Abstract

In this article I argue for rule-based, non-monotonic theories of common law judicial reasoning and improve upon one such theory offered by Horty and Bench-Capon. The improvements reveal some of the interconnections between formal theories of judicial reasoning and traditional issues within jurisprudence regarding the notions of the ratio decidendi and obiter dicta. Though I do not purport to resolve the long-standing jurisprudential issues here, it is beneficial for theorists both of legal philosophy and formalizing legal reasoning to see where the two projects interact.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

There is a controversy in legal philosophy regarding the possibility and nature of precedential constraint, see (Alexander and Sherwin 2008; Schauer 2008). In that realm I have argued that precedential constraint is possible and its nature is best understood through the prioritized defaults of (Horty and Bench-Capon 2012) in my (2014b).

More specifically, the notions of ratio and dicta favor an approach that extracts a rule or rules from an individual case, as the definitions in the text make clear.

In earlier formulations, such as Horty (2004), the antecedent of the rule was the set of all reasons for the prevailing party. The more recent and improved version allows the antecedent of the rule to be a proper subset of the reasons for the prevailing party, allowing the improved theory to go beyond a fortiori reasoning. The determination of which reasons compose the antecedent is part of the process of extracting a rule from a case. That process is independent of the theory.

I ignore the subtleties of contract law remedies in these examples for ease of exposition.

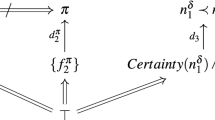

Notice that she can distinguish on the basis that R d2 combined with R d1 tilts the scale toward the defendant, which yields Rule2. She could also distinguish on the basis that R d2 is so potent that it alone outweighs R p1 . This would yield a different rule, namely, {R d2 } → D☺. The weighing introduced by the second option is {R d2 } > {R p1 }. The first approach is thus a more cautious method of distinguishing.

Some have argued against this theory on the grounds that there are always novel sets of reasons for both parties in each case. See (Rigoni 2014a) for a response. There are also questions about aggregating relative weights. For example the > relation is not transitive, so it does not follow from R d1 > R p1 , R p2 > R d1 , and R p1 > R d2 , that R p2 > R d2 . These issues are discussed in (Horty and Bench-Capon 2012, p. 199; Horty 2011, p. 17; Rigoni 2014b, Chapter 3).

R d3 is highly simplified, as equitable holdings typically involve weighing a number of facts. For simplification I compress all the pro-defendant reasons with respect to equitable indemnity into one reason.

For example, Kritzer and Richards (2003) argue that Lemon marked the beginning of an empirically measurable, distinct epoch in how the Supreme Court decided establishment-clause cases.

One might object that this and the following examples use too coarse-grained a characterization of the relevant reasons. Instead, the objection goes, we should adopt an approach that individuates facts that lead to the conclusion that there is a secular legislative purpose. I address this issue later in this section.

For explanation see (School Dist.of Abington Twp., Pa. v. Schempp 1963, p. 223–225).

It also raises the question of why not take the Walz citation seriously as well and then just make Lemon an entrenchment of that rule. But I am ignoring that question here. See supra at Sect. 4.2.

Once this is adopted, R p n and R d n will no longer represent reasons that obtain in the case. Instead, they will represent potential reasons. This is unproblematic since the theory assumes that the reasoner has already determined the sets of obtaining pro-plaintiff and pro-defendant reasons that obtain independently of her determination of the rules in the case. I refer to these potential reasons simply as “reasons” in what follows.

Rule3 imposes the familiar weighing where R p3 outweighs all the pro-defendant reasons present in Lemon.

This is basically the approach taken by the IBP + HB-C hybrid approach discussed in Sect. 5.3.

See infra, Sect. 5.3 for a discussion of exceptions to the Lemon rules.

See, for example, Marshall's dissent in Stencel Aero Eng’g Corp v. U.S. (1977).

One could go further and stipulate that the three prongs always have equal weight. I do not explore this possibility.

There is another issue lurking here, which I ignore in this chapter, namely, what if the past cases involve businesses that are between 20 and 30 feet from the respective homes? How do would we get from that to a conclusion about businesses 15 feet from homes? See (Rigoni 2014a) for further discussion.

I use this strategy because, as will be seen, it prevents S-rules from chaining. It might be best to allow S-Rules to chain, but I adopt the most conservative possible strategy here. I discuss loosening the reins in my (2014b, Chapter 3).

