Abstract

Objective

To investigate the association between selenium and the risk of Barrett’s esophagus (BE), the precursor lesion of esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Methods

Data from the prospective Netherlands Cohort Study were used. This cohort study was initiated in 1986, when 120,852 subjects aged 55–69 years completed a questionnaire on dietary habits and lifestyle, and provided toenail clippings for the determination of baseline selenium status. After 16.3 years of follow-up, 253 BE cases (identified through linkage with the nationwide Dutch pathology registry) and 2,039 subcohort members were available for case–cohort analysis. Cox proportional hazards models were used to calculate incidence rate ratios (RR).

Results

The multivariable-adjusted RR for the highest versus the lowest quartile of toenail selenium was 1.06 (95% CI 0.71–1.57). No dose–response trend was seen (p trend = 0.99). No association was found in subgroups defined by sex, smoking status, body mass index (BMI), or intake of antioxidants. For BE cases that later progressed to high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma, the RR for a selenium level above the median vs. below the median was 0.64 (95% CI 0.24–1.76).

Conclusions

In this large prospective cohort study, we found no evidence of an association between selenium and risk of BE.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Barrett’s esophagus (BE) is a disease of the distal esophagus. Normally, the esophagus is lined with stratified squamous epithelium, which is replaced by a single layer of columnar epithelium (metaplasia) in BE patients. Diagnostic criteria for BE differ across the world. In the USA, the presence of goblet cells (indicating specialized intestinal metaplasia, SIM) is required for the diagnosis of BE [1], while in the United Kingdom, any type of metaplasia is sufficient for the diagnosis of BE [2]. In the Netherlands, both definitions have been used by different pathologists over time.

BE is most common in middle-aged Caucasian men [3] and in the Netherlands, the incidence is rising among men and women [4]. BE has primarily been of interest because patients are at increased risk to develop adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. The reported risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma in BE patients is highly variable between publications and was found in a recent meta-analysis to be between 4.1/1,000 and 6.1/1,000 person-years [5]. Patients in whom high-grade dysplasia is present in the BE tissue are at highest risk of developing esophageal adenocarcinoma [6].

Gastroesophageal reflux disease has been identified as a strong risk factor for BE, and possibly overweight or obesity are risk factors as well [7]. Lifestyle factors, including diet, may also play a role in BE etiology [7–9], but little information is available on this topic.

One dietary factor of interest is selenium, a trace element, which has been investigated for its possible role in cancer etiology. Selenium is involved in various anticarcinogenic processes and may act at a number of stages in cancer development [13]. Selenium is incorporated into some selenoproteins including glutathione peroxidases (GPx), which are antioxidant enzymes and protect against oxidative damage. Selenium is further involved in the alteration of DNA methylation, blockage of the cell cycle, induction of apoptosis, and inhibition of angiogenesis [13]. Selenium has been associated with several cancers: it may protect against prostate, lung, gastric, and colorectal cancer [10–12]. Moreover, we recently found evidence suggestive of an inverse association with esophageal adenocarcinoma. This association was found in women, never smokers, and persons with a low intake of antioxidants [14]. We identified only one study that looked into the association between selenium and BE. That study found a lower average serum selenium concentration among patients with BE than among controls, indicating a possible inverse association. Unfortunately, no measure of relative risk or multivariable-adjusted results were presented. Two cross-sectional studies among BE cases in the USA found indications for an inverse association between serum selenium and markers of progression of BE [15, 16]. Further, a recent study reported promotor hypermethylation of the gene coding for the selenoprotein GPx3 in Barrett’s esophagus tissue, thereby epigenetically inactivating this gene [17]. We hypothesize that selenium status is inversely associated with risk of BE, if selenium is involved early in the process of carcinogenesis.

The selenium content of our food may vary considerably between varieties of the same type of food, depending on the soil where the food was grown [18]. For that reason, selenium intake from diet cannot be estimated reliably using questionnaires. Selenium status is therefore often measured using biomarkers. In this study, we used toenails as a biomarker of selenium intake. Toenails are a suitable biomarker, because they reflect the intake of selenium for a period up to 1 year [19, 20].

