Abstract

The Continuum concept of pluralisation is often misunderstood. This paper aims to explain how records are embedded in the society that created them from the time of their creation and how they can be further embedded throughout their lifespan by adding metadata to them, placing them in context, making them accessible to those who will need them in the future and potentially sharing them with the broader society according to societal rules. The author proposes to use the concept of societal embeddedness, which indicates that pluralisation is not just about sharing in the future, but also about incorporating societal expectations in records and recordkeeping systems, to help explain the concept of pluralisation. She shows how using simple examples from everyday life and discussing the societal context of the creation and use of records can help explain Records Continuum concepts, and in particular the concept of pluralisation, to students from non-English speaking backgrounds.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In his translation of the Records Continuum Model into Dutch, Hans Hofman translated the name of the fourth dimension of the Records Continuum, “Pluralise”, as “maatschappelijk inbedden”, literally “to embed in the society” (Horsman et al. 1999, p. 147). In this paper, I will argue that the concept of societal embeddedness can be useful to explain the meaning of pluralisation. This concept has some similarities with the concept of societal provenance developed by Nesmith (2006) in Canada and Piggott (2012) in Australia, but is broader since it encompasses the context of the creation of records and their future uses.

When teaching Records Continuum concepts to foreign students, basic concepts, including the concept of record, which may have a different meaning in their language, need to be explained first. As Eric Ketelaar has written, “There are many … terms in the professional archival terminology which are only understandable in another language when one knows and fully understands the professional, cultural, legal, historical, and sometimes political background of the term” (Ketelaar 1997, p. 143). Therefore, one of the first things to do is to discuss the meaning of the words records, recordkeeping and archives and their translation in their language. Being myself from a different linguistic background, I had been confronted with the issue of trying to translate archival terminology into my first language (French) when I started studying archival science in Australia. The difficulties associated with translating some terms that do not have direct equivalent made me reflect on the meaning of the recordkeeping terminology that we use in Australia so as to find appropriate equivalent terms in French, and consequently got me interested in translation problems and in comparative archivistics (Ketelaar 2000). Many European languages do not have a word for record. This has for consequence that the English concept of records gets translated differently depending on the context. In some other languages, including Chinese, the words used by archivists are different from the words used by ordinary people, which can confuse students. To further complicate the issue, the way the words records and recordkeeping are used in Australia to encompass both records and archives, and records management and archives management are different from the ways they are used in the rest of the English-speaking world. This needs to be clarified and examples discussed with the students before discussing the Records Continuum Model.

In this paper, I reflect on how translating the model and teaching continuum concepts to foreign students help us to better understand the concepts that we use and to realise how much societal context is embedded into records, and I show how using the concept of societal embeddedness can help explain the complexities of records creation and use through time and space. I propose to use the concept of societal embeddedness to explain the processes that take place in the Pluralise dimension. Compared to pluralisation, which is often equated to sharing the records outside the confines of the organisation that produced them, societal embeddedness has the advantage of pointing attention towards the factors that link the records to their societal context and towards the processes that must be put in place to ensure that the records can be shared outside the organisation that created them and managed them. It is not meant to replace pluralisation, but to enhance our understanding of it.

The paper starts with a brief literature review on some of the misunderstandings of the Records Continuum Model and on its use as a teaching tool. Then, I present two examples that I used to teach the model to foreign students in two different contexts, in Australia and in the United Arab Emirates, and discuss the cultural adaptations that I made. In the last section, I reflect on the concept of societal embeddedness of records and on its relationships with the Continuum concepts of co-creation and pluralisation, and with the concept of societal provenance. I define the concept of societal embeddedness and argue that the concept of societal embeddedness helps to explain the meaning of pluralisation and to explain how records are both embedded in a societal context from the time of their creation and need to be further embedded in that context over time to meet the needs of all potential stakeholders.

The Records Continuum as a teaching tool

The Records Continuum Model (Upward 1996, 1997) was initially developed as a teaching tool to communicate evidence-based approaches to archives and records management (Upward 2000). It was intended to be “a tool for perceiving complexity” (Upward 2000). Its four dimensions, Create, Capture, Organise and Pluralise, provide a way of mapping recordkeeping processes that take place through time and space, encompassing the creation of documents, their capture in recordkeeping systems, their organisation into archives and their pluralisation to meet the needs of various stakeholders. The model has often been misunderstood, in particular its multidimensional essence and the meaning of the fourth dimension (Piggott, p. 192). Some critics have seen it as restricted to current recordkeeping (see, for example, Macpherson 2002, or the description of the model in the Society of American Archivists 2020 dictionary) or to records whose existence is publicly known (Karabinos 2018, 2020), while others have read it in a linear way as a tool for mapping a continuity between records and archives, while neglecting the simultaneity of recordkeeping processes (Dingwall 2010). Terry Cook wrote that the model could easily be interpreted as focusing on the first two dimensions, on the creation and capture of reliable evidence, at the expense of the fourth dimension and its focus on building and preserving societal memory, but that this was a misunderstanding of the model, not an inherent flaw (Cook 2000, pp. 8–9; Piggott 2020).

