Abstract

Probability density functions of the components of stretch rate are investigated using a previously-published Direct Numerical Simulation dataset spanning a range of turbulence intensities in the Thin Reaction Zones (TRZ) regime. The dataset was generated by varying the turbulence intensity across five different simulations while maintaining fixed the remaining physico-chemical input parameters such as integral length scale and laminar flame thickness and speed. Across the entire dataset, the joint probability density function of stretch rate and displacement speed displays a distinctive shape with two branches consistent with previous studies at low turbulence intensities. This joint probability density function is analysed further by extracting individual contributions of stretch rate components to determine their relative importance across the branches. The curvature dependence of displacement speed appears to play an important role in shaping these branches. Implications of this result with regard to evaluation of the components of stretch rate in the TRZ regime are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

1.1 Flamelet modelling: stretch rate and the displacement speed

In flamelet modelling of turbulent premixed flames, the rate at which reactants are transformed into products is a function of the mean stretch rate \(\langle \dot {s} \rangle \) of the flame surface [1]. The instantaneous stretch rate \(\dot {s}\) of the flame surface is defined as the fractional rate of change of its area A [2] as follows

with the flame surface itself represented by an isosurface of the reaction progress variable c which is defined as

where Y is the local mass fraction of a suitable reacting species, the subscripts R and P denoting its value in the reactant and product mixtures, respectively. At any point on a progress variable isosurface c = c∗, the local instantaneous stretch rate \(\dot {s}\) is written as [3, 4] a linear combination

of its components at and sdhm that represent individually:

-

1.

the tangential strain rateat imposed by the flow field u on the local tangent plane to the flame surface as given by

$$ a_{t} = {\nabla} \cdot \boldsymbol{u} - \boldsymbol{n} \boldsymbol{n}:{\nabla} \boldsymbol{u}, $$(4)where n ≡−∇c/|∇c| is the local unit normal vector defined to be positive in the direction of the reactant mixture, ∇ is the gradient operator and |⋅| is the Euclidean norm, and

-

2.

the propagation ratesdhm of the flame surface which operates in regions of non-zero mean curvature

$$ h_{m} \equiv - (1/2) {\nabla} \cdot \boldsymbol{n}, $$(5)by virtue of its local displacement speed

$$ s_{d} = {\left[\frac{ \dot \omega + \nabla \cdot \left( \rho {D} \nabla c \right)} { \rho |\nabla c| } \right]}_{c^{*}}, $$(6)where \(\dot {\omega }\) is the reaction rate, ρ is the local mixture density and D is the molecular diffusivity of the same chemical species that defines the progress variable c.

Given that the mean stretch rate \(\langle \dot {s} \rangle \) governs the overall transformation rate of reactants as mentioned at the outset, the key task of flamelet modelling is the estimation of \(\langle \dot {s} \rangle \) using approximations for the individual stretch-rate components at, hm, and sd. These components, however, are strongly coupled and the underlying inter-dependences are highly non-linear. For example, instantaneous as well as persistent strain at can affect both displacement speed sd [5] and flame curvature hm [6]. In turn, the flame curvature has a strong influence on the displacement speed [7, 8]. Subsequently, the resulting displacement speed may enhance or inhibit the flame curvature further [9]. Finally, the propagation of the flame surface changes the strain field experienced by it [10]. These effects highlight the recursive nature of the relationship between instantaneous stretch rate \(\dot {s}\) and its components, particularly that between \(\dot {s}\) and sd. This renders flamelet modelling and the associated task of estimating the mean stretch rate \(\langle \dot {s} \rangle \) challenging.

In order to simplify the estimation procedure for \(\langle \dot {s} \rangle \), the expected dependences between \(\dot {s}\) and its components are usually delineated into regimes. These regimes are based on the ratio u′/sL of turbulence intensity u′ and the unstrained laminar flame speed sL, and the ratio ℓ0/δL of integral length scale ℓ0 and the unstrained laminar flame thickness δL [2]. In the low turbulence intensity regime where u′/sL ∼ 1, approximate expressions have been developed for sd as a function of the stretch rate \(\dot {s}\) [11]. However, such expressions are generally not applicable to higher intensity regimes where u′/sL ≫ 1 [12]. Consequently, the question remains: what relationships hold between the stretch rate components for increasing values of u′/sL?