Within the prospective Netherlands Cohort Study on diet and cancer, we investigated whether toenail selenium levels were inversely associated with the risk of BE.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

The prospective Netherlands Cohort Study on diet and cancer was started in September 1986, when 58,279 Dutch men and 62,573 women aged 55–69 were enrolled. The subjects were selected at random from 204 Dutch municipal registries. All cohort members completed a self-administered questionnaire and were requested to provide toenail clippings at baseline. The study was described in detail previously [21].

A case–cohort approach [22] was used for data processing and analysis for efficiency; case subjects were derived from the entire cohort, and the number of person-years at risk for the entire cohort was estimated from a subcohort of 3,500 subjects who were selected at random from the full cohort at baseline.

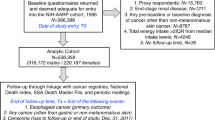

The subcohort was followed-up for vital status and after 16.3 years (September 1986 to December 2002), only one male subcohort member was lost to follow-up. We excluded subcohort members who reported having prevalent BE or cancer (other than skin cancer) at baseline (Fig. 1).

Flow diagram of subcohort members and Barrett’s esophagus cases on whom the analyses were based. a For reasons of efficiency, toenail material of Barrett’s esophagus cases were not sent to laboratory for instrumental neutron activation analysis for the determination of selenium levels, if they had incomplete or inconsistent questionnaire data. Therefore, this exclusion criterion did not anymore lead to exclusion of cases at this stage

The Medical Ethics Committee of Maastricht University, the Netherlands, has approved the study.

Follow-up for BE incidence

Incident BE cases in the total cohort were detected by computerized record linkage to the nationwide network and registry of histopathology and cytopathology in the Netherlands (PALGA) [23]. This network was founded in 1971, and an increasing number of laboratories joined PALGA such that it has a nationwide coverage since 1991. Due to this incomplete coverage, we may have missed BE cases diagnosed between baseline (1986) and 1991. We calculated how many cases we may have missed by multiplying the mean number of cases per year during the period a laboratory was connected by the number of years the laboratory was not connected to PALGA. This was done for each laboratory. This way we calculated that we may have missed approximately 3% of BE cases. At each of the 64 pathology laboratories in the Netherlands, excerpts of all pathology reports are generated automatically. Each excerpt contains a so-called PALGA diagnosis that describes topography, morphology, function, procedure, and disease. These excerpts are transferred to a central databank [23]. The linkage with PALGA was carried out for 16.3 years of follow-up [24]. All links were then manually checked for false-positives.

Thereafter, one pathologist (A.L.C.D.) and one pathologist in training (C.J.R.H.), who were blinded to the exposure status (i.e., the selenium status) of the cases, reviewed the excerpts of all pathology records to extract information on the initial date of diagnosis of BE, the type of metaplasia, and the degree of dysplasia. Excluded were BE cases with an uncertain diagnosis, or a diagnosis specifying the presence of only non-intestinal-type metaplasia. Also excluded were cases with a diagnosis of esophageal or gastric cancer before or less than a half year after the diagnosis of BE, and BE cases that were prevalent at baseline (Fig. 1).

Two definitions of BE were used: our primary case definition included only subjects with esophageal SIM. The secondary case definition included subjects (a) fulfilling the primary case definition or (b) with a pathology report stating ‘Barrett’s’, without a description of the type of metaplasia. Furthermore, BE cases may progress to high-grade dysplasia or esophageal adenocarcinoma. We followed the BE cases until December 31, 2002 and we identified the subgroup of BE cases who showed one of these complications. For analyses of BE cases who progressed to esophageal adenocarcinoma, we selected only BE cases in whom the adenocarcinoma was diagnosed more than a half year after the diagnosis of BE. This time lag was chosen to be more sure that this was a new diagnosis of cancer that followed the BE.

Exposure data

In our cohort, about 75% of the subjects provided toenail clippings. Toenail selenium determinations were carried out by the Reactor Institute Delft (Delft University of Technology, Delft, the Netherlands). The determination was based on instrumental neutron activation analysis of the 77mSe isotope (half-life 17.5 s). Each sample went through 6 cycles of 17-s irradiation at a thermal neutron flux of 3 × 1016 m−2s−1, 3-s decay, and 17-s counting at 1 cm from a 40% germanium detector. This method, its accuracy and precision, and the use in the Netherlands Cohort Study have been described in more detail previously [25–28].