Michael Karabinos argued that the model cannot be applied if pluralisation has not taken place and that even in liberal democracies “we cannot take pluralization for granted” (2018, 2020, p. 189). As I have argued in a previous paper (Frings-Hessami 2020), his understanding of pluralisation as the process of sharing the records beyond the confines of the organisation that created them constitutes a narrow understanding of pluralisation processes, which neglects the impact of fourth dimension factors on the records and the processes that must be put in place from the time of the creation of the records to facilitate their future sharing. According to McKemmish, Upward and Reed, the Pluralise dimension is concerned with how the external environment impacts on the records and determines their nature and with “the capacity of a record to exist beyond the boundaries of creating entities, to meet the needs of those not involved with the actions precipitating record creation, capture and organization” (McKemmish et al. 2010, p. 4451). The processes that take place in the fourth dimension “enable records to be reviewed, accessed and analyzed beyond an organization or individual life, for multiple external accountability and memory purposes in and through time and space” (McKemmish et al. 2010, p. 4451).

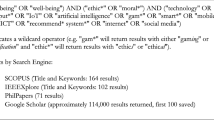

Two factors that contribute to explain why the model is often misunderstood are the fact that some of the Continuum literature is difficult to understand (Piggott 2012) and that not much has been written on teaching the model. Although the Records Continuum Model was developed as a teaching tool, the archival science literature offers very few examples of how it has been used in practice in teaching. One rare exception is a paper by Upward and McKemmish (2006), in which they discussed how they taught recordkeeping “continuum style” in a transdisciplinary environment at Monash University and included an example that they used in teaching, which had been previously published in Hartland et al. (2005). McKemmish (2005) and Reed (2005a) present examples of the application of the model, which are useful as teaching examples, but do not discuss pedagogical issues. Following their lead, I wrote a paper in which I presented an example that I used in teaching (Frings-Hessami 2018c), but the aim of that paper was to explain the model in simple terms rather than explain how I developed the example and used it as a teaching tool.

Karabinos (2020, p. 194) wrote that “Any analysis through the continuum model requires the records at least be made accessible to the person doing the analysis”. In this paper, I show that a records continuum analysis is not restricted to an a posteriori analysis of known records and that an analysis can be made a priori, before the records are created in order to set up recordkeeping systems that will enable the records to be used by multiple stakeholders for as long as they may need them.

Teaching the Records Continuum Model through an example

The best way to teach the Records Continuum Model is to explain it through an example. In particular, the use of photographs to teach the model has proved very effective. Photographs can be powerful teaching tools because they are easy to relate to, can provoke an emotive reaction, and can be meaningless without metadata. Photographs have been used to teach the Records Continuum at Monash University at least since the early 2000s, when Sue McKemmish started using a photograph from the “Children Overboard story” that made headlines in Australian media in October 2001 (McKemmish 2005). Barbara Reed’s 2005 paper, “Reading the Records Continuum: interpretations and explorations”, which takes us through a detailed explanation of several recordkeeping uses of a photograph of abuse in an offshore detention centre, is another powerful example of how a photograph can be described from different perspectives and how these perspectives can be mapped on the Records Continuum Model.

I have been teaching the Records Continuum at Monash University since 2015 and during that time we have experienced a shift in the student population enrolled in the postgraduate recordkeeping subjects taught in the Faculty of Information Technology. On the one hand, we have experienced a decline of the number of postgraduate students who enrolled in the Master of Business Information Systems with the intention of completing a specialisation in archives and recordkeeping. On the other hand, a massive increase of the number of international students enrolling in the degree has led to an exponential increase of the number of students enrolling in the two recordkeeping subjects as electives, with the assumption that they were “easy” subjects because, contrary to most other subjects in the Faculty, all assessment tasks were conducted during the semester and did not include a final examination. The combination of these factors has resulted in a shift from teaching to small classes of students (18 in the first semester of 2016), the majority of whom were intending to qualify as archivists and record managers, to very large classes of students (180 students in the first semester of 2019), most of whom had no previous understandings of records and archives and no intention of working in that area after graduating, with a very small minority of students still intent on working in records and archives. This shift in the students’ backgrounds and interests drove me to develop simpler examples to teach the Records Continuum Model.

