Abstract

Purpose

Chronic inflammation has been implicated in the etiology of various chronic diseases. We previously found that certain urinary isoflavones are associated with markers of inflammation. In the present study, we examined the associations of serum C-reactive protein (CRP) and white blood cell (WBC) count with lignans, which are more frequent in the Western diet than isoflavones.

Methods

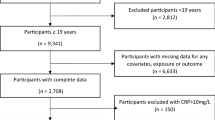

Our analysis included 2,028 participants of NHANES 2005–2008 and 2,628 participants of NHANES 1999–2004 aged 18 years and older. The exposures of interest were urinary mammalian lignans (enterodiol and enterolactone). Outcome variables were two inflammatory markers (CRP [≤10 mg/L] and WBC [≥3.0 and ≤11.7 (1,000 cells/μL)]). Log-transformed CRP concentration and WBC count by log-transformed creatinine-standardized concentrations of mammalian lignans were used for linear regression.

Results

Statistically significant inverse associations of urinary lignan, enterodiol, and enterolactone concentrations with circulating CRP and WBC counts were observed in the multivariate-adjusted models: In NHANES 2005–2008, per one-percent increase in lignan concentrations in the urine, CRP concentrations and WBC counts decreased by 8.1 % (95 % CI −11.5, −4.5) and 1.9 % (95 % CI −2.7; −1.2), respectively. Per one-percent increase in enterodiol and enterolactone, WBC counts decreased by 2.1 % (95 % CI −2.8, −1.3) and 1.3 % (95 % CI −1.9, −0.6), respectively. In NHANES 1999–2004, analogous results were 3.0 % (95 % CI −5.6, −0.3), 1.2 % (95 % CI −2.0; −0.4), 1.0 % (95 % CI −1.8, −0.2), and 0.8 % (95 % CI −1.4, 0.2).

Conclusions

Mammalian lignans were inversely associated with markers of chronic inflammation. Due to the cross-sectional design, our findings require confirmation in prospective studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Wu SH, Shu XO, Chow WH, Xiang YB, Zhang X, Li HL, Cai Q, Ji BT, Cai H, Rothman N, Gao YT, Zheng W, Yang G (2012) Soy food intake and circulating levels of inflammatory markers in Chinese women. J Acad Nutr Diet 112(7):996–1004. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2012.04.001

Touvier M, Fezeu L, Ahluwalia N, Julia C, Charnaux N, Sutton A, Mejean C, Latino-Martel P, Hercberg S, Galan P, Czernichow S (2013) Association between prediagnostic biomarkers of inflammation and endothelial function and cancer risk: a nested case-control study. Am J Epidemiol 177(1):3–13. doi:10.1093/aje/kws359

Kotani K, Sakane N (2012) White blood cells, neutrophils, and reactive oxygen metabolites among asymptomatic subjects. Int J Prev Med 3(6):428–431

Ridker PM, Hennekens CH, Buring JE, Rifai N (2000) C-reactive protein and other markers of inflammation in the prediction of cardiovascular disease in women. N Engl J Med 342(12):836–843. doi:10.1056/NEJM200003233421202

Iida M, Ikeda F, Ninomiya T, Yonemoto K, Doi Y, Hata J, Matsumoto T, Kiyohara Y (2012) White blood cell count and risk of gastric cancer incidence in a general Japanese population: the Hisayama study. Am J Epidemiol 175(6):504–510. doi:10.1093/aje/kwr345

Pepys MB, Hirschfield GM (2003) C-reactive protein: a critical update. J Clin Invest 111(12):1805–1812. doi:10.1172/JCI18921

Siemes C, Visser LE, Coebergh JW, Splinter TA, Witteman JC, Uitterlinden AG, Hofman A, Pols HA, Stricker BH (2006) C-reactive protein levels, variation in the C-reactive protein gene, and cancer risk: the Rotterdam Study. J Clin Oncol 24(33):5216–5222. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.07.1381

