Abstract

Purpose

In the phase II DIRECT study a fasting mimicking diet (FMD) improved the clinical response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy as compared to a regular diet. Quality of Life (QoL) and illness perceptions regarding the possible side effects of chemotherapy and the FMD were secondary outcomes of the trial.

Methods

131 patients with HER2-negative stage II/III breast cancer were recruited, of whom 129 were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive either a fasting mimicking diet (FMD) or their regular diet for 3 days prior to and the day of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) questionnaires EORTC-QLQ-C30 and EORTC-QLQ-BR23; the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (BIPQ) and the Distress Thermometer were used to assess these outcomes at baseline, halfway chemotherapy, before the last cycle of chemotherapy and 6 months after surgery.

Results

Overall QoL and distress scores declined during treatment in both arms and returned to baseline values 6 months after surgery. However, patients’ perceptions differed slightly over time. In particular, patients receiving the FMD were less concerned and had better understanding of the possible adverse effects of their treatment in comparison with patients on a regular diet. Per-protocol analyses yielded better emotional, physical, role, cognitive and social functioning scores as well as lower fatigue, nausea and insomnia symptom scores for patients adherent to the FMD in comparison with non-adherent patients and patients on their regular diet.

Conclusions

FMD as an adjunct to neoadjuvant chemotherapy appears to improve certain QoL and illness perception domains in patients with HER2-negative breast cancer.

Trialregister

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02126449.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Short-term fasting (STF) during cancer treatment has attracted increasing attention since the first report of benefits in mice in 2008 [1]. Indeed, in rodents, fasting limits tumor proliferation and enhances the sensitivity of tumor cells to cancer therapies, while simultaneously protecting healthy cells against its toxic effects [2,3,4]. These experimental benefits triggered a number of small clinical trials exploring the potential of STF during cancer treatment [5, 6], which suggested similar effects in humans.

Water-only fasting is difficult to sustain and may have adverse effects associated with energy- and/or micronutrient deficiencies. Fasting mimicking diets (FMD) are designed to mimic the physiologic effects of water-only fasting, while offering minimally required (micro)nutrients [4, 7]. These diets are plant-based and primarily comprise complex carbohydrates and healthy fats, while simple carbohydrates are virtually absent and protein content is low. We recently reported that an FMD, as compared to regular diet, enhanced the radiological as well as the pathological tumor response to chemotherapy in women with HER2-negative breast cancer [8]. Despite omitting dexamethasone prior to chemotherapy in the FMD arm, grade III/IV toxicity was similar in both study arms and chemotherapy-induced DNA damage in lymphocytes was less in patients receiving the FMD, suggesting that the diet simultaneously limits adverse effects in healthy cells.

Cancer, as well as its treatment, significantly reduces the quality of life QoL of patients [9, 10]. Individuals construct cognitive and emotional representations of an illness (i.e., illness perceptions) as an adaptive mechanism [11]. Illness perceptions can be used to explain behavior following heart attacks, the response to cancer screening or how patients cope with cancer treatment [12]. The Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (BIPQ) is a validated, widely used instrument to assess patients’ cognitions and emotions about an illness, a received or proposed treatment or future perspectives [12]. Negative illness perceptions in patients with cancer, or other chronic diseases, have been associated with worse health outcomes, such as higher mortality rates, more severe symptom burden and poorer treatment adherence [13,14,15,16]. Furthermore, patients with cancer and negative illness perceptions have been reported to experience lower quality of life and more physical distress [17,18,19].

It is unknown if STF or FMDs affect cancer patients’ QoL and illness perceptions. Previous studies suggest that STF is safe, well tolerated, and perhaps even associated with improved QoL [20,21,22]. Indeed, QoL increased without any serious side effect in more than 2000 subjects with chronic illness and pain syndromes, who used a very low-calorie diet of 350 kcal per day for 7 days [23]. A small randomized cross-over trial with 34 patients evaluated the effect of STF on QoL in patients with breast cancer and ovarian cancer treated with chemotherapy. STF enhanced tolerance to chemotherapy, while QoL was less compromised and fatigue was reduced [22]. Little data is available about patients’ motivations and perceptions of fasting during cancer treatment. Interviews conducted in a group of 16 patients with breast cancer showed that fasting gave them a greater sense of control over their treatment [24]. If patients are randomized to receive an FMD they can contribute personally to their treatment. This may lead to more active involvement and different illness perceptions regarding treatment and its possible side effects.

