Abstract

Purpose

Farnesol is a key metabolite of the mevalonate pathway and known as an antioxidant. We examined whether farnesol treatment protects the ischemic heart.

Methods

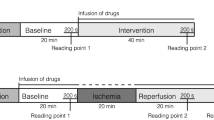

Male Wistar rats were treated orally with 0.2, 1, 5, and 50 mg/kg/day farnesol/vehicle for 12 days, respectively. On day 13, the effect of farnesol treatment on cardiac ischemic tolerance and biochemical changes was tested. Therefore, hearts were isolated and subjected either to 30 min coronary occlusion followed by 120 min reperfusion to measure infarct size or to 10 min aerobic perfusion to measure cardiac mevalonate pathway end-products (protein prenylation, cholesterol, coenzyme Q9, coenzyme Q10, dolichol), and 3-nitrotyrosine (oxidative/nitrosative stress marker), respectively. The cytoprotective effect of farnesol was also tested in cardiomyocytes subjected to simulated ischemia/reperfusion.

Results

Farnesol pretreatment decreased infarct size in a U-shaped dose–response manner where 1 mg/kg/day dose reached a statistically significant reduction (22.3 ± 3.9 % vs. 40.9 ± 6.1 % of the area at risk, p < 0.05). Farnesol showed a similar cytoprotection in cardiomyocytes. The cardioprotective dose of farnesol (1 mg/kg/day) significantly increased the marker of protein geranylgeranylation, but did not influence protein farnesylation, cardiac tissue cholesterol, coenzyme Q9, coenzyme Q10, and dolichol. While the cardioprotective dose of farnesol did not influence 3-nitrotyrosine, the highest dose of farnesol (50 mg/kg/day) tested did not show cardioprotection, however, it significantly decreased cardiac 3-nitrotyrosine.

Conclusions

This is the first demonstration that oral farnesol treatment reduces infarct size. The cardioprotective effect of farnesol likely involves increased protein geranylgeranylation and seems to be independent of the antioxidant effect of farnesol.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ferdinandy P, Schulz R, Baxter GF. Interaction of cardiovascular risk factors with myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury, preconditioning, and postconditioning. Pharmacol Rev. 2007;59:418–58.

Ferdinandy P, Csonka C, Csont T, Szilvassy Z, Dux L. Rapid pacing-induced preconditioning is recaptured by farnesol treatment in hearts of cholesterol-fed rats: role of polyprenyl derivatives and nitric oxide. Mol Cell Biochem. 1998;186:27–34.

Qamar W, Sultana S. Farnesol ameliorates massive inflammation, oxidative stress and lung injury induced by intratracheal instillation of cigarette smoke extract in rats: an initial step in lung chemoprevention. Chem Biol Interact. 2008;176:79–87.

Jahangir T, Khan TH, Prasad L, Sultana S. Farnesol prevents Fe-NTA-mediated renal oxidative stress and early tumour promotion markers in rats. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2006;25:235–42.

Khan R, Sultana S. Farnesol attenuates 1,2-dimethylhydrazine induced oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptotic responses in the colon of Wistar rats. Chem Biol Interact. 2011;192:193–200.

Crick DC, Andres DA, Waechter CJ. Farnesol is utilized for protein isoprenylation and the biosynthesis of cholesterol in mammalian cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;211:590–9.

Goldstein JL, Brown MS. Regulation of the mevalonate pathway. Nature. 1990;343:425–30.

Resh MD. Trafficking and signaling by fatty-acylated and prenylated proteins. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:584–90.

Leung KF, Baron R, Seabra MC. Thematic review series: lipid posttranslational modifications. geranylgeranylation of Rab GTPases. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:467–75.

Reddy S, Comai L. Lamin A, farnesylation and aging. Exp Cell Res. 2012;318:1–7.

Takemoto M, Liao JK. Pleiotropic effects of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme a reductase inhibitors. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:1712–9.

Aberg F, Appelkvist EL, Dallner G, Ernster L. Distribution and redox state of ubiquinones in rat and human tissues. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1992;295:230–4.

Greenberg S, Frishman WH. Co-enzyme Q10: a new drug for cardiovascular disease. J Clin Pharmacol. 1990;30:596–608.

Hano O, Thompson-Gorman SL, Zweier JL, Lakatta EG. Coenzyme Q10 enhances cardiac functional and metabolic recovery and reduces Ca2+overload during postischemic reperfusion. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:2174–81.

Doucey MA, Hess D, Cacan R, Hofsteenge J. Protein C-mannosylation is enzyme-catalysed and uses dolichyl-phosphate-mannose as a precursor. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:291–300.

Takeda J, Kinoshita T. GPI-anchor biosynthesis. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:367–71.

Kornfeld R, Kornfeld S. Assembly of asparagine-linked oligosaccharides. Annu Rev Biochem. 1985;54:631–64.