1.2 Thin reaction zones regime: scope of present work

In recent years, Direct Numerical Simulation (DNS) has provided evidence of correlations between stretch rate components for moderate- and high-intensity turbulence [13,14,15,16]. In these investigations, the Karlovitz number, a dimensional group defined as

based on the two ratios mentioned above, has been used for delineating the various possible relationships between \(\dot {s}\) and its components. The regime addressed by these recent simulations, known as the Thin Reaction Zones (TRZ) regime, corresponds to a Karlovitz number 1 < Ka < 100. In this regime, the dependence of displacement speed sd on curvature hm has been observed to be significant towards estimation of the overall stretch rate [13, 15]. Furthermore, the effects of hm on sd have been found to be regulated by the Lewis number Le, the ratio of the thermal diffusivity to the molecular diffusivity of the reacting mixture [17]. In multi-species mixtures, these effects may be exaggerated due to differential diffusion [18]. As a result, the overall relationship between sd and \(\dot {s}\) in the TRZ regime is necessarily complicated and differs significantly from the expressions [19] derived for low-intensity regimes.

In this context, a relatively early 2D DNS study of methane-air combustion with detailed chemistry [9] has elaborated upon a distinctive branched shape of the distribution between \(\dot {s}\) and sd in the low to moderate intensity region of the TRZ regime. This shape was also seen, but not discussed, in a more recent 3D DNS study with single-step chemistry at similar turbulence intensities [20]. Most recently, the branched shape has also been observed in 3D DNS of planar turbulent methane-air flames using detailed chemistry at moderate turbulence intensities [21]. The shape of this distribution has implications with regard to estimation of the propagation term in the mean stretch rate \(\langle \dot {s} \rangle \). However, since these simulations have considered a relatively narrow range of Ka values, it remains to be confirmed if the branched distribution holds for a broader range of u′/sL values for a given value of ℓ0/δL. If it holds, then what factors determine such a branched shape? The present study takes up these open questions, the objective being to discern the relationship between stretch rate components as observed for increasing values of u′/sL in the TRZ regime. Correlations between stretch rate components are investigated within a 3D DNS dataset [22, 23] generated by varying u′ systematically from 1.5sL ≤ u′≤ 30sL to span vertically the entire TRZ regime (1 < Ka < 100) by maintaining fixed the ratio ℓ0/δL as shown in Fig. 1.

In the following section, the DNS dataset investigated here is described briefly. In Section 3, stretch rate component correlations are examined, and these correlations are discussed in the context of modelling in Section 4.1.

2 Direct Numerical Simulation Dataset

The dataset investigated here consists of five separate DNS cases obtained by solving the Navier-Stokes equations in 3D compressible form along with equations for the transport of a reacting species. In each simulation, homogeneous isotropic turbulence of desired intensity is initialized in an inflow-outflow configuration. An identical copy of the turbulent flow field is convected through the inlet at a mean axial velocity equal in magnitude to the unstrained laminar flame speed so as to maintain the turbulence ahead of the flame. A statistically-planar flame brush is allowed to propagate freely towards the inlet. At any given snapshot in time, the instantaneous flame brush defined as the spatial region corresponding to 0.05 < c < 0.95 remains far from the inlet and outlet boundaries.

Flame chemistry is represented using a single-step Arrhenius reaction mechanism with the Lewis number of the reacting species set equal to unity. The laminar flame speed sL = 0.39ms− 1 is computed as the consumption speed of an unstrained 1D laminar premixed flame, and is intended to be representative of stoichiometric methane-air combustion. Similarly, the laminar flame thickness δL = 0.36mm based on the maximum temperature gradient for the unstrained 1D laminar premixed flame. Further details are provided in the references [22, 23].

The key feature of the dataset is that all parameters pertaining to the flame thermo-chemistry are maintained fixed as well as maintaining fixed turbulent flow parameters such as the integral length scale while varying only the turbulence intensity u′. The value of u′ at the inlet ranges from as low as 1.5sL to as high as 30sL as reported in Table 1. The turbulence decays in intensity slightly from the inlet up to the leading edge of the flame brush. The turbulence intensity u′|le/sL computed at the leading edge is presented alongside in Table 1. In accordance with earlier work [22, 23], it is the inlet turbulence intensity u′ that is employed throughout the analysis and presentation of results. The integral length scale ℓ0 remains nearly constant from the inlet up to the leading edge of the flame brush. The values for the integral length scale ℓ0 and the Taylor length scale λ computed for the (initial) Batchelor-Townsend energy spectrum are reported in Table 1 [22, 23]. The Karlovitz number Ka defined according to Eq. 7 based on the parameters u′ and ℓ0 varies across the dataset as shown in Fig. 1.