I am here thinking of instances where a past case causes one to notice a previously unnoticed reason, not anything involving the application of the rules.

There is a different concern that the reasons involved in the excessive entanglement prong and the primary purpose prong are the same, and that the reasons that establish no primary purpose of advancing or inhibiting religion are exactly those that establish excessive entanglement. This is what the Court would later call a “Catch 22” argument (Bowen v. Kendrick 1988, pp. 615–616). I ignore this flaw with the reasoning in Lemon and operate as if the test is coherent.

See Arizona v. Johnson (2009) for a thorough (and unanimously approved) discussion of the cases fleshing out the Terry Rule.

This ignores S-Rules, but the parallel statement for when they are binding is obvious.

One might ask why judges include reasons favoring the prevailing party that are not in the antecedent of the rule used to decide the case. I think there are a number of mutually consistent explanations. First, these reasons may matter to other decisions made in the opinion, such as the setting of damages or a decision to award attorney’s fees. Second, these reasons may be needed to provide a coherent narrative for the facts of the case. The importance of such narratives is discussed in (Bex et al. 2011). For example, that the plaintiff and defendant in a contract case are related may not matter for the resolution of a contract dispute, but it may explain why these parties contracted with each other, which fills out the narrative of negotiation, contract, and breach. Third, giving a relatively complete account of the facts is a customary part of opinion writing in common law jurisdictions. The exact influence of dicta of this sort is beyond the scope of this project. However, an interested reader can use the following exercise to see how pervasive such dicta are: pick an illustration from any Restatement of the law with the opinion upon which it is based. The illustrations are single paragraph narratives involving “A” and “B” that demonstrate the rule of the case. The actual opinion is, of course, much longer and more detailed. One will find a number of reasons for each party that are omitted from the illustration.

In Roth’s case this difference may be due to differences in the legal systems on which we are focused. I am focused on the U.S. legal system, which gives trial courts fact finding discretion, meaning such findings are unlikely to be overturned on appeal. Moreover, the U.S. system permits juries to make a number of determinations that seem to fall within Roth’s view of precedent. Juries are not subject to precedential constraint and are not supposed to even be influenced by past cases. Roth is looking at the Dutch legal system, where there are no juries and appellate courts review factual findings de novo, meaning an appeal is essentially a fresh trial (Nijboer 2007, p. 399, 409). Such a system seems friendlier to precedents that govern determinations on the factual end of the spectrum.

This is perhaps the flip side of Branting’s (1993) idea that the theory behind a case must be incorporated into the precedent it establishes.

In other work by Atkinson and Bench-Capon acknowledge that inferences from evidence to facts are typically performed by the jury and the “style of argument is rather different” (Al-Abdulkarim et al. 2014, p. 63). However they did not attempt to explain the effect this would have on the earlier ASPIC+ proposal in Atkinson et al. (2013).

A similar argument, in a Wittgensteinian vein, can be made regarding relevance. Atkinson et al. do not start by considering cases as mere or bare facts, but relevant facts. The dimensions determine which facts are relevant to the case as well as the polarity of these facts (which makes them seem more like low level factors than facts, but that is beside the point). Yet parties can also argue about the dimensions that are relevant to the case. Post might have argued that his advanced age entitled him deference, for he was 2 years older than Pierce (Ernst 2009), thereby attempting to make the dimension of age applicable. Pierson would of course resist. To capture their argument we must descend yet another level down the hierarchy and use facts to decide which dimensions are relevant. To make this tractable, we must represent only the facts relevant to this question, but one could dispute the relevance of these facts, so down the rabbit hole we go. However, as Wittgenstein would point out, we do not fall into the rabbit hole. Although it is logically possible to continually dispute the relevance of some facts based on further facts the relevance of which is then disputed, we do not do this. Just why we do not is a difficult question, but not one that undermines theorizing legal reasoning.

This issue, or a strikingly similar one, arises in philosophical disputes regarding the nature of law. In the inclusive positivist tradition, Kelsen writes, “just as everything King Midas touched turned into gold, everything to which law refers becomes law” (Kelsen 1967, p. 161). Exclusive positivists reject this notion (Raz 1979; Shapiro 2013), arguing for a distinct demarcation between legal and extra-legal norms.

This discussion is indebted to the suggestions of an insightful anonymous reviewer.