The multicenter, open label, phase II randomized DIRECT study was conducted to evaluate the impact of an FMD on toxicity as well as on the response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with HER2-negative breast cancer [8]. QoL and illness perceptions regarding the possible side effects of chemotherapy and the FMD were secondary outcomes of the DIRECT trial. Our hypothesis is that patients on an FMD would experience less toxic side effects from their treatment, resulting in better QoL, less distress and more positive perceptions towards possible side effects, compared to patients on a regular diet.

Methods

Study design and treatment

The detailed study design has been previously reported in Nature Communications [8]. In brief, the DIRECT trial was a multicenter, open label, phase II trial randomizing between an FMD or regular diet for 3 days prior to and the day of neoadjuvant chemotherapy and before surgery in women with HER2-negative breast cancer. The FMD is a 4-day plant-based low amino acid substitution diet, consisting of soups, broths, liquids vitamin tablets and tea. Calorie content declined from day 1 (~1200 kcal), to days 2–4 (~200 kcal) (supplementary material). All patients provided informed consent prior to start of chemotherapy and randomization. This study (NCT02126449) was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (October 2013) and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Leiden University Medical Center in agreement with the Dutch law for medical research involving human subjects.

Monitoring adherence

On the day of each cycle of chemotherapy (prior to drug administration), fasting values of glucose, insulin and IGF-1 were determined in plasma for all patients in both study arms and ketone bodies in an urine portion. Also during this visit adherence to FMD or normal diet was noted by the oncologist or research nurse based on self-reports of patients.

Patient-reported quality of life, illness perceptions and burden

Outcomes were assessed at baseline (QoL and Illness Perception), halfway chemotherapy (QoL and Distress), before the last cycle of chemotherapy (QoL, Distress and Illness Perception) and 6 months after surgery (QoL and Distress) to explore long-term effects of the intervention. The amount of distress caused by treatment was not measured at baseline, since patients had not receive treatment at that time.

Quality of life

Global QoL, functioning and symptoms were assessed with the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer QoL Questionnaire Core 30 (EORTC-QLQ-C30) and Breast Cancer Questionnaire (QLQ-BR23). The EORTC-QLQ-C30 includes 30 items covering five functional scales; ten symptom scales or single items and one global health status scale [25]. The EORTC-QLQ-BR23 collects disease-specific data. It comprises 23 items, divided into four functioning scales and four symptom scales. This questionnaire is widely used to assess breast cancer-related problems [26]. The items covering “breast symptoms and arm symptoms” were excluded in our study, as the trial concerned neoadjuvant therapy and patients did not have surgery yet.

In accordance with the scoring manual linear transformed scores were computed for the QLQ-C30 and QLQ-BR23 scales for each assessment time point [27]. Differences of at least 10 points on the scales/items were defined as the threshold for minimum of clinically significant difference [28].

Distress

Patients were asked to rate their overall distress caused by their treatment on a visual analog scale (a thermometer). The Distress Thermometer (DT) is developed and validated for evaluation of distress in patients with cancer [29]. The DT is a single-item instrument that relates to the level of distress (range 0–10) a patient has experienced in the past week. A score of ≥5 was the cut-off for clinically relevant distress, based on a Dutch validation study [29].

Illness perception

Illness perceptions about the possible side effects of chemotherapy and effectiveness of an FMD were assessed with the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (BIPQ). The BIPQ consists of eight questions that measure eight dimensions of illness perceptions in the following order: Understanding (how well do you feel you understand your illness), Consequences (how much does your illness affect your life), Timeline (how long do you think your illness will last), Personal Control (how much control do you feel you have over your illness), Treatment Control (how much do you think your treatment can help your illness), Identity (how much do you experience symptoms from your illness), Concern (how concerned are you about your illness), and Emotional Representation (how much does your illness affect you emotionally). For this study, the word “illness” was replaced with “possible side effects of chemotherapy” and the word “treatment” was replaced with “a fasting mimicking diet”. Answers were given on a scale ranging from 0 to 10 [30]. Higher scores represent more negative illness perception, except for understanding, personal control and treatment control.