3 Results

All five simulations of the dataset [22] are analysed in the current work, but only three cases representative of the key trends are presented. These three cases correspond to low (1.5sL), moderate (10sL), and high (30sL) levels of u′, respectively. The cases are each run for a time t = 4τ0 eddy turn over times corresponding to each u′ level. At this point, the turbulent burning velocity sT reaches a statistically-stationary value [22, 23]. The eddy turnover time τ0 and the Damköhler number Da = τ0/τc are reported in Table 1. All statistics presented have been examined at this instant of time over the progress variable isosurface c∗ = 0.8, which is close to the peak reaction rate isosurface in the corresponding unstrained 1D laminar flame. The statistics have been extracted by first finding the locations corresponding to the c = c∗ contour by Lagrangian interpolation followed by the interpolation of required quantities to the locations found on the contour. Choice of the instant of time as well as the progress variable isosurface in the neighbourhood t ∈ (3τ0,4τ0) and c∗∈ (0.6,0.9) has little influence on the statistics obtained. The particular instant of time and progress variable serve as a representative choice for the relevant statistics captured by the dataset.

3.1 Stretch rate components

In Fig. 2, the joint probability density functions (PDFs) of stretch rate components: at, sd and hm sampled on the c∗ = 0.8 progress variable isosurface are shown for the three representative cases (u′ increases from left to right columns). The components have been normalized as in previous studies: strain rate at is normalized using the Taylor scale strain rate [24], mean curvature hm using the laminar flame thickness δL, the overall stretch rate \(\dot {s}\) is scaled based on the chemical time scale δL/sL [9], and the displacement speed is weighted by the local mixture density as \(s^{*}_{d} = \rho s_{d}/\rho _{R}\) (where ρR is the density of the unburned reactant mixture) and normalized by the laminar flame speed sL [7].

Joint PDFs of stretch rate components: strain rate, curvature and displacement speed for \(u^{\prime } = 1.5s_{L}\) (left column), \(u^{\prime } = 10s_{L}\) (centre column), and \(u^{\prime } = 30s_{L}\) (right column). Horizontal and vertical lines show the mean values. The symbol χ denotes the correlation coefficient

The joint PDF of at and hm in Fig. 2a shows that the majority of points (dark concentrated regions) correspond to zero mean curvature hm ≈ 0 (horizontal line) and an extensive strain rate at > 0 (vertical line). This conforms with the long-established picture of statistically-planar turbulent flames [24]. The correlation between at and hm is negative for all u′ values examined (left to right in Fig. 2a). The correlation coefficient χ, defined as the covariance of the two quantities normalized by the product of their individual standard deviations, denotes the strength of the correlation. The value of χ is high at low u′ levels (left panel in Fig. 2a), similar to previous studies [7, 14], and low at high u′ levels. In conclusion, the correlation strength diminishes as u′ increases (panels to the right in Fig. 2a).

The joint PDF of at and \(s^{*}_{d}\) for the low u′ case in Fig. 2b shows a positive correlation: \(s^{*}_{d}\) tends to be high in regions of extensive tangential strain rate at > 0, whereas \(s^{*}_{d}\) is low under compressive strain at < 0. The correlation strength diminishes for successively higher u′ values (panels to the right in Fig. 2b). In the highest u′ case (right panel in Fig. 2b), negative displacement speeds are noticeable (points below the horizontal line). The majority of points correspond to near-unity displacement speeds \(s^{*}_{d}/s_{L}\) (horizontal line in all panels of Fig. 2b).