References

Al-Abdulkarim L, Atkinson K, Bench-Capon T (2014) Abstract dialectical frameworks for legal reasoning. In: Hoekstra R (ed) Proceedings of 27th international conference on legal knowledge and information systems (JURIX 2014). IOS Press, Amesterdam, Netherlands, pp 61–70

Alchourron CE (1996) On law and logic. Ratio Juris 9(4):331–348

Aleven V (1997) Teaching cased-based argumentation through a model and examples. University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh

Alexander L, Sherwin E (2008) Demystifying legal reasoning. Cambridge University Press, New York

American Law Institute (1979) Restatement (second) of torts

Antonelli G (1999) A directly cautious theory of defeasible consequence for default logic via the notion of general extension. Artif Intell 109(1–2):71–109

Arizona v. Johnson 555 US 323 (2009)

Ashley KD (1990) Molding legal argument: reasoning with cases and hypotheticals. The MIT Press, Cambridge

Ashley KD (1991) Reasoning with cases and hypotheticals in hypo. Int J Man Mach Stud 34:753–796

Atkinson K, Bench-Capon T, Prakken H, Wyner A, Wyner A, Peters W, Katz D (2013) Argumentation schemes for reasoning about factors with dimensions. In: Ashley K (ed) Proceedings of 26th international conference on legal knowledge and information systems (JURIX 2013). IOS Press, Amesterdam, Netherlands, pp 39–48

Bench-Capon T, Sartor G (2003) A model of legal reasoning with cases incorporating theories and values. Artif Intell 150(1–2):97–143

Bex F, Bench-Capon TJM, Verheij B (2011) What makes a story plausible? The need for precedents. Legal Knowledge and Information Systems, JURIX 2011: the twenty-fourth annual conference, 23–32

Board of Ed. Of Central School Dist. 1 v. Allen 392 U.S. 236 (1968)

Board of Ed. of Kiryas Joel Village School Dist. v. Grumet 512 U.S. 687 (1994)

Branting K (1991) Reasoning with portions of precedents. In: Proceedings of the 3rd international conference on AI and Law, 145–154

Branting K (1993) A reduction-graph model of ratio decidendi. In: Proceedings of the 4th international conference on AI and Law, 40–49

Brewer S (1996) Exemplary reasoning: semantics, pragmatics, and the rational force of legal argument by analogy. Harv Law Rev 109(5):923–1028

Brewka G (1991) Nonmonotonic reasoning: logical foundations of commonsense. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Bruninghaus S, Ashley K (2003) Predicting outcomes of case based legal arguments. In: Proceedings of the 9th international conference on artificial intelligence and law, 233–42

Choper JH (1987) The establishment clause and aid to parochial schools—an update. Calif Law Rev 75:5–15

Cox KM (1984) The Lemon test soured: the supreme court’s new establishment clause analysis. Vanderbilt Law Rev 37:1176–1205

Cutter v. Wilkinson 544 US 709 (2005)

Dworkin R (1986) Law’s empire. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Ernst D (2009) Pierson v. post: the protagonists. Retrieved from http://legalhistoryblog.blogspot.com/2009/07/pierson-v-post-protagonists.html on 1 Jan 2015

Esbeck CH (1989) The Lemon test: should it be retained, reformulated or rejected. Notre Dame J Leg Ethics Pub Policy 4:513

Garner BA (ed) (2004) Black’s law dictionary, 8th edn. West, St. Paul

Giannella DA (1971) Lemon and Tilton: the bitter and the sweet of church-state entanglement. Supreme Court Rev 1971:147–200

Goodhart AL (1930) Determining the ratio decidendi of a case. Yale Law J, 161–183

Hart HLA (1948) The ascription of responsibility and rights. Proc Aristot Soc 49:171–194

Hart HLA (1958) Positivism and the separation of law and morals. Harv Law Rev 71(4):593–629

Hart HLA (1961) The concept of law. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Horty JF (2004) The result model of precedent. Leg Theory 10:19–31

Horty JF (2011) Rules and reasons in the theory of precedent. Legal Theory 17(01):1–33

Horty JF (2012) Reasons as defaults. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Horty JF, Bench-Capon TJM (2012) A factor-based definition of precedential constraint. Art Intell Law 20(2):181–214

Kahle LM (2005) Making Lemon-aid from the supreme court’s Lemon: why current establishment clause juriprudence should be replaced by a modified coercion test. S Diego Law Rev 42:349

