Abstract

This article explores managers’ views on various ways in which business schools can contribute to providing solid ethics education to their students, who will ultimately become the next generation of business leaders. One thousand top level managers of Icelandic firms were approached and asked a number of questions aimed at establishing their view on the relationship between ethics education and the role of business schools in forming and developing business ethics education. Icelandic businesses were badly hurt by the 2008 crisis, and therefore Iceland provides an interesting foundation for an empirical study of this sort as the aftermath of the crisis has encouraged managers to consciously reflect on the way their business was and should be conducted. Based on the results of the survey, a few main themes have developed. First, it appears that according to practicing managers, business schools should not be held responsible for employees’ unethical behavior. Nevertheless, managers believe that business schools should assist future employees in understanding ethics by including business ethics in teaching curricula. Second, managers believe that the workplace is not where ethics are learned, while also insisting that former students should already have strong ethical standards when entering the workplace. Third, managers call for business schools not only to contribute more to influencing students’ ethical standards, but also to reshape the knowledge and capabilities of practicing managers through re-training and continuous education. Based on the results of the study, the article also offers some recommendations on how to begin reformulating the approach to business ethics education in Iceland, and perhaps elsewhere.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bartlett, B. (2003). Management and business ethics: A critique and integration of ethical decision-making models. British Journal of Management, 14(3), 223–235.

Bitros, G. C., & Karayiannis, A. D. (2010). Entrepreneurial morality: Some indications from Greece. European Journal of International Management, 4(4), 333–361.

Bowie, N. E. (1991). Business ethics as a discipline: The search for legitimacy. In R. E. Freeman (Ed.), Business ethics: The state of the art (pp. 17–41). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bowie, N. E. (2000). Business ethics, philosophy, and the next 25 years. Business Ethics Quarterly, 10(1), 7–20.

Brinkmann, J., Sims, R. R., & Nelson, L. J. (2011). Business ethics across the curriculum? Journal of Business Ethics Education, 8, 83–104.

Cullen, J. B., Parboteeah, K. P., & Hoegl, M. (2004). Cross-national differences in managers’ willingness to justify ethically suspect behaviors: a test of institutional anomie theory. Academy of Management Journal, 47(3), 411–421.

Dyck, B., Walker, K., Starke, F. A., & Uggerslev, K. (2011). Addressing concerns raised by critics of business schools by teaching multiple approaches to management. Business and Society Review, 116(1), 1–27.

Evans, J. M., Trevino, L. K., & Weaver, G. R. (2006). Who’s in the ethics driver’s seat? Factors influencing ethics in the MBA curriculum. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 5(3), 278–293.

Eyjolfsdottir, H. M., & Smith, P. B. (1996). Icelandic business and management culture. International Studies of Management & Organization, 26(3), 61–72.

Ferrell, O. C., Fraedrich, J., & Ferrell, L. (2006). Business ethics: Ethical decision making and cases. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Giacalone, R. A., & Thompson, K. R. (2006). Business ethics and social responsibility education: Shifting the worldview. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 5(3), 266–277.

Heller, N. A., & Heller, V. L. (2011). Business ethics education: Are business schools teaching to the AACSB ethics education task force recommendations? International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2(20), 30–38.

Messner, S., & Rosenfeld, R. (1997). Political restraint of the market and levels of criminal homicide: A cross-national application of institutional-anomie theory. Social Forces, 75(4), 1393–1416.

Sigurjonsson, T. O. (2010). The Icelandic bank collapse: Challenges to governance and risk management. Corporate Governance, 10(1), 33–45.

Sigurjonsson, T. O. (2011). Privatization and deregulation: A chronology of events. In R. Z. Aliber & G. Zoega (Eds.), Preludes to the Icelandic financial crisis (pp. 26–40). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Sigurjonsson, T. O., & Mixa, M. W. (2011). Learning from the “Worst Behaved”: Iceland’s financial crisis and the Nordic comparison. Thunderbird International Business Review, 53(2), 209–224.

Special Investigation Commission (2010). Report of the special investigation commission. http://sic.althingi.is/.

Swanson, D. L., & Fisher, D. G. (2008). If we don’t know where we’re going, any road will take us there. In D. L. Swanson & D. G. Fisher (Eds.), Advancing business ethics education (pp. 1–23). Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Swanson, D. L., & Fisher, D. G. (2011). Toward assessing business ethics education. New York: Information Age Publishing.

Trevino, L. K. (1986). Ethical decision-making in organisations: A person-situation interactionist model. Academy of Management Review, 11(3), 601–617.

Trevino, L. K. (1992). Moral reasoning and business ethics: Implications for research, education and management. Journal of Business Ethics, 11(5,6), 445–459.

Vaiman, V., Davidsson, P. A., & Sigurjonsson, T. O. (2009). Revising a concept of corruption as a result of the global economic crisis—The case of Iceland. In A. Stachowicz-Stanusch (Ed.), Organizational immunity to corruption—Building theoretical and research foundations (pp. 363–372). Katowice: The Katowice Branch of the Polish Academy of Sciences.