In 1992, the toenail selenium determinations for the subcohort members were carried out (for the purpose of analysis of the association between selenium and risk of several cancers). In 2008, the toenail selenium determinations were carried out for the BE cases. In 1992, the ‘SBP’ facility was used for instrumental neutron activation analysis, and since 1996, the ‘CAFIA’ facility has been used. To assess the comparability of these two methods, the toenail selenium levels for 40 subcohort members were assessed in 1996 with the ‘CAFIA’ facility in addition to the original assessment with the ‘SBP’ facility [25]. The mean (SD) selenium level assessed by the ‘CAFIA’ facility [0.552 (0.05) μg/g] was comparable with mean selenium levels assessed by the ‘SBP’ facility [0.551 (0.04) μg/g] for these subjects. The Pearson correlation coefficient between toenail selenium levels assessed by the ‘CAFIA’ facility and that estimated by the ‘SBP’ facility was 0.95 (p < 0.01) [25]. It was concluded that both methods were comparable.

In 1992, all toenail clippings provided were sent to the Reactor Institute Delft for selenium determination. This determination, however, yields unreliable results if the nails weigh <10 mg and these measurements were thus excluded. In 2007, we discovered that toenail clippings can also be used as a source of DNA [29]. We therefore separated and saved 10–20 mg of toenail clippings from the BE cases. If afterward more than 10 mg of toenail clippings were left, we sent them to the Reactor Institute Delft for selenium determination. In case there were problems with the determination of toenail selenium, the subject was excluded (Fig. 1).

The self-administered questionnaire, which was filled out by all cohort members at baseline, consisted of a 150-item food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) and other questions, e.g., on smoking, education, height, weight, and use of medication. The FFQ asked about habitual consumption in the year before the start of the study. We calculated mean daily nutrient intakes using the Dutch food-composition table [30]. The questionnaire data were key entered and processed in a standardized manner, blinded with respect to cases/subcohort status to minimize observer bias in coding and interpretation of the data.

Statistical analysis

To evaluate the potential influence of prediagnostic BE at baseline on toenail selenium levels, cases were categorized according to the year of follow-up in which they were diagnosed. The mean toenail selenium levels of the cases according to the year of follow-up were compared, and differences were tested using a t-test. For the t-test, selenium levels were ln-transformed to normalize the distribution. For the case–cohort analysis, toenail selenium levels were categorized into quartiles according to the distribution in the subcohort. For continuous analysis, a 0.06 μg/g increment in toenail selenium was chosen. This is equal to the average size of the two central quartiles.

We excluded subjects who had inconsistent or incomplete dietary questionnaire data, because dietary data were needed as potential confounders and in subgroup analyses [31]. Subjects with missing data on the confounders were also excluded (Fig. 1).

The following variables were considered confounders and included in the multivariable regression model: age, sex, cigarette smoking (current yes/no, number of cigarettes/day, and number of smoking years), alcohol consumption (g/day), and body mass index (kg/m2). The following variables were considered potential confounders, but were not included in the models because they did not change the incidence rate ratio (RR) by >5%: highest level of education, family history of esophageal or gastric cancer, reported long-term (>0.5 years) use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or aspirin, or lower esophageal sphincter-relaxing medication [32], non-occupational physical activity, daily intakes of the antioxidants vitamin C, vitamin E, α-carotene, β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, lycopene, and lutein/zeaxanthin. Figure 1 shows that complete data were available for 2,039 subcohort members, 253 BE cases fulfilling the primary case definition, and 346 BE cases fulfilling the secondary case definition.

Multivariable-adjusted RR and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated using Cox proportional hazards models [33] in Stata 9.2 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA). Standard errors were estimated using the robust Huber–White sandwich estimator to account for additional variance introduced by sampling from the cohort. This method is equivalent to the variance–covariance estimator by Barlow [34]. We tested the proportional hazards assumption using the scaled Schoenfeld residuals [35]. Tests for dose–response trends were assessed by fitting ordinal exposure variables as continuous terms. Two-sided p values are reported throughout the article. The significance level α was set at 0.05.

