Abstract

The ubiquity and high productivity associated with blooms of colonial Phaeocystis makes it an important contributor to the global carbon cycle. During blooms organic matter that is rich in carbohydrates is produced. We distinguish five different pools of carbohydrates produced by Phaeocystis. Like all plants and algal cells, both solitary and colonial cells produce (1) structural carbohydrates, (hetero) polysaccharides that are mainly part of the cell wall, (2) mono- and oligosaccharides, which are present as intermediates in the synthesis and catabolism of cell components, and (3) intracellular storage glucan. Colonial cells of Phaeocystis excrete (4) mucopolysaccharides, heteropolysaccharides that are the main constituent of the mucous colony matrix and (5) dissolved organic matter (DOM) rich in carbohydrates, which is mainly excreted by colonial cells. In this review the characteristics of these pools are discussed and quantitative data are summarized. During the exponential growth phase, the ratio of carbohydrate-carbon (C) to particulate organic carbon (POC) is approximately 0.1. When nutrients are limited, Phaeocystis blooms reach a stationary growth phase, during which excess energy is stored as carbohydrates. This so-called overflow metabolism increases the ratio of carbohydrate-C to POC to 0.4–0.6 during the stationary phase, leading to an increase in the C/N and C/P ratios of Phaeocystis organic matter. Overflow metabolism can be channeled towards both glucan and mucopolysaccharides. Summarizing the available data reveals that during the stationary phase of a bloom glucan contributes 0–51% to POC, whereas mucopolysaccharides contribute 5–60%. At the end of a bloom, lysis of Phaeocystis cells and deterioration of colonies leads to a massive release of DOM rich in glucan and mucopolysaccharides. Laboratory studies have revealed that this organic matter is potentially readily degradable by heterotrophic bacteria. However, observations in the field of accumulation of DOM and foam indicate that microbial degradation is hampered. The high C/N and C/P ratios of Phaeocystis organic matter may lead to nutrient limitation of microbial degradation, thereby prolonging degradation times. Over time polysaccharides tend to self-assemble into hydrogels. This may have a profound effect on carbon cycling, since hydrogels provide a vehicle to move DOM up the size spectrum to sizes subject to sedimentation. In addition, it changes the physical nature and microscale structure of the organic matter encountered by bacteria which may affect the degradation potential of the Phaeocystis organic matter.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Phaeocystis (Prymnesiophyceae) is a marine phytoplankton genus with a worldwide distribution. It is present from tropical to polar regions and can form blooms in areas with high nutrient concentrations, such as coastal or upwelling regions (Baumann et al. 1994; Lancelot et al. 1998; Schoemann et al. 2005). One of the characteristics of Phaeocystis species is the complex polymorphic life cycle. It consists of different stages of free-living cells 3–9 μm in diameter, alternating with colonial stages usually reaching several mm in diameter (Kornmann 1955; Rousseau et al. 1994; Peperzak et al. 2000), sometimes up to 3 cm (Chen et al. 2002). Although free-living Phaeocystis cells are ubiquitous in the world's oceans, it is the colonial form that has attracted most attention due to its massive blooms (Lancelot et al. 1987; Schoemann et al. 2005). At present six Phaeocystis species have been described (Zingone et al. 1999) of which only three are reported to form blooms; P. globosa in temperate regions (English Channel, coastal North Sea, China), P. pouchetii in temperate to polar waters of the Northern hemisphere, and P. antarctica in (sub)polar waters of the southern hemisphere (Schoemann et al. 2005). During blooms Phaeocystis may contribute over 90% to the total phytoplankton abundance and can be responsible for up to 65% of the local annual primary production (Joiris et al. 1982; Veldhuis et al. 1986b; Lancelot and Mathot 1987; Arrigo et al. 1999). The high productivity associated with blooms and its ubiquity make Phaeocystis an important contributor to the global carbon cycle (Smith et al. 1991; Arrigo et al. 1999; DiTullio et al. 2000; Schoemann et al. 2005). A significant part of the Phaeocystis carbon consists of carbohydrates (Lancelot and Mathot 1987; Rousseau et al. 1990; Fernández et al. 1992; Mathot et al. 2000). This vast carbohydrate injection following Phaeocystis blooms has a significant impact on the carbon cycling in the ecosystem and the microbial food web. Carbohydrates are omnipresent in the marine ecosystem, as they are an important constituent of marine DOM (Benner et al. 1992) and particles and therefore play a key role in the marine carbon cycle. Carbohydrates display a remarkable structural diversity as a consequence of the wide variety in aldoses and the different glycosidic bonds between them. These differences in structure and size influence the behavior of polysaccharides in aqueous solution, i.e., solubility and aggregate formation, as well as microbial degradation potential. To understand the impact of the carbohydrate injection after a Phaeocystis bloom on the carbon cycling in the ecosystem, it is important to consider the different types of carbohydrates that are produced. In the following sections we will first discuss the current state of knowledge with respect to the characteristics and quantities of different pools of carbohydrates produced during the various life cycle stages. Secondly, mechanisms of DOM release during and following a bloom will be discussed, and finally, the fate of carbohydrates in the microbial food web.

Phaeocystis carbohydrates and their characteristics

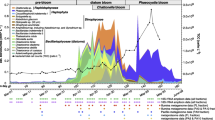

Carbohydrates in algae and plants are often classified based on methodological discrimination. The structural carbohydrates are not water-soluble, whereas the other types of carbohydrates are water-soluble and typically extracted by hot water. In Phaeocystis five different pools of carbohydrates can be distinguished. Like all algal and plant cells, both solitary and colonial cells produce (1) structural carbohydrates, polysaccharides that are mainly part of the cell wall, (2) mono- and oligosaccharides, which are present as intermediates in the synthesis and catabolism of cell components, and (3) intracellular storage glucan. Colonial cells of Phaeocystis excrete (4) mucopolysaccharides, heteropolysaccharides that are the main constituent of the mucous colony matrix and (5) dissolved organic matter (DOM) rich in carbohydrates, which is excreted mainly by colonial cells. A schematic on the procedure to extract the different types of particulate carbohydrates is depicted in Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of procedures to obtain different types of particulate carbohydrates from Phaeocystis cells concentrated on a filter. Total carbohydrates can directly be quantified colorimetrically. Water-soluble carbohydrates are typically extracted in hot water. They can be quantified colorimetrically. The 2,4,6-tripyridyl-s-triazine (TPTZ)-analysis (Myklestad et al. 1997) discriminates monosaccharides from larger carbohydrates. The aldose composition of water-soluble carbohydrates can be analyzed by gas chromatography (GC) or anion-exchange high-pressure liquid chromatography (AE-HPLC). Mucopolysaccharides can be separated from glucan and monosaccharides by ethanol precipitation (Alderkamp et al. 2006a), followed by colorimetric quantification of each fraction

Structural polysaccharides

In most algae and plants, structural carbohydrates are water-insoluble polysaccharides that are mainly present as cell wall constituents. Although Phaeocystis cells do not have a prominent cell wall, flagellate Phaeocystis cells are covered with body scales consisting of flat plates with a pattern of radiating ridges (Parke et al. 1971; Moestrup 1979; Hallegraeff 1983; Baumann et al. 1994). In two other haptophytes, Pleurochrysis scherfelii and Chrysochromulina chiton, the scales contain acidic, sulfated pectin-like polysaccharides, cellulose and glycopeptides (reviewed by Leadbeater 1994). Likely, Phaeocystis scales contain similar polysaccharides.

In addition to cellular structural carbohydrates, flagellate cells of Phaeocystis excrete filaments composed of α-chitin, an N-acetyl-d-glucosamine polymer, forming star-like structures. In electron microscopic studies, five-rayed filamentous stars were observed around flagellate cells of P. pouchetii, P. antarctica, P. globosa, and P. cordata, whereas nine-rayed stars were observed around P. scrobiculata (Parke et al. 1971; Moestrup 1979; Baumann et al. 1994; Chretiennot-Dinet et al. 1997; Zingone et al. 1999). The biological function of the chitin filaments remains a mystery up to now (Chretiennot-Dinet et al. 1997).

The only quantitative data available on the contribution of structural carbohydrates to Phaeocystis biomass are from a culture of Phaeocystis sp. in the stationary phase, where structural carbohydrates made up for 13% of the total organic carbon (TOC) (Biersmith and Benner 1998).

Mono- and oligosaccharides

Monosaccharides are the first products of photosynthesis and form the precursors for biosynthesis of all organic molecules, whereas oligosaccharides are intermediates in polysaccharide synthesis. During catabolism of storage glucan, monosaccharides are formed as intermediates (Granum and Myklestad 1999). In addition to intermediates in metabolic processes, monosaccharides serve a role in osmoregulation (Craigie 1974; Dickson and Kirst 1987a, b). The monosaccharide concentration in phytoplankton cells is quite stable; for example in diatoms monosaccharide concentration was hardly influenced by light (Vårum et al. 1986; Van Oijen et al. 2003). During the growth phase of a bloom of P. globosa in the Marsdiep, The Netherlands, the monosaccharides made up for 28–60% of water-extractable particulate carbohydrates (Alderkamp, unpublished data). This ratio was similar to an Antarctic community dominated by diatoms (Van Oijen et al. 2003).