Vaiman, V., Sigurjonsson, T. O., & Davidsson, P. A. (2011). Weak business culture as antecedents of economic crisis: The case of Iceland. Journal of Business Ethics, 98(2), 67–83.

Wade, R. (2009a). Robert Wade’s speech in Reykjavik. Retrieved from http://economicdisaster.wordpress.com/2009/01/13/robert-wades-speech-in-reykjavik/.

Wade, R. (2009b). Iceland as Icarus. Challenge, 52(3), 5–33.

Warren, R., & Tweedale, G. (2002). Business ethics and business history: Neglected dimensions in management education. British Journal of Management, 13(3), 209–219.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Questionnaire

Appendix: Questionnaire

-

1.

General questions

-

Any business is inherently unethical because of its emphasis upon profit-making.

-

Business ethics in Iceland is good compared to neighboring countries.

-

Business ethics during the economic downturn is weaker than in boom times.

-

Business ethics in Iceland has improved during 2009–2010.

-

In Iceland now ethics in business is better than ethics in politics.

-

Business ethics in Iceland is better in the public sector than in the private sector.

-

Business ethics is better in women than men.

-

Business ethics is better in older people than younger.

-

Favoritism (nepotism) is common in Icelandic business life.

-

Icelandic firms emphasize business ethics in their strategy.

-

Icelandic firms practice good business ethics.

-

-

2.

Please rank these industries according as how you view their business ethics, from best (1) to worst (6)

-

Financial/banking.

-

Auditing.

-

Professional services.

-

Retail.

-

Manufacturing/fishing.

-

IT.

-

-

3.

Questions on specific organizations

-

Our organization promotes stakeholder-centered worldview (i.e., aimed at benefitting employees, customers, investors, government, etc.), as opposed to a shareholder-centered one (i.e., aimed at benefitting shareholders only).

-

Thinking of good business ethics is high on our managers’ agenda.

-

In general, more educated people in our organization are more ethical in their decision making than less educated employees are.

-

In our organization we have formal guidelines regarding business ethics and ethical behavior.

-

Managers are made responsible if codes of ethics are broken.

-

Employees take the organization’s ethical stand seriously.

-

There are consequences if poor ethics is practiced in our organization.

-

Employees in our organization have a clear path to follow if they notice unethical behavior.

-

-

4.

During the past 2 years I have witnessed unethical business practices in our organization

-

Never.

-

1–2 times.

-

3–5 times.

-

More than 5 times.

-

-

5.

If your answer to last question was positive, please mention the type of unethical business practices you have experienced in the past 2 years.

-

6.

Please indicate in which way ethics might be lacking in Icelandic businesses.

-

7.

Questions on business students.

-

Business schools are responsible for the unethical business behavior displayed by their graduates.

-

It is a responsibility of business schools to help their students become more socially responsible and ethically sensitive.

-

Business students should have strong ethical standards before entering the workforce.

-

Business ethics is mostly learned at a workplace.

-

Business graduates are more ethical now than before 2008.

-

It should be mandatory for business students to learn about ethics at university.

-

-

8.

Business ethics was part of my curriculum at the university as

-

A stand-alone course.

-

An integral part of most subjects in the program.

-

Both.

-

Neither.

-

-

9.

The following should help students learn ethics in a more effective way.

-

A stand-alone ethics course.

-

Ethics as an integral part of every subject in the program.

-

Both.

-

-

10.

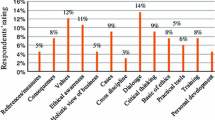

What is lacking in current business graduates in terms of their ethical standards?

-

11.

What is lacking in attempts of business schools to strengthen good ethics in business graduates?

-

12.

How should business ethics be taught at business schools? Please rank the following methods

-

Study fundamentals of business ethics.

-

Cases describing ethical dilemmas (training in problem solving).

-

Guest lecturers (managers) that dealt with ethical dilemmas.

-

Training aimed at teaching students to openly share their views (training for whistle blowing).

-

Providing practical “tools” on how to analyze and solve ethical dilemmas.

-

Other methods—answer in text box below

-

-

13.

Other methods

-

Background questions

-

-

14.

What is your graduation year?

-

Before 2003 · 2003–2008 · After 2008.

-

-

15.

What is your occupation?

-

Top level manager · Mid-level manager · Specialist · Faculty member at a university · Other.

-

-

16.

In what industry is your employer?

-

Financial/Banking · Auditing · Professional services · Retail · Manufacturing/Fishing · IT · Other.

-

-

17.

What is your gender?

-

Male · Female.

-

-

18.

What is your age?

-

Under 35 · 35–45 · 46–55 · 56 and older.

-

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sigurjonsson, T.O., Vaiman, V. & Arnardottir, A.A. The Role of Business Schools in Ethics Education in Iceland: The Managers’ Perspective. J Bus Ethics 122, 25–38 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1755-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1755-6