The joint PDF of hm and \(s^{*}_{d}\) in Fig. 2c shows a negative correlation. High displacement speeds (\(s^{*}_{d} > s_{L}\)) are found exclusively in negatively curved regions (hm < 0), whereas low (or negative) displacement speeds (\(s^{*}_{d} \leq 0\)) are found in positively curved regions of the flame. The correlation strength does not diminish significantly with increasing intensities in contrast to the distributions involving at (Fig. 2a and b). Moreover, on close examination, it is seen that the joint PDF of hm and \(s^{*}_{d}\) has two branches (with slightly different negative slopes) that originate close to hm ≈ 0 with \(s^{*}_{d} \approx s_{L}\). A similar distribution was computed previously for a lean methane-air flame at u′ = 10sL modelled using a detailed chemical-kinetic model [9]. The present result shows that this branched distribution is maintained at higher levels of u′ (left to right panels in Fig. 2c). Furthermore, it suggests that the distribution is maintained even for single-step chemistry flames.

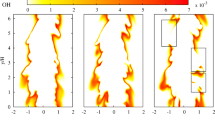

3.2 Stretch rate and displacement speed

The joint PDF of normalized stretch rate \(\dot {s} \delta _{L}/s_{L}\) and displacement speed \(s_{d}^{*}/s_{L}\) is shown in Fig. 3 for the same three cases with low, moderate, and high turbulence intensities. In all three cases, the majority of the points correspond to a region with low positive stretch \(\dot {s}\). The overall shape of the distribution does not change between the three cases: a boomerang shape with two distinct branches is observed. A similar branched distribution was also observed in 2D [9] and 3D [21] DNS of planar methane-air flames using detailed chemistry, and across a range of flame kernel sizes in 3D DNS of spherically-propagating flames [20].

In the upper branch, \(s^{*}_{d}\) is negatively correlated with \(\dot {s}\) (all panels in Fig. 3). The values of \(s^{*}_{d}\) in this branch are high and positive. The lower branch shows a positive correlation, with relatively-lower values of \(s^{*}_{d}\) and \(\dot {s}\). In the low intensity case (left panel in Fig. 3), most of the distribution belongs to this branch, supporting the use of a linear relation sd and \(\dot {s}\) as consistent with relevant theory [19]. The magnitude of \(\dot {s}\) in the lower branch increases with u′ (left to right panels Fig. 3). The stretch rate \(\dot {s}\) peaks at a low positive value in each case that increases with u′. This peak value, however, remains much smaller in magnitude than the negative stretch values attained. As noted previously for both single-step chemistry [20] and detailed chemistry flames [9, 21], the occurrence of high negative stretch rates is rare through the range of u′/sL values considered.

The joint PDF of \(\dot {s}\) and \(s^{*}_{d}\) (shown in Fig. 3) is examined further in Fig. 4 by colouring the distribution based on strain rate at and mean curvature hm. In all three cases, the upper branch corresponds to negative curvature hm < 0 and positive strain rate at > 0 (red squares in Fig. 4). The lower branch corresponds instead to regions with positive curvature hm > 0 (blue and yellow squares in Fig. 4). In the low intensity case (left panel in Fig. 4), the lower branch predominantly is characterised with compressive strain rate at < 0 (yellow squares). In higher intensity cases, positive strain rate at > 0 dominates regions with low stretch (blue squares) and negative strain rate at > 0 dominates regions with relatively higher stretch (yellow squares). The fourth configuration, negative curvature and compressive strain rate, has the least frequent contribution to the entire distribution. The shift in contributions from different regions of the flame surface points to the underlying competition between strain and curvature in determining the overall mean stretch rate \(\langle \dot {s} \rangle \) of the flame surface (here, the averaging 〈⋅〉 implies a surface mean).

The overall distribution in any of the cases may be interpreted by following the distribution curve from its upper left corner downwards towards the lower branch. The upper left corner of the distribution corresponds to negative curvature regions hm < 0 where \(s^{*}_{d}\) takes on large positive values and the stretch rate \(\dot {s}\) is high but negative. As \(\dot {s}\) decreases in magnitude along the upper branch, the normalized displacement speed \(s^{*}_{d}/s_{L}\) tends to unity. When \(\dot {s}\) is close to zero and \(s^{*}_{d}/s_{L}\) is near unity (lower right corner), the contributions from positive curvature hm > 0 begin to gain prominence. As stretch rate \(\dot {s}\) increases further along the lower branch, hm > 0 and \(s^{*}_{d} > 0\) so that propagation rate sdhm alone cannot account for the increasingly negative stretch rate values. This indicates that compressive strain rate is becoming important.