Statistical analyses

The sample size was based on the primary study endpoint of this phase II trial, grade III/IV toxicity. Patients were evaluable for analysis if they completed the set of baseline questionnaires and at least one of the consecutive questionnaires. The questionnaire adherence per cycle was measured as the percentage of patients completing each instrument.

A two-sided Fisher exact rest was used to compare the proportion of adherent patients for each questionnaire between randomization groups. Continuous variables with a normal distribution were expressed as mean value and standard deviation. Comparison of baseline characteristics was performed using the Fisher exact test for categorical variables and the two-tailed Student’s t test for continuous variables. The effect of the FMD on the different QoL scales and distress were estimated using linear mixed models, with an unstructured covariance matrix including treatment, time and the interaction between treatment and time. For each scale, all scores over time were used as the dependent outcome in the models. The baseline measures: clinical stage, hormonal status, body mass index and type of chemotherapy were entered in the model as covariates. With the use of a mixed model, we can deal with correlated structure in the present data, without adjustments for multiple comparisons. Because the measurements of illness perceptions consisted of only two time points, the effect of the FMD on BIPQ scores was estimated with a linear regression model with the same covariates entered in the mixed models. The analyses were performed according to the intention-to-treat principle. A post hoc, exploratory per-protocol analysis was done to explore the effects of the FMD on QoL, distress and illness perceptions. Patients who were adherent to the FMD for at least half of the cycles were compared with those who were less adherent, and with the adherent control patients (i.e., the patients in the control group who did not fast on their own initiative). All tests were 2-tailed with a significance level of 0.05. All data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp).

Results

Patient characteristics

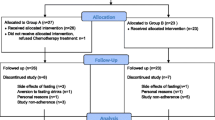

From February 2014 to January 2018, 131 patients from 11 centers from the Dutch Breast Cancer Research Group (BOOG) were randomized. One patient withdrew informed consent before starting with chemotherapy and one patient was ineligible because of liver metastasis, which were diagnosed the day after randomization. Of the remaining 129 patients, 65 received the FMD as an adjunct to the standard chemotherapy and 64 used their regular diet (Fig. 1). Patients’ characteristics were well balanced between the two study arms (Table 1).

Adherence to the FMD

Fifty three out of 65 patients (81.5%) completed the first FMD cycle, whereas over 50% completed at least 2 FMD cycles. 22 out of 65 patients (33.8%) used the FMD for at least four cycles, and 21.5% of the patients adhered to FMD during all cycles of chemotherapy (Table 2). The main reason for non-adherence to the FMD was aversion to distinct components of the diet, perhaps induced by chemotherapy. In the regular diet group, 5 (7.8%) patients did not adhere (they decided to fast during one or more cycles of chemotherapy).

Weight changes

Patients randomized for the FMD displayed a decrease in body mass index (BMI) halfway therapy (median decrease 0.38 kg/m2, range −2.16 to +3.43, P = 0.002) and at the end of therapy (median decrease 0.33 kg/m2, range −2.48 to +4.81, P = 0.026). In the regular diet group BMI at the end of therapy was higher than at baseline (median increase 0.64 kg/m2, range −3.93 to +4.71, P = 0.006). This difference persisted 6 months after surgery (median increase of 0.56 kg/m2, range −2.03 to +6.17, P = 0.043) in patients on a regular diet, whereas the BMI of patients on an FMD did not differ from the BMI before start of chemotherapy.

Completion of questionnaires

Questionnaire set 1 (EORTC-QLQ-C30, EORTC BR23 and the BIPQ) was completed by 121 patients (94%) before the start of chemotherapy, questionnaire set 2 (EORTC-QLQ-C30, EORTC BR23 and the DT) was completed by 112 patients (87%) halfway chemotherapy, questionnaire set 3 (EORTC-QLQ-C30, EORTC BR23, DT and the BIPQ) was completed by 87 patients (67%) before the last cycle of chemotherapy and questionnaire set 4 (EORTC-QLQ-C30, EORTC BR23 and the DT) was completed by 100 patients (78%) 6 months after surgery. Non-response to the third set of questionnaires occurred more frequently in the FMD arm (41% vs. 23%, p < 0.05).