Saito K, Kihara K (2011) C-reactive protein as a biomarker for urological cancers. Nat Rev Urol 8(12):659–666. doi:10.1038/nrurol.2011.145

Bazzano LA, He J, Muntner P, Vupputuri S, Whelton PK (2003) Relationship between cigarette smoking and novel risk factors for cardiovascular disease in the United States. Ann Intern Med 138(11):891–897

Wener MH, Daum PR, McQuillan GM (2000) The influence of age, sex, and race on the upper reference limit of serum C-reactive protein concentration. J Rheumatol 27(10):2351–2359

Visser M, Bouter LM, McQuillan GM, Wener MH, Harris TB (1999) Elevated C-reactive protein levels in overweight and obese adults. JAMA 282(22):2131–2135

Imhof A, Froehlich M, Brenner H, Boeing H, Pepys MB, Koenig W (2001) Effect of alcohol consumption on systemic markers of inflammation. Lancet 357(9258):763–767. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04170-2

Yu Z, Ye X, Wang J, Qi Q, Franco OH, Rennie KL, Pan A, Li H, Liu Y, Hu FB, Lin X (2009) Associations of physical activity with inflammatory factors, adipocytokines, and metabolic syndrome in middle-aged and older chinese people. Circulation 119(23):2969–2977. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.833574

Nanri H, Nakamura K, Hara M, Higaki Y, Imaizumi T, Taguchi N, Sakamoto T, Horita M, Shinchi K, Tanaka K (2011) Association between dietary pattern and serum C-reactive protein in Japanese men and women. J Epidemiol 21(2):122–131

Zalokar JB, Richard JL, Claude JR (1981) Leukocyte count, smoking, and myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 304(8):465–468. doi:10.1056/NEJM198102193040806

Dixon JB, O’Brien PE (2006) Obesity and the white blood cell count: changes with sustained weight loss. Obes Surg 16(3):251–257. doi:10.1381/096089206776116453

Aminzadeh Z, Parsa E (2011) Relationship between age and peripheral white blood cell count in patients with sepsis. Int J Prev Med 2(4):238–242

Pitsavos C, Chrysohoou C, Panagiotakos DB, Skoumas J, Zeimbekis A, Kokkinos P, Stefanadis C, Toutouzas PK (2003) Association of leisure-time physical activity on inflammation markers (C-reactive protein, white cell blood count, serum amyloid A, and fibrinogen) in healthy subjects (from the ATTICA study). Am J Cardiol 91(3):368–370

Pradhan AD, Manson JE, Rossouw JE, Siscovick DS, Mouton CP, Rifai N, Wallace RB, Jackson RD, Pettinger MB, Ridker PM (2002) Inflammatory biomarkers, hormone replacement therapy, and incident coronary heart disease: prospective analysis from the Women’s Health Initiative observational study. JAMA 288(8):980–987

Yoneyama S, Miura K, Sasaki S, Yoshita K, Morikawa Y, Ishizaki M, Kido T, Naruse Y, Nakagawa H (2007) Dietary intake of fatty acids and serum C-reactive protein in Japanese. J Epidemiol 17(3):86–92

Ma Y, Griffith JA, Chasan-Taber L, Olendzki BC, Jackson E, Stanek EJ 3rd, Li W, Pagoto SL, Hafner AR, Ockene IS (2006) Association between dietary fiber and serum C-reactive protein. Am J Clin Nutr 83(4):760–766

Esmaillzadeh A, Kimiagar M, Mehrabi Y, Azadbakht L, Hu FB, Willett WC (2006) Fruit and vegetable intakes, C-reactive protein, and the metabolic syndrome. Am J Clin Nutr 84(6):1489–1497

Zampelas A, Panagiotakos DB, Pitsavos C, Das UN, Chrysohoou C, Skoumas Y, Stefanadis C (2005) Fish consumption among healthy adults is associated with decreased levels of inflammatory markers related to cardiovascular disease: the ATTICA study. J Am Coll Cardiol 46(1):120–124. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2005.03.048

