Abstract

Purpose

Accurate risk assessment is necessary for decision-making around breast cancer prevention. We aimed to develop a breast cancer prediction model for postmenopausal women that would take into account their individualized competing risk of non-breast cancer death.

Methods

We included 73,066 women who completed the 2004 Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) questionnaire (all ≥57 years) and followed participants until May 2014. We considered 17 breast cancer risk factors (health behaviors, demographics, family history, reproductive factors) and 7 risk factors for non-breast cancer death (comorbidities, functional dependency) and mammography use. We used competing risk regression to identify factors independently associated with breast cancer. We validated the final model by examining calibration (expected-to-observed ratio of breast cancer incidence, E/O) and discrimination (c-statistic) using 74,887 subjects from the Women’s Health Initiative Extension Study (WHI-ES; all were ≥55 years and followed for 5 years).

Results

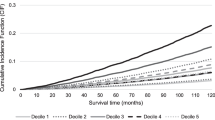

Within 5 years, 1.8 % of NHS participants were diagnosed with breast cancer (vs. 2.0 % in WHI-ES, p = 0.02), and 6.6 % experienced non-breast cancer death (vs. 5.2 % in WHI-ES, p < 0.001). Using a model selection procedure which incorporated the Akaike Information Criterion, c-statistic, statistical significance, and clinical judgement, our final model included 9 breast cancer risk factors, 5 comorbidities, functional dependency, and mammography use. The model’s c-statistic was 0.61 (95 % CI [0.60–0.63]) in NHS and 0.57 (0.55–0.58) in WHI-ES. On average, our model under predicted breast cancer in WHI-ES (E/O 0.92 [0.88–0.97]).

Conclusions

We developed a novel prediction model that factors in postmenopausal women’s individualized competing risks of non-breast cancer death when estimating breast cancer risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- AIC:

-

Akaike information criterion

- BCRAT:

-

Breast cancer risk assessment tool

- BCSC:

-

Breast cancer surveillance consortium model

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CRR:

-

Competing risk regression

- E/O:

-

Expected-to-observed ratio

- MI:

-

Myocardial infarction

- NHS:

-

Nurses’ health study

- PHR:

-

Proportional hazards regression

- SEER:

-

Surveillance epidemiology and end results

- WHI:

-

Women’s health initiative study

- WHI-CT:

-

Women’s health initiative clinical trials

- WHI-ES:

-

Women’s health initiative extension study

- WHI-OS:

-

Women’s health initiative observational study

References

Walter LC, Schonberg MA (2014) Screening mammography in older women: a review. JAMA 311(13):1336–1347

Nelson HD, Smith ME, Griffin JC, Fu R (2013) Use of medications to reduce risk for primary breast cancer: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 158(8):604–614

Gail MH, Brinton LA, Byar DP, Corle DK, Green SB, Schairer C, Mulvihill JJ (1989) Projecting individualized probabilities of developing breast cancer for white females who are being examined annually. J Natl Cancer Inst 81(24):1879–1886

Tyrer J, Duffy SW, Cuzick J (2004) A breast cancer prediction model incorporating familial and personal risk factors. Stat Med 23(7):1111–1130

Tice JA, Cummings SR, Smith-Bindman R, Ichikawa L, Barlow WE, Kerlikowske K (2008) Using clinical factors and mammographic breast density to estimate breast cancer risk: development and validation of a new predictive model. Ann Int Med 148(5):337–347

Yourman LC, Lee SJ, Schonberg MA, Widera EW, Smith AK (2012) Prognostic indices for older adults: a systematic review. JAMA 307(2):182–192

Fine JP, Gray RJ (1999) A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 94:496–509

Berry SD, Ngo L, Samelson EJ, Kiel DP (2010) Competing risk of death: an important consideration in studies of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 58(4):783–787

Gooley TA, Leisenring W, Crowley J, Storer BE (1999) Estimation of failure probabilities in the presence of competing risks: new representations of old estimators. Stat Med 18(6):695–706

Pepe MS, Mori M (1993) Kaplan-Meier, marginal or conditional probability curves in summarizing competing risks failure time data? Stat Med 12(8):737–751

Liu Y, McCarthy EP, Ngo LH (2015) Predicting breast cancer mortality in the presence of competing risks using smartphone application development software. Int J Stat Med Res 4:322–330

de Glas NA, Kiderlen M, Vandenbroucke JP, de Craen AJ, Portielje JE, van de Velde CJ, Liefers GJ, Bastiaannet E, Le Cessie S (2016) Performing survival analyses in the presence of competing risks: a clinical example in older breast cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst 108(5):djv366