Quality of life

The mean baseline overall QLQ‐C30 and QLQ‐BR23 scale scores were similar in both treatment groups (Table 3). Scores deteriorated similarly during chemotherapy in both study arms and returned to baseline values during follow-up. Figures 2a–n, 3a–f and Table 4 present QoL scores over time in both groups.

a–o Mean changes from baseline on functional and symptom scales of the EORTC-QLQ-C30. These plots show mean changes and 95% CIs calculated from the raw data; they are not model estimates, and they are not adjusted for any covariates. CT chemotherapy, FMD fasting mimicking diet, CI confidence interval. Lower scores on the functional scales (a–f) implicates lower quality of life, lower scores on the symptom scales (g–o) implicate better quality of life

a–f Mean scores on functional and symptom scales of the EORTC-QLQ-BR23. These plots show mean scores and 95% CIs calculated from the raw data; they are not model estimates, and they are not adjusted for any covariates. Lower scores on the functional scales (a–d) implicates lower quality of life, lower scores on the symptom scales (e, f) implicate better quality of life. CT chemotherapy, FMD fasting mimicking diet, CI confidence interval

Global health status

During treatment, the global health status scale deteriorated significantly in both study arms (p < 0.01) (Fig. 2a) and returned to baseline at follow-up (6 months after surgery). Similar patterns were observed in the per-protocol analysis, without any difference between adherent and non-adherent patients (supplementary material).

Functional scales of the QLQ-C30

Physical, role, and cognitive functioning scores declined clinically and statistically significantly in both arms during treatment (p < 0.01), with the lowest scores at the end of chemotherapy (Fig. 2b–f). Deterioration of social functioning was statistically significant, but not clinically relevant in either group (a decrease in score of <10; Fig. 2f). Patients reported significant improvement of emotional functioning in both arms over time (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2d). In the per-protocol analyses, better scores were observed in all five functional scales (physical, role, emotional, cognitive and social functioning) in patients adherent to the FMD in comparison with non-adherent patients and patients on a regular diet (supplementary material).

Symptom scales of the QLQ-C30

In both arms, patients reported clinically relevant and significant worsening of fatigue, pain, dyspnea, loss of appetite and constipation in the course of treatment (p < 0.01) (Fig. 2g–o). Patients following the FMD tended to have better scores on insomnia (Fig. 2k, p = 0.068). In both groups, patients reported significant worsening of nausea in the course of treatment, but in the FMD group the difference was not clinically relevant (an increase in nausea score of <10; Fig. 2h). Per-protocol analyses revealed that patients who were adherent to the diet reported less complaints of fatigue, nausea and insomnia. There were no differences in the other symptom scales between adherent and non-adherent FMD patients or patients on a regular diet (supplementary material).

Functional scales of the QLQ-BR23

There were no differences between groups over time in the functional scales body image, sexual functioning and future perspective. Patients on a regular diet reported better scores on sexual enjoyment at the last time point, whereas patients on the FMD did not fully recover to baseline values (p = 0.040). In both arms, patients reported lower scores on body image, sexual functioning and sexual enjoyment during treatment (Fig. 3a–d). Per-protocol analyses did not show any differences between groups (supplementary material).

QLQ-BR23 symptom scales

The side effects of chemotherapy and hair loss scores worsened in both arms during treatment (Fig. 3e, f). There were no differences between groups in intention-to-treat or per-protocol analyses (supplementary material).

Distress

The mean Distress Thermometer (DT) score halfway chemotherapy for all patients was 5.19 (SD = 2.1), with a range of 1–10. 61.3% of the patients experienced clinically relevant distress (DT score ≥5). During treatment and at 6-month follow-up, clinically relevant distress gradually increased in both groups to 78.0% and 70.7% of control and FMD patients, respectively (Fig. 4). There were no differences between groups in scores at the 3 time points, or over time (Table 4). The per-protocol analyses yielded similar results and did not uncover differences between groups over time (supplementary material).