We investigated possible interactions between toenail selenium status and sex, cigarette smoking status, BMI, and intakes of several antioxidants by estimating RR in strata of these exposures. The p value for interaction was assessed by including a cross-product term in the model. To evaluate potential differences in the association during early and late follow-up, we stratified our analysis by follow-up period. Finally, we analyzed the subgroup of BE cases that progressed to high-grade dysplasia and/or esophageal adenocarcinoma during follow-up until 2002, as this is the group most relevant with respect to disease burden. Because of the low number of cases in this subgroup (n = 21), we used two instead of four exposure categories: above and below the median selenium concentration.

Results

Descriptives

Table 1 shows the mean toenail selenium levels of BE cases, stratified by 2-year follow-up periods in which they were diagnosed. The toenail selenium levels in the first two follow-up years were lower than in later follow-up years, and this difference was borderline statistically significant (p = 0.07) for BE cases with SIM. As this difference may indicate an effect of prediagnostic disease on toenail selenium levels, we decided to exclude the first 2 years of follow-up from the analysis to prevent bias.

Characteristics of the subcohort and BE cases are described in Table 2. Subcohort members had a median toenail selenium level of 0.553 μg/g, with lower levels in men (median 0.539 μg/g) than in women (0.564 μg/g). The median toenail selenium levels in the two BE case groups were comparable (0.552 and 0.553 μg/g). With respect to other characteristics, there were more men and former smokers among the cases, when compared with the subcohort. Furthermore, cases had somewhat lower intakes of carotenoids and were more likely to be long-term users of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs/aspirin and lower esophageal sphincter-relaxing medication.

Main analysis

Table 3 presents multivariable-adjusted RR of BE according to toenail selenium levels. The RR of BE with SIM was 1.06 (95% CI: 0.71, 1.57) for the highest versus the lowest quartile of toenail selenium, and no dose–response trend was observed (p trend = 0.99). Multivariable analyses stratified by sex showed some differences in associations for men (RR quartile 4 vs. quartile 1 = 1.31, 95% CI: 0.78, 2.21) and women (RR quartile 4 vs. quartile 1 = 0.85, 95% CI: 0.46, 1.57), but the interaction between toenail selenium and sex was not statistically significant (p interaction = 0.18). The results were all comparable to the age- and sex-adjusted results (Table 3). When we used the less stringent secondary case definition of BE, the results were very similar to those based on the primary case definition (Table 3).

Interaction and subgroup analyses

When analyses were performed in strata of smoking status, body mass index, or daily intake of antioxidants, no statistically significant or important differences in associations were observed between strata, and the RR were all around unity. Again, results were similar for the two BE case groups (see Supplemental Table 1). Analyses stratified by follow-up period (early vs. late follow-up) showed no statistically significant associations or dose–response trends in either period (data not shown).

An inverse association was found between toenail selenium and risk of BE that progressed to high-grade dysplasia and/or adenocarcinoma (Table 4). The multivariable RR for a toenail selenium level above the median vs. below the median was 0.64, although the confidence interval was relatively wide (95% CI: 0.24, 1.76), due to the low case number in this analysis (n = 21).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the second investigation, and first cohort study, into the possible role of selenium in the etiology of BE, a precursor lesion of esophageal adenocarcinoma. The results from this prospective cohort study do not support our hypothesis that an inverse association might exist. Neither did we find evidence of an association in subgroups defined by sex, smoking status, BMI, intake of antioxidants or follow-up period.

The Dutch population that was used in this study has a low to moderate toenail selenium level (mean: 0.564 μg/g in the subcohort) when compared with mean levels found in other populations (general population or control subjects): China (Sichuan province) 0.211 μg/g [36], Finland 0.47 μg/g [37], USA 0.83–0.92 μg/g [38], Colombia 0.945 μg/g [39], and USA (South Dakota/Wyoming) 1.517 μg/g [19].