Ferdinandy P, Schulz R. Nitric oxide, superoxide, and peroxynitrite in myocardial ischaemia-reperfusion injury and preconditioning. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;138:532–43.

Yasmin W, Strynadka KD, Schulz R. Generation of peroxynitrite contributes to ischemia-reperfusion injury in isolated rat hearts. Cardiovasc Res. 1997;33:422–32.

Kocsis GF, Pipis J, Fekete V, et al. Lovastatin interferes with the infarct size-limiting effect of ischemic preconditioning and postconditioning in rat hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:2406–9.

Csonka C, Kupai K, Kocsis GF, et al. Measurement of myocardial infarct size in preclinical studies. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2010;61:163–70.

Epstein WW, Lever D, Leining LM, Bruenger E, Rilling HC. Quantitation of prenylcysteines by a selective cleavage reaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:9668–70.

Rousseau G, Varin F. Determination of ubiquinone-9 and 10 levels in rat tissues and blood by high-performance liquid chromatography with ultraviolet detection. J Chromatogr Sci. 1998;36:247–52.

Dini B, Dolfi C, Santucci V, et al. Effects of ageing and increased haemolysis on the levels of dolichol in rat spleen. Exp Gerontol. 2001;37:99–105.

Csont T, Gorbe A, Bereczki E, et al. Biglycan protects cardiomyocytes against hypoxia/reoxygenation injury: role of nitric oxide. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;48:649–52.

Li X, Heinzel FR, Boengler K, Schulz R, Heusch G. Role of connexin 43 in ischemic preconditioning does not involve intercellular communication through gap junctions. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2004;36:161–3.

Bentinger M, Grunler J, Peterson E, Swiezewska E, Dallner G. Phosphorylation of farnesol in rat liver microsomes: properties of farnesol kinase and farnesyl phosphate kinase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1998;353:191–8.

Ali BR, Nouvel I, Leung KF, Hume AN, Seabra MC. A novel statin-mediated “prenylation block-and-release” assay provides insight into the membrane targeting mechanisms of small GTPases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;397:34–41.

Lane KT, Beese LS. Thematic review series: lipid posttranslational modifications. Structural biology of protein farnesyltransferase and geranylgeranyltransferase type I. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:681–99.

Brar BK, Jonassen AK, Egorina EM, et al. Urocortin-II and urocortin-III are cardioprotective against ischemia reperfusion injury: an essential endogenous cardioprotective role for corticotropin releasing factor receptor type 2 in the murine heart. Endocrinology. 2004;145:24–35.

Xiang SY, Vanhoutte D, Del Re DP, et al. RhoA protects the mouse heart against ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:3269–76.

Dougherty CJ, Kubasiak LA, Frazier DP, et al. Mitochondrial signals initiate the activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) by hypoxia-reoxygenation. FASEB J. 2004;18:1060–70.

Matejikova J, Kucharska J, Pancza D, Ravingerova T. The effect of antioxidant treatment and NOS inhibition on the incidence of ischemia-induced arrhythmias in the diabetic rat heart. Physiol Res. 2008;57 Suppl 2:55–60.

Molyneux SL, Florkowski CM, Richards AM, Lever M, Young JM, George PM. Coenzyme Q10; an adjunctive therapy for congestive heart failure? N Z Med J. 2009;122:74–9.

Kapusta L, Zucker N, Frenckel G et al. From discrete dilated cardiomyopathy to successful cardiac transplantation in congenital disorders of glycosylation due to dolichol kinase deficiency (DK1-CDG). Heart Fail Rev. 2012;18:187-96

Lefeber DJ, de Brouwer AP, Morava E, et al. Autosomal recessive dilated cardiomyopathy due to DOLK mutations results from abnormal dystroglycan O-mannosylation. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002427.

Chagas CE, Vieira A, Ong TP, Moreno FS. Farnesol inhibits cell proliferation and induces apoptosis after partial hepatectomy in rats. Acta Cir Bras. 2009;24:377–82.

Joo JH, Liao G, Collins JB, Grissom SF, Jetten AM. Farnesol-induced apoptosis in human lung carcinoma cells is coupled to the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7929–36.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Innovation Office (5LET_STATIN_08, TAMOP-4.2.2-08/1/2008-0013, TAMOP-4.2.1/B-09/1/KONV-2010-0005, TÁMOP-4.2.2/B-10/1-2010-0012, and TAMOP-4.2.2/A-11/1/KONV-2012-0035) and a grant from the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund (OTKA PD 106001). A. Görbe and T. Csont hold a “János Bolyai Fellowship” from the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

C. Csonka and P. Ferdinandy contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Szűcs, G., Murlasits, Z., Török, S. et al. Cardioprotection by Farnesol: Role of the Mevalonate Pathway. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 27, 269–277 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10557-013-6460-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10557-013-6460-2