Storage glucan

The principle food reserve in plants and algae is an intracellular food reserve in the form of a glucan, whereas some energy can be stored in lipids. Storage glucans may be α-1,4-glucans like starch or glycogen, or β-1,3-glucans like laminarin. The actual type of glucan is an important taxonomic characteristic. The class of Prymnesiophyceae contains β-1,3-glucan (Van den Hoek et al. 1993). β-1,3-glucans have an essentially linear β-d-1,3-glucan backbone with some branching at position 6 or 2 (Percival 1970; Craigie 1974; Myklestad 1978; Paulsen and Myklestad 1978). They can be classified as laminarin (also spelled laminaran), paramylon, or chrysolaminaran, distinguished mainly on the basis of chain length and presence of mannitol end groups. Laminarin has a degree of polymerization (DP-number of aldoses in the molecule) of approximately 20, contains mannitol-end groups, and is water-soluble. It is found in brown algae. Paramylon has a DP of more then 50, and does not contain mannitol end-groups or side chains. It is water-insoluble, and is found in euglenophytes (Manners et al. 1966). Chrysolaminaran (also called leucosin) has a DP of 16–38, contains no mannitol end-groups and is water-soluble. It is found in chrysophytes, haptophytes and diatoms (Myklestad and Haug 1972; Craigie 1974; Paulsen et al. 1978; Myklestad 1978, 1988). A different glucan structure has been found in the prymnesiophycean Emiliania huxleyi, that consists of a β-d-(1,6)-glucan backbone with branching at position 3 (Vårum et al. 1986). Phaeocystis cells contain chrysolaminaran as a storage glucan (Janse et al. 1996b). Chrysolaminaran is located in vacuoles, as was observed microscopically in Phaeocystis (Kornmann 1955; Parke et al. 1971; Chang 1984) and using immunolocalization of β-1,3-d-glucan in cell sections of the diatoms Phaeodactylum tricornutum, Cilindrotheca fusiformis and Thalassiosira pseudonana (Chiovitti et al. 2004). Due to its presence in ubiquitous bloom-forming phytoplankton chrysolaminaran it is considered to be one of the most abundant types of carbohydrate in the marine environment (Painter 1983).

Chrysolaminaran was characterized as principal storage glucan in a non-colony-forming strain of P. globosa that contained mainly non-flagellated cells (Janse et al. 1996b). In this strain, 95% of the water-extractable carbohydrates consisted of glucose and all glucose polymers were digested by the enzyme laminarinase (E.C. 3.2.1.6 from Trichoderma sp.). This enzyme preparation contained endo-β-1–3 glucanase activity and some chitinase, cellulase and α-amylase activity. Laminarin from the brown seaweed Laminaria digitata was digested to monosaccharides by this enzyme preparation. In colony-forming strains of P. globosa, however, no more than 40–70% of glucose polymers were digested (Van Rijssel et al. 2000; Alderkamp et al. 2006a). The reason for this partial digestion may be differences in the type of chrysolaminaran produced by single cells and colonial cells, e.g., with respect to polymer size or number of branches. Therefore, chrysolaminaran from colonial cells may not be fully degraded by the enzyme laminarinase. Alternatively, there may be a different type of glucan produced by colonial Phaeocystis cells.

In all plants photosynthetic rates exceed metabolic demands when irradiance is optimal. The excess energy thus harvested is stored mainly as glucan. This glucan can be used as a respiratory substrate to maintain growth when irradiance is suboptimal, for example during the night. Chrysolaminaran is produced in the light and its production is dependent on light intensity. Nocturnal respiration of chrysolaminaran provides energy to maintain cell metabolism and its carbon skeletons can be used for protein synthesis (Cuhel et al. 1984; Lancelot and Mathot 1985; Janse et al. 1996b; Granum et al. 1999; Granum and Myklestad 2001; Van Oijen et al. 2004b; Alderkamp et al. 2006a). Diel rhythms in storage carbohydrate concentrations have been well documented in laboratory cultures of diatoms (Hitchcock 1980; Vårum et al. 1986; Van Oijen et al. 2004b), field populations of pelagic marine phytoplankton dominated by diatoms (Barlow 1982; Hama and Handa 1992, Van Oijen et al. 2004b) and mesocosms dominated by P. pouchetii (Alderkamp et al. 2006a). Notably the diel variations in carbohydrate concentrations are a direct result of the variations in light intensity, but diel carbohydrate dynamics may also be the result of an intrinsic circadian clock (Post et al. 1985; Falkowski and Raven 1997). This was shown by Loogman (1982), who found that the diel dynamics in carbohydrate concentrations introduced by a diel light cycle, continued for several days after the light was switched to a continuous regime.

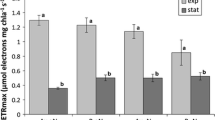

Under normal bloom conditions, Phaeocystis will experience varying light conditions during the day. On top of the diel light cycle, vertical mixing in the water column may mix colonies down to suboptimal light conditions, or even below the euphotic zone (Joint and Pomroy 1993; Arrigo et al. 1999; Wassmann et al. 2000). A capability to utilize stored energy is therefore likely to be important during the day as well as during the night. This may be relevant for Phaeocystis, since P. antarctica blooms occur in regions with deep wind-mixing (Arrigo et al. 1999), and P. globosa blooms often occur in turbid waters with high mixing rates, such as the coastal North Sea and estuaries. During sudden transitions from high to low light levels, carbohydrates can provide energy until cells are acclimatized to the new situation, as was shown in the diatom Thalassiosira weisflogii (Post et al. 1985). This was, however, not confirmed during a mesocosm study of P. pouchetii. Carbohydrate concentrations were unaffected by placing cells at low irradiances or in the dark during the day (Alderkamp et al. 2006a).

Upon nutrient limitation excess energy and carbon tend to accumulate as storage glucan, because the Calvin cycle and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle are uncoupled. Carbohydrate accumulation has been observed during the stationary growth phase of a single cell culture (Janse et al. 1996b), colonial cultures (Van Rijssel et al. 2000), and a bloom of P. globosa (Veldhuis et al. 1986a), and at the end of P. pouchetii blooms in mesocosms (Alderkamp et al. 2006a). This so-called overflow metabolism under nutrient limitation is common in phytoplankton (Myklestad 1974, 1988). It leads to an increased contribution of carbohydrates to the organic matter produced during bloom and an increased C/N ratio. Whereas the C/N ratio of exponentially growing free-living Phaeocystis cells and colonies is 4–7 (reviewed by Schoemann et al. 2005), C/N ratios as high as 20.5 were reported in nutrient limited mesocosms of P. pouchetii (Verity et al. 1988), 17.5 during blooms of P. pouchetii, and 30 during blooms of P. globosa at low ambient inorganic nitrogen concentrations (Baumann et al. 1994). Energy and carbon produced during overflow metabolism in Phaeocystis can be channeled towards both glucan and mucopolysaccharides. During the stationary phase of a P. pouchetii bloom in mesocosms the ratio glucan/mucopolysaccharides increased (Alderkamp et al. 2006a), whereas it decreased during the stationary phase of cultures of colonial P. globosa (Van Rijssel et al. 2000).

Blooms of P. antarctica occur in regions where trace metals, notably iron, are limiting phytoplankton growth (Martin et al. 1990; Coale et al. 2003, Schoemann et al. 2005). The effect of iron limitation on the overflow production by P. antarctica is largely unknown. Since iron limitation directly affects the photosynthetic process (Geider and La Roche 1994) the production of carbohydrates is likely to be hampered, thereby decreasing the overflow metabolism. Indeed, the diurnal production of water-extractable carbohydrates was reduced under iron limitation in the Antarctic diatom Chaetoceros brevis (Van Oijen et al. 2004a) and in an iron-limited phytoplankton community in the Southern Ocean, dominated by diatoms (Van Oijen et al. 2005). In accordance with these findings, only a minor increase in C/N ratio of P. antarctica was reported upon nutrient limitation in enclosures in the Ross Sea, where iron limitation is likely to occur (Smith et al. 1998). Therefore, it is unlikely that the overflow production under iron limitation will be as dramatic as under nitrogen or phosphorus limitation.

From the above it is clear that the concentration of storage glucan in phytoplankton is highly variable; it is dependent on the time of the day, light intensity and nutrient status of the cell. To evaluate the contribution of glucan to Phaeocystis carbon, quantitative data were compiled on the contribution of glucose to the aldose composition of particulate water-extractable carbohydrates (Fig. 1; Table 1a). Assuming that mucopolysaccharides consist of 10% glucose (Janse et al. 1999), the remaining glucose can be attributed to glucan. This leads to a highly variable contribution of glucan to the particulate water-extractable carbohydrate fraction of Phaeocystis colonies. During the exponential growth phase glucan contributes 14–85% and during the stationary phase 0–85%, both in culture and field samples. Alternatively, glucan and mucopolysaccharides were separated based on polymer size differences by ethanol precipitation (Fig. 1). During the growth phase of a P. pouchetii bloom in a mesocosm, glucan contributed 46–78% to particulate water-extractable carbohydrates, depending on the time of the day. This increased to 82% during the stationary phase of the bloom (Alderkamp et al. 2006a). To compute the contribution of glucan to colonial Phaeocystis POC, the carbohydrate-C/POC ratio of Alderkamp et al. (2006a) was used (Table 2). This leads to a contribution of glucan-C to POC of 2–11% during exponential growth, dependent on the time of the day. During the stationary phase the contribution ranges between 0% and 51%. The results are summarized in Table 3. In a non-colony-forming, non-flagellate strain of P. globosa, chrysolaminaran contributed 40% to TOC during the stationary phase (Janse et al. 1996b).