Illness perception

At baseline, there were no different perceptions of the possible side effects of their treatment between groups (Table 3). Patients believed to have personal control over the possible side effects, were positive about the effectiveness of their treatment and felt they had a good understanding of potential adverse effects. At the end of chemotherapy FMD patients reported numerically but not statistically significant more positive outcomes of almost every perception, with the greatest improvement of concerns and emotional response (Fig. 5a–h; Table 5). In comparison with controls, FMD patients felt they had better understanding of side effects (p ≤ 0.01), and they were less concerned about them over time (p < 0.05, Table 5). In both groups, patients reported to believe they had less personal control over their side effects in the course of treatment (Fig. 5d). In the per-protocol analyses more positive perceptions of understanding, consequences (how much the side effects affect their life) and identity (how much side effects they experience) were observed in patients adherent to the FMD in comparison with patients on a regular diet (supplementary material).

Discussion

The randomized, phase 2 DIRECT trial demonstrated no impact of an FMD as compared with a regular diet on grade III/IV toxicity, as documented by a physician and graded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.03, during neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with HER2-negative breast cancer [8]. The current analysis indicates that, patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) were distinct in some respects between groups. Our data suggest that the FMD was associated with increased overall well-being from a patients’ perspective. A per-protocol analysis, yielding better scores of various aspects of QoL in patients who were adherent to the diet than in those who were not, or in controls, supports this inference.

As expected, neoadjuvant chemotherapy was accompanied by the occurrence of side effects, impaired QoL and distress, with recovery of most of the scores after 6 months of follow-up. This is in line with previous studies of patients with breast cancer receiving anthracycline- and taxane-based regimens of chemotherapy [9, 10, 31, 32]. The mean baseline EORTC-QLQ-C30 and QLQ-BR23 scores of patients in our study were largely similar to the reference values for patients with early stage breast cancer [33]. Also, the illness perceptions before the start of chemotherapy were quite similar to those reported in other patients with breast cancer [34], although the perception of personal control in our study seemed slightly stronger than usually reported. Perhaps patients who gave informed consent for the trial became convinced that an FMD could ameliorate the side effects of chemotherapy after reading the study information.

FMD patients did not score worse than controls on any of the subscales of the EORTC-QLQ-C30, the QLQ-BR23, or the distress thermometer. In fact, post hoc analyses revealed that patients who were adherent to the diet (at least half of the cycles of chemotherapy) had favorable outcomes regarding physical, role, emotional, cognitive and social functioning, and had fewer complaints of fatigue, nausea and insomnia than non-adherent patients or controls. These positive effects of the FMD are in line with other trials and animal studies, in which STF and FMD enhanced cognitive performance [7], improved QoL [22, 35] and reduced fatigue [22] in patients with cancer and people with the metabolic syndrome. In addition to metabolic benefits, the periodic fasting mimicking diet seems to have beneficial effects on patients’ overall well-being and functioning in daily life.

Although the effects of fasting on treatment with chemotherapy in patients with cancer are currently uncertain, promising results of preclinical and clinical studies, extensively covered by the media, spurred enthusiasm for fasting among patients with cancer [24]. Fasting made people feel more proactively involved in treatment and recovery [24]. We did not observe such differences in our illness perception measures, as both treatment groups were positive about their personal control and the effectiveness of their treatment. We did find that FMD patients had better understanding and were less concerned about the possible side effects in the course of their treatment. A meta-analysis of the BIPQ showed associations between negative concern perceptions and lower scores on QoL assessments on psychological, physical and fatigue domains [12]. The results of our per-protocol analysis with more positive outcomes on similar QoL domains in patients adherent to the FMD are in line with this finding.

In general, patients with breast cancer gain weight during chemotherapy, which often persists in the years following completion of treatment [36,37,38]. Weight gain can lead to poor QoL, physiological stress and body image issues [39, 40]. Reduction in physical activity, dietary changes, the use of steroids as anti-emetics, and therapy-induced menopause all contribute to weight gain during breast cancer treatment. In our trial, patients in the FMD group were not prescribed dexamethasone prior to AC/FEC, because we previously found that this prevents the decline of glucose and insulin in response to the diet [41]. Although patients were not allowed to lose more than 10% of bodyweight during the trial, patients using the FMD had a moderate decrease in body mass index (BMI) during the course of treatment, which was not seen in patients on a regular diet. At 6 months of follow-up patients on the FMD had maintained their normal weight, while patients who followed their regular diet displayed an increase in BMI. Thus, an FMD may offer protection against the common weight gain during and after treatment with chemotherapy in patients with breast cancer.