Yang M, Chung SJ, Floegel A, Song WO, Koo SI, Chun OK (2013) Dietary antioxidant capacity is associated with improved serum antioxidant status and decreased serum C-reactive protein and plasma homocysteine concentrations. Eur J Nutr. doi:10.1007/s00394-012-0491-5

Chun OK, Chung SJ, Claycombe KJ, Song WO (2008) Serum C-reactive protein concentrations are inversely associated with dietary flavonoid intake in U.S. adults. J Nutr 138(4):753–760

Yang M, Chung SJ, Floegel A, Song WO, Koo SI, Chun OK (2013) Dietary antioxidant capacity is associated with improved serum antioxidant status and decreased serum C-reactive protein and plasma homocysteine concentrations. Eur J Nutr 52(8):1901–1911. doi:10.1007/s00394-012-0491-5

Humfrey CD (1998) Phytoestrogens and human health effects: weighing up the current evidence. Nat Toxins 6(2):51–59. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1522-7189(199804)6:2<51:AID-NT11>3.0.CO;2-9

Patisaul HB, Jefferson W (2010) The pros and cons of phytoestrogens. Front Neuroendocrinol 31(4):400–419. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2010.03.003

Branca F, Lorenzetti S (2005) Health effects of phytoestrogens. Forum Nutr 57:100–111

Hallund J, Tetens I, Bugel S, Tholstrup T, Bruun JM (2008) The effect of a lignan complex isolated from flaxseed on inflammation markers in healthy postmenopausal women. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 18(7):497–502. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2007.05.007

Dodin S, Cunnane SC, Masse B, Lemay A, Jacques H, Asselin G, Tremblay-Mercier J, Marc I, Lamarche B, Legare F, Forest JC (2008) Flaxseed on cardiovascular disease markers in healthy menopausal women: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Nutrition 24(1):23–30. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2007.09.003

Pan A, Demark-Wahnefried W, Ye X, Yu Z, Li H, Qi Q, Sun J, Chen Y, Chen X, Liu Y, Lin X (2009) Effects of a flaxseed-derived lignan supplement on C-reactive protein, IL-6 and retinol-binding protein 4 in type 2 diabetic patients. Br J Nutr 101(8):1145–1149. doi:10.1017/S0007114508061527

Lampe JW, Atkinson C, Hullar MA (2006) Assessing exposure to lignans and their metabolites in humans. J AOAC Int 89(4):1174–1181

Nicastro HL, Mondul AM, Rohrmann S, Platz EA (2013) Associations between urinary soy isoflavonoids and two inflammatory markers in adults in the United States in 2005–2008. Cancer Causes Control 24(6):1185–1196. doi:10.1007/s10552-013-0198-9

Mondul AM, Selvin E, De Marzo AM, Freedland SJ, Platz EA (2010) Statin drugs, serum cholesterol, and prostate-specific antigen in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001–2004. Cancer Causes Control 21(5):671–678. doi:10.1007/s10552-009-9494-9

Johnson CL, Paulose-Ram R, Ogden C (2013) National health and nutrition examination survey: analytic guidelines, 1999-2010. Vital Health Stat 2(161):1–16

Penalvo JL, Lopez-Romero P (2012) Urinary enterolignan concentrations are positively associated with serum HDL cholesterol and negatively associated with serum triglycerides in U.S. adults. J Nutr 142(4):751–756. doi:10.3945/jn.111.150516

Barnes S, Coward L, Kirk M, Sfakianos J (1998) HPLC-mass spectrometry analysis of isoflavones. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 217(3):254–262

National Center for Health Statistics (2004) National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. 2001–2002 Data documentation, codebook, and frequencies

Valentin-Blasini L, Sadowski MA, Walden D, Caltabiano L, Needham LL, Barr DB (2005) Urinary phytoestrogen concentrations in the U.S. population (1999–2000). J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol 15(6):509–523. doi:10.1038/sj.jea.7500429

Rybak ME, Sternberg MR, Pfeiffer CM (2013) Sociodemographic and lifestyle variables are compound- and class-specific correlates of urine phytoestrogen concentrations in the U.S. population. J Nutr 143(6):986S–994S. doi:10.3945/jn.112.172981