Mucopolysaccharides

The mucus matrix of Phaeocystis colonies consists predominantly of hetero-polysaccharides (Guillard and Hellebust 1971; Painter 1983; Lancelot and Mathot 1985; Eberlein et al. 1985; Van Boekel 1992). The mucopolysaccharides consist of at least nine different aldoses, are water-soluble, and polymers are larger than 1,000 kDa (Janse et al. 1999). Qualitative staining of the colony matrix indicated the absence of lipophilic compounds and chitin, but the presence of amino groups (Hamm et al. 1999). Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) analysis showed that N was not proteineous, but probably present in aminosugars (Solomon et al. 2003). The presence of the aminosugar sialic acid was confirmed by aminolabeling (Orellana et al. 2003). The presence of aminosugars may affect the C/N ratio of mucopolysaccharides, leading to a small difference between C/N ratios of single cells and colonial cells (Verity et al. 1988). Verity et al. (1991) concluded that the C/N ratio of the mucus constituents is lower than 9, whereas Biersmith and Benner (1998) measured a C/N ratio of 15.6 in the fraction containing mucopolysaccharides.

The aldose composition of P. globosa and P. pouchetii carbohydrates has been studied in bloom samples and in strains from different origins (Table 1a). The main non-glucose aldoses are arabinose, galactose, mannose and xylose. In addition, a minor contribution of rhamnose was detected in all samples, whereas fucose, ribose, O-methylated hexoses, O-methylated pentoses and glucuronic acid were detected in some samples only. The glucosamine detected by two groups may have been derived from copepod chitin contamination in the samples. The aldoses detected in Phaeocystis material are the same as those detected in other phytoplankton extracellular carbohydrates (Hoagland et al. 1993; Biersmith and Benner 1998), however, the ratio of constituents seems specific for Phaeocystis. There were no major differences in the presence or ratio of non-glucose aldoses between a bloom sample from Balsfjord, Norway, dominated by P. pouchetii and a sample from the North Sea dominated by P. globosa (Janse et al. 1999). No data are available for other species of Phaeocystis, including P. antarctica. In five different strains of P. globosa differences in the ratio of non-glucose constituents were small (Van Rijssel et al. 2000). Nutrient status of the cells does not seem to influence the ratio, as was shown in a batch culture of P. globosa (Van Rijssel et al. 2000) or in bloom samples taken at different stages of a bloom (Janse et al. 1996a). The change in colony shape and appearance at the end of Phaeocystis blooms (e.g., Verity et al. 1988; Rousseau et al. 1994) is therefore not reflected in the aldose composition of the mucopolysaccharides. This is different from the situation reported in diatoms, where upon nutrient limitation, the benthic diatom Cylindrotheca closterium excretes a separate extracellular polysaccharide with a different monosaccharide composition compared to optimal growth conditions (De Brouwer et al. 2002; Underwood et al. 2004).

Phaeocystis acts as a secretory cell; mucopolysaccharides are excreted in a way similar to animal cells and vascular plants in which the regulated export of cellular products takes place via exocytosis. While stored in secretory vesicles inside the cells, the mucopolysaccharides remain in condensed phase. Upon exocytosis, they undergo a characteristic phase transition accompanied by extensive swelling, resulting in the formation of hydrated gels (Chang 1984; Chin et al. 2004). The negatively charged mucopolysaccharides become entangled and form ionic links, such as calcium bridges (Van Boekel 1992). They then form a thin, yet strong, semipermeable colony matrix, with a pore size between 1 and 4.4 nm diameter, with plastic and to a limited extent also elastic properties (Kornmann 1955; Hamm et al. 1999). Electron microscope studies of a Phaeocystis sp. from Tasman Bay, New Zealand, show that the matrix has a multilayered gelatinous structure, with an average thickness of 5 μm (Chang 1984). Van Rijssel et al. (1997) calculated a thickness of 7 μm based on carbohydrate measurements and the assumption of a mucous layer with a fixed thickness for various colony sizes, whereas a thickness of 10 μm was determined based on confocal laser scanning imagery. As colonial cells of Phaeocystis have similar (Baumann et al. 1994), or even higher growth rates (Veldhuis et al. 2005) compared to single cells, the allocation of the material needed to build the colonial matrix obviously does not hamper cell metabolism.

In addition to a structural function in the mucous matrix, mucopolysaccharides were also suggested to serve as storage polysaccharides as nocturnal consumption of extracellular polysaccharides was reported in P. globosa (Lancelot and Mathot 1985; Veldhuis and Admiraal 1985). In both studies cells were separated from mucous matrix by filtration under pressure. Since this treatment may cause cells to break, thus releasing intracellular substances (see above), nocturnal consumption of intracellular chrysolaminaran may have been misreported as consumption of extracellular substances. Using the same method to separate extracellular material from cells, Matrai et al. (1995) observed no nocturnal utilization of extracellular polymers in an Antarctic strain of Phaeocystis. Also, when mucopolysaccharides and glucan were separated based on polymer size differences, no utilization of mucopolysaccharides was found when a culture of P. globosa was placed in the dark for prolonged times (Alderkamp et al. 2006a). Given the size and structure of mucopolysaccharides it seems unlikely that they serve as storage carbohydrate. Degradation and uptake of these complex polysaccharides would require multiple extracellular enzymes as well as transport systems to take up the different monosaccharides and oligomers. Moreover, since the gel matrix is such a definite structure stabilized by ionic bridges, it will be hard to disentangle polymers from the gel.

Contribution of mucopolysaccharides-C to POC

The contribution of mucus carbon to Phaeocystis organic carbon can be assessed in three different ways. In the first, cells are mechanically separated from the mucus matrix by filtration through GF/C filters. Fractionation by filtration yields contributions of 5–80% of mucus carbon to POC (reviewed by Riegman and Van Boekel 1996). As many have pointed out, however, Phaeocystis cells are fragile and may be disrupted by filtration under pressure (Veldhuis and Admiraal 1985; Van Rijssel et al. 1997; Mathot et al. 2000). By releasing their water soluble carbon the fraction of mucus-carbon may be overestimated. On the other hand, mucopolysaccharides may form gels on the filter (Chin et al. 1998) as a result of which their contribution may be underestimated. Therefore, all studies in which colonies were fractionated by filtration or centrifugation have to be interpreted with care.

When assuming that carbohydrates are the only significant source of carbon in the mucus matrix, the second method consists of determination of the contribution of mucopolysaccharides to the water-extractable carbohydrates. Mucopolysaccharides are estimated as the combined sum of all non-glucose aldoses and 10% of the glucose. Based on the aldose composition of water extractable carbohydrates (Fig. 1), the contribution of mucopolysaccharides to the water extractable particulate carbohydrates is 15–86% during the exponential growth phase, and 15–100% during the stationary phase (Table 1a and references therein). Alternatively, glucan and mucopolysaccharides were separated based on polymer size (Fig. 1; Alderkamp et al. 2006a). During the exponential growth phase, mucopolysaccharides contributed 38% to the water extractable carbohydrates, decreasing to 9% during the stationary phase. Based on the carbohydrate-C to carbon ratios of Alderkamp et al. (2006a; Table 2) the contribution of mucopolysaccharides to POC is estimated as 2–11% during exponential growth and 5–60% during the stationary phase.

The third method to estimate the carbon of colony matrices is based on conventional conversion factors for determining the carbon content of the average cell biovolume of Phaeocystis cells and an additional carbon content of the mucus matrix. In P. antarctica, Mathot et al. (2000) found on average 14% of POC devoted to matrix formation, increasing to a maximum of 33%. In P. globosa Rousseau et al. (1990) using a colony-volume-based model, calculated up to 90% of POC devoted to matrix formation in large colonies. Van Rijssel et al. (2000), assuming a hollow colony surrounded by a thin mucus layer and using a colony-surface-based model, calculated a contribution up to 35%. Comparisons of estimates obtained by these authors, however, show similar POC contributions for colony sizes predominantly observed in the field (reviewed by Schoemann et al. 2005). The estimates for the contribution of mucous matrix-C to POC are summarized in Table 4.

Extra-colonial DOM

Extra-colonial DOM rich in carbohydrates was reported in cultures of Phaeocystis (Table 5 and references therein). Carbohydrates similar in aldose composition to that of mucopolysaccharides form a major contribution to this DOM (Table 1b). There seem to be two different pools of DOM; (1) a high-molecular-weight (HMW)-DOM pool with a high C/N ratio of over 12 and a carbohydrate content of over 67% and (2) a low-molecular-weight (LMW)-DOM pool with a low C/N ratio of 6.3. Since all studies used filtration techniques applying pressure, it is most likely that the DOM also contained mucopolysaccharides. The overall C/N ratio of the DOM is low, around 7 (Biddanda and Benner 1997; Solomon et al. 2003). Similar to mucopolysaccharides, extra-colonial polymers self assemble in hydrated polymer gels on a time scale of approximately two days (Solomon et al. 2003).

High DOM concentrations have been reported in natural assemblages dominated by Phaeocystis (Eberlein et al. 1985), and high DOM excretion rates in cultures (Guillard and Hellebust 1971). Upon careful filtration, however, true extra-colonial DOM excretion was only 14% of primary production in the late exponential phase of a P. globosa culture (Veldhuis and Admiraal 1985; Veldhuis et al. 1986a; Biersmith and Benner 1998), and 2–14% of primary production in natural assemblages dominated by P. globosa (Laanbroek et al. 1985; Veldhuis et al. 1986a; Lancelot and Mathot 1987). Similar values were observed for P. pouchetii (1–19%; Verity et al. 1991), and during a bloom of P. antarctica (11%; Carlson et al. 1998).

