Abstract

Purpose

Persistent smoking among cancer survivors may increase their risk of subsequent malignancies, including tobacco-related malignancies. Despite these risks, nearly 40 % of women diagnosed with cervical cancer continue to smoke after diagnosis. This study describes the relative risk of developing any subsequent and tobacco-related malignancy among cervical cancer survivors.

Methods

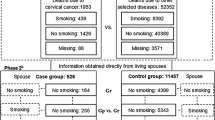

We examined data from the year 1992 to 2008 in 13 Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results registries. We calculated the standardized incidence ratio (SIR) and 95 % confidence limits (CLs) for all subsequent and tobacco-related malignancies among cervical cancer survivors. Tobacco-related malignancies were defined according to the 2004 Surgeon General’s Report on the Health Consequences of Smoking. For comparison with cervical cancer survivors, SIRs for subsequent malignancies were also calculated for female survivors of breast or colorectal cancers.

Results

The SIR of developing a subsequent tobacco-related malignancy was higher among cervical cancer survivors (SIR = 2.2, 95 % CL = 2.0–2.4). Female breast (SIR = 1.1, 95 % CL = 1.0–1.1) and colorectal cancer survivors (1.1, 1.1–1.2) also had an elevated risk. The increased risk of a subsequent tobacco-related malignancy among cervical cancer survivors was greatest in the first 5 years after the initial diagnosis and decreased as time since diagnosis elapsed.

Conclusion

Women with cervical cancer have a two-fold increased risk of subsequent tobacco-related malignancies, compared with breast and colorectal cancer survivors. In an effort to decrease their risk of subsequent tobacco-related malignancies, cancer survivors should be targeted for tobacco prevention and cessation services. Special attention should be given to cervical cancer survivors whose risk is almost twice that of breast or colorectal cancer survivors.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2011) Cancer survivors—United States, 2007. MMWR 60:269–272

Ries LAG, Melbert D, Krapcho M et al (2007) SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2004. National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD. Year. Available at URL: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2004/ based on November 2006 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER website, 2007. Published in 2007

Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Gilbert ES et al (2007) Second cancers among 104,760 survivors of cervical cancer: evaluation of long-term risk. J Natl Cancer Inst 99(21):1634–1643

Kleinerman RA, Kosary C, Hildesheim A (2006) New malignancies following cancer of the cervix uteri, vagina, and vulva. In: New malignancies among cancer survivors: SEER cancer registries, 1973–2000. NIH Publ. No. 05-5302. National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, pp 207–229

Balamurugan A, Ahmed F, Saraiya M et al (2008) Potential role of human papillomavirus in the development of subsequent primary in situ and invasive cancers among cervical cancer survivors. Cancer 113(10 Suppl):2919–2925

Tucker MA, Murray N, Shaw EG et al (1997) Second primary cancers related to smoking and treatment of small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer Working Cadre. J Natl Cancer Inst 89(23):1782–1788

Wynder EL, Mushinski MH, Spivak JC (1977) Tobacco and alcohol consumption in relation to the development of multiple primary cancers. Cancer 40(4 Suppl):1872–1878

Klosky JL, Tyc VL, Garces-Webb DM, Buscemi J, Klesges RC, Hudson MM (2007) Emerging issues in smoking among adolescent and adult cancer survivors: a comprehensive review. Cancer 110(11):2408–2419

Mayer DK, Carlson J (2011) Smoking patterns in cancer survivors. Nicotine Tob Res 13(1):34–40

Coups EJ, Ostroff JS (2005) A population-based estimate of the prevalence of behavioral risk factors among adult cancer survivors and noncancer controls. Prev Med 40(6):702–711

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Vital Signs. Smoking and Tobacco Use. Atlanta, GA. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/vital_signs/index.htm. Accessed August, 29 2011

The 2004 United States Surgeon General’s Report: The Health Consequences of Smoking (2004) N S W Public Health Bull 15(5–6):107

Botteri E, Iodice S, Bagnardi V, Raimondi S, Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P (2008) Smoking and colorectal cancer. J Am Med Assoc 300(23):2765

Johnson KC, Miller AB, Collishaw NE et al (2011) Active smoking and secondhand smoke increase breast cancer risk: the report of the canadian expert panel on tobacco smoke and breast cancer risk (2009). Tobacco Control 20(1):e2

