Abstract

Purpose

A prolonged time from first presentation to cancer diagnosis has been associated with worse disease-related outcomes. This study evaluated potential determinants of a long diagnostic interval among symptomatic breast cancer patients.

Methods

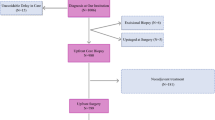

This was a population-based, cross-sectional study of symptomatic breast cancer patients diagnosed in Ontario, Canada from 2007 to 2015 using administrative health data. The diagnostic interval was defined as the time from the earliest breast cancer-related healthcare encounter before diagnosis to the diagnosis date. Potential determinants of the diagnostic interval included patient, disease and usual healthcare utilization characteristics. We used multivariable quantile regression to evaluate their relationship with the diagnostic interval. We also examined differences in diagnostic interval by the frequency of encounters within the interval.

Results

Among 45,967 symptomatic breast cancer patients, the median diagnostic interval was 41 days (interquartile range 20–92). Longer diagnostic intervals were observed in younger patients, patients with higher burden of comorbid disease, recent immigrants to Canada, and patients with higher healthcare utilization prior to their diagnostic interval. Shorter intervals were observed in patients residing in long-term care facilities, patients with late stage disease, and patients who initially presented in an emergency department. Longer diagnostic intervals were characterized by an increased number of physician visits and breast procedures.

Conclusions

The identification of groups at risk of longer diagnostic intervals provides direction for future research aimed at better understanding and improving breast cancer diagnostic pathways. Ensuring that all women receive a timely breast cancer diagnosis could improve breast cancer outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The dataset from this study is held securely in coded form at ICES. While data sharing agreements prohibit ICES from making the dataset publicly available, access may be granted to those who meet pre-specified criteria for confidential access, available at www.ices.on.ca/DAS. The full dataset creation plan and underlying analytic code are available from the authors upon request, understanding that the computer programs may rely upon coding templates or macros that are unique to ICES and are therefore either inaccessible or may require modification.

References

Richards MA (2009) The size of the prize for earlier diagnosis of cancer in England. Br J Cancer 101(S2):S125–S129. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6605402

Richards M, Westcombe A, Love S, Littlejohns P, Ramirez A (1999) Influence of delay on survival in patients with breast cancer: a systematic review. Lancet 353(9159):1119–1126. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02143-1

Neal RD (2009) Do diagnostic delays in cancer matter? Br J Cancer 101(S2):S9–S12. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6605384

Neal RD, Tharmanathan P, France B et al (2015) Is increased time to diagnosis and treatment in symptomatic cancer associated with poorer outcomes? Systematic review. Br J Cancer 112(S1):S92–S107. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2015.48

Butler J, Foot C, Bomb M et al (2013) The International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership: an international collaboration to inform cancer policy in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Health Policy 112(1–2):148–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.03.021

Weller D, Vedsted P, Anandan C et al (2016) An investigation of routes to cancer diagnosis in 10 international jurisdictions, as part of the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership: survey development and implementation. BMJ Open 6(7):e009641. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009641

Rose PW, Rubin G, Perera-Salazar R et al (2015) Explaining variation in cancer survival between 11 jurisdictions in the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership: a primary care vignette survey. BMJ Open 5(5):e007212–e007212. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007212

Weller D, Vedsted P, Rubin G et al (2012) The Aarhus statement: improving design and reporting of studies on early cancer diagnosis. Br J Cancer 106(7):1262–1267. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2012.68

Montgomery M, McCrone SH (2010) Psychological distress associated with the diagnostic phase for suspected breast cancer: systematic review: psychological distress associated with the diagnostic phase. J Adv Nurs 66(11):2372–2390. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05439.x

Brocken P, Prins JB, Dekhuijzen PNR, van der Heijden HFM (2012) The faster the better?-A systematic review on distress in the diagnostic phase of suspected cancer, and the influence of rapid diagnostic pathways. Psychooncology 21(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1929

Liao M-N, Chen M-F, Chen S-C, Chen P-L (2008) Uncertainty and anxiety during the diagnostic period for women with suspected breast cancer. Cancer Nurs 31(4):274–283. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NCC.0000305744.64452.fe