Mechanisms of DOM release during a Phaeocystis bloom

In general 10–25% of phytoplankton primary production is released as DOC (Sharp 1977; Larsson and Hagström 1979; Lignell 1990; Teira et al. 2003; Marañón et al. 2004). The three main mechanisms of DOM production are: (1) release after cell lysis, e.g., as a result of viral infection, zooplankton sloppy feeding and egestion, (2) bacterial cleavage of exopolysaccharides (Smith et al. 1995), or (3) direct release as a physiological process of intact cells (reviewed by Nagata 2000). Two physiological mechanisms of DOM production have been advocated: a passive diffusion of small metabolites through the cell membrane (Bjørnsen 1988) and an overflow mechanism whereby excess photosynthetic products are actively released when the C fixation rate exceeds the rate of macromolecular production (Fogg 1983).

During the exponential growth phase of a Phaeocystis bloom DOM release as a result of non-physiological processes will be low. In a P. globosa bloom rates of cell lysis were low in the growth phase (Van Boekel et al. 1992; Brussaard et al. 1995, 1996, 2005a), therefore DOM release as a result of cell lysis will be insignificant. Since Phaeocystis colonies largely escape grazing control (Breteler and Koski 2003; Nejstgaard et al. 2007), sloppy feeding will not be a cause of significant DOM release either. In a diatom bloom it was shown that bacteria colonized healthy, actively growing Chaetoceros and Thalassiosira cells with high ectoenzyme activity. When the hydrolysis rate of phytoplankton surface material by bacteria exceeds the uptake rate, DOM will be released into the environment (Smith et al. 1995). Although the growth phase of P. globosa blooms are typically accompanied by an increase in bacterial numbers, bacterial production, and enzyme activity (Billen and Fontigny 1987; Van Boekel et al. 1992; Putt et al. 1994; Becquevort et al. 1998; Arrieta and Herndl 2002; Brussaard et al. 1996, 2005b), young healthy colonies are generally free of bacteria (Thingstad and Billen 1994; Lancelot and Rousseau 1994). Therefore, it is unlikely that hydrolysis of the mucous matrix by bacteria will lead to significant DOM production during the growth phase of the bloom. The only significant mechanisms for DOM production is probably direct release of DOM from healthy cells. During all growth stages DOM excretion from healthy cells was observed in cultures of Phaeocystis sp. (Biddanda and Benner 1997). Since DOM excretion rates are low (see above) on the whole DOM release during the growth phase of the bloom will be low.

During the stationary phase of a bloom, however, DOM release increases. During the stationary phase colonies become disrupted, and flagellate cells develop within the colonies (Peperzak et al. 2000). Due to the overflow production of mucopolysaccharides and glucan, the ratio of carbohydrates-C to POC increases. During this phase of a bloom DOM production through non-physiological processes will be high. Cell lysis rates of up to 33% day−1 were observed at the peak of P. globosa blooms (Van Boekel et al. 1992; Brussaard et al. 1995, 1996, 2005a). In this way the carbohydrate rich cell content is released as DOM. When the flagellate cells that develop inside colonies detach from the colony matrix, they are readily grazed upon by microzooplankton (Weisse and Scheffel-Möser 1990; Tang et al. 2001). This leads to DOM release by egestion of the microzooplankton. During the stationary phase of a bloom, bacterial communities attach to Phaeocystis colonies and to ghost colonies. Bacteria with high glucosidase activity are present in both free-living and particle-attached communities (Billen and Fontigny 1987; Becquevort et al. 1998). If hydrolysis rates of mucopolysaccharides from the colony matrix exceeds uptake of the sugars, the sugars and oligomers derived from mucopolysaccharides may be released as DOM.

The excess release of DOM under nutrient limitation has not been observed in Phaeocystis. In Phaeocystis sp. cultures DOC production was coupled to POC production at different growth stages (Biddanda and Benner 1997). Also in enclosures of P. antarctica, ratios of recently produced DOC increased only slightly after nutrient depletion (Smith et al. 1998; Carlson et al. 1998). This indicates that nutrient limitation does not lead to increased excretion of DOM resulting from an overflow mechanism.

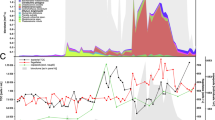

Formation of hydrogels by Phaeocystis carbohydrates

Polysaccharides in aqueous environments may spontaneously assemble into hydrogels. These polymer gels can then penetrate neighboring gels, and anneal them together, increasing the size spectrum. Recent discoveries have highlighted the importance of polymer gels for biogeochemical cycling of organic carbon (see the review by Verdugo et al. 2004). As was discussed above, mucopolysaccharides spontaneously form polyanionic gels in aqueous solution. In addition to gel formation by mucopolysaccharides, β-1,3-glucans are also known to form non-ionic gels in aqueous solutions (Renn 1997; Kim et al. 2000). In general, gelling properties of β-glucans are dependent on the concentration of the molecules, their size, primary and secondary structure and temperature (Bohm and Kulicke 1999; Lazaridou et al. 2003). Therefore, gel-forming properties of laminarin in the marine environment are hard to predict. Preliminary results from our laboratory show that dissolving laminarin in seawater leads to an increase in viscosity, but to our knowledge no further investigations have been conducted to this end. Seuront et al. (2007) showed that Phaeocystis derived polymeric matter could increase seawater viscosity up to two orders of magnitude. Because of the high aggregation potential of both glucan and mucopolysaccharides, the carbohydrates released during senescence of the Phaeocystis bloom will likely contribute to the increase in seawater viscosity (Fig. 2), thereby changing the physical nature and microscale structure of the organic matter encountered by bacteria.

Conceptual representation of the formation of marine gels from different pools of Phaeocystis organic matter (after Verdugo et al. 2004). (abbreviations: LMW-DOM: low-molecular-weight DOM, HMW-DOM: high-molecular-weight DOM, POM: particulate organic matter, TEP: transparent exopolymeric particles)

Gels provide an abiotic vehicle to move organic molecules up the size spectrum to sizes capable of sedimentation, and may also constitute an intermediate in the formation of the foam often observed after Phaeocystis blooms (Fig. 2). Large gel particles, also known as transparent exopolymeric particles (TEP) can contribute significantly to sedimentation processes. This may be by direct sedimentation (Wassmann et al. 1990; Riebesell et al. 1995; Hong et al. 1997), or by acting as glue, adhering together organic matter present during a bloom and thus enhancing their contribution to a vertical flux (Passow and Wassmann 1994). Mari et al. (2005) showed that the properties of TEP produced under N or P limitation are different, as a result of which the export versus retention balance of the organic matter may be affected. It is tempting to speculate that the different N/P ratios may determine whether overflow metabolism is directed towards either glucan or mucopolysaccharide production. This would resemble the situation described for the diatom Cylindrotheca fusiformis, where P depletion leads to an increase in the ratio of heteropolysaccharides to glucan, compared to N-limitation (Magaletti et al. 2004). In this way the glucan/mucopolysaccharides ratio may influence properties of the hydrogels and TEP that is formed, and thereby the degradation potential of Phaeocystis organic matter.

Microbial degradation

Generally, most of the biomass produced in Phaeocystis blooms is remineralized in the water column (Wassmann 1994, Rousseau et al. 2000) by heterotrophic bacteria. Occasionally, however, accumulation of DOM and foam have been reported (e.g. Eberlein et al. 1985; Lancelot et al. 1987; Seuront et al., 2007). This seems to indicate that bacterial degradation of organic matter produced by in Phaeocystis blooms varies between blooms, and sometimes is hampered. There may be various reasons for slow degradation and they may be different in different stages of a bloom.

Microbial degradation of Phaeocystis carbohydrates

During the growth phase of a bloom of P. antarctica all DOM produced was found to be rapidly degraded by bacteria (Smith et al. 1998). With time, however, the composition and contribution of organic matter that can be utilized by bacteria will change from readily degradable freshly excreted DOM during the growth phase, to the DOM dominated by mucopolysaccharides and glucan during the senescent stage. In laboratory experiments it was shown that carbohydrates derived from P. globosa and P. pouchetii colonies were readily degraded by bacterial communities under both oxic and anoxic conditions (Osinga et al. 1997; Janse et al. 1999). The degradation rate of glucan was higher than that of mucopolysaccharides (Osinga et al. 1997), but during degradation of the mucopolysaccharides the sugar composition of the mucopolysaccharides remained unchanged. Therefore, there is no indication of refractory parts within the mucopolysaccharide fraction (Janse et al. 1999).

