Abstract

The experiences of individuals with mental illness and addictions who frequently present to hospital emergency departments (EDs) have rarely been explored. This study reports findings from self-reported, quantitative surveys (n = 166) and in-depth, qualitative interviews (n = 20) with frequent ED users with mental health and/or substance use challenges in a large urban centre. Participants presented to hospital for mental health (35 %), alcohol/drug use (21 %), and physical health (39 %) concerns and described their ED visits as unavoidable and appropriate, despite feeling stigmatized by hospital personnel and being discharged without expected treatment. Supporting this population may require alternative service models and attention to staff training in both acute and community settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In most jurisdictions, a small number of individuals account for a disproportionately high number of visits to hospital Emergency Departments (EDs) (LaCalle and Rabin 2010; Vandyk et al. 2013). This heterogeneous population, often identified as “frequent (ED) users” (Vandyk et al. 2013), has been commonly found to experience multiple medical and social vulnerabilities, including mental illness and/or addictions (Byrne et al. 2003; Fuda and Immekus 2006; Mehl-Madrona 2008; Pines et al. 2011; Vandyk et al. 2013).

The experiences of frequent users as an undifferentiated group have been examined qualitatively (Malone 1996; Mautner et al. 2013; Olsson and Hansagi 2001), although as Mautner et al. (2013) assert, “the patient perspective is rarely represented” in previous studies of this population. Similarly, while the subpopulation of frequent users with mental health and substance use concerns has been well-described (Byrne et al. 2003; Doupe et al. 2012; Minassian et al. 2013; Vandyk et al. 2013), research exploring their experiences of ED utilization—described in their own voices—is notably absent. It has been previously suggested that the subgroup of frequent users with mental health and addictions related concerns, reflecting the pervasive stereotype of “the psychiatric, drug-seeking or non-urgent frequent user” (LaCalle and Rabin 2010), requires more attention by qualitative researchers (Pines et al. 2011). In particular, we know very little about the precipitants of, perceived alternatives to, and experiences of ED utilization of this subpopulation of frequent users.

In a recent review of the qualitative literature on ED presenters, Gordon et al. (2010) found that patients tend to perceive their presenting issues as “serious or life threatening” and reveal a common thread of negative experiences when their visits are deemed “inappropriate.” Nairn et al. (2004) noted that the literature on patient experiences in the ED is dominated by quantitative studies, and that more qualitative research would enrich understanding. More recently, in small qualitative studies, researchers have described the experiences of the general population of ED presenters, (Olthuis et al. 2014; Wellstood et al. 2005), while also emphasizing the preponderance of quantitative studies in this area of inquiry.

Given the scant qualitative research on patient experiences in the ED, and in particular, the lack of attention to frequent users with mental health and/or addictions challenges, the aim of this study was to explore perceived need for and experiences of ED utilization of this subpopulation of frequent users in a large urban centre. Across jurisdictions, understanding and reducing frequent ED utilization is a priority consideration in efforts to both improve timely access to appropriate community-based services and reduce healthcare costs. Frequent ED users with mental health and addiction challenges, a diagnostically heterogeneous population, are in dire need of further understanding to help guide appropriate interventions and improve their health care experiences and service use outcomes.

Methods

The Setting

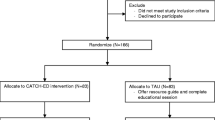

The Coordinated Access to Care from Hospital Emergency Departments (CATCH-ED) study was a randomized controlled trial of a brief case management intervention for frequent users with mental health and addictions challenges. The study was conducted in Toronto, Canada, where there is universal coverage for physician and hospital care through the publicly-funded Canadian health care system. The CATCH-ED study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01622244).

In summary, participants (N = 166) were adults with five or more visits in the past year to one of six participating hospital EDs, with at least one visit for a mental health or substance use-related concern. Participants were randomized to the intervention or Treatment as Usual (TAU), and followed for 12 months.

Data Collection and Analysis

All 166 participants from the intervention and TAU groups met a member of the research team at baseline and at 3-month intervals over 12 months to complete quantitative survey questionnaires. We used descriptive statistics to summarize baseline self-reported data on health service utilization and precipitants of ED use over the previous 6 months.