Since 2015, I have been using the example of a family photograph (Fig. 1) to discuss the importance of metadata and possible reuses of the photograph. It started as one example among others used in tutorial group discussions, but it proved so successful, with new examples of potential reuses suggested each semester, that from the second half of 2018, it became the main example I used in a lecture to illustrate the application of the Records Continuum Model. I also used it as an example in an article I wrote in French on the Records Continuum Model for a Swiss journal (Frings-Hessami 2018c). Personal recordkeeping examples work particularly well with students with no previous experience of working in a recordkeeping role who can easily relate them to their personal experience.

The photograph in Fig. 1 is a trace of a wedding. Without any metadata, we cannot know whose wedding it was and when it took place, but from the clothes the two people in the front of the photograph are wearing, we can identify the picture as one likely to have been taken at a wedding. This photograph was taken in 1996 with an analogue camera, printed and sent to me from Belgium by the bride and the groom, whom we will call Sophie and Daniel. The first few times I used this photograph in teaching I brought the printed photograph to class to show that it did not include any metadata. No names, place or date had been written on the back of it, and it had been kept in an envelope with other photographs of the wedding rather than inserted in a photograph album. After 2 or 3 years, I lost the original and from then on, I only used the scanned copy that I had made for the lecture slides. We can safely assume that several dozens of photographs had been taken by the wedding photographer and that some of these photographs were printed several times. The new couple kept some for themselves and gave some to friends and relatives, including me. These actions took place in the Create dimension. Each copy of the photograph thenceforth followed a separate recordkeeping trail. They may have been inserted in a photograph album, put in a frame or left in the envelop they were sent in and placed in a box or in a drawer with family mementoes. Each one was captured in a recordkeeping system, however rudimentary it may have been, a photograph album, a frame on the wall or a box of mementoes. Some metadata may or may not have been added to them depending on personal habits and on how close to the couple the recipients may have been. These processes took place in the Capture dimension. Together with other pictures, photograph albums, personal documents and other mementoes, the photograph became part of the archive of each person or family and each archive was organised in a (more or less efficient) way so that the items in it could be retrieved later (Organise dimension). The photograph may also have been shared by the recipients with others either by giving them a copy or just by showing it to them (Pluralise dimension).

Having been taken in 1996, this wedding photograph was not shared on social media. However, it may have been used and reused in ways that Sophie and Daniel could not have predicted when it was taken. Over the years, students have suggested reuses such as being of interest to people who are collecting photographs about wedding fashion in the 1990s, hats or hairstyles. An original idea suggested by a student the first time I used the photograph was that of being used as an alibi for the woman in the back of the photograph. If we imagine that the woman was charged with having killed her husband on that particular day, she could have used the photograph as evidence that she was at the wedding at that time and not at the place where the murder took place kilometres away. In that case, the metadata captured with the photograph would be crucial, as well as the testimony of the photographer, to establish the veracity of her claim. If used as evidence in a criminal investigation, the photograph would be captured in a very different type of recordkeeping system, such as that of the police, together with the deposition of the accused and other records relating to the case, organised in the archive of the police department and potentially presented as evidence during the trial or shared with the media, before being transferred, according to prescribed schedules, to the archives of the jurisdiction.

Another use that nobody could have predicted in 1996 is its use in lecture slides, or in a journal article (Frings-Hessami 2018c), as an example to teach the Records Continuum Model, which involved scanning the photograph, uploading it on my laptop, inserting it the lecture slides (and later in a journal article), writing some information about its context, sharing it with students during the lectures and with the readers of the journal, and preserving it with the teaching materials for the recordkeeping course. Although a copyright sign was included in the lecture slides and on the journal’s website, it is difficult to predict what other (unauthorised) uses the photograph may be subject to after it has been shared with students and published.

Each use of the photograph can be mapped as a separate recordkeeping trail on the Records Continuum Model as shown in Fig. 2. Each one starts from the Create dimension when the photograph is created or received by someone, then is captured in different recordkeeping systems, organised for different purposes, and maybe shared with others. Every time it is shared and reused, it goes back to the Create dimension and starts a new recordkeeping trail by a different user looking at it from a different perspective and using it for a different purpose. Although representing processes that happen simultaneously as lines on a diagram can be confusing and gives a false impression of linearity, it helps to understand the different processes that take place in each case.

