or any other third parties, except for the published work.

Data Collection and Analysis

We collected the data for the study in April 2021 through semi-structured interviews with the help of a guide created from the literature and the study’s objectives (Bryman, 2016). We piloted the guide on two young mothers to see if the questions were appropriate. The questions on the guide included: how did you get pregnant, what difficulties did you have during your pregnancy, and after the delivery of your child, and how did you handle the difficulties you faced during and after your pregnancy? We conducted the interviews in English, which was the language chosen by all the participants, and they lasted about 30 min on average. Except for one Zoom interview and two in-person interviews, most of the interviews were conducted through telephone calls. We used Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six steps for conducting a thematic analysis of interviews: familiarizing with the data sets, identifying initial codes, looking for themes, reviewing themes, defining themes, and reporting the findings. The analysis began with a verbatim transcription of the audio-recorded interviews. All the authors analyzed the transcripts to make sense of the meanings within the participants’ stories and code the common themes that emerged. The overall meanings that address the study objectives were discovered by analyzing the codes and keywords to establish initial themes (factors contributing to early pregnancy, challenges, and coping mechanisms) and sub-themes (e.g., inadequate SRH knowledge, lax supervision, and emotional stress and physical abuse). We employed peer debriefing to strengthen the findings. The authors gathered to assess the themes that emerged from the initial analysis of the interviews undertaken by two of the authors. This process was to ensure their analysis mirrored the participants’ perspectives. Also, the first and second authors had done some work with SOS in another study. As such we reflected on this issue to ensure it did not affect the decisions made in the current study (Finlay, 1998).

Findings

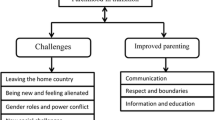

Two key factors that contributed to early pregnancy among the participants were their lack of understanding of SRH and caregivers’ poor oversight. The young mothers also experience financial and career difficulties, as well as emotional stress, physical abuse, and stigma. The participants used their inner determination and faith in the supernatural to overcome their obstacles.

Factors Contributing to Pregnancy

The analysis of the interviews revealed two factors accounted for the early and unplanned pregnancies experienced by the young mothers in the study: inadequate knowledge about SRH and limited supervision.

Inadequate Knowledge About SRH

All the participants stated that their first pregnancy was unexpected because they were not ready or in a position to deal with the responsibilities of parenting a child. According to most of them, these unintended births occurred because of their inadequate knowledge of SRH. The Ghanaian mothers reported receiving SRH information in school but not in their care facility. Their Ugandan counterparts reported having received SRH information at school and in the care facility. However, the participants stated that the information they received was superficial and thought it omitted crucial features, such as how to handle intimate relationships. This made it difficult for them to apply the knowledge in real-life circumstances. Cathy (Uganda) mentioned that the focus of sex education did not cover issues about sexual relationships “Things relating to relationships, no. They didn’t talk about that”. Another participant said:

I recall learning about SRH in school, but I still did not understand how someone could prevent a pregnancy when they had sex. We were not really told anything about these things in SOS. When I had my period, I do not recall anyone talking to me about such things (Sheila, Ghana).

From their accounts, many of the young mothers wanted to avoid early pregnancies, but their inadequate knowledge of SRH and naivety made it difficult for them to do so. For example, some of them described how they assumed they would not become pregnant after the first sexual encounter:

I asked him [partner] if I would not become pregnant. He said he removed the sperms, and I saw some sperms on the bed. I thought I would not get pregnant. It was only when I went back to school and became sick that the doctor confirmed I was three months gone (Vera, Ghana).

I had completed menstruation a few days earlier. So, I thought since I had completed my menstruation, I would not get pregnant. I had intercourse with the father of my son, and that is how I became pregnant. They [caregivers] counseled us, but they did not tell us how we could get pregnant (Mary, Uganda).

The comments from the participants showed how the lack of adequate information about SRH from the adults in their lives resulted in the participants making erroneous decisions, leading to several unwanted pregnancies.