3.3 Displacement speed components

The local instantaneous displacement speed sd can be decomposed into separate components [25] as follows

which can be expressed as sd = sr + sn + st in terms of the reaction sr, normal (diffusion) sn and tangential (curvature) st components. In the following, each of these components sr, n, t have been weighted by the local mixture density (\(s^{*}_{i} = \rho s_{i}/\rho _{R}\) for i = {r, n, t} where ρR is the density of the unburned reactant mixture) and normalized using the unstrained laminar flame speed sL.

The profiles of the different \(s^{*}_{d}\) components across the instantaneous flame brush (the region corresponding to 0.05 < c < 0.95) are presented in Fig. 5a alongside the corresponding laminar case. In the laminar case (first panel in Fig. 5a), the reaction component \(s^{*}_{r}\) (blue line) is non-zero downstream of the preheat zone 0.6 < c < 0.95 where heat release occurs. The normal diffusion component \(s^{*}_{n}\) (green line) is positive in the preheat zone 0.05 < c < 0.6 and negative in the reaction zone 0.6 < c < 0.95. The tangential component \(s^{*}_{t}\) (red line) remains zero throughout.

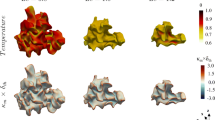

Top row: profiles of density-weighted displacement speed components \(s_{r}^{*}\), \(s_{n}^{*}\) and \(s_{t}^{*}\) in an unstrained laminar flame (left) compared with the successively increasing \(u^{\prime }\) cases (left: u′ = 1.5sL, centre: \(u^{\prime } = 10 s_{L}\), and right: \(u^{\prime } = 30 s_{L}\)). Bottom row: grouped contribution of the tangential \(s_{t}^{*}\) and reaction-diffusion \(s_{r}^{*} + s^{*}_{n}\) components in a laminar flame (left) compared with the flame subject to identical levels of turbulence intensity as above

In the turbulent cases presented alongside, the range of the curvature component \(s^{*}_{t}\) is widened (red squares in the second panel onwards to the right in Fig. 5a) as compared to the laminar case (first panel in Fig. 5a). The range of \(s^{*}_{t}\), however, remains within a band of fairly constant width across most of the instantaneous flame brush, indicating that isosurfaces of progress variable remain parallel to each other in this region. The width of this band increases with u′, particularly near the leading edge 0.05 < c < 0.2. In the low-intensity case (second panel in Fig. 5a) the curvature component \(s_{t}^{*}/s_{L}\) at any progress variable value ranges between slightly negative to unity, the majority exhibiting a negative value, especially towards the trailing edge 0.8 < c < 0.95. The \(s^{*}_{t}\) distribution tends to favour negative values as the turbulence intensity u′ is increased (second and last panel in Fig. 5a).

The normal diffusion component \(s^{*}_{n}\) stays close to the laminar profile in the low intensity case (green squares in the second panel in Fig. 5a), with a minor spread near the leading edge. The spread near the leading edge 0.05 < c < 0.2 increases as u′ is increased (green squares from second panel to last panel). In the highest intensity case, the normal diffusion component \(s^{*}_{n}\) takes up negative values. Near the trailing edge 0.8 < c < 0.95, however, the values of \(s^{*}_{n}\) exhibit a relatively-narrow distribution throughout the dataset. The reaction component \(s^{*}_{r}\) remains positive and stays close to the laminar profile for all three cases (blue squares from the second panel to the last panel in Fig. 5a).

The normal and reaction components taken together \(s^{*}_{r} + s^{*}_{n}\) are compared with the contribution of the curvature component \(s^{*}_{t}\) in Fig. 5b. In the low intensity case (second panel), reaction and normal components (blue squares) constitute together nearly the entire displacement speed. The sum \(s^{*}_{r} + s^{*}_{n}\) tends to be close to unity, i.e. \(s^{*}_{r} + s^{*}_{n} \sim s_{L}\) in line with the argument of Peters [26] for the TRZ regime. With increasing turbulence intensity (second panel to the last panel), the curvature component \(s_{t}^{*}\) contributes increasingly to the overall displacement speed supporting the inferences of 2D DNS conducted more recently [13]. In the highest intensity cases (right panels in Fig. 5a), the sum \((s^{*}_{r} + s^{*}_{n})/s_{L}\) tends to be less than unity. This is true especially near the leading edge, highlighting the role of negative diffusion component \(s^{*}_{n}\) values in this region of the instantaneous turbulent flame brush, i.e. the space corresponding to 0.01 < c < 0.99.