Reading the Records Continuum inwards

The Records Continuum Model can be read outwards, as we have done in the previous section, starting from the Create dimension at the centre of the diagram, or inwards, starting from the Pluralise dimension, the outermost circle in the diagram (Upward 2000; Reed 2005b). Reed (2005b) wrote that “Depending on individual preference, explanations will work outwards exploring the circles as ripples precipitated from an instance or action in the first dimension, or alternatively, work inwards exploring the circles as cascading regions emanating from the social and cultural dimensions represented by the outermost circle” (Reed 2005b, p. 19).

An inwards reading starts from the cultural contexts and the mandates for the creation of records in the Pluralise dimension. These mandates dictate how organisations function and the records that they must create. The sociocultural context in which people live and the technology they have access to, the laws and customs that regulate how they interact with one another and conduct their business and private affairs, all impact on the creation of records. In the case of a wedding photograph, the importance accorded to weddings in the society where the bride and groom live, which encourages people to take photographs to remember the occasion, the type of cameras at their disposal, the systems in which the photographs can be captured—physical (photograph albums, frames) or digital—and people’s access to tools to share the photographs (mail, email, social media), all impact on the creation, management and use of the photographs, while privacy laws may regulate the taking and sharing of photographs. All of these factors from the Pluralise dimension influence the processes that are taking place in the other three dimensions.

Then, in the Organise dimension, we look at how organisations and families manage their affairs and at the recordkeeping systems they set up to manage the records that they want to keep. These are impacted by societal expectations and the technology available (Pluralise dimension), as well as by the individual preferences of the members of the organisation or family (Create and Capture dimensions). The family makes decisions about the taking of photographs as part of the planning of the wedding and has previously put in place (or will set up) a system that functions as a family archive, in which the photographs will be captured.

In the Capture dimension, people are involved in capturing records in a specific recordkeeping system, which they have developed and configured according to their needs and preferences, but which is impacted by the context from the Pluralise and Capture dimensions. The wedding photographs will be captured in a photograph album used for that purpose.

In the Create dimension, the photographs are created, or co-created according to the requirements from the other three dimensions. The people involved in their creation are the photographer, the person who may have paid him/her to take the photograph and the subjects of the photographs who all have a stake in the way the photographs will be used.

This type of reading can be repeated inwards or outwards for every potential use of the photographs. It illustrates the fact that the four dimensions are always present, that “A record exists at the same time in all dimensions” (Reed 2005b, p. 21). Factors from the Pluralise dimension always impact on the ways in which records are created, managed and used even if those records are not shared outside of the organisation or the family who created them.

Teaching the Records Continuum in a different cultural context

The example of the wedding photograph shows that a lot of societal context is embedded in the photograph from the time of its creation. The clothes worn, the jewellery, the hairstyles and the setting are reflective of the society in which the wedding took place and are signs that enable observers to identify the picture as that of a wedding. In itself, the fact that the picture was taken is a reflection of the importance attached to weddings as symbolic events deemed important to capture in that society at that particular time. The fact that the photograph is taken to be shared with friends and relatives as a memory of the wedding is a reflection of societal values, customs and expectations, as well as of personal values and preferences, which together determine with whom it is acceptable to share the photograph. In some other cultural contexts, for example in traditional Muslim societies, the setting of the wedding would be very different and it would not be acceptable to share a picture of the bride. In some fundamentalist societies, the taking of photographs in itself may not be acceptable.

The realisation of how much societal context is embedded in this particular photograph led me to develop a different example, more appropriate to a Muslim context, when I prepared a guest lecture on the Records Continuum for an undergraduate course in records management taught in Abu Dhabi. I used a young boy’s photograph (Fig. 3) as more culturally appropriate than a picture of an unveiled woman. The example enabled me to discuss how the photograph could be used and shared while relating it to a context with which the students (male and female) could more easily and more comfortably identify. The discussion of the photograph of a 2-year-old boy in a playground could include a discussion of sharing the photograph with his grandparents overseas who would be happy to receive it and may capture it in a frame or photograph album, treasuring it more because of the distance, including his name and the date they received the photograph; as well as a discussion of picture frames and photograph albums as recordkeeping systems, of the importance of context, and of possible online sharing of the photograph enabling various reuses, such as the use of the picture in the lecture slides or by people with an interest in children fashion or playground equipment in Australia in the 1990s. Other cultural adaptations brought to the delivery of this (online) lecture for Middle Eastern students included introducing myself by my Muslim name, wearing hijab, and sharing family stories that had taken place in Muslim contexts.