Limited Supervision

Some participants also suggested that they became pregnant after leaving the children’s village and moving into semi-independent accommodation, which was either in a rented apartment or with their families. From their narratives, the transition to semi-independent living resulted in minimal supervision from an adult, which made them susceptible to unplanned pregnancies. For example, one participant blamed her pregnancy for her reunification with her biological mother, who neglected her because of the problems she was experiencing:

There was a problem, so they [SOS] asked me to go back to my mum. My mum was drinking a lot. One day, she got drunk and sent me out of her home. So, I went to live with my boyfriend, and that is how I got pregnant the first time (Bella, Uganda).

For another participant, the reason for entering care in the first place was because her mother had mental illness and her father was absent. Therefore, leaving care to live with her mentally ill mother, who could not properly guide her, led her to associate with bad company and her subsequent pregnancy. She said:

My mum was sick before I even went to the children’s village. I became a wayward child after going back home. Nobody paid attention to me; I was just following friends. That was how I got pregnant (Vivian, Ghana).

According to the participants, monitoring in semi-independent living and family reunification is insufficient. This reveals flaws in the techniques used to evaluate the suitability of the settings into which young women transition as they leave SOS CVs, resulting in a failure to recognize and manage the dangers to the young women's SRH.

Challenges

The participants experienced emotional stress and physical abuse, financial and employment challenges, and also stigma and discrimination.

Emotional Stress and Physical Abuse

Almost all the participants reported concealing their pregnancy because they feared eviction from the SOS CV, since it breached the organization's rules. For several of them, the burden of keeping the pregnancy a secret from their caregivers so that they would still enjoy SOS’s support was stressful. For instance, Sandra said “every day I wished that they [care facility] would find out about the pregnancy. When the aunt [caregiver] came to know about it, it relieved my heart”. Hiding the pregnancy meant that the young women went through the early stages of their pregnancy without support or medical help:

I found it difficult to inform them [care facility] when I realized I was pregnant because they did not expect that from me. It got me scared because I knew I would get sacked. So, I couldn’t tell anyone about it. Most of the things I went through during my pregnancy, I went through it alone (Vera, Ghana).

I was worried when I found out I was pregnant since we used to get lectures. They would educate and inform us on a variety of topics. They'd talk about the ‘emergency door.’ If you made a mistake, for example, you would depart through the emergency door. Because of my pregnancy, I was one person that left SOS via the emergency door (Priscilla, Uganda).

When the facility learned of the participants’ pregnancy, they sent them back to their families, which confirmed their worries about eviction. For several of the young mothers, the stress of being kicked out of care increased due to their partner’s reluctance to take responsibility for the pregnancy, support them, or the pressure to have an abortion:

… I remember when Aunt [name of social worker] came to the hospital, she asked me what I was doing there because I was in an antenatal ward. It was then that the doctor told her I was trying to abort my pregnancy at home and nearly died (Bella, Uganda).

Some participants who refused to abort their pregnancies reported their partners mistreated and abused them. Sandra mentioned “Whenever I would come back home late from work, he [partner] would beat me, he would become aggressive, so I got tired of being beaten and I rented my place”. The abuse some of the young mothers experienced made them develop suicidal ideas. Mary said “After my boyfriend got to know I was pregnant, he started treating me in a way that I wished I could even kill myself” (Mary, Uganda). Others, like Alice, had suicidal feelings because of being made to feel unfit as a mother in the community due to her early pregnancy:

Everybody made me feel like I was a small girl and I had become a mother and it was wrong. So, I was like, I should just kill myself and leave this world.

Instead of receiving support after becoming pregnant and parents, the young mothers faced neglect and eviction from the care facility, emotional and physical assault from their partners, and moral judgment from the community, which put several of the participants through emotional stress.

Financial and Employment Challenges

All participants who had jobs at the time of this study worked in low-paying jobs such as shop attendant. In certain situations, the young mothers could not work because they had to stay at home to cater to their children as they lacked the resources to get childcare services or informal caregiving support:

I didn't have enough time to take care of my children. My husband started complaining that I didn't return from work early to take care of the children. My husband and I decided I would quit the job and do my own small business. It’s really not very profitable, but I have time to take care of the children (Vivian, Ghana).