This study has some limitations. Although the percentage of returned questionnaires was high, questionnaire completion declined in the course of the trial period, and completion rates differed between groups. In particular, patients who were non-adherent to the FMD more often failed to fill out the last two questionnaires. This might provide biased results, as it is conceivable that patients who stopped the FMD because of side effects would have reported lower scores on QoL as well. Furthermore, the lack of blinding, which is obviously very difficult in any nutrition trial, may have affected patients ‘behavior and perceptions. Finally, it is important to point out that the results of our per-protocol analyses should be cautiously interpreted. In particular, it is conceivable that patients who felt better for any reason were more inclined to stick to their dietary prescriptions, which would dismiss the putative benefits of the FMD for well-being, in defiance of the myriad indications to the contrary in previous studies [7, 22, 35].

To our knowledge, this is the first large randomized trial assessing the effect of an FMD on QoL in patients with breast cancer. Our results need to be confirmed in other trials, which are currently ongoing. Furthermore, we plan to do more research to improve adherence to short-term fasting and FMDs, using revised diets.

In conclusion, our study suggests that an FMD as an adjunct to neoadjuvant chemotherapy may have beneficial effects on certain QoL and illness perceptions domains in patients with HER2-negative breast cancer, which is in line with previous reports on clinical response and safety.

References

Raffaghello L, Lee C, Safdie FM, Wei M, Madia F, Bianchi G et al (2008) Starvation-dependent differential stress resistance protects normal but not cancer cells against high-dose chemotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105(24):8215–8220

Lv M, Zhu X, Wang H, Wang F, Guan W (2014) Roles of caloric restriction, ketogenic diet and intermittent fasting during initiation, progression and metastasis of cancer in animal models: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 9(12):e115147

De Lorenzo MS, Baljinnyam E, Vatner DE, Abarzua P, Vatner SF, Rabson AB (2011) Caloric restriction reduces growth of mammary tumors and metastases. Carcinogenesis 32(9):1381–1387

Nencioni A, Caffa I, Cortellino S, Longo VD (2018) Fasting and cancer: molecular mechanisms and clinical application. Nat Rev Cancer 18(11):707–719

de Groot S, Pijl H, van der Hoeven JJM, Kroep JR (2019) Effects of short-term fasting on cancer treatment. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 38(1):209

Safdie FM, Dorff T, Quinn D, Fontana L, Wei M, Lee C et al (2009) Fasting and cancer treatment in humans: a case series report. Aging (Albany NY) 1(12):988–1007

Brandhorst S, Choi IY, Wei M, Cheng CW, Sedrakyan S, Navarrete G et al (2015) A periodic diet that mimics fasting promotes multi-system regeneration, enhanced cognitive performance, and healthspan. Cell Metab 22(1):86–99

de Groot S, Lugtenberg RT, Cohen D, Welters MJP, Ehsan I, Vreeswijk MPG et al (2020) Fasting mimicking diet as an adjunct to neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer in the multicentre randomized phase 2 DIRECT trial. Nat Commun 11(1):3083

Hall E, Cameron D, Waters R, Barrett-Lee P, Ellis P, Russell S et al (2014) Comparison of patient reported quality of life and impact of treatment side effects experienced with a taxane-containing regimen and standard anthracycline based chemotherapy for early breast cancer: 6 year results from the UK TACT trial (CRUK/01/001). Eur J Cancer (Oxford, England: 1990) 50(14):2375–2389

Brandberg Y, Johansson H, Hellstrom M, Gnant M, Mobus V, Greil R et al (2020) Long-term (up to 16 months) health-related quality of life after adjuvant tailored dose-dense chemotherapy vs. standard three-weekly chemotherapy in women with high-risk early breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 181(1):87–96

Thong MSY, Mols F, Kaptein AA, Boll D, Vos C, Pijnenborg JMA et al (2019) Illness perceptions are associated with higher health care use in survivors of endometrial cancer-a study from the population-based PROFILES registry. Support Care Cancer Off J Multinat Assoc Support Care Cancer 27(5):1935–1944