I have previously argued that the Records Continuum Model, or variations of it such as the models I have developed (Frings-Hessami 2017, 2018a, b, 2019, 2020), or the Information Continuum Model (Frings-Hessami et al. 2020) are flexible enough to be applied in different cultural contexts to analyse how records are used and reused over time by different people for different purposes. The models enable the representation of interactions between the records and the societal context in which they are used, whatever it might be. Each society has laws, regulations, customs and expectations which impact on the way records are created, managed and used in that society. These laws, regulations, customs and expectations are represented in the Pluralise dimension of the Records Continuum Model and impact on what is happening in the other three dimensions. Records are created to meet societal expectations and are captured, managed, accessed, shared and used in ways that meet those expectations. Each record that is kept as a record will be captured in a recordkeeping system of some sort (from someone’s memory or a simple box to an electronic records management system) together with related records, and will be preserved so that it can later be retrieved and used again or shared with others. Some contextual elements are embedded in the records from the time of their creation, but additional elements will need to be embedded into them so that the records can meet the needs of all their potential users over time. This is happening in the Pluralise dimension of the Records Continuum where measures are put in place to ensure that records will remain accessible over time and will meet the needs of all the people who may need them. These measures include developing systems to preserve the records so that they will survive through time and transferring them to archival institutions for long-term preservation, as well as respecting the laws, regulations and expectations of the society in which the records are created.

Reflection on the societal embeddedness of records

The examples presented in this paper show how the Record Continuum Model can be applied in different cultural contexts and help to understand the meaning of pluralisation. I propose to use the concept of societal embeddedness to explain the processes that take place in the Pluralise dimension. I believe that the concept of societal embeddedness points attention towards the factors that link the records to their societal context and towards the processes that must be put in place to ensure that the records can be shared outside the organisation that created them and managed them. Therefore, it can enhance our understanding of pluralisation. The pluralisation processes can be happening autonomously or they may require intervention to make them happen. The records are both embedded in the societal context in which they were created from the time of their creation and need to be further embedded in that context.

The concept of societal embeddedness is related to the concept of societal provenance, but is broader as it encompasses the context of the creation of records and their future uses. Provenance has traditionally been defined as “the person, agency or office of origin that created, acquired, used and retained a body of records in the course of their work or life” (Millar 2017, p. 46). Tom Nesmith wrote that provenance also includes “the societal and intellectual contexts shaping the actions of the people and institutions who made and maintained the records, the functions the records perform, the capacities of information technologies to capture and preserve information at a given time, and the custodial history of the records” (Nesmith 2002, p. 35) and advanced the concept of societal provenance (Nesmith 2006). He suggested that “Societal provenance is not just another layer of provenance information to add to other ones such as the title of the creator(s), functions, and organizational links and structures. The societal dimension infuses all the others” (p. 352). Bastian (2003) argued that the provenance of records could be extended to the entire society that produced them. Chris Hurley wrote of the “ambience” of provenance, its broader context (1995, 2005a, b) and articulated the concepts of parallel provenance and simultaneous multiple provenance, which allow two or more creators to be identified at the same time (2005a, b). The concept of societal provenance was further extended by Piggott (2012) who used it to frame the history of recordkeeping in Australia. Whereas other studies that used the concept focused on a single document or a single archival collection, Piggott employed it to analyse larger and more varied collections with the aim to explore the relationships between the Australian society and its records (Piggott 2012, p. 4).

Explaining societal provenance, Nesmith wrote that:

Document creation, use and archiving have social origins. People make and archive records in social settings for social purposes. They do so with a concept of how their social setting works, where they fit into it, and might change it. Socio-economic conditions, social assumptions, values, ideas, and aspirations shape and are shaped by their views and recording and archiving behaviour. Social circumstances shape what information may be known, what may be recorded and what may not, and how it may be recorded, such as in the medium chosen. These circumstances affect who has information and why, and who may have access to it. They influence the language used to describe phenomena. They shape what is deemed trustworthy, authentic, reliable, worth remembering or forgettable, and how and when this information is used, and by whom (Nesmith 2006, p. 352).

This is very close to McKemmish, Upward and Reed’s description of the fourth dimension as “the cultural, legal, and regulatory environment of recordkeeping, which is different for every society and in every period” (2010, p. 4451), and to the way I described the processes that take place in the Pluralise dimension in the examples of the two photographs.