3.4 Strain rate and curvature response of displacement speed components

The components of displacement speed analysed above are further examined for their dependence on strain and curvature in Figs. 6 and 7, respectively.

Figure 6 shows the joint PDF between the the local strain rate at and the components of displacement speed grouped as a) \(s^{*}_{r} + s^{*}_{n}\) and b) \(s^{*}_{t}\). First, the terms at and \(s^{*}_{r} + s^{*}_{n}\) (Fig. 6a) appear to be negatively correlated, especially at low intensities (left panel in Fig. 6a), with a diminished correlation strength at higher turbulence intensities (panels to the right in Fig. 6a). This means that the contribution to displacement speed \(s^{*}_{d}\) from the normal and reaction components taken together \(s^{*}_{r} + s^{*}_{n}\) reduces as an extensive strain rate is experienced by the flame surface. For compressive straining at < 0, this contribution can be several times the unstrained laminar flame speed sL. The dependence of the tangential component \(s^{*}_{t} = -2 D h_{m}\) on strain rate at is shown in Fig. 6b. As expected, this distribution follows (with a negative sign) the dependence between curvature hm and strain rate at as noted in Fig. 2a. Interestingly, however, Fig. 6b reveals another aspect this joint probability distribution which is the increasing tendency of \(s^{*}_{t}\) (i.e. hm in Fig. 2a) to attain near-zero values over a range of extensional strain at > 0 as u′ is increased (panels from left to right in Fig. 6b).

Figure 7 shows the joint PDF of the local mean curvature hm and the components of displacement speed grouped as a) \(s^{*}_{r} + s^{*}_{n}\) and b) \(s^{*}_{t}\). First, the joint probability distribution of \(s^{*}_{r} + s^{*}_{n}\) and hm (Fig. 7a) shows a definite positive correlation, with high probabilities of near-zero positive curvatures where the contribution of \(s^{*}_{r} + s^{*}_{n}\) tends to be of the order of sL. At higher intensities (panels to the right in Fig. 7a) the dependence is not so straightforward even though signatures of positive correlation are evident. The dependence of the tangential component \(s^{*}_{t} = -2 D h_{m}\) on curvature hm is shown for sake of completeness in Fig. 7b. A deterministic linear behaviour with a negative slope is recovered as expected. Together, these joint PDFs as shown in Figs. 6 and 7 highlight the relatively complex and varied dependence of the components of \(s^{*}_{d}\) on the remaining components – at and hm – of the local stretch rate.

4 Discussion

4.1 Profiles of stretch rate components

The results above suggest that the non-linear contribution of displacement speed sd to the stretch rate \(\dot {s}\) is significant. Analysis of sd components suggests further that the curvature component st contributes primarily to this non-linearity. Using the expression for \(s^{*}_{d}\) in Eq. 8 in the stretch rate equation Eq. 3, the following expression results

where the tangential component st = − 2Dhm is written explicitly in terms of curvature to highlight the non-linear contribution of the term \(2 s_{t} h_{m} = - 4 D {h_{m}^{2}}\) towards the stretch rate.

The normalized variation of overall stretch rate \(\dot {s}\) and its components across the instantaneous turbulent flame brush is shown in Fig. 8. Figure 8a shows the variation of strain rate, while the components of propagation rate sdhm are shown grouped separately as: 1) the sum of normal and reaction propagation rates snhm + srhm (Fig. 8b) and the tangential propagation rate sthm (Fig. 8c). The variation of the overall stretch rate is shown in Fig. 8d. The profiles are coloured based on the turbulence intensity (red squares: low-intensity, blue squares: moderate-intensity, and green squares: high intensity).

The variation of strain rate at across the instantaneous flame brush is shown in Fig. 8a. Consistent with the vertical lines in Fig. 2a and b, the (normalized) strain rate has a (slightly) positive mean conforming with previous investigations [24]. The spread of the distribution about zero increases with turbulence intensity (red through blue to green squares). This spread is greater near the leading edge 0.05 < c < 0.2. The increased spread in the leading edge region suggests that the turbulent flow upstream has higher vorticity possibly as it is prior to suppression by dilatation across the flame [27]. This is consistent with the Thin Reaction Zones regime.