A subset of 20 participants from the intervention group was sampled purposively among successive study referrals. We aimed to recruit participants able to offer rich narratives of their experiences, ensuring recruitment of participants from all six participating EDs. We recruited sequentially among each case manager caseload until we reached the target number of 20 participants. Three potential participants among those invited refused participation.

Prospective participants were invited to complete an in-depth qualitative interview, 6-months after study enrolment, between August 2013 and December 2013. The interviews were conducted by one member of the research team with lived experience of mental illness, using a semi-structured interview guide with open-ended questions and probes. For the purposes of this study, we explored participants’ reasons for and experiences of ED utilization, including questions focused on their narratives of accessing services and supports. All 20 participants provided written, informed consent.

The interviews ranged from 30 to 90 min in length, and were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Thematic analysis was used to analyze the transcripts (Braun and Clarke 2006; Morse and Field 1995). The process of coding segments of the data into themes followed the constant comparative method derived from grounded theory methodology and involved classifying, comparing, grouping, and refining the emerging themes (Fossey 2002; Glaser and Strauss 1967; Morse and Field 1995).

Two members of the research team (DWH, DP) double-coded five transcripts, and met to compare codes and discuss emerging themes. The remaining transcripts were coded independently by one member of the research team (DWH), and the analysis was further developed by three members of the research team (DP, DK, VS). The research team maintained an audit trail documenting the data collection and analysis process and used QSR NVivo 10 software to manage and analyze the data.

Results

Among all 166 study participants, the median age was 44.5 years (IQR 32.6–56.3) and half were male (51 %). Participants had a median of 6 ED visits (IQR 4.0–10.0) and 3.0 days in hospital (3.0) (IQR 0.0–17.0) in the 6 months prior to enrolment, based on self-reported data. Seventy-nine percent (n = 130) of the sample indicated they had a regular medical doctor. Approximately two third (65 %) of participants reported a diagnosis of a mood disorder, while 29 % reported a psychotic illness, 42 % a concurrent alcohol use disorder and 28 % a substance use disorder. Participants were predominantly Canadian born (74 %), Caucasian (67 %), single/never married (64 %), and in receipt of disability benefits (75 %). The majority (68 %) had three or more comorbid chronic health conditions. Only 10 % of participants had a history of homelessness in the previous 12 months. Tables 1 and 2 present self-reported health care utilization and reasons for ED use at baseline, respectively, for both the total sample, and the subset of 20 narrative interview participants.

Self-reported survey data revealed multiple precipitants of ED use in the previous 6 months, including mental health concerns (35 %), alcohol or drug use (21 %) and comorbid physical health (39 %)-related concerns.

These precipitants were further explored in the narrative data, described in the sections that follow. Frequent users’ perspectives exposed a perceived clash of viewpoints among patients, community support providers, and ED personnel as to the appropriateness of the ED as a point of care for this population. Additional emerging themes, described below, further highlighted largely negative experiences of ED care among participants, including perceived stigma, discrimination, and unsympathetic care.

A Diversity of Precipitants

Study participants described a diversity of challenges precipitating their ED use, which is not surprising, given the complexity of their health needs. Common presenting issues included both mental health and substance use-related concerns, as well as acute and chronic health conditions. Regarding mental health concerns, several of the participants attributed their ED use to acute mental health crises associated with suicide attempts and suicidal ideation. One participant described her reasons for presenting at the ED as follows: “…my car accident happened and I had the most severe depression of my life, like I had serious very frequent suicidal attempts and issues and I was at [the hospital] all the time.” (01)

Others described persistent mental health symptoms such as depression, anxiety and psychosis, including this participant: “I went to the emergency room a lot. I was triggered a lot. I had psychosis so whenever I had psychosis I would go to the emergency room.” (42)

Substance use and associated physical health sequelae, such as falls, dehydration or intoxication, were additional precipitants for ED use, with alcohol being the most commonly referenced substance. As one participant described:

“[The Emergency Department] kind of feels like a second home…I don’t know what happens to me usually when I get into Emerg. … most of the time I’m not alert for it so I really have no recollection. Like, I go in with a bottle…Most of the time my bottle gets taken away from me somewhere along the line… Then I wake up, finally, after 7/8 hours and my bottle’s gone and they’re talking to me about getting help. Yeah—that’s normal there for me.” (111)