Kelsen H (1967) Pure theory of law. (Knight M, Trans.). University of California Press, Berkeley

Kritzer HM, Richards MJ (2003) Jurisprudential regimes and supreme court decision making: the lemon regime and establishment clause cases. Law Soc Rev 37(4):827–840

Lamond G (2005) Do precedents create rules? Leg Theory 11(01):1–26

Lee v. Weisman 505 U.S. 577 (1992)

Lemon v. Kurtzman 403 U.S. 602 (1971)

Lewis JM, Vild ML (1989) Controversial twist of lemon: the endorsement test as the new establishment clause standard. Notre Dame Law Rev 65:671

Lindahl L, Odelstad J (2006) Intermediate concepts in normative systems. In: Deontic logic and artificial normative systems, 8th international workshop on deontic logic in computer science, pp. 187–200

Lucas JD (1983) The direct and collateral estoppel effects of alternative holdings. Univ Chic Law Rev 50(2):701–730

McCarthy J (1980) Circumscription—a form of non-monotonic reasoning. Artif Intell 13:27–39

Meyers PJ (1999) Lemon is alive and kicking: using the lemon test to determine the constitutionality of prayer at high school graduation ceremonies. Valpso Univ Law Rev 34:231

Miller v. California 413 U.S. 15 (1973)

New York v. Ferber 458 U.S. 747 (1982)

Nijboer JF (2007) The criminal justice system. In: Hondius E, Chorus J, Gerver P-H (eds) Introduction to Dutch law, 4th edn. Kluwer Law International

Paulsen MS (1992) Lemon is dead. Case West Law Rev 43:795

Pennsylvania v. Mimms 434 U.S. 106 (1977)

Police Department v. Mosley 408 U.S. 92 (1972)

Prakken H, Sartor G (1996) A dialectical model of assessing conflicting arguments in legal reasoning. Artif Intell Law 4:331–368

Prakken H, Sartor G (1998) Modelling reasoning with precedents in a formal dialogue game. Artif Intell Law 6:231–287

Raz J (1979) The authority of law. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Rigoni A (2014a) Common-law judicial reasoning and analogy. Leg Theory 20(02):133–156

Rigoni A (2014b) Legal rules, legal reasoning, and nonmonotonic logic. University of Michigan, Michigan

Ross A (1957) Tû-Tû. Harv Law Rev 70(5):812–825

Roth B (2003) Case-based reasoning in the law: a formal theory of reasoning by case comparison. Universiteit Maastricht, Maastricht

Schauer F (2006) Do cases make bad law? Univ Chic Law Rev 73:883–918

Schauer F (2008) Why precedent in law (and elsewhere) is not totally (or even substantially) about analogy. Perspect Psychol Sci 3(6):454–460

Schauer F (2012) Precedent. In: Marmor A (ed) Routledge companion to philosophy of law. Routledge, New York, pp 123–136

School Dist. of Abington Twp., Pa. v. Schempp 374 U.S. 203 (1963)

Shapiro SJ (2013) Legality. Belknap Press, Cambridge

Siegler A (1984) Alternative grounds in collateral estoppel. Loyola Los Angel Law Rev 17:1085–1124

Simpson AWB (1961) The ratio decidendi of a case and the doctrine of binding precedent. In: Guest AG (ed) Oxford essys in jurisprudence: a collaborative work. Oxford University Press, London, pp 148–175

Stencel Aero Engingering Corp v. U.S. 431 U.S. 666 (1977)

Terry v. Ohio 392 U.S. 1 (1968)

The Newport Yacht Basin Ass’n v. Supreme Northwest Inc. 168 Wn. App. 56 (2012)

Thielscher M (2000) The qualification problem. Challenges for action theories. Springer, Berlin, pp 85–118

Walz v. Tax Comm’n of N.Y. 397 U.S. 664 (1970)

Weiner SA (1966) The civil jury trial and the law-fact distinction law-fact distinction. Calif Law Rev 54(5):1867

White EG (1987) Earl warren: a public life. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Acknowledgments

I am greatly indebted to Richmond Thomason, Kevin Ashley, Peter Railton, and an anonymous reviewer at AI and Law for extensive written comments on earlier drafts of this article. I have also greatly benefited from discussion with Phoebe Ellsworth and Ishani Maitra.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rigoni, A. An improved factor based approach to precedential constraint. Artif Intell Law 23, 133–160 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10506-015-9166-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10506-015-9166-x