Tørring ML, Frydenberg M, Hansen RP, Olesen F, Vedsted P (2013) Evidence of increasing mortality with longer diagnostic intervals for five common cancers: a cohort study in primary care. Eur J Cancer 49(9):2187–2198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2013.01.025

Tørring ML, Frydenberg M, Hamilton W, Hansen RP, Lautrup MD, Vedsted P (2012) Diagnostic interval and mortality in colorectal cancer: U-shaped association demonstrated for three different datasets. J Clin Epidemiol 65(6):669–678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.12.006

Schutte HW, Heutink F, Wellenstein DJ et al (2020) Impact of time to diagnosis and treatment in head and neck cancer: a systematic review. Otolaryngol Neck Surg 162(4):446–457. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599820906387

Neal RD, Din NU, Hamilton W et al (2014) Comparison of cancer diagnostic intervals before and after implementation of NICE guidelines: analysis of data from the UK General Practice Research Database. Br J Cancer 110(3):584–592. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.791

Jiang L, Gilbert J, Langley H, Moineddin R, Groome PA (2018) Breast cancer detection method, diagnostic interval and use of specialized diagnostic assessment units across Ontario, Canada. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can 38(10):358–367. https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.38.10.02

Webber C, Jiang L, Grunfeld E, Groome PA (2017) Identifying predictors of delayed diagnoses in symptomatic breast cancer: a scoping review. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 26(2):e12483. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12483

Zapka J (2008) Innovative provider- and health system-directed approaches to improving colorectal cancer screening delivery. Med Care 46(Supplement 1):S62–S67. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817fdf57

Groome PA, Webber C, Whitehead M et al (2019) Determining the cancer diagnostic interval using administrative health care data in a breast cancer cohort. JCO Clin Cancer Inform 3:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1200/CCI.18.00131

Statistics Canada. Dictionary, Census of Population, 2016. Published November 15, 2017. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/ref/dict/az1-eng.cfm#R. Accessed 7 Mar 2019

Johns Hopkins University School of Public Heatlh. The Johns Hopkins ACG System. Version 10.0 Ed.; 2011

Sobin L, Gospodarowicz M, Wittekind C (eds) (2009) TNM classification of malignant tumours, 7th edn. Wiley-Blackwell, Hoboken

Frohlich N, Katz A, De Coster C, et al (2006) Profiling primary care physician practice in Manitoba. Published online

Hao L, Naiman D (2007) Quantile regression. Sage, London

Hamilton L (2015) The diagnostic interval of colorectal cancer patients in Ontario by degree of rurality. Published online

Webber C, Flemming J, Birtwhistle R, Rosenberg M, Groome P (2017) Wait times and patterns of care in the colorectal cancer diagnostic interval. Int J Popul Data Sci 1(1):191

Mounce LTA, Price S, Valderas JM, Hamilton W (2017) Comorbid conditions delay diagnosis of colorectal cancer: a cohort study using electronic primary care records. Br J Cancer 116(12):1536–1543. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2017.127

Brandenbarg D, Groenhof F, Siewers IM, van der Voort A, Walter FM, Berendsen AJ (2018) Possible missed opportunities for diagnosing colorectal cancer in Dutch primary care: a multimethods approach. Br J Gen Pract 68(666):e54–e62. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp17X693905

Walter FM, Emery JD, Mendonca S et al (2016) Symptoms and patient factors associated with longer time to diagnosis for colorectal cancer: results from a prospective cohort study. Br J Cancer 115(5):533–541. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2016.221

Bjerager M, Palshof T, Dahl R, Vedsted P, Olesen F (2006) Delay in diagnosis of lung cancer in general practice. Br J Gen Pract 56(532):863–868

Friese CR, Abel GA, Magazu LS, Neville BA, Richardson LC, Earle CC (2009) Diagnostic delay and complications for older adults with multiple myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma 50(3):392–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/10428190902741471

Teppo H, Alho O-P (2009) Comorbidity and diagnostic delay in cancer of the larynx, tongue and pharynx. Oral Oncol 45(8):692–695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.10.012

Renzi C, Kaushal A, Emery J et al (2019) Comorbid chronic diseases and cancer diagnosis: disease-specific effects and underlying mechanisms. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 16(12):746–761. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-019-0249-6