Among those visiting for comorbid acute and chronic physical health conditions, complaints of pain and injury were common, as for this participant: “I have sciatic nerve damage down … my whole right side and it causes me not to be able to walk or sit down or anything and so that’s why I would end up in emerg all the time.” (92)

Are ED Visits Avoidable? A Clash of Viewpoints

One of the main themes in our participant’s narratives was a perceived clash of viewpoints among patients, community service providers, and ED personnel as to the appropriateness of the ED as a point of care for mental health and substance use crises. In effect, this clash represented disagreement about whether or not ED use was avoidable in the current service delivery context. We describe below frequent users’ perspectives on their use of the ED, and conflicting messages received regarding this use.

An Unavoidable and Appropriate Destination: Frequent Users’ Perspectives

Many participants perceived their ED visits as unavoidable, because they thought their health concerns required immediate help. As one participant described: “I’ll die if I don’t come here… it’s not like you know…a broken bone where it might set the wrong way, it’s like you just die; …it’s just I don’t have a choice.” (15) Other participants similarly asserted that their visits are not precipitated by trivial concerns: “I felt that it was justified like I didn’t [go] for fun … like I did try distractions and other methods before that.” (08)

Participants also viewed their frequent ED visits as resulting from a lack of alternative, accessible destinations within the existing health care system. This was particularly true for participants who lacked family and other social supports, like this participant: “The first panic attack I had … I just like my whole left hand felt really numb and I felt just like fainting so I didn’t know what was going on…I couldn’t turn to my parents for help or anyone, so the only decision was to go to the hospital.” (16)

Participants familiar with a local crisis centre and crisis resources such as crisis phone lines and mobile crisis teams, repeatedly suggested that those are unsatisfactory alternatives to the ED. As this participant explained: “I find that [the crisis centre] will turn you away if they think you are not in a real crisis and like they get to decide what’s a real crisis and what’s not a real crisis and then if they think you are not in a real crisis, they can turn you away.” (42) Other participants explained why a crisis line in the community did not meet their needs, as was the case for this participant: “I phoned 2 or 3 times down there to see…I, with post-traumatic stress…I can’t talk to 5 or 10 different people because it’s just too emotional.” (31)

Although the majority of participants had access to primary care in the community, and approximately half received psychiatric care, several participants understood their frequent ED visits as resulting from a lack of timely access or an interruption to these community-based services. As one participant explained: “A lot of them told me to wait until I see my psychiatrist but …I was getting visits very infrequently and I’d have to wait a matter of weeks and or she’d be away and have no replacement.” (60)

Some participants also suggested that the ED can serve as an expedient gateway to other services—addiction services in particular—that are otherwise difficult to access. As this participant explained, “I know that if I go to an emergency…that they can pretty much send you directly to a detox. So, and that’s recognized in, that some cultures as being the way to get into a detox.” (98)

Reinforcers of Emergency Department Use: Societal Perceptions and Community-Provider Endorsements

As described above, many participants viewed the ED as the appropriate point of care for their concerns. Furthermore, participants perceived their viewpoint as being supported or shared by their social supports and community health care providers, including primary care providers. Participants’ feeling that their repeat visits were socially endorsed contributed to their understanding of the ED as the normative and appropriate destination for people in mental health, pain and substance use crises. As one participant who experienced frequent suicidal feelings put it: “I don’t know why I go. Everybody in the outside world thinks that I need to be there … people get nervous because I think they feel they have a certain obligation to get that person help so, I think they do what they know what to do…which is to send me to [the hospital]”… (01)

Participants also reported receiving support and direction from community-based providers to visit the ED. Service providers in the community, including physicians, therapists, social workers and the local crisis centre, were seen as sanctioning, and in some cases, “forcing” these individuals to go to the ED by calling police or ambulance or by accompanying them to hospital. As this participant described: “I had to go to the ED by force…I had to go and even try to talk my worker down from it and she’s like ‘no, you have to go in, now’ and…so I went in.” (25)