Kelley-Hedgepeth A, Lloyd-Jones DM, Colvin A, Matthews KA, Johnston J, Sowers MR, Sternfeld B, Pasternak RC, Chae CU (2008) Ethnic differences in C-reactive protein concentrations. Clin Chem 54(6):1027–1037. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2007.098996

Timpson NJ, Nordestgaard BG, Harbord RM, Zacho J, Frayling TM, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Smith GD (2011) C-reactive protein levels and body mass index: elucidating direction of causation through reciprocal Mendelian randomization. Int J Obes (Lond) 35(2):300–308. doi:10.1038/ijo.2010.137

Kurzer MS (2003) Phytoestrogen supplement use by women. J Nutr 133(6):1983S–1986S

Davison S, Davis SR (2003) New markers for cardiovascular disease risk in women: impact of endogenous estrogen status and exogenous postmenopausal hormone therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88(6):2470–2478

Ridker PM, Hennekens CH, Rifai N, Buring JE, Manson JE (1999) Hormone replacement therapy and increased plasma concentration of C-reactive protein. Circulation 100(7):713–716

Frohlich M, Sund M, Lowel H, Imhof A, Hoffmeister A, Koenig W (2003) Independent association of various smoking characteristics with markers of systemic inflammation in men. Results from a representative sample of the general population (MONICA Augsburg Survey 1994/95). Eur Heart J 24(14):1365–1372

Alley DE, Seeman TE, Ki Kim J, Karlamangla A, Hu P, Crimmins EM (2006) Socioeconomic status and C-reactive protein levels in the US population: nHANES IV. Brain Behav Immun 20(5):498–504. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2005.10.003

Pradhan AD, Manson JE, Rifai N, Buring JE, Ridker PM (2001) C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA 286(3):327–334

Panichi V, Migliori M, De Pietro S, Taccola D, Bianchi AM, Norpoth M, Metelli MR, Giovannini L, Tetta C, Palla R (2001) C reactive protein in patients with chronic renal diseases. Ren Fail 23(3–4):551–562

Hage FG (2013) C-reactive protein and hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. doi:10.1038/jhh.2013.111

Adlercreutz H (2007) Lignans and human health. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 44(5–6):483–525. doi:10.1080/10408360701612942

Wang CS, Sun CF (2009) C-reactive protein and malignancy: clinico-pathological association and therapeutic implication. Chang Gung Med J 32(5):471–482

Valentin-Blasini L, Blount BC, Caudill SP, Needham LL (2003) Urinary and serum concentrations of seven phytoestrogens in a human reference population subset. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol 13(4):276–282. doi:10.1038/sj.jea.7500278

Adolphe JL, Whiting SJ, Juurlink BH, Thorpe LU, Alcorn J (2010) Health effects with consumption of the flax lignan secoisolariciresinol diglucoside. Br J Nutr 103(7):929–938. doi:10.1017/S0007114509992753

van der Schouw YT, Sampson L, Willett WC, Rimm EB (2005) The usual intake of lignans but not that of isoflavones may be related to cardiovascular risk factors in U.S. men. J Nutr 135(2):260–266

Gaskins AJ, Wilchesky M, Mumford SL, Whitcomb BW, Browne RW, Wactawski-Wende J, Perkins NJ, Schisterman EF (2012) Endogenous reproductive hormones and C-reactive protein across the menstrual cycle: the BioCycle Study. Am J Epidemiol 175(5):423–431. doi:10.1093/aje/kwr343

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Swiss Foundation for Nutrition Research (SFEFS; Zürich, Switzerland). We thank all individuals at the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention who were responsible for the planning and administering of NHANES.

Conflict of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Eichholzer, M., Richard, A., Nicastro, H.L. et al. Urinary lignans and inflammatory markers in the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2004 and 2005–2008. Cancer Causes Control 25, 395–403 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-014-0340-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-014-0340-3