Broadbent E, Wilkes C, Koschwanez H, Weinman J, Norton S, Petrie KJ (2015) A systematic review and meta-analysis of the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire. Psychol Health 30(11):1361–1385

Thong MS, Kaptein AA, Vissers PA, Vreugdenhil G, van de Poll-Franse LV (2016) Illness perceptions are associated with mortality among 1552 colorectal cancer survivors: a study from the population-based PROFILES registry. J Cancer Surviv 10(5):898–905

Iskandarsyah A, de Klerk C, Suardi DR, Sadarjoen SS, Passchier J (2014) Consulting a traditional healer and negative illness perceptions are associated with non-adherence to treatment in Indonesian women with breast cancer. Psychooncology 23(10):1118–1124

Thune-Boyle IC, Myers LB, Newman SP (2006) The role of illness beliefs, treatment beliefs, and perceived severity of symptoms in explaining distress in cancer patients during chemotherapy treatment. Behav Med 32(1):19–29

Crawshaw J, Rimington H, Weinman J, Chilcot J (2015) Illness perception profiles and their association with 10-year survival following cardiac valve replacement. Ann Behav Med 49(5):769–775

Gray NM, Hall SJ, Browne S, Johnston M, Lee AJ, Macleod U et al (2014) Predictors of anxiety and depression in people with colorectal cancer. Support Care Cancer Off J Multinat Assoc Support Care Cancer 22(2):307–314

Ashley L, Marti J, Jones H, Velikova G, Wright P (2015) Illness perceptions within 6 months of cancer diagnosis are an independent prospective predictor of health-related quality of life 15 months post-diagnosis. Psychooncology 24(11):1463–1470

Fischer MJ, Inoue K, Matsuda A, Kroep JR, Nagai S, Tozuka K et al (2017) Cross-cultural comparison of breast cancer patients’ Quality of Life in the Netherlands and Japan. Breast Cancer Res Treat 166(2):459–471

Wilhelmi de Toledo F, Grundler F, Bergouignan A, Drinda S, Michalsen A (2019) Safety, health improvement and well-being during a 4 to 21-day fasting period in an observational study including 1422 subjects. PLoS One. 14(1):e0209353

Fond G, Macgregor A, Leboyer M, Michalsen A (2013) Fasting in mood disorders: neurobiology and effectiveness. A review of the literature. Psychiatry Res 209(3):253–258

Bauersfeld SP, Kessler CS, Wischnewsky M, Jaensch A, Steckhan N, Stange R et al (2018) The effects of short-term fasting on quality of life and tolerance to chemotherapy in patients with breast and ovarian cancer: a randomized cross-over pilot study. BMC Cancer 18(1):476

Michalsen A, Hoffmann B, Moebus S, Backer M, Langhorst J, Dobos GJ (2005) Incorporation of fasting therapy in an integrative medicine ward: evaluation of outcome, safety, and effects on lifestyle adherence in a large prospective cohort study. J Alternat Complement Med (New York, NY) 11(4):601–607

Mas S, Le Bonniec A, Cousson-Gelie F (2019) Why do women fast during breast cancer chemotherapy? A qualitative study of the patient experience. Br J Health Psychol 24(2):381–395

Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ et al (1993) The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 85(5):365–376

Sprangers MA, Groenvold M, Arraras JI, Franklin J, te Velde A, Muller M et al (1996) The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer breast cancer-specific quality-of-life questionnaire module: first results from a three-country field study. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 14(10):2756–2768

Fayers PM (1995) EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual: European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. Available from: https://abdn.pure.elsevier.com/en/publications/eortc-qlqc30-scoring-manual-2. Accessed 17 Apr 2020

Cocks K, King MT, Velikova G, de Castro G, Jr., Martyn St-James M, Fayers PM et al (2012) Evidence-based guidelines for interpreting change scores for the European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30. Eur J Cancer (Oxford, England: 1990) 48(11):1713–1721

Tuinman MA, Gazendam-Donofrio SM, Hoekstra-Weebers JE (2008) Screening and referral for psychosocial distress in oncologic practice: use of the distress thermometer. Cancer 113(4):870–878