Identification of bacteria involved in mucopolysaccharide degradation in cultures and a mesocosm revealed the presence of bacteria from different phylogenetic groups, such as α- and γ-Proteobacteria, Cytophaga-Flavobacter (CF) cluster of the Bacteroidetes and the Planktomycetes and Verrucomicrobiales clade (Janse et al. 2000; Brussaard et al. 2005b; Alderkamp et al 2006b). During a P. globosa bloom in a mesocosm the bacterial community showed distinct changes with time (Brussaard et al. 2005b). The nature of the phytoplankton growth controlling substrate (i.e., N or P) did not influence the microbial community. In addition, since the species composition of the bacterial community remained unchanged during mucopolysaccharide degradation, degradation of mucopolysaccharides in itself does not require a succession of species (Janse et al. 2000). Therefore, the changes in the microbial community were likely induced by the growth stage of the P. globosa bloom and enhanced cell lysis and concomitant release of DOM during the senescent stage (Brussaard et al. 2005b). Degradation of polymers requires specialized extracellular enzyme systems to hydrolyze polymers prior to uptake by bacteria. These enzymes can be attached to the bacterial cell (ectoenzymes), or free extracellular enzymes (Chróst 1991). Arrieta and Herndl (2002) revealed a succession of different types of bacterial β-glucosidases during a P. globosa bloom, which was related to a change in the bacterial community. Therefore, the copious amounts of glucan and mucopolysaccharides produced during a Phaeocystis bloom may shape the composition of bacterial communities specialized in degradation of complex carbohydrates. Bacteria appearing during the senescent stage of the P. globosa bloom in the mesocosm mainly belonged to the α-Proteobacteria and CF cluster of the Bacteroidetes (Brussaard et al. 2005b). In the coastal North Sea, bacteria from CF clusters of the Bacteroidetes were dominant during and following a bloom of P. globosa (A. C. Alderkamp et al. 2006b). Members of the CF cluster are chemo-organotrophic, and known for their capacity to degrade complex carbohydrates such as pectin, cellulose and chitin (Reichenbach and Dworkin 1991; Cottrell and Kirchman 2000; Kirchman 2002). Therefore, it may be that certain taxa of this cluster have adapted specifically to degradation of complex mucopolysaccharides produced by Phaeocystis.

Mineral nutrient limitation of microbial degradation has been put forward as an explanation for accumulation of carbon-rich DOM after a Phaeocystis bloom (Thingstad and Billen 1994). The increase in carbohydrate/POC due to overflow metabolism will give rise to a substrate with a C/P and C/N ratio that is unfavorable to bacteria. Since the C/P ratio of bacteria may be considerably lower than that of phytoplankton (Vadstein et al. 1988), especially phosphate limitation may hamper microbial degradation (Thingstad et al. 1997). In addition, since P. antarctica was found to remove more CO2 per mole of phosphate than do diatoms (Arrigo et al. 1999), phosphate limitation during bacterial degradation of Phaeocystis material may be more severe than during degradation of diatom material. Indeed, while bacterial growth was carbon limited during the growth phase of a bloom of P. globosa, bacterial growth was colimited by carbon and phosphate during the massive release of the glucan and mucopolysaccharides at the end of the bloom (Kuipers and Van Noort, in preperation). This may impede degradation of carbohydrates that are otherwise easily degradable, and prolong the degradation times.

Microbial degradation of hydrogels

Marine gels likely have an effect on microbial degradation of organic matter, yet few studies have examined this effect directly. Based on the current knowledge, gel formation may either enhance or slow down degradation of organic matter. In general HMW-DOC and gels have a higher rate of biodegradation and turnover than LMW-DOC (Amon and Benner 1996). Gels may serve as nutrient and/or attachment surfaces and offer hot-spots of high substrate concentrations for bacteria. They form enclosed microenvironments of substrate for bacteria to colonize, release their extracellular enzymes and efficiently take up the degradation products at high local concentrations (Azam 1998; Azam and Long 2001). Indeed, following a P. globosa bloom bacteria attached to particles were more active than the free-living community (Becquevort et al. 1998). On the other hand, assembly of free polymers into gels may complicate degradation. Enzymatic degradation of carbohydrates that form insoluble gels was approximately 50 times slower than degradation of polymers composed of the same monomer linkages, but not forming gels (Alderkamp et al. 2007). If this difference is exemplary of the difference in degradation potential of ‘free’ polymers and polymers embedded in a gel, turnover times may slow down from days to years.

Microbial degradation dissolves the hydrogels when hydrolysis rates exceed the carbon demand of the bacteria, thereby releasing LMW products from the hydrogels (Smith et al. 1992; Fig. 3). Moreover, the kinetic properties of bacterial enzyme systems may result in the release of oligomers at a higher rate than the release of monomers that can be directly incorporated by the bacteria, resulting in release of LMW and medium molecular-weight (MMW) products (Alderkamp et al. 2007). In addition, polymer photocleavage by ultraviolet radiation can shorten polymer chains making tangled networks unstable (Edwards 1986) and can readily disperse marine polymer gel matrices (Orellana and Verdugo 2003). These three processes produce a random fragmentation, yielding LMW products that may be readily incorporated and metabolized by bacteria (Mopper et al. 1991; Moran and Zepp 1997; Mopper and Kieber 2001), adding to a rapid degradation of the organic matter in hydrogels. On the other hand, polymers may be released that are too large to be transported by bacterial permeases, yet too small to assemble into stable networks that bacteria can colonize and efficiently degrade with their extracellular enzymes. These polymers, indicated as DOM (MMW-DOM) in Fig. 3, may contribute to the formation of refractory DOM.

Conceptual representation of biotic and abiotic processes altering the size and recalcitrance of organic matter. (Abbreviations as in Fig. 1, MMW-DOM: medium-molecular-weight DOM)

Bacterial activity may also increase aggregation of gels (Fig. 3). Studies on bacterial exopolymer production suggest that a significant portion of assimilated carbon is incorporated into exopolymer capsular envelopes (Stoderegger and Herndl 1998). These capsular exopolymers increase aggregation probabilities of phytoplankton and other particles and act as stabilizers of already existing aggregates (Allison and Sutherland 1987; Decho 1990; Heissenberger and Herndl 1994). In addition, bacterial exopolymers are resistant against bacterial enzymatic degradation, since a considerable fraction of bacterial extracellular enzymes are embedded in the exopolymer capsule. Therefore, release of bacterial derived exopolymers decreases the degradation potential of hydrogels. Finally, selective degradation of readily degradable compounds may alter the composition of the gels, and decrease the degradation potential of the remaining gel (Sannigrahi et al. 2005). At present it is not known to what extent the mechanisms discussed above influence microbial degradation of hydrogels. Therefore, microbial degradation of Phaeocystis derived DOM may either be enhanced or hampered by formation of hydrogels.

Conclusions

Phaeocystis produces at least five different pools of carbohydrates, each with their own characteristics. Since the overflow metabolism during the stationary phase of a bloom can be channeled towards glucan and mucopolysaccharides, these two pools are quantitatively the most important when the impact on the ecosystem is considered. The contribution of the pools is strongly dependent on environmental conditions. High light conditions and nutrient limitation lead to excess carbohydrate production, but thus far the effect of either N or P limitation on the ratio of glucan to mucopolysaccharide production is unclear, as is the effect of Fe limitation on carbohydrate production in P. antarctica.

Phaeocystis-derived organic matter appears to be readily degradable, however, the high C/N and C/P ratios may give rise to mineral nutrient limitation of bacteria and therefore hamper degradation. Subsequent assembly into gels could have a dramatic effect on bacterial degradation of Phaeocystis derived organic matter, however, the nature of this effect is unclear. Gels may provide a convenient microhabitat to colonize and degrade with extracellular enzymes, thereby enhancing degradation rates of organic matter. Conversely, degradation of polymers embedded in gels may be slowed down by sterical hindrance. Furthermore, bacterial activity may reduce the degradation potential of gels by selective degradation of labile organic matter in the gels, and by production of carbon into bacterial capsular material.

References

Alderkamp AC, Nejstgaard JC, Verity PG, Zirbel MJ, Sazhin AF, Van Rijssel M (2006a) Dynamics in carbohydrate composition of Phaeocystis pouchetii colonies during spring blooms in mesocosm. J Sea Res 55:169–181

Alderkamp AC, Sintes E, Herndl GJ (2006b) Abundance and activity of major groups of prokaryotic plankton in the coastal North Sea during the wax and wane of a phytoplankton spring bloom. Aquat Microb Ecol 45:237–246

Alderkamp AC, Van Rijssel M, Bolhuis H (2007) Characterization of marine bacteria and the activity of their enzyme systems involved in degradation of the algal storage glucan laminarin. FEMS Microb Ecol 59:108–117

Allison DG, Sutherland IW (1987) The role of exopolysaccharides in adhesion of fresh-water bacteria. J Gen Microbiol 133:1319–1327

Aluwihare LI, Repeta DJ (1999) A comparison of the chemical characteristics of oceanic DOM and extracellular DOM produced by marine algae. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 186:105–117

Amon RMW, Benner R (1996) Bacterial utilization of different size classes of dissolved organic matter. Limnol Oceanogr 41:41–51

Arrieta JM, Herndl GJ (2002) Changes in bacterial beta-glucosidase diversity during a coastal phytoplanktonbloom. Limnol Oceanogr 47:594–599

Arrigo KR, Robinson DH, Worthen DL, Dunbar RB, DiTullio GR, VanWoert M, Lizotte MP (1999) Phytoplankton community structure and the drawdown of nutrients and CO2 in the Southern Ocean. Science 283:365–367

Azam F (1998) Microbial control of oceanic carbon flux: the plot thickens. Science 280:694–696

Azam F, Long RA (2001) Oceanography – sea snow microcosms. Nature 414:495–498

Barlow RG (1982) Phytoplankton ecology in the Southern Benguela Current .3. Dynamics of a bloom. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 63:239–248

Baumann MEM, Lancelot C, Brandidni FP, Sakshaugh E, John DM (1994) The taxonomic identity of the cosmopolitan prymnesiophyte Phaeocystis: a morphological and ecophysiological approach. J Mar Syst 5:5–22