Colditz GA, Manson JE, Hankinson SE (1997) The Nurses’ Health Study: 20-year contribution to the understanding of health among women. J Womens Health 6(1):49–62

Colditz GA, Martin P, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Sampson L, Rosner B, Hennekens CH, Speizer FE (1986) Validation of questionnaire information on risk factors and disease outcomes in a prospective cohort study of women. Am J Epidemiol 123(5):894–900

Newcomb PA, Trentham-Dietz A, Egan KM, Titus-Ernstoff L, Baron JA, Storer BE, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ (2001) Fracture history and risk of breast and endometrial cancer. Am J Epidemiol 153(11):1071–1078

Huang Z, Hankinson SE, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Hunter DJ, Manson JE, Hennekens CH, Rosner B, Speizer FE, Willett WC (1997) Dual effects of weight and weight gain on breast cancer risk. JAMA 278(17):1407–1411

Neuhouser ML, Aragaki AK, Prentice RL, Manson JE, Chlebowski R, Carty CL, Ochs-Balcom HM, Thomson CA, Caan BJ, Tinker LF et al (2015) Overweight, obesity, and postmenopausal invasive breast cancer risk: a secondary analysis of the women’s health initiative randomized clinical trials. JAMA Oncol 1(5):611–621

Cook NR, Rosner BA, Hankinson SE, Colditz GA (2009) Mammographic screening and risk factors for breast cancer. Am J Epidemiol 170(11):1422–1432

Charlson ME, Ales KL, Simon R, MacKenzie CR (1987) Why predictive indexes perform less well in validation studies. Is it magic or methods? Arch Intern Med 147(12):2155–2161

Chaudhry S, Jin L, Meltzer D (2005) Use of a self-report-generated Charlson Comorbidity Index for predicting mortality. Med Care 43(6):607–615

Schonberg MA, Davis RB, McCarthy EP, Marcantonio ER (2009) Index to predict 5-year mortality of community-dwelling adults aged 65 and older using data from the National Health Interview Survey. J Gen Intern Med 24(10):1115–1122

Lee SJ, Lindquist K, Segal MR, Covinsky KE (2006) Development and validation of a prognostic index for 4-year mortality in older adults. JAMA 295(7):801–808

deLeeuw J (1992) Introduction to Akaike (1973) information theory and an extension of the maximum likelihood principle (PDF). In: Kotz S, Johnson NL (eds) Breakthroughs in statistics I. Springer, New York, pp 599–609

Justice AC, Covinsky KE, Berlin JA (1999) Assessing the generalizability of prognostic information. Ann Int Med 130(6):515–524

Daly L (1992) Simple SAS macros for the calculation of exact binomial and Poisson confidence limits. Comput Biol Med 22(5):351–361

Statisical methods in diagnostic medicine using SAS software. http://www2.sas.com/proceedings/sugi30/211-30.pdf. Accessed June 15 2016

Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB (2004) Overall C as a measure of discrimination in survival analysis: model specific population value and confidence interval estimation. Stat Med 23(13):2109–2123

Harrell FE, Lee KL, Mark DB (1996) Tutorial in biostatistics multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med 15:361–387

Schonberg MA, Li VW, Eliassen AH, Davis RB, LaCroix AZ, McCarthy EP, Rosner BA, Chlebowski RT, Rohan TE, Hankinson SE et al. (2016) Performance of the breast cancer risk assessment tool among women age 75 years and older. J Natl Cancer Inst 108(3):djv348

Sweeney C, Blair CK, Anderson KE, Lazovich D, Folsom AR (2004) Risk factors for breast cancer in elderly women. Am J Epidemiol 160(9):868–875

Shantakumar S, Terry MB, Teitelbaum SL, Britton JA, Millikan RC, Moorman PG, Neugut AI, Gammon MD (2007) Reproductive factors and breast cancer risk among older women. Breast Cancer Res Treat 102(3):365–374

Luo J, Margolis KL, Wactawski-Wende J, Horn K, Messina C, Stefanick ML, Tindle HA, Tong E, Rohan TE (2011) Association of active and passive smoking with risk of breast cancer among postmenopausal women: a prospective cohort study. BMJ 342:d1016

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (2009) Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Int Med 151(10):716–726, W-236

Royce TJ, Hendrix LH, Stokes WA, Allen IM, Chen RC (2014) Cancer screening rates in individuals with different life expectancies. JAMA Int Med 174(10):1558–1565

WHI Protocols and Study Consents. https://www.whi.org/researchers/studydoc/SitePages/Protocol%20and%20Consents.aspx. Accessed June 18 2016

Beral V, Reeves G, Bull D, Green J (2011) Breast cancer risk in relation to the interval between menopause and starting hormone therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst 103(4):296–305