Broadbent E, Petrie KJ, Main J, Weinman J (2006) The brief illness perception questionnaire. J Psychosom Res 60(6):631–637

Nyrop KA, Deal AM, Shachar SS, Basch E, Reeve BB, Choi SK et al (2019) Patient-reported toxicities during chemotherapy regimens in current clinical practice for early breast cancer. Oncologist 24(6):762–771

Zaheed M, Wilcken N, Willson ML, O'Connell DL, Goodwin A (2019) Sequencing of anthracyclines and taxanes in neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy for early breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2:Cd012873

Scott NW, Fayers PM, Aaronson NK, Graeff A De, Groenvold M, Koller M et al (2008) EORTC QLQ-C30 reference values

Kaptein AA, Schoones JW, Fischer MJ, Thong MS, Kroep JR, van der Hoeven KJ (2015) Illness perceptions in women with breast cancer—a systematic literature Review. Curr Breast Cancer Rep 7(3):117–126

Michalsen A, Hoffmann B, Moebus S, Bäcker M, Langhorst J, Dobos GJ (2005) Incorporation of fasting therapy in an integrative medicine ward: evaluation of outcome, safety, and effects on lifestyle adherence in a large prospective cohort study. J Altern Complement Med (New York, NY) 11(4):601–607

Kwok A, Palermo C, Boltong A (2015) Dietary experiences and support needs of women who gain weight following chemotherapy for breast cancer. Support Care Cancer Off J Multinatl Assoc Support Care Cancer 23(6):1561–1568

Saquib N, Flatt SW, Natarajan L, Thomson CA, Bardwell WA, Caan B et al (2007) Weight gain and recovery of pre-cancer weight after breast cancer treatments: evidence from the women’s healthy eating and living (WHEL) study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 105(2):177–186

Basen-Engquist KM, Raber M, Carmack CL, Arun B, Brewster AM, Fingeret M et al (2020) Feasibility and efficacy of a weight gain prevention intervention for breast cancer patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy: a randomized controlled pilot study. Support Care Cancer Off J Multinatl Assoc Support Care Cancer

Di Meglio A, Michiels S, Jones LW, El-Mouhebb M, Ferreira AR, Martin E et al (2020) Changes in weight, physical and psychosocial patient-reported outcomes among obese women receiving treatment for early-stage breast cancer: a nationwide clinical study. Breast 52:23–32

Imayama I, Alfano CM, Neuhouser ML, George SM, Wilder Smith A, Baumgartner RN et al (2013) Weight, inflammation, cancer-related symptoms and health related quality of life among breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat 140(1):159–176

de Groot S, Vreeswijk MP, Welters MJ, Gravesteijn G, Boei JJ, Jochems A et al (2015) The effects of short-term fasting on tolerance to (neo) adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-negative breast cancer patients: a randomized pilot study. BMC cancer 15:652

Acknowledgements

We are greatly indebted to the patients for participating in this study, and their physicians for including the patients: E. Goker (Alexander Monro Hospital), A.J.M. Pas (‘t Langeland Hospital) A.H. Honkoop (Isala). We thank Wil Planje of the Clinical Research Center for logistics of the questionnaires.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from Pink Ribbon (2012.WO31.C155) and Amgen (20139098).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

JRK, HP, JJMH, SdG, AAK, MF and VDL contributed to study concept/design. JRK, SdG, DC, HdG, JBH, JEAP, AJvdW, ALTI, LWK, SV, AB, EMKK, MDC and RTL contributed to data acquisition. SdG, MF and RTL contributed to statistical analysis. RTL, HP, JRK, SdG and AAK contributed to manuscript preparation. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

V.D. Longo has equity interest in L-Nutra. H. Pijl has shares in a company that invested in L-Nutra. No conflicts of interest were disclosed by the other authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lugtenberg, R.T., de Groot, S., Kaptein, A.A. et al. Quality of life and illness perceptions in patients with breast cancer using a fasting mimicking diet as an adjunct to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in the phase 2 DIRECT (BOOG 2013–14) trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat 185, 741–758 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-020-05991-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-020-05991-x