In the entry for the principle of provenance in the “Encyclopedia of archival science”, Nesmith wrote that:

provenance is an ongoing process in which records are created and re-created, arising from knowledge of the history of the records as shaped by … various formative influences… from initial inscription to acquisition and use in archives, perhaps centuries later (Nesmith 2015, p. 287).

This notion of ongoing creations and re-creations through time reflects an understanding of records similar to that of a continuum perspective, of records “always in a process of becoming” (McKemmish 1994), while Nesmith’s previously cited quote that the societal dimension “infuses all the others” suggests an understanding of societal provenance as one dimension which exists in parallel with and is interconnected with others as the four dimensions of the Records Continuum are. Nesmith himself saw some similarities between his expanded understanding of provenance and Australian ideas and practices, including the continuum, the concept of parallel provenance, and the Australian Series System, which “suggest that records are the product of a variety of factors acting across their entire history” (2006, p. 352).

Conversely, McKemmish wrote that the Australian series system “provides a fourth dimension framework for carrying records beyond the life of an individual or organisation by enabling the representation of the broader structural, functional, and documentary contexts of their creation, management, and use” (McKemmish 2001, p. 351). The concepts of parallel provenance and multiple simultaneous provenance are associated with the concept of co-creation, which recognises as co-creators “all those who participate in or are directly impacted by the events or actions” documented in a record (McKemmish 2017, p. 147). Multiple simultaneous provenance, parallel provenance and co-creation have been adopted by continuum thinkers (e.g. McKemmish 2017) and included in the Re-imagined Records Continuum Model developed by Sue McKemmish (Evans et al. 2017).

The need to take into account the broader context and multiple provenance of records creation and to acknowledge records’ co-creators has been discussed in the archival literature in recent years (Gilliland and McKemmish 2014; Evans et al. 2015, 2019). However, the concept of societal provenance has been rarely used by continuum researchers or by the broader archival research community. None of the 34 papers in the Research in the Archival Multiverse (Gilliland et al. 2017) massive compilation uses it. Two rare exceptions in Australia, both from practitioners, are Piggott’s Archives and Societal Provenance (2012) and a recently published paper in which Anne-Marie Condé applies the concept to the analysis of World War I service records (Condé 2020).

The concept of societal provenance has many similarities with records continuum theory, and it could help to explain both the concepts of co-creation and pluralisation. Although societal provenance has been used mostly in relation to the history of records included in archival collections, I believe that it could be extended to analyse the societal context of the creation of new records and their future uses. However, in order to avoid creating further confusion, following the lead of Hofman’s translation, I propose to use the concept of societal embeddedness, which has the advantage of suggesting the possibility of future actions to be taken by those who create and manage records to make the records accessible to the broader community. The records are both embedded in the society that created them from the time of their creation and need to be further embedded so that they can be used by multiple stakeholders.

The wedding photograph from Fig. 1 incorporates intrinsic elements that link it to its context. Its format is the product of the technology used to produce it. Its content is impacted by the societal context in which it was taken and the socio-economic status of the people who figure in it (and their religion in the case of a cultural event like a wedding). The fact that it exists is, in itself, a reflection of the value accorded to weddings in the society, the technology in existence and its affordability. The picture may have been kept for memory purposes (as a souvenir of an important event) or as evidence (as in the case of the woman potentially charged with homicide). In order to be kept as memory or as evidence of the wedding, it needs to be captured and organised in a recordkeeping system and metadata added to it. If it is to be shared beyond the immediate circle of family and friends, additional metadata will need to be added to it to place it in its societal context, to embed it in that context, in a way that will make sense to others. Similarly, in the case of the young boy’s photograph (Fig. 3), contextual elements are embedded in the photograph from the time of its creation, other elements need to be embedded before the photograph can make sense to others and steps need to be taken to preserve the photograph. The processes that will ensure that both photographs will be preserved are dependent on the technology available, the legislation in place and the cultural expectations, and they require an active involvement in order to ensure that the photograph will be preserved for as long as it may be needed. This may involve keeping the photograph and its metadata in a stable system and transferring it to another system if/when necessary. The fact that some societal aspects are embedded into the records from the beginning while others need to be explicitly added over time illustrates how pluralisation occurs at the same time as the other dimensions.