Conflicting Messages in the Emergency Department

According to participants, hospital personnel often gave conflicting messages about the appropriateness of the ED as a destination for their concerns. One participant described an exchange with an ED physician highlighting the tension between the patient’s belief that the hospital was the right destination and a conflicting organizational viewpoint: “[The Emergency Department doctor] agrees it’s like ‘yeah I know, we get a lot of patients like this, people think that we do something very magical and …just fix things and it’s just not the way it works here.’ … he just sent me home so quickly.” (01)

Participants and hospital staff sometimes disagreed about what constitutes an “emergency.” One participant described it this way: “I just went [to the Emergency Department] recently and they said it’s not an emergency and they let me out” (42), while another participant explained the disjuncture between her perception and the hospital staff’s opinion: “It’s kind of scary because you don’t know what’s going on in your body but you feel like it’s an emergency. But then when you get there they will like tell you nothing is really going on or we don’t know what the issue is.” (16)

The experience of being seen as using the ED inappropriately left some participants feeling ashamed: “…I just started feeling ashamed of going there so much and needing the help…every time I’d think of going …I like wanted to commit suicide… well they’re not going to believe me, they’re not going to do anything so, the shame was from their thinking I am lying or an attention seeker, it’s pretty disappointing.”(08)

Negative Experiences of Care in the Emergency Department

Participants spoke overwhelmingly about negative experiences of care in the ED that nonetheless did not prevent them from returning. These negative experiences clustered around the themes of stigma and discrimination, and perfunctory and unsympathetic care.

Stigma and Discrimination

Participants reported feeling stigmatized by hospital personnel due to the frequency of their ED visits or their mental health and/or addictions challenges. In terms of frequency of visits, participants described being met with impatience from hospital staff, including being told: “Oh, you’re back again” (60), “Oh, you were just here” (15), and “Oh boy, she’s here again” (111). Some participants spoke of the staff being “tired” (04, 83) of seeing them in the ED, particularly when they presented for substance use-related physical health concerns.

Regarding their mental health or addiction concerns, participants described experiencing stigmatizing treatment, with one participant reporting being viewed as “just a psych case” (15). Addictions-related stigma was even more commonly described by participants: “I find too that as being an addict, an alcoholic, that sometimes there seems to be … that there’s stigma and some prejudices are imposed on me” (98).

Other participants described being asked to wait in the ED for long periods and interpreted this waiting as a form of discrimination: “They would kind of just examine me but I noticed like when I went more often it would just be really short visits or like …the waiting time would be so long that I would be just frustrated and I would leave… Frustrated because I felt like going to the hospital was a safe place but I felt like I wasn’t receiving the help I needed.” (26)

Perfunctory and Unsympathetic Care

Participants attributed perceived perfunctory or superficial treatment in the ED to their frequency of visits. As one participant described: “… I was leaving, I see him grab his stuff and dart out the door, it was like the end of his shift and I think he just wanted to go home and so, he was just really quick with me and that’s why I was like, oh, that’s why this whole thing was 3 min because I have been there so many times.” (01)

Some participants described being discharged without having their concerns addressed. They spoke of having been “dismissed” (60), “kicked out” (08) and sent on their way (38, 26). They described both a circle of “being sent in and out” (26) without treatment or resolution and a “revolving door” (25, 98) that perpetuated their return to the ED. As one participant noted: “They ignored my needs and my request and quite often that’s been the case where it just seems like … they want to process me and go out and see your family doctor or whatever.” (98)

These frequent users often described being treated unsympathetically and depicted ED personnel as “nasty” (01, 25, 87), “rude” (4, 24, 83), “smug” and “sarcastic” (31), “not always caring” (38) and “pretty cold like they don’t care” (42). One participant described ED nurses as having “lost that loving feeling” (4) and a number of other participants reported feeling unwelcome, such as the participant below: “There was that undertone all the time … every time walking me out the door, you’re always welcome back … I guess it’s their legal kind of thing, you can always come back, we’re here for you … but we actually don’t want you here.” (08)

Discussion

Frequent users of EDs often experience complex vulnerabilities, including mental health and substance use challenges, and comorbid medical conditions (LaCalle and Rabin 2010; Vandyk et al. 2013). Our sample reflected this profile, reporting complex health needs and a diversity of precipitants of ED use, including mental health, substance use and physical health concerns. It is well-documented that most frequent users have community-based primary care (Howard et al. 2005; Hunt et al. 2006; Lucas and Sanford 1998), and our participants were no exception. They identified challenges in timeliness of access and continuity of care as well as a lack of accessible, acceptable alternatives for mental health or addictions-related crises, even within a large urban centre and a system of universal health insurance.