For the Ugandan participants, the care facility provided minimal support before and a few months after childbirth, but the Ghanaian participants received no support, which had several implications for the mothers and their children:

Since my baby was not breastfeeding, I had to get tinned food like tinned milk and baby food. They were expensive and getting someone with cattle to give you milk was difficult, given I was in an urban setting. I ended up feeding my baby with cassava flour. Whatever I ate, that is what she [baby] also ate. I even reserved some leftover food for her (Bella, Uganda).

Since most of the young mothers had weak social support, were orphans or from low-income families, losing support from the care facility and their partners resulted in financial difficulties. Moreover, they were helpless because they could not trade off childcare responsibilities while going out to work.

Stigma and Discrimination

Participants mentioned that friends and colleagues stigmatized them at school and in the community because of their pregnancy. Bella described becoming pregnant early as a curse, “I lost friends; I lost my brothers. It was a curse if you got pregnant early. People talk about you, you become a terrible example. People ignore you; your friends hate you”. Some young mothers dropped out or changed schools because of perceived and real stigma which had a negative effect on their self-esteem and confidence “… I was the first girl to get pregnant. (…) and some of my friends started discriminating against me. They talked about me behind my back. That is how I stopped school” (Cathy, Uganda).

Coping Mechanism

Even though participants recounted experiencing difficult life moments after becoming mothers, their narrations also reveal how they coped through positive drive and faith. Coping did not completely resolve their hardships, but it provided some respite for the young mothers.

Positive Drive

The participants’ optimistic attitude motivated them to address their issues. They were motivated by a desire to succeed, a strong work ethic, and a bright future perspective. They made the mental transition from relying on others to becoming self-sufficient. “It is getting determination in yourself,” Mary said when asked what she required to deal with her problems. Cathy said it was her fighting attitude, saying, “As a person, one of my assets is that I am a fighter.” When asked how they managed life after leaving care and lost support from the institution, participants emphasized their dedication to achieving their goals:

I had this thing in mind. For me, I know working for myself is the only way I can get money. So, I despise no job. I do every type of work you can think of apart from prostitution. That is how I get money to buy for my boy and myself, and pay my rent (Mary, Uganda).

I used to struggle and see that I make some small money. Yeah, I was doing some work. You know the guy [partner] ran away; so, I had to find ways of how I live like anybody (Bella, Uganda).

The young mothers based their motivation on the expectation that things will improve in the future:

I knew the situation wouldn't stay the same. It was difficult back then, but I knew things would change for the better (Cathy, Uganda).

The hope for a better tomorrow complemented the participants’ determination and hard work.

Faith

The faith of the young mothers played out in their recollections about how they overcame their challenges. Thus, beyond their abilities and personal drive, the participants depended on the belief in the existence and power to intervene and change the course of their difficult lives. Also, the young mothers mentioned the involvement in faith-based activities like praying as being helpful to them in handling their issues. Stigmatized by schoolmates and other people in the community, participating in religious activities made Priscilla achieve inclusion among her peers who were not pregnant or parents. Thus, the shared identity of faith and religion trumped the identity of motherhood. It also helped her avoid overthinking about her situation.

I didn’t want to worry about my problems too much, so when I went to church, I kept myself occupied with church events and other church members. We pray and fast as members of the [name of church]. These were the things that helped me stay motivated and strong (Priscilla, Uganda).

Referring to early pregnancy as a hindrance to benefiting from a scholarship opportunity, Vivian narrated how she coped:

I didn’t feel bad about the opportunity I missed due to my pregnancy. Because if it’s still God’s desire for me to get one, I will. That’s how I felt, that maybe it will come, and it might even come in a better way (Vivian, Ghana).

Vivian's faith in the supernatural urged her to not be disappointed by the missed opportunity, but to keep her hopes alive for another. As a result, the participants' faith provided them with a purpose to keep pushing on.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to look into the experiences of pregnant and parenting young mothers who had been in residential care in Ghana and Uganda. Limited SRH knowledge and lax monitoring during the semi-independent phase of leaving care were the risk factors for early pregnancy. The participants’ report of not receiving adequate information and guidance on SRH, including sex education, which partly explained their early pregnancy and childbirth, is a conclusion consistent with earlier research studies (Albertson et al., 2020; Boustani et al., 2015; Harmon-Darrow et al., 2020; Nixon et al., 2019;). According to research on residential care in Ghana and Uganda, the child-to-caregiver ratio is high, and most caregivers in the facilities are untrained (Frimpong-Manso, 2021; Walakira et al., 2015). As a result, it is probable that time limits and restricted capabilities made it impossible for the adults to supply SRH information the young people needed.

