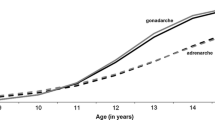

We report heritabilities for individual differences in female pubertal development at the age of 12. Tanner data on breast and pubic hair development in girls and data on menarche were obtained from a total of 184 pairs of monozygotic and dizygotic twins. Genetic correlations were estimated to determine to what extent the same genes are involved in different aspects of physical development in puberty. A Bayesian estimation approach was taken, using Markov-chain Monte Carlo simulation to estimate model parameters. All three phenotypes were to a significant extent heritable and showed high genetic correlations, suggesting that a common set of genes is involved in the timing of puberty in general. However, gonadarche (menarche and breast development) and adrenarche (pubic hair) are affected by different environmental factors, which does not support the three phenotypes to be regarded as indicators of a unitary physiological factor.

Similar content being viewed by others

REFERENCES

Bartels M., Rietveld M. J. H., Van Baal G. C. M., Boomsma D. I. (2002). Genetic and environmental influences on the development of intelligence. Behav. Genet. 32:237–249

Boomsma D. I., Vink J. M., Beijsterveldt C. E. M., De Geus E. J. C., Beem A. L., Mulder E. J. C. M., Riese H., et al. (2002). Netherlands Twin Register: A focus on longitudinal research. Twin Res. 5:401–406

Coleman L., Coleman J. (2002). The measurement of puberty: A review. J. Adolescence 25:535–550

Comings D. E., Muhleman D., Johnson J. P., MacMurray J. P. (2002). Parent–daughter transmission of the androgen receptor gene as an explanation of the effect of father absence on age of menarche. Child Dev. 73:1046–1051

Cowles M. K. (2004). Review of WinBUGS 1.4. Am. Stat. 58:330–336

Crittenden L. B. (1961). An interpretation of familial aggregation based on multiple genetic and environmental factors. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 91:769–780

Da Silva Faria T., Fonte Ramos C., Sampaio F. J. B. (2004). Puberty onset in the female offspring of rats submitted to protein or energy restricted diet during lactation. J. Nutr. Biochem. 15:123–127

Dorn L. D., Rotenstein D. (2004). Early puberty in girls: The case of premature adrenarche. Wom. Health Iss. 14:177–183

Eaves L. J., Erkanli A. (2003). Markov Chain Monte Carlo approaches to analysis of genetic and environmental components of human developmental change and G X E interaction. Behav. Genet. 33:279–299

Eaves L., Silberg J., Foley D., Bulik C., Maes H., Erkanli A., Angold A., Costello E. J., Worthman C. (2004). Genetic and environmental influences on the relative timing of pubertal change. Twin Res. 7:471–481

Falconer D.S. (1965). The inheritance of liability to certain diseases, estimated from the incidence among relatives. Ann. Hum. Genet. 29:51–71

Fischbein S. (1977). Intra-pair similarity in physical growth of monozygotic and of dizygotic twins during puberty. Ann. Hum. Biol. 4:417–430

Frisch R. E. (1996). The right weight: Body fat, menarche, and fertility. Nutrition 12:452–453

Gelman A., Carlin J. B., Stern H. S., Rubin D. B. (2004). Bayesian Data Analysis. (2nd ed.). Boca Raton FL, Chapman & Hall/ CRC

Gilks W. R., Richardson S., Spiegelhalter D. J. (1996). Markov Chain Monte Carlo Methods in Practice. Boca Raton FL, CRC Press

Groot A. S., de Sonneville L. M. J., Stins J. F., Boomsma D. I. (2004). Familial influences on sustained attention and inhibition in preschoolers. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 45:306–314

Herman-Giddens M. E., Kaplowitz P. B., Wasserman R. (2004). Navigating the recent articles on girls’ puberty in Pediatrics: What do we know and where do we go from here? Pediatrics 113:911–917

Herman-Giddens M. E., Slora E. J., Wasserman R. C., Bourdony C. J., Bhapkar M. V., Koch G. G., Hasemeier C.M. (1997). Secondary sexual characteristics and menses in young girls seen in office practice: A study from the pediatric research in office settings network. Pediatrics 99:505–512

Johansson T., Ritzen E. M. (2005). Very long-term follow-up of girls with early and late menarche. Endocr. Dev. 8:126–136

Jorm A. F., Christensen H., Rodgers B., Jacomb P. A., Easteal S. (2004). Association of adverse childhood experiences, age of menarche, and adult reproductive behavior: Does the androgen receptor gene play a role? Am. J. Med. Genet. B 125:105–111

Loesch D. Z., Hopper J. L., Rogucka E., Huggins R. M. (1995). Timing and genetic rapport between growth in skeletal maturity and height around puberty: similarities and differences between girls and boys. Am. J. of Hum. Genet. 56:753–759

Lynch M., Walsh B. (1998). Genetics and Analysis of Quantitative Traits. Sunderland MA, Sinauer

Marshall W. A., Tanner J. M. (1969). Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Arch. Dis. Child. 44:291–303

Maestripieri D., Roney J. R., DeBias N., Durante K. M., Spaepen G. M. (2004). Father absence, menarche and interest in infants among adolescent girls. Dev. Sci. 7:560–566

Meyer J. M., Eaves L. J., Heath A. C., Martin N. G. (1991). Estimating genetic influences on the age-at-menarche: a survival analysis approach. Am. J. Med. Genet. 39:148–154