The combination srhm + snhm tends to be negative in the preheat zone 0.05 < c < 0.6 and slightly positive in the reaction zone 0.6 < c < 0.95 region (red squares in Fig. 8b). This trend is more apparent at higher intensities (blue and green squares in Fig. 8b). The tangential component sthm, however, is always negative (\(- 4 D {h_{m}^{2}} < 0 \forall h_{m} \in \mathbb {R}, D \in \mathbb {R}^{+}\)), and the range of sthm increases with turbulence intensity (see green squares in Fig. 8c). The mean values of sthm (horizontal lines in Fig. 8c) become increasingly negative with increasing u′. It is evident, therefore, that the contribution of sthm increases in magnitude with u′ and it does not average out overall (right panel). Rather, it is the contribution of srhm + snhm that tends to average out over the flame brush (horizontal lines in Fig. 8b). This provides a contrasting data point with respect to various approaches for modelling the stretch rate that consider the curvature contribution sthm to cancel out in the mean [5], and provides support for more recent investigations that highlight its importance [13].

The variation of overall stretch rate \(\dot {s}\) is shown in Fig. 8d. For all three cases (red: low u′, blue: moderate u′, and green: high u′), the overall stretch rate has both positive and negative contributions. At low turbulence intensities (red squares), the most frequent contribution is from low positive stretch. This contribution appears to increase gradually across the instantaneous flame brush (low to high values of c in Fig. 8d). Negative contributions arise from fewer regions in the flame brush (red squares below horizontal line). At higher intensities (blue and green squares), this profile of stretch rates seems to follow with a much wider spread of stretch rates.

4.2 Implications for flamelet modelling

The results discussed above have some interesting implications with regard to the modelling of turbulent premixed flames in the context of the Flame Surface Density (FSD) approach [3, 4, 11] and related flamelet-based modelling approaches.

Firstly, there appears to be no qualitative change in the statistical behaviour of the displacement speed and its separate components as the turbulence intensity u′ is increased over the range considered here (as per Fig. 3). Even though the scatter in all quantities increases with u′ as might be expected, no new correlations are seen to emerge. This implies that a well-formulated FSD model should be applicable equally across the range of u′ spanning the TRZ regime.

Secondly, accurate modelling of the displacement speed appears to be a requirement in order to capture the non-linearities observed in the stretch rate and its components. Indeed, separate models may be needed for each of the three components of displacement speed, owing to their rather different response to strain and curvature (as per Figs. 6 and 7). Previous modelling [13, 17] has gone some way towards achieving this goal, but more work is needed still.

5 Conclusions

Joint probability density functions of mean curvature and displacement speed as well as stretch rate and displacement speed have been extracted from a DNS database wherein turbulence intensity is increased successively over five separate simulations. The shapes of both of these joint PDFs show little variation across the range of turbulence intensities in the Thin Reaction Zones regime. The distributions show a branched shape akin to previous observations in lean [9] as well as stoichiometric [20] methane-air flames. Components of displacement speed and, in particular, the tangential component through its dependence on curvature appears to play a significant role in effecting the branched structure of the distribution. The inherent non-linearities involved in the expression for stretch rate indicate that the recursive relationship between stretch rate and displacement speed is a worthy topic of further investigation.

References

Kostiuk, L., Bray, K.N.C.: Mean stretch effects on laminar flamelets in a turbulent premixed flame. Combust. Sci. Technol. 95, 193 (1994)

Williams, F.A.: Combustion Theory, 2nd edn. Westview Press (1985)

Pope, S.B.: The evolution of surfaces in turbulence. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 26, 445 (1988)

Candel, S., Poinsot, T.: Flame stretch and the balance equation for the flame area. Combust. Sci. Technol. 70, 1 (1990)

Bradley, D., Lau, A.K.C., Lawes, M., Smith, F.T.: Flame stretch rate as a determinant of turbulent burning velocity. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 338, 359 (1992)

Yeung, P.K., Girimaji, S.S., Pope, S.B.: Straining and scalar dissipation on material surfaces in turbulence: Implications for flamelets. Combust. Flame 79, 340 (1990)

Echekki, T., Chen, J.H.: Unsteady strain rate and cuvature effects in turbulent premixed methane-air flames. Combust. Flame 106, 184 (1996)