There are policies in place in nations like the United States and the United Kingdom that allow young people to remain in care past the legal age of leaving care (Strahl et al., 2020). These policies aim to enhance the outcomes of young people in care by making their transition to adulthood comparable to those of their counterparts who are not in out-of-home care. Most research from the United States suggests a link between being in extended care and decreased rates of early childbirth (Combs et al., 2018; Dworsky & Courtney, 2010; Oshima et al., 2013), contrary to the findings made in this study. The young women in this study could not take advantage of the extended care in preventing unplanned pregnancy because of a lack of supervision by an adult working in their residential facility, a reason cited in the literature as leading to risky sexual conduct among young people in residential care (Maxwell & Chase, 2008). As a result, throughout this transitional period, social workers and other staff should assess young people's needs to determine what advice and help they require.

Care leavers in Africa (Frimpong-Manso, 2018; Pryce et al., 2015; Sekibo, 2019; van Breda & Frimpong-Manso, 2020) encounter many problems (e.g., stigma, employment challenges, and abuse) during their transition to adulthood, similar to the challenges that the young women in our research experienced. This study adds to the existing literature by pointing out the additional layer of vulnerability confronting this subgroup of care leavers (young mothers). For example, an interesting finding of the study was that a key factor that contributed to the difficulties experienced by the young mothers was their eviction from care for getting pregnant. Because of the eviction, the young people’s transition from care was sudden, unplanned, and involved the withdrawal of support by the care facility. These findings affirm the literature from other developing countries (e.g., Islam, 2013) which have shown that young people evicted from care have the most challenging transition to adulthood as they suffer a range of hardships after leaving care. Aside from the lack of institutional help, the young women have limited informal help because they frequently return to their original families, many of whom still have pre-existing difficulties such as poverty and mental health concerns. SOS CV hopes to provide the young people in its care with a transition to adulthood that is comparable to that of their counterparts who are not in care by extending care through semi-independent living. Evicting them defeats this purpose, pointing out the necessity for a care facility to enforce procedures to support young people avoid unwanted pregnancies.

Another challenge that the young mothers faced was being in partnerships with men who were negligent in caring for their children and abusive, resulting in emotional and financial problems for them. This finding adds to the limited evidence that care leavers may be vulnerable to abusive partners (Purtell et al., 2020), which indicates the need to develop measures to assist young people in care develop healthy intimate relationships.

The young mothers’ coping strategies reflect their perseverance and resilience in the face of adversity. Many of them continued their education or learned a trade while working to care for their children. The strategies they employed sprang from their inner worlds (personal motivation and faith) and the associated informal support from their involvement in church activities, often fueled by the desire to do well for their children and meet their emotional and material needs. Other research has found that care leavers use comparable coping strategies to those used by the young mothers in this study (Frimpong-Manso, 2018; Häggman-Laitila et al., 2019). The coping techniques of the participants indicate a lack of material resources such as financial resources, particularly from formal sources, which is a crucial resource used by care leavers to cope with their difficulties (Frimpong-Manso, 2018; Häggman-Laitila et al., 2019). While inner strengths are helpful, there is evidence that addressing specific needs (e.g., financial and psychosocial services), which are critical to young mothers’ ability to cope with their challenges, necessitates institutional support (Frimpong-Manso, 2015; Mhongera, & Lombard, 2016).