Muinck Keizer-Schrama S. M. P. F., Mul D. (2001). Trends in pubertal development in Europe. Hum. Reprod. Update 7:287–291

Mustanski B. S., Viken R. J., Kaprio J., Pulkkinen L., Rose R. J. (2004). Genetic and environmental influences on pubertal development: Longitudinal data from Finnish twins at ages 11 and 14. Dev. Psychol. 40:1188–1198

Ojeda S. R., Hill J., Hill D. F., Costa M. E., Tapia V., Cornea A., Ma Y. J. (1999). The Oct-2 POU domain gene in the neuroendocrine brain: A transcriptional regulator of mammalian puberty. Endocrinology 140:3774–3789

Ojeda S. R., Ma Y. J., Lee B. J., Prevot V. (2000). Glia-to-neuron signaling and the neuroendocrine control of female puberty. Recent Prog. Horm. Res. 55:197–223; discussion 223–4

Palmert M. R., Hirschhorn J. N. (2003). Genetic approaches to stature, pubertal timing, and other complex traits. Mol. Genet. Metab. 80:1–10

Palmert M. R., Boepple P. A. (2001). Variation in the timing of puberty: Clinical spectrum and genetic investigation. J. Clin. Endocr. Metab. 86:2364–2368

Parent A. S., Teilmann G., Juul A., Skakkebaek N. E., Toppari J., Bourguignon J. P. (2003). The timing of normal puberty and the age limits of sexual precocity: Variations around the world, secular trends, and changes after migration. Endocr. Rev. 24:668–693

Sklad M. (1977). The rate of growth and maturing of twins. Acta Genet. Med. Gemel. 26:221–237

Styne D. M. (2004). Puberty, obesity and ethnicity. Trends Endocrin. Met. 15:472–478

Veening M. A., van Weissenbruch M. M., Roord J. J., Delemarre-Van Waal H. A. (2004). Pubertal development in children born small for gestational age. J. Pediatr. Endocr. Met. 17:1497–1505

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grants from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research NWO, numbers 575-25-012, 904-57-94, and 051-02-060,668-772. AS was supported by the Evangelischer Entwicklungsdienst, Bonn, Germany.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

APPENDIX

APPENDIX

Estimating Heritabilities and Genetic and Environmental Correlations using MCMC

The phenotypes were measured using ordinal scales. In order to estimate heritabilities and genetic and environmental correlations, we assumed three underlying latent normally distributed variables using the so-called threshold model (Crittenden, 1961; Falconer, 1965; Lynch and Walsh, 1998). Latent traits were decomposed into additive genetic (A), shared environmental (C) and nonshared environmental (F) parts. In order to implement the model in WinBUGS, it is most efficient to parametrise the model in such a way that the nonshared environmental vector F is further decomposed into vectors U and E, where U incorporates nonshared environmental correlations between the traits and E is a vector with uncorrelated coordinates:

Here, the first index i denotes the phenotype and the second j the individual in a twin pair. More precisely, we modelled the nonshared environmental vector as F=U + E with U and E independent and marginally distributed as follows:

The parameters in this specification are not individually identifiable from the data, but can be used to specify a prior distribution on the model used. The Bayesian approach yields a posterior distribution for all parameters, but we only report the part of the posterior distribution that concerns identifiable parameters, as the remaining part of the posterior is a result of prior specification only, without intervention of the data. For instance, the unshared environmental coefficient of correlation between the latent variables for the first and second phenotypes is given by

Thus, although the parameters χ,ρ7,δ,γ, and κ are individually not identifiable given the data, a function of them (ρ) is. Using the MCMC method it is straightforward to calculate the posterior distribution for this function from the sampled values of the full parameter set.

The vectors for the additive genetic effects (A) and shared environmental effects (C) were modelled in the usual way:

for MZ twin pairs and

for DZ twin pairs, and

Here, inference is more straightforward. For instance, ρ1 stands for the correlation between the additive genetic effects on the first and second latent trait and ρ4 stands for the correlation between the shared environmental effects on the first and second latent trait.

Implementation of the model in WinBUGS requires the specification of prior distributions for the parameters as well as the conditional distribution of the observed data given the model parameters. Given the genetic and non-genetic random effects A iik C ik and U ijk for both individual twins from a twin pair k, the probability of a particular phenotypic state in a twin is not dependent on the respective phenotype in her co-twin nor on the other phenotypes. The conditional probability of a response in the first category for a phenotype is then

with Y ijk denoting the the i-th phenotype in the j-th twin from the k-th twin pair, Φ(.) denoting the cumulative standard normal distribution function and t i1 denoting the first threshold for the i-th phenotype. For the conditional probability of observing a response in the second category we have

All other conditional probabilities can be written out analogously. These conditional probabilities can be used in a Gibbs sampling algorithm as implemented in WinBUGS in order to estimate the thresholds and other parameters of interest. Its implementation in WinBUGS consists of a rather large script. Contact SvdB or AS for a copy.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

van den Berg, S.M., Setiawan, A., Bartels, M. et al. Individual Differences in Puberty Onset in Girls: Bayesian Estimation of Heritabilities and Genetic Correlations. Behav Genet 36, 261–270 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-005-9022-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-005-9022-y