Participant perceptions that ED visits are unavoidable echo those from the general population of frequent users (Gordon et al. 2010; LaCalle and Rabin 2010; Webster et al. 2015), who similarly identified the ED as the perceived unavoidable point of care in many service delivery contexts.

Our findings both support and are supported by previous research on frequent or repeat ED users, highlighting that patients are often encouraged to seek care in the ED by community-based providers (Vandyk et al. 2013; Young et al. 1996) or by friends and family (Rising et al. 2015). Seeking care in EDs may be reinforced by outgoing messages on health care providers’ voice mails routinely encouraging patients to present to the ED in case of an emergency.

The participants’ view of unavoidable ED utilization, reinforced by their support networks, appeared to conflict with that of hospital personnel, as described in their narratives. In the realm of increasing healthcare costs and health system sustainability, the question of frequent or repeat ED use is sometimes framed by rhetoric about the inappropriateness of such visits (Hunt et al. 2006; Pines et al. 2011; Rising et al. 2015), and hospital personnel views and attitudes may reflect this rhetoric and belief (Gill 1994; Malone 1996; Nystrom et al. 2003). The discourse of inappropriate use has recently been the subject of critique (Affleck et al. 2013; Bernstein 2006; LaCalle and Rabin 2010; Lowe and Schull 2011). Lacalle and Rabin (2010), for instance, found that frequent users tend to have more acute concerns than non-frequent users. In addition, past studies of perceived urgency in the ED have shown that patients and hospital personnel disagree about what constitutes an “appropriate” ED visit (Gill et al. 1996). We concur with Olthuis et al. (2014) that the “mismatch” between the ED patient’s concerns and the staff’s responses requires further investigation, if we are to better understand and meet patient needs and preferences, and design alternative services and supports aimed at curbing frequent ED use (Althaus et al. 2011; Kumar and Klein 2013; Soril et al. 2015).

A second main theme in our data is participants’ perception of poor treatment in the ED, including experiences of stigma and discrimination and perfunctory and unsympathetic care. Participants often interpreted their routine discharge as poor treatment. In her qualitative review of patient satisfaction in the ED, Welch (2010) also found that patients may feel unsatisfied when they are sent home without being admitted or treated. Clarke et al. (2007) described a dichotomy between the mental health patient seeking admission to hospital, and ED clinicians who see diversion to community services as the more successful outcome. This disagreement on successful care outcomes, also observed in our study, contributes to potentially strained and combative relationships between patients and providers. It may suggest a need for training to sensitize hospital staff to factors impacting frequent use, patient experiences, and the importance of referral to timely, appropriate aftercare.

Participants in this study described the experience of stigmatization and discrimination by hospital personnel as a result both of their mental health and/or addictions challenges, and their repeated visits. Evidence of perceived stigmatization and stereotyping of patients with mental illness by health care providers is growing (Clarke et al. 2007; Pope 2011; Skosireva et al. 2014). While previous inquiry into the ED experiences of frequent users revealed perceived ageism (Olsson and Hansagi 2001), racism (Nairn et al. 2004), sexism, and discrimination based on socioeconomic status, the experience of discrimination based specifically on mental health status and substance use has not been previously exposed for this subpopulation. Further exploration into the impact of perceived stigma and discrimination on health care utilization for this population is warranted in both acute and non-acute care settings.

Previous research has highlighted that the caring competence of hospital staff is associated with positive care experiences for ED users (Gordon et al. 2010; Mautner et al. 2013; Welch 2010). Our findings of predominantly negative ED experiences among our participants, in the context of perceived lack of caring by hospital staff, are therefore not surprising.