Limitations of the Study

The study contributes to the African literature on pregnancy and parenting among young women with an out-of-home care experience. However, the study has some flaws. It was hard to reach the young mothers, particularly because of the COVID-19, and the snowballing strategy did not work well, resulting in a smaller sample size than the authors had expected. Another drawback is that SOS CV is one private residential care facility that follows a specific care model and may not represent the whole range of models utilized by other providers of residential care as discussed under the rationale of the study. It is possible that bringing in participants from other institutions might have influenced the study’s outcome. The applicability of the findings to other contexts is also limited because the care facility investigated has some interventions that might not be available in other settings, and the living situations of the young mothers interviewed may differ from other care leavers. Also, it may also be possible that some youth who refused to participate in this study did so due to possible experiences of stigma.

Implications of the Study

Despite the study’s limitations, findings of the study have implications for pregnant and parenting youth in Ghana and Uganda leaving residential care, and other developing nations with similar socio-economic conditions and residential and foster care systems. Given the inadequacies in the young people’s knowledge and ability to apply SRH, as well as the importance of this information for preventing unwanted pregnancies, residential facilities such as SOS CV should have a specified person (e.g., social worker) with the training and skills to provide such information to young people in care. Besides, there can be the development of a context specific curriculum that will be used in providing SRH knowledge to the young people. Ideally, the curriculum should be co-produced with the young people as this will help capture aspects of SRH that are important to them. Also, young mothers can be trained as peer educators to share their experiences with other girls in care with the hope of preventing early pregnancy. Multi-sectoral coordination between different agencies (e.g., Department of Social Welfare and NGOs) is required to ensure that young women have access to psychosocial support to help them cope with the negative effects of stigma and prejudice, as well as suicidal ideations. Social workers in the residential care facilities should also ensure that young people in transitional housing during the semi-independent phase of leaving care get adequate supervision and monitoring to help them make informed and positive decisions around sexual health and relationships.

The findings highlight the negative impact of evicting pregnant and parenting youth from residential care. To address the concerns that the institution has, such as the young mothers negatively influencing the other children and young people, they can have separate accommodation for the young mothers during and after childbirth. Governments in Ghana and Uganda should consider social inclusion programs that will aid the smooth reintegration of care leavers, including pregnant and parenting young girls back into their communities. This program, facilitated by social workers, should offer a variety of supports for the young people’s educational, career, and parenting abilities. Implications for research emanating from this study include the need to explore the experiences of young fathers in out-of-home care, and the experiences of the caregivers and other staff in residential care in relation to their work with pregnant and parenting young people. It will also be fascinating to investigate the sexual and reproductive health knowledge and behavior of children and young people in low-income countries who are in out-of-home care.

References

Ahrens, K., McCarthy, C., Simoni, J., Dworksy, A., & Courtney, M. (2013). Psychosocial pathways to sexually transmitted infection risk among youth transitioning out of foster care: Evidence from a longitudinal cohort study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53, 478–485.

Albertson, K., Crouch, J. M., Udell, W., Schimmel-Bristow, A., Serrano, J., & Ahrens, K. R. (2020). Caregiver-endorsed strategies to improving sexual health outcomes among foster youth. Child & Family Social Work, 25(3), 557–567. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12726

Aparicio, E., Pecukonis, E. V., & O’Neale, S. (2015). “The love that I was missing”: Exploring the lived experience of motherhood among teen mothers in foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 51, 44–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.02.002

Bermea, A., Forenza, B., Rueda, H., & Toews, M. (2018). Resiliency and adolescent motherhood in the context of residential foster care. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 36(5), 459–470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-018-0574-0

Botchway, S. K., Quigley, M. A., & Gray, R. (2014). Pregnancy-associated outcomes in women who spent some of their childhood looked after by local authorities: Findings from the UK Millennium Cohort Study. British Medical Journal Open, 4(12), e005468. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005468

Boustani, M. M., Frazier, S. L., Hartley, C., Meinzer, M., & Hedemann, E. (2015). Perceived benefits and proposed solutions for teen pregnancy: Qualitative interviews with youth care workers. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 85(1), 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000040

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods (5th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Bukuluki, P., Kamya, S., Kasirye, R., & Nabulya, A. (2019). Facilitating the transition of adolescents and emerging adults from care into employment in Kampala, Uganda: A case study of Uganda Youth Development Link. Emerging Adulthood, 8(1), 35–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696819833592