Lyratzopoulos G, Vedsted P, Singh H (2015) Understanding missed opportunities for more timely diagnosis of cancer in symptomatic patients after presentation. Br J Cancer 112(S1):S84–S91. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2015.47

Adam R, Garau R, Raja EA, Jones B, Johnston M, Murchie P (2017) Do patients’ faces influence General Practitioners’ cancer suspicions? A test of automatic processing of sociodemographic information. PLoS One 12(11):e0188222. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0188222

Jensen H, Tørring ML, Olesen F, Overgaard J, Vedsted P (2014) Cancer suspicion in general practice, urgent referral and time to diagnosis: a population-based GP survey and registry study. BMC Cancer 14(1):636. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-14-636

Foxcroft LM, Evans EB, Porter AJ (2004) The diagnosis of breast cancer in women younger than 40. Breast 13(4):297–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2004.02.012

Talbot Y, Fuller-Thomson E, Tudiver F, Habib Y, McIsaac WJ (2001) Canadians without regular medical doctors. Who are they? Can Fam Physician 47:58–64

Glazier R, Hutchison B, Kopp A (2015) Comparison of family health teams to other Ontario primary care models, 2004/05 to 2011/12. ICES

Crawford J, Ahmad F, Beaton D, Bierman AS (2016) Cancer screening behaviours among South Asian immigrants in the UK, US and Canada: a scoping study. Health Soc Care Community 24(2):123–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12208

Kalich A, Heinemann L, Ghahari S (2016) A scoping review of immigrant experience of health care access barriers in Canada. J Immigr Minor Health 18(3):697–709. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-015-0237-6

Ahmed S, Lee S, Shommu N, Rumana N, Turin T (2017) Experiences of communication barriers between physicians and immigrant patients: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. Patient Exp J 4(1):122–140. https://doi.org/10.35680/2372-0247.1181

Murchie P, Raja EA, Brewster DH et al (2014) Time from first presentation in primary care to treatment of symptomatic colorectal cancer: effect on disease stage and survival. Br J Cancer 111(3):461–469. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2014.352

Crawford SC (2002) The waiting time paradox: population based retrospective study of treatment delay and survival of women with endometrial cancer in Scotland. BMJ 325(7357):196–196. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.325.7357.196

Suhail A, Crocker CE, Das B, Payne JI, Manos D (2019) Initial presentation of lung cancer in the emergency department: a descriptive analysis. CMAJ Open 7(1):E117–E123. https://doi.org/10.9778/cmajo.20180061

Weithorn D, Arientyl V, Solsky I et al (2020) Diagnosis setting and colorectal cancer outcomes: the impact of cancer diagnosis in the emergency department. J Surg Res 255:164–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2020.05.005

Rogers MJ, Matheson LM, Garrard B et al (2016) Cancer diagnosed in the Emergency Department of a Regional Health Service. Aust J Rural Health 24(6):409–414. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajr.12280

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). The opinions, results and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement of ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred. These datasets were linked using unique encoded identifiers and analyzed at ICES. Parts of this material are based on data and/or information compiled and provided by the Canadian Institutes of Health Information (CIHI). However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed in the material are those of the authors, and not necessarily those of CIHI. Parts of this material are based on the data and information provided by Cancer Care Ontario (CCO) and the Government of Canada (Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada’s Permanent Residence Database). The opinions, results, view and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of CCO or the Government of Canada. No endorsement by CCO or the Government of Canada is intended or should be inferred.

Funding

This study was funded by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and a Grant from Cancer Care Ontario.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors decalre that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

ICES is a prescribed entity under section 45 of Ontario’s Personal Health Information Protection Act. Section 45 authorizes ICES to collect personal health information, without consent, for the purpose of analysis or compiling statistical information with respect to the management of, evaluation or monitoring of, the allocation of resources to or planning for all or part of the health system. Projects conducted under section 45, by definition, do not require review by a Research Ethics Board. This project was conducted under section 45, and approved by ICES’ Privacy and Legal Office.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Webber, C., Whitehead, M., Eisen, A. et al. Factors associated with waiting time to breast cancer diagnosis among symptomatic breast cancer patients: a population-based study from Ontario, Canada. Breast Cancer Res Treat 187, 225–235 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-020-06051-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-020-06051-0