Conclusion

Teaching to foreign students forces us to reflect on how to adjust our teaching practices to explain to people from other cultural and linguistic backgrounds recordkeeping concepts that may not have a direct equivalent in their languages and to develop examples that are culturally appropriate. The experience of translating the model into French (Frings-Hessami 2018c) made me conscious of the translation issues experienced by students from non-English speaking background, and made me reflect on the meaning of the recordkeeping terminology that we use in Australia. Later on, reading an explanation of the model in Dutch and seeing how some of the terms had been translated into Dutch, made me reflect further on the meaning of some terms and on possible alternative terminology to explain the concepts in English, in particular the concept of pluralisation. By proposing to use the concept of societal embeddedness to explain the concept of pluralisation, I hope to clarify the meaning of the fourth dimension of the Records Continuum Model and to show that outside factors impact on the creation, management and use of records, and, beyond that, to encourage students, as well as archival researchers and practitioners, to reflect on the societal contexts of records and on how they can change their practice to better meet societal needs. The examples that I use in this paper also show that a Records Continuum analysis is not restricted to an a posteriori analysis of known records. A Records Continuum analysis can also be made a priori, before the records are created, or at any time during their lifespan, in order to inform the development of recordkeeping systems that will enable the records to be used by multiple stakeholders for as long as they need them. This is what I hope my students will remember from their course whether they work as recordkeepers, as business analysists or as IT professionals and, hopefully, they will go and design systems that will make it possible to preserve records for evidence and memory purposes that meet the needs of all present and future stakeholders.

References

Bastian J (2003) Owning memory: how a Caribbean community lost its archives and found its history. Libraries Unlimited, Westport

Condé AM (2020) A societal provenance analysis of the First World War service records held at the National Archives of Australia. Arch Manuscr 48(2):142–156

Cook T (2000) Beyond the screen: the records continuum and archival cultural heritage. Paper presented at the Australian Society of Archivists conference, Melbourne, 18 Aug 2000

Dingwall G (2010) Life cycle and continuum: a view of recordkeeping models from the postwar era. In: Eastwood T, MacNeill H (eds) Currents of archival thinking. Libraries Unlimited, Santa Barbara, pp 139–161

Evans J, McKemmish S, Daniels E, McCarthy G (2015) Self-determination and archival autonomy: advocating activism. Arch Sci 15(4):337–368

Evans J, McKemmish S, Rolan G (2017) Critical approaches to archiving and recordkeeping in the continuum. J Crit Stud 1(2). https://doi.org/10.24242/jclis.v1i2.35. Accessed 4 May 2020

Evans J, McKemmish S, Rolan G (2019) Participatory information governance: transforming recordkeeping for childhood out-of-home care. Rec Manag J 29(1–2):178–193

Frings-Hessami V (2017) Looking at the Khmer Rouge archives through the lens of the records continuum model: towards an appropriated archive continuum model. Inf Res 22(4). http://www.informationr.net/ir/22-4/paper771.html. Accessed 16 July 2020

Frings-Hessami V (2018a) Care Leaver’s records: a case for a repurposed archive continuum model. Arch Manuscr 46(2):158–173

Frings-Hessami V (2018b) Indigenous archives through time and space: towards a continuum model to explain the complex contexts of indigenous archives. Archifacts 2018(2):52–62

Frings-Hessami V (2018c) La perspective du continuum des archives illustrée par l’exemple d’un document personnel [The perspective of the records continuum illustrated by the example of a personnel record]. Rev Electr Suisse Sci Inf 19. http://www.ressi.ch/num19/article_149. Accessed 16 July 2020

Frings-Hessami V (2019) Khmer Rouge archives: appropriation, reconstruction, neo-colonial exploitation and their implications for the reuse of the records. Arch Sci 19(3):255–279

Frings-Hessami V (2020) The flexibility of the records continuum model: a response to Michael Karabinos’ ‘In the shadow of the continuum. Arch Sci 20(1):51–64

Frings-Hessami V, Sarker A, Oliver G, Anwar M (2020) Documentation in a community informatics project: the creation and sharing of information by women in Bangladesh. J Doc 76(2):552–570

Gilliland AJ, McKemmish S (2014) The role of participatory archives in furthering human rights, reconciliation and recovery. Atlanti 24(1):78–88

Gilliland AJ, McKemmish S, Lau AJ (eds) (2017) Research in the archival multiverse. Monash University Press, Clayton

Hartland R, McKemmish S, Upward F (2005) Documents. In: McKemmish S, Piggott M, Reed B, Upward F (eds) Archives: recordkeeping in society. Centre for Information Studies, Charles Sturt University, Wagga Wagga, pp 75–100