Coler, L. (2018). “I need my children to know that I will always be here for them”: Young care leavers’ experiences with their own motherhood in Buenos Aires, Argentina. SAGE Open, 8(4), 215824401881991. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244018819911

Combs, K. M., Begun, S., Rinehart, D. J., & Taussig, H. (2018). Pregnancy and childbearing among young adults who experienced foster care. Child Maltreatment, 23(2), 166–174. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559517733816

Datta, J., Macdonald, G., Barlow, J., Barnes, J., & Elbourne, D. (2017). Challenges faced by young mothers with a care history and views of stakeholders about the potential for group family nurse partnership to support their needs. Children & Society, 31(6), 463–474. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12233

Ddumba-Nyanzi, I., Fricke, M., Max, A. H., Nambooze, M., & Riley, M. (2020). The care leaver experience: A report on children and young people’s experiences in and after leaving residential care in Uganda. Retrieved from https://www.uganda-care-leavers.org/blog/uclreport2019

Dworsky, A., & Courtney, M. (2010). The risk of teenage pregnancy among transitioning foster youth: Implications for extending state care beyond age 18. Children and Youth Services Review, 32(10), 1351–1356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.06.002

Eastman, A. L., Palmer, L., & Ahn, E. (2019). Pregnant and parenting youth in care and their children: A literature review. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 36(6), 571–581. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-019-00598-8

Finlay, L. (1998). Reflexivity: An essential component for all research?. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 61(10), 453–456. https://doi.org/10.1177/030802269806101005

Font, S. A., Cancian, M., & Berger, L. M. (2019). Prevalence and risk factors for early motherhood among low-income, maltreated, and foster youth. Demography, 56(1), 261–284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-018-0744-x

Frimpong-Manso, K. (2012). Preparation for young people leaving care: The case of SOS Children’s Village, Ghana. Child Care in Practice, 18(4), 341–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/13575279.2012.713850

Frimpong-Manso, K. (2015). The social support networks of care leavers from a children’s village in Ghana: Formal and informal supports. Child & Family Social Work, 22(1), 195–202. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12218

Frimpong-Manso, K. (2018). Building and utilizing resilience: The challenges and coping mechanisms of care leavers in Ghana. Children and Youth Services Review, 87, 52–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.02.016

Frimpong-Manso, K. (2021). Funding orphanages on donations and gifts: Implications for orphans in Ghana. New Ideas in Psychology, 60, 100835. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.newideapsych.2020.100835

Ghana Department of Social Welfare and the United Nations Children’s Fund [UNICEF]. (2021). Children living in residential care in Ghana: Findings from a survey of wellbeing. UNICEF.

Häggman-Laitila, A., Salokekkilä, P., & Karki, S. (2019). Young people’s preparedness for adult life and coping after foster care: A systematic review of perceptions and experiences in the transition period. Child & Youth Care Forum, 48(5), 633–661. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-019-09499-4

Harmon-Darrow, C., Burruss, K., & Finigan-Carr, N. (2020). “We are kind of their parents”: Child welfare workers’ perspective on sexuality education for foster youth. Children and Youth Services Review, 108, 104565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104565

Islam, T. (2013). Residential childcare: The experiences of young people in Bangladesh (Publication No. U609188) [Unpublished doctoral dissertation, The University of Edinburgh]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

King, B., & Van Wert, M. (2017). Predictors of early childbirth among female adolescents in foster care. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(2), 226–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.02.014

Kingston, D., Heaman, M., Fell, D., & Chalmers, B. (2012). Comparison of adolescent, young adult, and adult women’s maternity experiences and practices. Pediatrics, 129(5), e1228. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-1447

Maxwell, C., & Chase, E. (2008). Peer pressure: Beyond rhetoric to reality. Sex Education: Sexuality, Society and Learning, 8(3), 303–314.