In the Netherlands, both the US and UK case definitions of BE may have been used. The use of these definitions may have changed over time, and different pathologists may have used different definitions.

The first strength of our study is its prospective character, which brings the advantage of measuring the selenium status before the diagnosis of BE. This method makes it unlikely that the exposure was changed due to the disease or knowledge of the diagnosis and therefore it lowers the chance of reversed causation. A second strength is the size of the study. This study had 80% power to detect an RR of 0.63 for all BE cases and an RR of 0.59 for BE cases with SIM [40]. Thirdly, we had the possibility to adjust for confounding by several lifestyle factors. A fourth strength is the use of toenail clippings for the measurement of selenium exposure, because selenium levels in clippings from all toes represent an exposure period of up to 1 year. Measuring long-term exposure is important as it more likely represents the exposure in the etiologically relevant time window compared with a measure of short-term exposure.

A limitation of our study is the lack of information about gastroesophageal reflux disease and medications related to this disease. In the baseline questionnaire, one question concerned the long-term use of medications and the disease for which these were prescribed. However, we believe that the reported use of reflux medication and antacids, and the presence of gastroesophageal reflux disease were substantially lower than the actual frequency. This prohibited us to use this information in the analysis. Consequently, we were not able to evaluate if gastroesophageal reflux disease is a confounder or intermediate factor in the relation between selenium and BE. We therefore suggest that this study is replicated in a population for which information on gastroesophageal reflux is available, to evaluate its possible role as confounder or intermediate factor. A second limitation is the single measurement of the exposure. Selenium exposure may have changed during follow-up due to changed selenium levels in foods or changed dietary habits. Third, we did not have the opportunity to verify the absence of BE in the subcohort members who were not diagnosed with BE. BE usually occurs in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease, but it has also been described in asymptomatic individuals, who are therefore not diagnosed with the disease. Three studies investigated the prevalence of BE among asymptomatic individuals in the USA and reported prevalences ranging from 1 to 25% [41–43]. However, in our cohort study, any undiagnosed BE cases would most likely not have influenced the RR. This is because the imperfect sensitivity (i.e., false-negatives) is combined with good specificity (i.e., few false-positives), and the chance of diagnosis is likely independent of selenium status. The misclassification of the disease status then is non-differential and will not influence the RR [44]. Still, a consequence of undiagnosed cases is a reduced power to detect an existing association. A fourth limitation, related to the third, is caused by the incomplete coverage of the Netherlands by PALGA before 1991. There may have been some BE cases that were diagnosed in laboratories when these had not yet joined PALGA. If these cases were not followed-up, we missed their diagnosis. If they were followed-up after the laboratory joined PALGA, the incidence date we registered is more recent than the true incidence date. We assessed that we may have missed 3% of the BE cases in our cohort at most.

If in line with our null findings, there is truly no association between toenail selenium and the risk of BE, this does not preclude a possible association between selenium and progression of BE to high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma. We observed an RR well below unity for subjects with a toenail selenium level above the median in those BE cases who progressed to high-grade dysplasia and/or esophageal adenocarcinoma. This RR, however, was based on few cases and was not statistically significant. In a previous analysis, we found indications for an inverse association between selenium and risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma in some subgroups: women, never smokers, and low antioxidant consumers [14]. These above-mentioned observations are in agreement with observations by two other studies that found indications for a role of selenium in later stages of the carcinogenesis of esophageal adenocarcinoma [15, 16]. Selenium might be an interesting preventive agent for progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma in patients with BE, but this requires a larger body of evidence.

In conclusion, no evidence of an inverse association between toenail selenium and risk of BE was found in this study. An inverse association might exist for BE cases that progress to high-grade dysplasia and/or esophageal adenocarcinoma, but results from other studies are needed before any firm conclusions can be drawn. Preferably, future studies should have a prospective character and should have the possibility to investigate the role of gastroesophageal reflux in this association. Also, it would be informative to study the relation between selenium and risk of BE in a population with selenium levels that are lower or higher compared with our study population.