Henley SJ, King JB, German RR, Richardson LC, Plescia M (2010) Surveillance of screening-detected cancers (colon and rectum, breast, and cervix)—United States, 2004–2006. MMWR Surveill Summ 59(9):1–25

Curtis RE, Freedman DM, Ron E, Ries LAG, Hacker DG, Edwards BK, Tucker MA, Fraumeni JF Jr (eds) (2006). New malignancies among cancer survivors: SEER cancer registries, 1973–2000. National Cancer Institute, NIH Publ. No. 05-5302, Bethesda, MD

Johnson CH (Ed) (2004) SPCaSM, revision 1. National Cancer Institute, NIH Publ. No. 04-5581, Bethesda, MD

Mould RF, Barrett A (1976) New primary cancers in patients originally presenting with carcinoma of the cervix. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 83(1):81–85

Saraiya M, Ahmed F, Krishnan S, Richards TB, Unger ER, Lawson HW (2007) Cervical cancer incidence in a prevaccine era in the United States, 1998–2002. Obstet Gynecol 109(2 Pt 1):360–370

Yabroff KR, Lawrence WF, King JC et al (2005) Geographic disparities in cervical cancer mortality: what are the roles of risk factor prevalence, screening, and use of recommended treatment? J Rural Health 21(2):149–157

Swan J, Breen N, Coates RJ, Rimer BK, Lee NC (2003) Progress in cancer screening practices in the United States: results from the 2000 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer 97(6):1528–1540

Seeff LC, McKenna MT (2003) Cervical cancer mortality among foreign-born women living in the United States, 1985 to 1996. Cancer Detect Prev 27(3):203–208

Munoz N, Bosch FX, de Sanjose S et al (2003) Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer. N Engl J Med 348(6):518–527

HPV Associated Cancers. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention A, GA. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/basic_info/

Castle PE (2008) How does tobacco smoke contribute to cervical carcinogenesis? J Virol 82(12):6084–6085; author reply 6085–6086

Hildesheim A, Schiffman MH, Gravitt PE et al (1994) Persistence of type-specific human papillomavirus infection among cytologically normal women. J Infect Dis 169(2):235

Giuliano AR, Sedjo RL, Roe DJ et al (2002) Clearance of oncogenic human papillomavirus (HPV) infection: effect of smoking (United States). Cancer Causes Control 13(9):839–846

Bellizzi KM, Rowland JH, Jeffery DD, McNeel T (2005) Health behaviors of cancer survivors: examining opportunities for cancer control intervention. J Clin Oncol 23(34):8884–8893

Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E (Eds) (2006) From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in transition. Committee on cancer survivorship: improving care and quality of life. National Academies Press, Washington, DC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2004) A national action plan for cancer survivorship: advancing public health strategies. US Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, GA

National Institutes of Health (NIH) (2011) NCI, surveillance epidemiology and end results (SEER). SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Cervix Uteri. Bethesda: NCI, 2011. Accessed http://www.seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/cervix.html. Accessed May 30 2011

Do KA, Johnson MM, Doherty DA et al (2003) Second primary tumors in patients with upper aerodigestive tract cancers: joint effects of smoking and alcohol (United States). Cancer Causes Control 14(2):131–138

Wingo PA, Jamison PM, Hiatt RA et al (2003) Building the infrastructure for nationwide cancer surveillance and control–a comparison between the National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR) and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program (United States). Cancer Causes Control 14(2):175–193

Boice J Jr, Land C, Preston D (1996) Ionizing radiation: cancer epidemiology and prevention. Oxford University Press, New York

Waggoner SE (2003) Cervical cancer. Lancet 361(9376):2217–2225

Swan J, Breen N, Coates RJ, Rimer BK, Lee NC (2003) Progress in cancer screening practices in the United States. Cancer 97(6):1528–1540

Boice J Jr, Day N, Andersen A et al (1985) Second cancers following radiation treatment for cervical cancer. An international collaboration among cancer registries. J Natl Cancer Inst 74(5):955

SEER Cancer Stat Fact Sheets. National Cancer Institute. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Underwood, J.M., Rim, S.H., Fairley, T.L. et al. Cervical cancer survivors at increased risk of subsequent tobacco-related malignancies, United States 1992–2008. Cancer Causes Control 23, 1009–1016 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-012-9957-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-012-9957-2