Becquevort S, Rousseau V, Lancelot C (1998) Major and comparable roles for free-living and attached bacteria in the degradation of Phaeocystis-derived organic matter in Belgian coastal waters of the North Sea. Aquat Microb Ecol 14:39–48

Benner R, Pakulski JD, McCarty M, Hedges JI, Hatcher PG (1992) Bulk chemical characteristics of dissolved organic matter in the ocean. Science 255:1561–1564

Biddanda B, Benner R (1997) Carbon, nitrogen, and carbohydrate fluxes during the production of particulate and dissolved organic matter by marine phytoplankton. Limnol Oceanogr 42:506–518

Biersmith A, Benner R (1998) Carbohydrates in phytoplankton and freshly produced dissolved organic matter. Mar Chem 63:131–144

Billen G, Fontigny A (1987) Dynamics of a Phaeocystis-dominated spring bloom in Belgian coastal waters. II Bacterioplankton dynamics. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 37:249–257

Bjørnsen PK (1988) Phytoplankton exudation of organic-matter – why do healthy cells do it? Limnol Oceanogr 33:151–154

Bohm N, Kulicke WM (1999) Rheological studies of barley (1->3)(1->4)-beta-glucan in concentrated solution: mechanistic and kinetic investigation of the gel formation. Carbohydr Res 315:302–311

Breteler WCMK, Koski M (2003) Development and grazing of Temora longicornis (Copepoda, Calanoida) nauplii during nutrient limited Phaeocystis globosa blooms in mesocosms. Hydrobiologia 491:185–192

Brussaard CPD, Riegman R, Noordeloos AAM, Cadée GC, Witte H, Kop AJ, Nieuwland G, Van Duyl FC, Bak RPM (1995) Effects of grazing, sedimentation and phytoplankton cell lysis on the structure of a coastal pelagic food web. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 123:259–271

Brussaard CPD, Gast GJ, Van Duyl FC, Riegman R (1996) Impact of phytoplankton bloom magnitude on a pelagic microbial food web. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 144:211–221

Brussaard CPD, Kuipers B, Veldhuis MJW (2005a) A mesocosm study of Phaeocystis globosa population dynamics – 1. Regulatory role of viruses in bloom. Harmful Algae 4:859–874

Brussaard CPD, Mari X, Van Bleijswijk JDL, Veldhuis MJW (2005b) A mesocosm study of Phaeocystis globosa (Prymnesiophyceae) population dynamics – II. Significance for the microbial community. Harmful Algae 4:875–893

Carlson CA, Ducklow HW, Hansell DA, Smith WO (1998) Organic carbon partitioning during spring phytoplankton blooms in the Ross Sea polynya and the Sargasso Sea. Limnol Oceanogr 43:375–386

Chang FH (1984) The ultrastructure of Phaeocystis pouchetii (Prymnesiophyceae) vegetative colonies with special reference to the production of new mucilaginous envelope. N Z J Mar Fresh Res 18:303–308

Chen YQ, Wang N, Zhang P, Zhou H, Qu LH (2002) Molecular evidence identifies bloom-forming Phaeocystis (Prymnesiophyta) from coastal waters of southeast China as Phaeocystis globosa. Biochem Syst Ecol 30:15–22

Chin WC, Orellana MV, Verdugo P (1998) Spontaneous assembly of marine dissolved organic matter into polymer gels. Nature 391:568–572

Chin WC, Orellana MV, Quesada I, Verdugo P (2004) Secretion in unicellular marine phytoplankton: demonstration of regulated exocytosis in Phaeocystis globosa. Plant Cell Physiol 45:535–542

Chiovitti A, Molino P, Crawford SA, Teng RW, Spurck T, Wetherbee R (2004) The glucans extracted with warm water from diatoms are mainly derived from intracellular chrysolaminaran and not extracellular polysaccharides. Eur J Phycol 39:117–128

Chretiennot-Dinet MJ, Giraud-Guille MM, Vaulot D, Putaux JL, Saito Y, Chanzy H (1997) The chitinous nature of filaments ejected by Phaeocystis (Prymnesiophyceae). J Phycol 33:666–672

Chróst RJ (1991) Environmental control of the synthesis and activity of aquatic microbial ectoenzymes. In: Chróst RJ (ed) Microbial enzymes in aquatic environments. Springer Verlag, New York, pp 29–59

Coale KH, Wang XJ, Tanner SJ, Johnson KS (2003) Phytoplankton growth and biological response to iron and zinc addition in the Ross Sea and Antarctic Circumpolar Current along 170 degrees W. Deep-Sea Res II 50:635–653

Cottrell MT, Kirchman DL (2000) Natural assemblages of marine proteobacteria and members of the Cytophaga-Flavobacter cluster consuming low- and high-molecular-weight dissolved organic matter. Appl Environ Microbiol 66:1692–1697

Craigie JS (1974) Storage products. In: Stewart WDP (ed) Algal physiology and biochemistry. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford, pp 206–235

Cuhel RL, Ortner PB, Lean DRS (1984) Night synthesis of protein by algae. Limnol Oceanogr 29:731–744

De Brouwer JFC, Wolfstein K, Stal LJ (2002) Physical characterization and diel dynamics of different fractions of extracellular polysaccharides in an axenic culture of a benthic diatom. Eur J Phycol 37:37–44

Decho AW (1990) Microbial exopolymer secretions in ocean environments – their role(s) in food webs and marine processes. Oceanogr Mar Biol 28:73–153

Dickson DMJ, Kirst GO (1987a) Osmotic adjustment in marine eukaryotic algae – the role of inorganic-ions, quaternary ammonium, tertiary sulfonium and carbohydrate solutes.1. Diatoms and a rhodophyte. New Phytol 106:645–655

Dickson DMJ, Kirst GO (1987b) Osmotic adjustment in marine eukaryotic algae – the role of inorganic-ions, quaternary ammonium, tertiary sulfonium and carbohydrate solutes. 2. Prasinophytes and haptophytes. New Phytol 106:657–666

DiTullio GR, Grebmeier JM, Arrigo KR, Lizotte MP, Robinson DH, Leventer A, Barry JB, VanWoert ML, Dunbar RB (2000) Rapid and early export of Phaeocystis antarctica blooms in the Ross Sea, Antarctica. Nature 404:595–598

Eberlein K, Leal MT, Hammer KD, Hickel W (1985) Dissolved organic substances during a Phaeocystis pouchetii bloom in the German Bight (North Sea). Mar Biol 89:311–316

Edwards SF (1986) The theory of macromolecular networks. Biorheology 23:589–603

Falkowski PG, Raven JA (1997) Aquatic photosynthesis. Blackwell Science, Malden, MA

Fernández E, Serret P, Demadariaga I, Harbour DS, Davies AG (1992) Photosynthetic carbon metabolism and biochemical composition of spring phytoplankton assemblages enclosed in microcosms: the diatom Phaeocystis sp. succession. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 90:89–102

Fogg GE (1983) The ecological significance of extracellular products of phytoplankton photosynthesis. Bot Mar 26:3–14

Geider RJ, La Roche J (1994) The role of iron in phytoplankton photosynthesis and the potential for iron-limitation of primary productivity in the sea. Photosynth Res 39:275–301

Granum E, Myklestad SM (1999) Effects of NH4+ assimilation on dark carbon fixation and beta-1,3-glucan metabolism in the marine diatom Skeletonema costatum (Bacillariophyceae). J Phycol 35:1191–1199

Granum E, Myklestad SM (2001) Mobilization of beta-1,3-glucan and biosynthesis of amino acids induced by NH4+ addition to N-limited cells of the marine diatom Skeletonema costatum (Bacillariophyceae). J Phycol 37:772–782

Guillard RRL, Hellebust JA (1971) Growth and production of extracellular substances by two strain of Phaeocystis pouchetii. J Phycol 7:330–338

Hallegraeff GM (1983) Scale-bearing and loricate nanoplankton from the East Australian Current. Bot Mar 16:515

Hama J, Handa N (1992) Diel variation of water-extractable carbohydrate composition of natural phytoplankton populations in Kinu-ura Bay. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 162:159–176

Hamm CE, Simson DA, Merkel R, Smetacek V (1999) Colonies of Phaeocystis globosa are protected by a thin but tough skin. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 187:101–111

Heissenberger A, Herndl GJ (1994) Formation of high molecular weight material by free-living marine bacteria. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 111:129–135

Hitchcock GL (1980) Diel variation in chlorophyll a, carbohydrate and protein content of the marine diatom Skeletonema costatum. Mar Biol 57:271–278

Hoagland KD, Rosowski JR, Gretz MR, Roemer SC (1993) Diatom extracellular polymeric substances: function, fine structure, chemistry, and physiology. J Phycol 29:537–566

Hong Y, Smith WO, White AM (1997) Studies on transparent exopolymer particles (TEP) produced in the Ross Sea (Antarctica) and by Phaeocystis antarctica (Prymnesiophyceae). J Phycol 33:368–376

Janse I, Van Rijssel M, Gottschal JC, Lancelot C, Gieskes WWC (1996a) Carbohydrates in the North Sea during spring blooms of Phaeocystis: a specific fingerprint. Aquat Microb Ecol 10:97–103

Janse I, Van Rijssel M, Van Hall PJ, Gerwig GJ, Gottschal JC, Prins RA (1996b) The storage glucan of Phaeocystis globosa (Prymnesiophyceae) cells. J Phycol 32:382–387

Janse I, Van Rijssel M, Ottema A, Gottschal JC (1999) Microbial breakdown of Phaeocystis mucopolysaccharides. Limnol Oceanogr 44:1447–1457