References

Wang KK, Sampliner RE (2008) Updated guidelines 2008 for the diagnosis, surveillance and therapy of Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol 103:788–797

Playford RJ (2006) New British society of gastroenterology (Bsg) guidelines for the diagnosis and management of Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut 55:442–443

Falk GW (2002) Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology 122:1569–1591

Post PN, Siersema PD, van Dekken H (2007) Rising incidence of clinically evident Barrett’s oesophagus in the Netherlands: a nation-wide registry of pathology reports. Scand J Gastroenterol 42:17–22

Yousef F, Cardwell C, Cantwell MM, Galway K, Johnston BT, Murray L (2008) The incidence of esophageal cancer and high-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol 168:237–249

Rastogi A, Puli S, El-Serag HB, Bansal A, Wani S, Sharma P (2008) Incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma in patients with Barrett’s esophagus and high-grade dysplasia: a meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc 67:394–398

Wild CP, Hardie LJ (2003) Reflux, Barrett’s oesophagus and adenocarcinoma: burning questions. Nat Rev Cancer 3:676–684

Anderson LA, Watson RG, Murphy SJ et al (2007) Risk factors for Barrett’s oesophagus and oesophageal adenocarcinoma: results from the FINBAR study. World J Gastroenterol 13:1585–1594

Kubo A, Levin TR, Block G et al (2008) Dietary patterns and the risk of Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Epidemiol 167:839–846

Navarro Silvera SA, Rohan TE (2007) Trace elements and cancer risk: a review of the epidemiologic evidence. Cancer Causes Control 18:7–27

World Cancer Research Fund, American Institute for Cancer Research (2007) Food, nutrition, physical activity and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective. AICR, Washington, DC

Clark LC, Combs GF Jr, Turnbull BW et al (1996) Effects of selenium supplementation for cancer prevention in patients with carcinoma of the skin. A randomized controlled trial. Nutritional prevention of cancer study group. JAMA 276:1957–1963

Rayman MP (2005) Selenium in cancer prevention: a review of the evidence and mechanism of action. Proc Nutr Soc 64:527–542

Steevens J, van den Brandt PA, Goldbohm RA, Schouten LJ (2010) Selenium status and the risk of esophageal and gastric cancer subtypes: the Netherlands cohort study. Gastroenterology 138:1704–1713

Rudolph RE, Vaughan TL, Kristal AR et al (2003) Serum selenium levels in relation to markers of neoplastic progression among persons with Barrett’s esophagus. J Natl Cancer Inst 95:750–757

Moe GL, Kristal AR, Levine DS, Vaughan TL, Reid BJ (2000) Waist-to-hip ratio, weight gain, and dietary and serum selenium are associated with DNA content flow cytometry in Barrett’s esophagus. Nutr Cancer 36:7–13

Peng DF, Razvi M, Chen H et al (2009) DNA hypermethylation regulates the expression of members of the Mu-class glutathione S-transferases and glutathione peroxidases in Barrett’s adenocarcinoma. Gut 58:5–15

Willett WC, Buzzard IM (1998) Foods and nutrients. In: Willett WC (ed) Monographs in epidemiology and biostatistics volume 30 nutritional epidemiology. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 18–32

Longnecker MP, Stram DO, Taylor PR et al (1996) Use of selenium concentration in whole blood, serum, toenails, or urine as a surrogate measure of selenium intake. Epidemiology 7:384–390

Hunter DJ, Morris JS, Chute CG et al (1990) Predictors of selenium concentration in human toenails. Am J Epidemiol 132:114–122

van den Brandt PA, Goldbohm RA, van ‘t Veer P, Volovics A, Hermus RJ, Sturmans F (1990) A large-scale prospective cohort study on diet and cancer in the Netherlands. J Clin Epidemiol 43:285–295

Barlow WE, Ichikawa L, Rosner D, Izumi S (1999) Analysis of case-cohort designs. J Clin Epidemiol 52:1165–1172

Casparie M, Tiebosch AT, Burger G et al (2007) Pathology data banking and bio banking in the Netherlands, a central role for plage, the nationwide histopathology and cytopathology data network and archive. Cell Oncol 29:19–24

van den Brandt PA, Schouten LJ, Goldbohm RA, Dorant E, Hunen PM (1990) Development of a record linkage protocol for use in the Dutch cancer registry for epidemiological research. Int J Epidemiol 19:553–558