Mhongera, P., & Lombard, A. (2016). Who is there for me? Evaluating the social support received by adolescent girls transitioning from institutional care in Zimbabwe. Practice, 29(1), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/09503153.2016.1185515

Nixon, C., Elliott, L., & Henderson, M. (2019). Providing sex and relationships education for looked-after children: A qualitative exploration of how personal and institutional factors promote or limit the experience of role ambiguity, conflict and overload among caregivers. British Medical Journal Open, 9(4), e025075. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025075

Oshima, K. M. M., Narendorf, S., & McMillen, J. (2013). Pregnancy risk among older youth transitioning out of foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 35(10), 1760–1765. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.08.001

Pryce, J., Jones, S., Wildman, A., Thomas, A., Okrzesik, K., & Kaufka-Walts, K. (2015). Aging out of care in Ethiopia: Challenges and implications facing orphans and vulnerable youth. Emerging Adulthood, 4(2), 119–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696815599095

Purtell, J., Mendes, P., & Saunders, B. J. (2020). Care leavers, ambiguous loss and early parenting: Explaining high rates of pregnancy and parenting amongst young people transitioning from out-of-home care. Children Australia, 45(4), 241–248. https://doi.org/10.1017/cha.2020.58

Putnam-Hornstein, E., Hammond, I., Eastman, A. L., McCroskey, J., & Webster, D. (2016). Extended foster care for transition-age youth: An opportunity for pregnancy prevention and parenting support. Journal of Adolescent Health, 58(4), 485–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.11.015

Radey, M., Schelbe, L., McWey, L. M., Holtrop, K., & Canto, A. I. (2016). “It’s really overwhelming”: Parent and service provider perspectives of parents aging out of foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 67, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.05.013

Roberts, L., Maxwell, N., & Elliott, M. (2019). When young people in and leaving state care become parents: What happens and why? Children and Youth Services Review, 104, 104387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104387

Roberts, L., Meakings, S., Forrester, D., Smith, A., & Shelton, K. (2017). Care-leavers and their children placed for adoption. Children and Youth Services Review, 79, 355–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.06.030

Rouse, H. L., Hurt, T. R., Melby, J. N., Bartel, M., McCurdy, B., McKnight, E., Zhao, F., Behrer, C., & Weems, C. F. (2021). Pregnancy and parenting among youth transitioning from foster care: A mixed methods study. Child & Youth Care Forum, 50(1), 167–197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-020-09567-0

Schelbe, L., & Geiger, J. M. (2017). Parenting under pressure: Experiences of parenting while aging out of foster care. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 34(1), 51–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-016-0472-2

Sekibo, B. (2019). Experiences of young people early in the transition from residential care in Lagos State, Nigeria. Emerging Adulthood, 8(1), 92–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696818822232

Shpiegel, S., Fleming, T., Mishraky, L., VanWert, S., Goetz, B., Aparicio, E. M., & King, B. (2021). Factors associated with first and repeat births among females emancipating from foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 125, 105977. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2021.105977

Strahl, B., van Breda, A., Mann-Feder, V., & Schröer, W. (2020). A multinational comparison of care-leaving policy and legislation. Journal of International and Comparative Social Policy, 37(1), 34–49. https://doi.org/10.1017/ics.2020.26

UNFPA (2021). Factsheet on teenage pregnancy 2021. Retrieved from https://uganda.unfpa.org/en/publications/fact-sheet-teenage-pregnancy-2021-0

UNICEF. (2019). Early child bearing. Retrieved from https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-health/adolescent-health/

van Breda, A., & Frimpong-Manso, K. (2020). Leaving care in Africa. Emerging Adulthood, 8(1), 3–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696819895398

Walakira, E. J., Dumba-Nyanzi, I., & Bukenya B. (2015). Child care institutions in selected districts in Uganda and the situation of children in care: A baseline survey report for the strong beginnings project. Terres des Hommes Netherlands.

Willi, R., Reed, D., & Houedenou, G. (2020). An evaluation methodology for measuring the long-term impact of family strengthening and alternative child care services: The case of SOS children’s villages. International Journal of Child, Youth and Family Studies, 11(4), 7–28. https://doi.org/10.18357/ijcyfs114202019936

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Frimpong-Manso, K., Bukuluki, P., Addy, T.N.A. et al. Pregnancy and Parenting Experiences of Care-Experienced Youth in Ghana and Uganda. Child Adolesc Soc Work J 39, 683–692 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-022-00829-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-022-00829-5