Horsman PJ, Ketelaar FCJ, Thomassen THPM (1999) Hoofdstuk 3: The professie [Chapter 3: The profession]. In: Horsman PJ, Ketelaar FCJ, Thomassen THPM (eds) Naar een nieuw paradigma in de archivistiek. Jaarboek 1999 [Towards a new paragdim in archivistics. 1999 Yearbook]. Stichting Archiefpublicaties,’s-Gravenhage, pp 145–150. https://kvan.courant.nu/periodicals/JB/1999. Accessed 28 Apr 2020

Hurley C (1995) Ambient functions: abandoned children to zoos. Archivaria 40:21–39

Hurley C (2005a) Parallel provenance part 1: what if anything is archival description? Arch Manuscr 33(1):110–145

Hurley C (2005b) Parallel provenance part 2: when something is not related to everything else. Arch Manuscr 33(2):52–91

Karabinos M (2018) In the shadows of the continuum: testing the records continuum model through the Foreign and Commonwealth Office ‘Migrated Archives’. Arch Sci 18(3):207–224

Karabinos M (2020) Acknowledging the shadows. Arch Sci 20(2):187–196

Ketelaar E (1997) The difference best postponed? Cultures and comparative archival science. Archivaria 44:142–148

Ketelaar E (2000) Archivistics research saving the profession. Am Arch 63:322–340

Macpherson P (2002) Theory, standards and implicit assumptions: public access to post-current government records. Arch Manuscr 30(1):6–17

McKemmish S (1994) Are records ever actual? In: McKemmish S, Piggott M (eds) The records continuum: Ian Maclean and Australian Archives first 50 years. Ancora Press, Clayton, p 1994

McKemmish S (2001) Placing records continuum theory and practice. Arch Sci 1(4):333–359

McKemmish S (2005) Traces: document, record, archive, archives. In: McKemmish S, Piggott M, Reed B, Upward F (eds) Archives: recordkeeping in society. Centre for Information Studies, Charles Sturt University, Wagga Wagga, pp 1–20

McKemmish S (2017) Recordkeeping in the continuum: an Australian tradition. In: Gilliland AJ, McKemmish S, Lau AJ (eds) Research in the archival multiverse. Monash University Publishing, Clayton, pp 122–160

McKemmish S, Upward FH, Reed B (2010) Records continuum model. In: Bates MJ, Niles-Maack M (eds) Encyclopedia of library and information sciences, 3rd edn. Taylor & Francis, New York, pp 4447–4459

Millar L (2017) Archives principles and practices, 2nd edn. Facet Publishing, London

Nesmith T (2002) Seeing archives: postmodernism and the changing intellectual place of archives. Am Arch 65(1):24–41

Nesmith T (2006) The concept of societal provenance and records of nineteenth century Aboriginal-European relations in Western Canada: implications for archival theory and practice. Arch Sci 6:351–360

Nesmith T (2015) The principle of provenance. In: Duranti L, Franks P (eds) Encyclopedia of archival science. Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham, pp 284–288

Piggott M (2012) Archives and societal provenance: Australian essays. Chandos Publishing, Oxford

Piggott M (2020) Community archives and the records continuum. In: Bastian J, Flinn A (eds) Community archives, community spaces: heritage, memory and identity. Facet, London, pp 41–59

Reed B (2005a) Beyond perceived boundaries: imagining the potential of pluralised recordkeeping. Arch Manuscr 33(1):176–198

Reed B (2005b) Reading the records continuum: interpretations and explorations. Arch Manuscr 33(1):18–43

Society of American Archivists (2020) Records continuum. Dictionary of archives terminology. https://dictionary.archivists.org/entry/records-continuum.html. Accessed 25 May 2020

Upward F (1996) Structuring the records continuum part one: post custodial principles and properties. Arch Manuscr 24(2):268–285

Upward F (1997) Structuring the records continuum part two: structuration theory and recordkeeping. Arch Manuscr 25(1):10–35

Upward F (2000) Modelling the continuum as paradigm shift in recordkeeping and archiving processes, and beyond—a personal reflection. Rec Manag J 10(3):115–139

Upward F, McKemmish S (2006) Teaching recordkeeping and archiving continuum style. Arch Sci 6(2):219–230

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Frings-Hessami, V. The societal embeddedness of records: teaching the meaning of the fourth dimension of the Records Continuum Model in different cultural contexts. Arch Sci 21, 139–154 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-020-09349-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-020-09349-6