Janse I, Zwart G, Maarel MJEC, Gottschal JC (2000) Composition of the bacterial community degrading Phaeocystis mucopolysaccharides in enrichment cultures. Aquat Microb Ecol 22:119–133

Joint I, Pomroy A (1993) Phytoplankton biomass and production in the southern North-Sea. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 99:169–182

Joiris C, Billen G, Lancelot C, Daro MH, Mommaerts JP, Bertels A, Bossicart M, Nijs J, Hecq JH (1982) A budget of carbon cycling in the Belgian coastal zone: relative roles of zooplankton, bacterioplankton and benthos in the utilization of primary production. Neth J Sea Res 16:260–275

Kim YT, Kim EH, Cheong C, Williams DL, Kim CW, Lim ST (2000) Structural characterization of beta-D-(1 fwdarw 3, 1 fwdarw 6)-linked glucans using NMR spectroscopy. Carbohydr Res 328:331–341

Kirchman DL (2002) The ecology of Cytophaga-Flavobacteria inaquatic environments. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 39:91–100

Kornmann P (1955) Beobachtungen an Phaeocystis-Kulturen. Helgol Wiss Meeresunters 5:218–233

Laanbroek HL, Verplanke JC, De Visscher PRM, De Vuyst R (1985) Distribution of phyto- and bacterioplankton growth and biomass parameters, dissolved inorganic nutrients and free amino acids during a spring bloom in the Oosterschelde basin, The Netherlands. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 25:1–11

Lancelot C, Mathot S (1985) Biochemical fractionation of primary production by phytoplankton in Belgian coastal waters during short- and long-term incubations with 14C-bicarbonate. II. Phaeocystis poucheti colonial population. Mar Biol 86:227–232

Lancelot C, Mathot S (1987) Dynamics of a Phaeocystis-dominated spring bloom in Belgian coastal waters. I Phytoplanktonic activities and related parameters. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 37:239–248

Lancelot C, Rousseau V (1994) Ecology of Phaeocystis: the key role of colony forms. In: Green JC, Leadbeater BSC (eds) The haptophyte algae. Clarendon Press, Oxford, pp 229–245

Lancelot C, Billen G, Sournia A, Weisse T, Colijn F, Veldhuis MJW, Davies A, Wassmann P (1987) Phaeocystis blooms and nutrient enrichment in the continental coastal zones of the North Sea. Ambio 16:38–46

Lancelot C, Keller MD, Rousseau V, Smith WO, Mathot S (1998) Autoecology of the marine haptophyte Phaeocystis sp. In: Anderson DM, Cembella AD, Hallegraeff GM (eds) Physiological ecology of harmful algal blooms. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, pp 209–224

Larsson U, Hagström A (1979) Phytoplankton exudate release as an energy-source for the growth of pelagic bacteria. Mar Biol 52:199–206

Lazaridou A, Biliaderis CG, Izydorczyk MS (2003) Molecular size effects on rheological properties of oat beta-glucans in solution and gels. Food Hydrocolloids 17:693–712

Leadbeater BSC (1994) Cell coverings. In: Green JC, Leadbeater BSC (eds) The haptophyte algae. Clarendon Press, Oxford, pp 23–46

Lignell R (1990) Excretion of organic-carbon by phytoplankton – its relation to algal biomass, primary productivity and bacterial secondary productivity in the Baltic Sea. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 68:85–99

Loogman JG (1982) Influence of photoperiodicy on algal growth kinetics. Ph.D. University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Magaletti E, Urbani R, Sist P, Ferrari CR, Cicero AM (2004) Abundance and chemical characterization of extracellular carbohydrates released by the marine diatom Cylindrotheca fusiformis under N- and P- limitation. Eur J Phycol 39:133–142

Manners DJ, Ryley JF, Stark JR (1966) Studies on the metabolism of the protozoa – the molecular structure of the reserve polysaccharide from Astasia ocellata. Biochem J 101:323–327

Marañón E, Cermeño P, Fernández E, Rodríguez J, Zabala L (2004) Significance and mechanisms of photosynthetic production of dissolved organic carbon in a coastal eutrophic ecosystem. Limnol Oceanogr 49:1652–1666

Mari X, Rassoulzadegan F, Brussaard CPD, Wassmann P (2005) Dynamics of transparent exopolymeric particles (TEP) production by Phaeocystis globosa under N- or P-limitation: a controlling factor of the retention/export balance. Harmful Algae 4:895–914

Martin JH, Gordon RM, Fitzwater SE (1990) Iron in Antarctic Waters. Nature 345:156–158

Mathot S, Smith WO, Carlson CA, Garrison DL, Gowing MM, Vickers CL (2000) Carbon partitioning within Phaeocystis antarctica (Prymnesiophyceae) colonies in the Ross Sea, Antarctica. J Phycol 36:1049–1056

Matrai PA, Vernet M, Hood R, Jennings A, Brody E, Saemundsdottir S (1995) Light-dependence of carbon and sulfur production by polar clones of the genus Phaeocystis. Mar Biol 124:157–167

Metaxatos A, Panagiotopoulos C, Ignatiades L (2003) Monosaccharide and aminoacid composition of mucilage material produced from a mixture of four phytoplanktonic taxa. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 294:203–217

Moestrup O (1979) Identification by electron microscopy of marine nanaoplankton from New Zealand, including the description of four new species. N Z J Bot 17:61–95

Mopper K, Kieber DJ (2001) Marine photochemistry and its impact on carbon cycling. In: De Mora S, Demers S, Vernet M (eds) The effect of UV radiation in the marine environment. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, pp 102–129

Mopper K, Zhou XL, Kieber RJ, Kieber DJ, Sikorski RJ, Jones RD (1991) Photochemical degradation of dissolved organic-carbon and its impact on the oceanic carbon-cycle. Nature 353:60–62

Moran MA, Zepp RG (1997) Role of photoreactions in the formation of biologically labile compounds from dissolved organic matter. Limnol Oceanogr 42:1307–1316

Myklestad SM (1974) Production of carbohydrates by marine planktonic diatoms. I. Comparison of nine different species in culture. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 15:261–274

Myklestad SM (1978) Beta-1,3-glucans in diatoms and brown seaweeds. In: Hellebust JA, Craigie JS (eds) Handbook of phycological methods. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 133–141

Myklestad SM (1988) Production, chemical structure, metabolism, and biological function of the (1,3)-linked, beta-D-glucans in diatoms. Biol Oceanogr 6:313–326

Myklestad SM, Haug A (1972) Production of carbohydrates by the marine diatom Chaetoceros affinis var. Willei (Gran) Hustedt. II Preliminary investigation of the extracellular polysaccharide. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 9:137–144

Myklestad SM, Skanoy E, Hestmann S (1997) A sensitive and rapid method for analysis of dissolved mono- and polysaccharides in seawater. Mar Chem 56:279–286

Nagata T (2000) Production mechanisms of dissolved organic matter. In: Kirchman DL (ed) Microbial ecology of the oceans. Wiley-Liss, pp 121–152

Nejstgaard JC, Tang KW, Steinke M, Dutz J, Antajan E, Long JD (2007) Zooplankton grazing on Phaeocystis: a critical review and future challenges. Biogeochemistry this issue

Orellana MV, Verdugo P (2003) Ultraviolet radiation blocks the organic carbon exchange between the dissolved phase and the gel phase in the ocean. Limnol Oceanogr 48:1618–1623

Orellana MV, Lessard EJ, Dycus E, Chin WC, Foy MS, Verdugo P (2003) Tracing the source and fate of biopolymers in seawater: application of an immunological technique. Mar Chem 83:89–99

Osinga R, De Vries KA, Lewis WE, Van Raaphorst W, Dijkhuizen L, Van Duyl FC (1997) Aerobic degradation of phytoplankton debris dominated by Phaeocystis sp. in different physiological stages of growth. Aquat Microb Ecol 12:11–19

Painter TJ (1983) Algal polysaccharides. In: Aspinall GO (ed) The polysaccharides. Academic Press, New York, pp 195–285

Parke M, Green JC, Manton I (1971) Observations on the fine structure of zoids of the genus Phaeocystis (Haptophyceae). J Mar Biol Assoc UK 51:927–941

Passow U, Wassmann P (1994) On the trophic fate of Phaeocystis pouchetii (Hariot): IV. The formation of marine snow by P. pouchetii. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 104:153–161

Paulsen BS, Myklestad SM (1978) Structural studies of the reserve glucan produced by the marine diatom Skeletonema costatum. Carbohydr Res 62:386–388

Peperzak L, Colijn F, Vrieling EG, Gieskes WWC, Peeters JCH (2000) Observations of flagellates in colonies of Phaeocystis globosa (Prymnesiophyceae); a hypothesis for their position in the life cycle. J Plankt Res 22:2181–2203

Percival E (1970) Algal polysaccharides. In: Pigman W, Horton D (eds) The carbohydrates, vol IIB. Academic Press, New York, pp 541–544

Post AF, Dubinsky Z, Wyman K, Falkowski PG (1985) Physiological-responses of a marine planktonic diatom to transitions in growth irradiance. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 25:141–149

Putt M, Miceli G, Stoecker DK (1994) Association of bacteria with Phaeocystis sp. in McMurdo Sound, Antarctica. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 105:179–189

Reichenbach H, Dworkin M (1991) The order Cytophagales. In: Balows A, Truber HG, Dworkin M, Harder W, Schleifer KH (eds) The prokaryotes. Springer-Verlag, New York, pp 356–379