Redelmeier et al. (1995) studied the impact of providing compassionate care on frequent ED use by homeless adults in an urban hospital in Toronto, Canada. They found that by incorporating compassionate care by trained volunteers, homeless adults were more satisfied with their care experience, and used EDs less frequently. Their findings both challenge the perspective that increased patient satisfaction may encourage frequent visits, and suggest that greater caring attention has the potential to decrease ED utilization. Institutional and departmental policies to address staff burnout and compassion fatigue, including investing in training for hospital staff to promote compassionate and non-stigmatizing care for individuals with mental health and addiction challenges, including frequent users of EDs, might improve the patient experience and reduce service use (Crowley 2000; Maslach and Goldberg 1998; Potter 2006; Welch 2010).

Study Limitations

Despite its strengths in addressing knowledge gaps and offering insights on frequent ED users with mental health and addiction challenges, our study has some limitations. First, our sample size of 20 participants from a single urban centre limits generalizability. Frequent users with mental health and substance use challenges are a heterogeneous population, and it is possible that the characteristics of our sample differ from those of their counterparts in other jurisdictions. Nonetheless, our findings parallel others’ in related literature and are likely to be relevant to many jurisdictions and service delivery contexts seeking to address frequent ED utilization. Second, we set out to explore patient experiences in their own voices, and did not elicit perspectives and experiences of hospital staff, the focus of future work in this area. Last, but not least, homeless individuals are under-represented in our sample, as these individuals had access to alternative community services and did not meet eligibility criteria for the parent study, from which our sample is drawn. Experiences of homeless individuals with mental illness in hospital settings is also an area of forthcoming work.

Conclusions

This study, exposing the profile, perspectives and experiences of frequent users of EDs with mental health and addiction challenges, is an important first step in efforts to design appropriate, alternative community-based services and supports, and improve ED experiences and outcomes. Our findings highlight the need for further exploration of barriers to care in alternative community-based settings for this population, as well as the need for appropriate training and support of health care providers to address complex physical and mental health needs, improve patient experiences and combat pervasive stigma and discrimination.

References

Affleck, A., Parks, P., Drummond, A., Rowe, B. H., & Ovens, H. J. (2013). Emergency department overcrowding and access block. CJEM, 15(06), 359–370.

Althaus, F., Paroz, S., Hugli, O., Ghali, W. A., Daeppen, J.-B., Peytremann-Bridevaux, I., & Bodenmann, P. (2011). Effectiveness of interventions targeting frequent users of emergency departments: A systematic review. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 58(1), 41–52. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.007. e42.

Bernstein, S. L. (2006). Frequent emergency department visitors: The end of inappropriateness. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 48(1), 18–20. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.03.033.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Byrne, M., Murphy, A. W., Plunkett, P. K., McGee, H. M., Murray, A., & Bury, G. (2003). Frequent attenders to an emergency department: A study of primary health care use, medical profile, and psychosocial characteristics. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 41(3), 309–318. doi:10.1067/mem.2003.68.

Clarke, D. E., Dusome, D., & Hughes, L. (2007). Emergency department from the mental health client’s perspective. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 16(2), 126–131. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0349.2007.00455.x.

Crowley, J. J. (2000). A clash of cultures: A&E and mental health. Accident and Emergency Nursing, 8(1), 2–8. doi:10.1054/aaen.1999.0061.

Doupe, M. B., Palatnick, W., Day, S., Chateau, D., Soodeen, R., Burchill, C., et al. (2012). Frequent users of emergency departments: Developing standard definitions and defining prominent risk factors. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 60(1), 24–32.

Fossey, E. (2002). Understanding and evaluating qualitative research. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 36(6), 717–732.

Fuda, K. K., & Immekus, R. (2006). Frequent users of Massachusetts emergency departments: A statewide analysis. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 48(1), 9–16. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.03.001.

Gill, J. M. (1994). Nonurgent use of the emergency department: Appropriate or not? Annals of Emergency Medicine, 24(5), 953–957. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(94)70213-6.

Gill, J. M., Reese, C. L, 4th, & Diamond, J. J. (1996). Disagreement among health care professionals about the urgent care needs of emergency department patients. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 28(5), 474–479. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(96)70108-7.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine.