Fournier A, Mesrine S, Dossus L, Boutron-Ruault MC, Clavel-Chapelon F, Chabbert-Buffet N (2014) Risk of breast cancer after stopping menopausal hormone therapy in the E3 N cohort. Breast Cancer Res Treat 145(2):535–543

Anderson GL, Chlebowski RT, Aragaki AK, Kuller LH, Manson JE, Gass M, Bluhm E, Connelly S, Hubbell FA, Lane D et al (2012) Conjugated equine oestrogen and breast cancer incidence and mortality in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: extended follow-up of the Women’s Health Initiative randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 13(5):476–486

Schonfeld SJ, Pee D, Greenlee RT, Hartge P, Lacey JV Jr, Park Y, Schatzkin A, Visvanathan K, Pfeiffer RM (2010) Effect of changing breast cancer incidence rates on the calibration of the Gail model. J Clin Oncol 28(14):2411–2417

Schonberg MA, Davis RB, McCarthy EP, Marcantonio ER (2011) External validation of an index to predict up to 9-year mortality of community-dwelling adults aged 65 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc 59(8):1444–1451

Chlebowski RT, Anderson GL, Lane DS, Aragaki AK, Rohan T, Yasmeen S, Sarto G, Rosenberg CA, Hubbell FA (2007) Predicting risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women by hormone receptor status. J Natl Cancer Inst 99(22):1695–1705

Amir E, Evans DG, Shenton A, Lalloo F, Moran A, Boggis C, Wilson M, Howell A (2003) Evaluation of breast cancer risk assessment packages in the family history evaluation and screening programme. J Med Genet 40(11):807–814

Tice JA, Cummings SR, Ziv E, Kerlikowske K (2005) Mammographic breast density and the Gail model for breast cancer risk prediction in a screening population. Breast Cancer Res Treat 94(2):115–122

Chen J, Pee D, Ayyagari R, Graubard B, Schairer C, Byrne C, Benichou J, Gail MH (2006) Projecting absolute invasive breast cancer risk in white women with a model that includes mammographic density. J Natl Cancer Inst 98(17):1215–1226

What is a standard drink? http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Practitioner/pocketguide/pocket_guide2.htm. Accessed June 15 2016

Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool Source Code. http://www.cancer.gov/bcrisktool/download-source-code.aspx. Accessed June 27 2016

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participants and staff of the Nurses’ Health Study for their valuable contributions as well as the following state cancer registries for their help: AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, DE, FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, IA, KY, LA, ME, MD, MA, MI, NE, NH, NJ, NY, NC, ND, OH, OK, OR, PA, RI, SC, TN, TX, VA, WA, and WY. In addition, this study was approved by the Connecticut Department of Public Health (DPH) Human Investigations Committee. Certain data used in this publication were obtained from the DPH. The WHI program is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services through contracts HHSN268201100046C, HHSN268201100001C, HHSN268201100002C, HHSN268201100003C, HHSN268201100004C, and HHSN271201100004C. We would also like to thank the following WHI INVESTIGATORS for their help with this project: Program Office: (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, Maryland) Jacques Rossouw, Shari Ludlam, Dale Burwen, Joan McGowan, Leslie Ford, and Nancy Geller Clinical Coordinating Center: Clinical Coordinating Center: (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA) Garnet Anderson, Ross Prentice, Andrea LaCroix, and Charles Kooperberg Investigators and Academic Centers: (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) JoAnn E. Manson; (MedStar Health Research Institute/Howard University, Washington, DC) Barbara V. Howard; (Stanford Prevention Research Center, Stanford, CA) Marcia L. Stefanick; (The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH) Rebecca Jackson; (University of Arizona, Tucson/Phoenix, AZ) Cynthia A. Thomson; (University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY) Jean Wactawski-Wende; (University of Florida, Gainesville/Jacksonville, FL) Marian Limacher; (University of Iowa, Iowa City/Davenport, IA) Robert Wallace; (University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA) Lewis Kuller; (Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC) Sally Shumaker We would also like to thank Jonathan Yee for his help with data entry for this manuscript. NOTES: The sponsor had no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, the writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. This work was presented in part at the 9th annual meeting of the Cancer and Primary Care Research International Network April 28th, 2016 in Boston, MA.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health (R01 AG041860), an NHS cohort infrastructure Grant (UM1 CA186107), and an NHS program project Grant (P01 CA87969). The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

The experiments comply with the current US laws.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schonberg, M.A., Li, V.W., Eliassen, A.H. et al. Accounting for individualized competing mortality risks in estimating postmenopausal breast cancer risk. Breast Cancer Res Treat 160, 547–562 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-016-4020-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-016-4020-8