Peters, N., Terhoeven, P., Chen, J.H., Echekki, T.: Statistics of flame displacement speeds from computations of 2-d unsteady methane-air flames. In: 27th Symposium (International) on Combustion, pp. 833–839 (1998)

Chen, J.H., Im, H.: Correlation of flame speed with stretch in turbulent premixed methane/air flames. In: 27th Symposium (International) on Combustion, pp. 819–826 (1998)

Trouvé, A., Poinsot, T.: The evolution equation for the flame surface density in turbulent premixed combustion. J. Fluid Mech. 278, 1 (1994)

Cant, R.S., Rutland, C., Trouvé, A.: In: Studying Turbulence Using Numerical Simulation Databases, vol. 3: Proceedings of the 1990 Summer Program, pp. 271–279 (1990)

Bradley, D., Gaskell, P.H., Gu, X.J., Sedaghat, A.: Premixed flamelet modelling: factors influencing turbulent heat release rate source term and the turbulent burning velocity. Combust. Flame 143, 227 (2005)

Hawkes, E., Chen, J.: Evaluation of models for flame stretch due to curvature in the thin reaction zones regime. Proc. Combust. Inst. 30, 647 (2005)

Chakraborty, N., Cant, R.S.: Unsteady effects of strain rate and curvature on turbulent premixed flames in an inflow-outflow configuration. Combust. Flame 137, 129 (2004)

Sankaran, R., Hawkes, E.R., Chen, J.H., Lu, T., Law, C.K.: Structure of a spatially developing turbulent lean methane-air bunsen flame. Proc. Combust. Inst. 31, 1291 (2007)

Wang, H., Hawkes, E.R., Chen, J.H., Zhou, B., Li, Z., Aldén, M.: Direct numerical simulations of a high Karlovitz number laboratory premixed jet flame – an analysis of flame stretch and flame thickening. J. Fluid Mech. 815, 511 (2017)

Chakraborty, N., Cant, R.S.: A priori analysis of the curvature and propagation terms of the flame surface density transport equation for large eddy simulation. Phys. Fluids 19, 105101 (2005)

Lapointe, S., Savard, B., Blanquart, G.: Differential diffusion effects, distributed burning, and local extinctions in high Karlovitz premixed flames. Combust. Flame 162, 3341 (2015)

Clavin, P., Williams, F.A.: Effects of molecular diffusion and of thermal expansion on the structure and dynamics of premixed flames in turbulent flows of large scale and low intensity. J. Fluid Mech. 116, 251 (1982)

Chakraborty, N., Klein, M., Cant, R.S.: Stretch rate effects on displacement speed in turbulent premixed flame kernels in the thin reaction zones regime. Proc. Combust. Inst. 31, 1385 (2006)

Nikolaou, Z.M., Swaminathan, N.: Direct numerical simulation of complex fuel combustion with detailed chemistry: physical insight and mean reaction rate modeling. Combust. Sci. Technol. 187, 1759 (2015)

Nivarti, G.V., Cant, R.S.: Direct numerical simulation of the bending effect in turbulent premixed flames. Proc. Combust. Inst. 36, 1903 (2017)

Nivarti, G.V., Cant, R.S.: Scalar transport and the validity of Damköhler’s hypotheses for flame propagation in intense turbulence. Phys. Fluids 29, 085107 (2017)

Bray, K.N.C., Cant, R.S.: Some applications of Kolmogorov’s turbulence research in the field of combustion. Proc. R. Soc. London A: Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 434, 217 (1991)

Gran, I.R., Echekki, T., Chen, J.H.: Negative flame speed in an unsteady 2-d premixed flame: a computational study. In: 26th Symposium (International) on Combustion, pp. 323–329 (1996)

Peters, N.: The turbulent burning velocity for large-scale and small-scale turbulence. J. Fluid Mech. 184, 107 (1999)

Aspden, A.: A numerical study of diffusive effects in turbulent lean premixed hydrogen flames. Proc. Combust. Inst. 36, 1997 (2017)

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Alan Kerstein for the helpful discussions towards the present work. GVN acknowledges the funding support of EPSRC grant EP/P022286/1. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Nivarti, G.V., Cant, R.S. Stretch Rate and Displacement Speed Correlations for Increasingly-Turbulent Premixed Flames. Flow Turbulence Combust 102, 957–971 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10494-018-9990-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10494-018-9990-7