Renn DW (1997) Purified curdlan and its hydroxyalkyl derivatives: preparation, properties and applications. Carbohydr Pol 33:219–225

Riebesell U, Reigstad M, Wassmann P, Noji T, Passow U (1995) On the trophic fate of Phaeocystis pouchetii (Hariot): VI. Significance of Phaeocystis-derived mucus for vertical flux. Neth J Sea Res 33:193–203

Riegman R, Van Boekel W (1996) The ecophysiology of Phaeocystis globosa: a review. J Sea Res 35:235–242

Rousseau V, Mathot S, Lancelot C (1990) Calculating carbon biomass of Phaeocystis sp. from microscopic observations. Mar Biol 107:305–314

Rousseau V, Vaulot D, Casotti R, Cariou V, Lenz J, Gunkel J, Baumann MEM (1994) The life cycle of Phaeocystis (Prymnesiophyceae): evidence and hypotheses. J Mar Syst 5:23–40

Rousseau V, Becquevort S, Parent JY, Gasparini S, Daro MH, Tackx M, Lancelot C (2000) Tropic efficiency of the planktonic food web in a coastal ecosystem dominated by Phaeocystis colonies. J Sea Res 43:357–372

Sannigrahi P, Ingall ED, Benner R (2005) Cycling of dissolved and particulate organic matter at station Aloha: insights from C-13 NMR spectroscopy coupled with elemental, isotopic and molecular analyses. Deep-Sea Res I 52:1429–1444

Schoemann W, Becquevort S, Stefels J, Rousseau W, Lancelot C (2005) Phaeocystis blooms in the global ocean and their controlling mechanisms: a review. J Sea Res 53:43–66

Seuront L, Lacheze C, Doubell MJ, Seymour JR, Van Dongen-Vogels V, Newton K, Alderkamp AC, Mitchell JG (2007) The influence of Phaeocystis globosa on microscale spatial patterns of chlorophyll a and bulk-phase seawater viscosity. Biogeochemistry this issue

Sharp JH (1977) Excretion of organic matter by marine phytoplankton: do healthy cells do it? Limnol Oceanogr 22:381–399

Smith DC, Simon M, Alldredge AL, Azam F (1992) Intense hydrolytic enzyme activity on marine aggregates and implications for rapid particle dissolution. Nature 359:139–141

Smith DC, Steward GF, Long RA, Azam F (1995) Bacterial mediation of carbon fluxes during a diatom bloom in a mesocosm. Deep Sea Res II 42:75–97

Smith WO, Codispoti LA, Nelson DM, Manley T, Buskey EJ, Niebauer HJ, Cota GF (1991) Importance of Phaeocystis blooms in the high-latitude ocean carbon cycle. Nature 352:514–516

Smith WO, Carlson CA, Ducklow HW, Hansell DA (1998) Growth dynamics of Phaeocystis antarctica-dominated plankton assemblages from the Ross Sea. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 168:229–244

Solomon CM, Lessard EJ, Keil RG, Foy MS (2003) Characterization of extracellular polymers of Phaeocystis globosa and P. antarctica. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 250:81–89

Stoderegger K, Herndl GJ (1998) Production and release of bacterial capsular material and its subsequent utilization by marine bacterioplankton. Limnol Oceanogr 43:877–884

Tang KW, Jakobsen HH, Visser AW (2001) Phaeocystis globosa (Prymnesiophyceae) and the planktonic food web: feeding, growth, and trophic interactions among grazers. Limnol Oceanogr 46:1860–1870

Teira E, Pazo MJ, Quevedo M, Fuentes MV, Niell FX, Fernández E (2003) Rates of dissolved organic carbon production and bacterial activity in the eastern North Atlantic Subtropical Gyre during summer. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 249:53–67

Thingstad TF, Billen G (1994) Microbial degradation of Phaeocystis material in the water column. J Mar Syst 5:55–66

Thingstad TF, Hagström A, Rassoulzadegan F (1997) Accumulation of degradable DOC in surface waters: is it caused by a malfunctioning microbial loop? Limnol Oceanogr 42:398–404

Underwood GJC, Boulcott M, Raines CA, Waldron K (2004) Environmental effects on exopolymer production by marine benthic diatoms: dynamics, changes in composition, and pathways of production. J Phycol 40:293–304

Vadstein O, Jensen A, Olsen Y, Reinertsen H (1988) Growth and phosphorus status of limnetic phytoplankton and bacteria. Limnol Oceanogr 33:489–503

Van Boekel WHM (1992) Phaeocystis colony mucus components and the importance of calcium ions for colony stability. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 87:301–305

Van Boekel WHM, Hansen FC, Riegman R, Bak RPM (1992) Lysis-induced decline of a Phaeocystis spring bloom and coupling with the microbial foodweb. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 81:269–276

Van den Hoek C, Jahns HM, Mann DG (1993) Algen. Georg Thieme Verlag Stuttgard, New York

Van Oijen T, Van Leeuwe MA, Gieskes WWC (2003) Variation of particulate carbohydrate pools over time and depth in a diatom-dominated plankton community at the Antarctic Polar Front. Polar Biol 26:195–201

Van Oijen T, Van Leeuwe MA, Gieskes WWC, De Baar HJW (2004a) Effects of iron limitation on photosynthesis and carbohydrate metabolism in the Antarctic diatom Chaetoceros brevis (Bacillariophyceae). Eur J Phycol 39:161–171

Van Oijen T, Van Leeuwe MA, Granum E, Weissing FJ, Bellerby RGJ, Gieskes WWC, De Baar HJW (2004b) Light rather than iron controls photosynthate production and allocation in Southern Ocean phytoplankton populations during austral autumn. J Plankt Res 26:885–900

Van Oijen T, Veldhuis MJW, Gorbunov MY, Nishioka J, Van Leeuwe MA, De Baar HJW (2005) Enhanced carbohydrate production by Southern Ocean phytoplankton in response to in-situ iron fertilisation. Mar Chem 93:33–52

Van Rijssel M, Hamm CE, Gieskes WWC (1997) Phaeocystis globosa (Prymnesiophyceae) colonies: hollow structures built with small amounts of polysaccharides. Eur J Phycol 32:185–192

Van Rijssel M, Janse I, Noordkamp DJB, Gieskes WWC (2000) An inventory of factors that affect polysaccharide production by Phaeocystis globosa. J Sea Res 43:297–306

Vårum KM, Kvam BJ, Myklestad SM (1986) Structure of a food-reserve beta-D-glucan produced by the haptophyte alga Emiliania huxleyi (Lohmann) Hay and Mohler. Carbohydr Res 152:243–248

Veldhuis MJW, Admiraal W (1985) Transfer of photosynthetic products in gelatinous colonies of Phaeocystis pouchetii (Haptophyceae) and its effect on the measurement of excretion rate. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 26:301–304

Veldhuis MJW, Admiraal W, Colijn F (1986a) Chemical and physiological-changes of phytoplankton during the spring bloom, dominated by Phaeocystis pouchetii (Haptophyceae) – observations in Dutch coastal waters of the North Sea. Neth J Sea Res 20:49–60

Veldhuis MJW, Colijn F, Venekamp LAH (1986b) The spring bloom of Phaeocystis pouchetii (Haptophyceae) in Dutch coastal waters. Neth J Sea Res 20:37–48

Veldhuis MJW, Brussaard CPD, Noordeloos AAM (2005) Living in a Phaeocystis colony: a way to be a successful algal species. Harmful Algae 4:841–858

Verdugo P, Alldredge AL, Azam F, Kirchman DL, Passow U, Santschi PH (2004) The oceanic gel phase: a bridge in the DOM-POM continuum. Mar Chem 92:67–85

Verity PG, Villareal TA, Smayda TJ (1988) Ecological investigations of blooms of colonial Phaeocystis pouchetii. I Abundance, biochemical composition and metabolic rates. J Plankt Res 10:219–248

Verity PG, Smayda TJ, Sakshaug E (1991) Photosynthesis, excretion, and growth rates of Phaeocystis colonies and solitary cells. Polar Res 10:117–128

Wassmann P (1994) Significance of sedimentation for the termination of Phaeocystis blooms. J Mar Syst 5:81–100

Wassmann P, Vernet M, Mitchell BG, Rey F (1990) Mass sedimentation of Phaeocystis pouchetii in the Barents Sea. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 66:183–196

Wassmann P, Reigstad M, Oygarden S, Rey F (2000) Seasonal variation in hydrography, nutrients, and suspended biomass in a subarctic fjord: applying hydrographic features and biological markers to trace water masses and circulation significant for phytoplankton production. Sarsia 85:237–249

Weisse T, Scheffel-Möser U (1990) Growth and grazing loss rates in single-celled Phaeocystis sp. (Prymnesiophyceae). Mar Biol 106:153–158

Zingone A, Chretiennot-Dinet MJ, Lange M, Medlin L (1999) Morphological and genetic characterization of Phaeocystis cordata and P. jahnii (Prymnesiophyceae), two new species from the Mediterranean Sea. J Phycol 35:1322–1337

Acknowledgements

We thank M.J.E.C. van der Maarel and H. Helmers for the analysis of the viscosity of laminarin. L. Seuront is acknowledged for stimulating comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Alderkamp, AC., Buma, A.G.J. & van Rijssel, M. The carbohydrates of Phaeocystis and their degradation in the microbial food web. Biogeochemistry 83, 99–118 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-007-9078-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-007-9078-2