Zeegers MP, Goldbohm RA, Bode P, van den Brandt PA (2002) Prediagnostic toenail selenium and risk of bladder cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 11:1292–1297

Bode P (2000) Automation and quality assurance in the neutron activation facilities in delft. J Radioanal Nucl Chem 245:127–132

van den Brandt PA, Goldbohm RA, van’t Veer P, Bode P, Hermus RJ, Sturmans F (1993) Predictors of toenail selenium levels in men and women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2:107–112

van den Brandt PA, Goldbohm RA, van ‘t Veer P et al (1993) A prospective cohort study on toenail selenium levels and risk of gastrointestinal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 85:224–229

van Breda SG, Hogervorst JG, Schouten LJ et al (2007) Toenails: an easily accessible and long-term stable source of DNA for genetic analyses in large-scale epidemiological studies. Clin Chem 53:1168–1170

Anonymous (1986) Nevo table: Dutch food composition table, 1986–1987. (Dutch). The Hague, Netherlands: Voorlichtingbureau Voor de Voeding

Goldbohm RA, van den Brandt PA, Brants HA et al (1994) Validation of a dietary questionnaire used in a large-scale prospective cohort study on diet and cancer. Eur J Clin Nutr 48:253–265

Lagergren J, Bergstrom R, Adami HO, Nyren O (2000) Association between medications that relax the lower esophageal sphincter and risk for esophageal adenocarcinoma. Ann Intern Med 133:165–175

Cox DR (1972) Regression models and life-tables. J Roy Statistical Society 34:187–220

Barlow WE (1994) Robust variance estimation for the case-cohort design. Biometrics 50:1064–1072

Schoenfeld D (1982) Partial residuals for the proportional hazards regression model. Biometrika 69:239–241

Gao S, Jin Y, Hall KS et al (2007) Selenium level and cognitive function in rural elderly Chinese. Am J Epidemiol 165:955–965

Ovaskainen ML, Virtamo J, Alfthan G et al (1993) Toenail selenium as an indicator of selenium intake among middle-aged men in an area with low soil selenium. Am J Clin Nutr 57:662–665

Garland M, Morris JS, Rosner BA et al (1993) Toenail trace element levels as biomarkers: reproducibility over a 6 year period. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2:493–497

Koriyama C, Campos FI, Yamamoto M et al (2008) Toenail selenium levels and gastric cancer risk in Cali, Colombia. J Toxicol Sci 33:227–235

Cai J, Zeng D (2004) Sample size/power calculation for case-cohort studies. Biometrics 60:1015–1024

Fan X, Snyder N (2009) Prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus in patients with or without gerd symptoms: role of race, age, and gender. Dig Dis Sci 54:572–577

Gerson LB, Shetler K, Triadafilopoulos G (2002) Prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus in asymptomatic individuals. Gastroenterology 123:461–467

Ward EM, Wolfsen HC, Achem SR et al (2006) Barrett’s esophagus is common in older men and women undergoing screening colonoscopy regardless of reflux symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol 101:12–17

Rothman KJ, Greenland S (1998) Precision and validity in epidemiologic studies. In: Rothman KJ, Greenland S (eds) Modern epidemiology, 2nd edn. Lippincott, Philadelphia, pp 115–134

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants of this study, the nationwide network and registry of histopathology and cytopathology in the Netherlands (PALGA), the laboratory for instrumental neutron activation analysis (INAA) of the Delft University of Technology, Dr. A. Kester for statistical advice, S. van de Crommert, H. Brants, J. Nelissen, C. de Zwart, and L. Oheimer for assistance, and H. van Montfort and J. Berben for programming assistance. This work was supported by the Dutch Cancer Society (grant number 2006–3562). The Dutch Cancer Society had no involvement in study design, in collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the report for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Steevens, J., Schouten, L.J., Driessen, A.L.C. et al. Toenail selenium status and the risk of Barrett’s esophagus: the Netherlands Cohort Study. Cancer Causes Control 21, 2259–2268 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-010-9651-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-010-9651-1