Gordon, J., Sheppard, L. A., & Anaf, S. (2010). The patient experience in the emergency department: A systematic synthesis of qualitative research. International Emergency Nursing, 18(2), 80–88. doi:10.1016/j.ienj.2009.05.004.

Howard, M. S., Davis, B. A., Anderson, C., Cherry, D., Koller, P., & Shelton, D. (2005). Patients’ perspective on choosing the emergency department for nonurgent medical care: A qualitative study exploring one reason for overcrowding. Journal of Emergency Nursing: JEN, 31(5), 429–435. doi:10.1016/j.jen.2005.06.023.

Hunt, K. A., Weber, E. J., Showstack, J. A., Colby, D. C., & Callaham, M. L. (2006). Characteristics of frequent users of emergency departments. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 48(1), 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.12.030.

Kumar, G. S., & Klein, R. (2013). Effectiveness of case management strategies in reducing emergency department visits in frequent user patient populations: A systematic review. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 44(3), 717–729.

LaCalle, E., & Rabin, E. (2010). Frequent users of emergency departments: The myths, the data, and the policy implications. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 56(1), 42–48. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.01.032.

Lowe, R. A., & Schull, M. (2011). On Easy solutions. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 58(3), 235–238. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.054.

Lucas, R. H., & Sanford, S. M. (1998). An analysis of frequent users of emergency care at an urban university hospital. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 32(5), 563–568.

Malone, R. E. (1996). Almost “like family”: Emergency nurses and “frequent flyers”. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 22(3), 176–183. doi:10.1016/S0099-1767(96)80102-4.

Maslach, C., & Goldberg, J. (1998). Prevention of burnout: New perspectives. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 7(1), 63–74. doi:10.1016/S0962-1849(98)80022-X.

Mautner, D. B., Pang, H., Brenner, J. C., Shea, J. A., Gross, K. S., Frasso, R., & Cannuscio, C. C. (2013). Generating hypotheses about care needs of high utilizers: Lessons from patient interviews. Population Health Management, 16(Suppl 1), S26–S33. doi:10.1089/pop.2013.0033.

Mehl-Madrona, L. E. (2008). Prevalence of psychiatric diagnoses among frequent users of rural emergency medical services. Canadian Journal of Rural Medicine: The Official Journal of the Society of Rural Physicians of Canada = Journal Canadien De La Médecine Rurale: Le Journal Officiel De La Société De Médecine Rurale Du Canada, 13(1), 22–30.

Minassian, A., Vilke, G. M., & Wilson, M. P. (2013). Frequent emergency department visits are more prevalent in psychiatric, alcohol abuse, and dual diagnosis conditions than in chronic viral illnesses such as hepatitis and human immunodeficiency virus. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 45(4), 520–525. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.05.007.

Morse, J. M., & Field, P. A. (1995). Qualitative research methods for health professionals. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

Nairn, S., Whotton, E., Marshal, C., Roberts, M., & Swann, G. (2004). The patient experience in emergency departments: A review of the literature. Accident and Emergency Nursing, 12(3), 159–165. doi:10.1016/j.aaen.2004.04.001.

Nystrom, M., Dahlberg, K., & Carlsson, G. (2003). Non-caring encounters at an emergency care unit—a life-world hermeneutic analysis of an efficiency-driven organization. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 40(7), 761–769. doi:10.1016/S0020-7489(03)00053-1.

Olsson, M., & Hansagi, H. (2001). Repeated use of the emergency department: Qualitative study of the patient’s perspective. Emergency Medicine Journal, 18(6), 430–434. doi:10.1136/emj.18.6.430.

Olthuis, G., Prins, C., Smits, M.-J., van de Pas, H., Bierens, J., & Baart, A. (2014). Matters of concern: A qualitative study of emergency care from the perspective of patients. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 63(3), 311–319. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.08.018. e2.

Pines, J. M., Asplin, B. R., Kaji, A. H., Lowe, R. A., Magid, D. J., Raven, M., et al. (2011). Frequent users of emergency department services: Gaps in knowledge and a proposed research agenda. Academic Emergency Medicine, 18(6), e64–e69. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01086.x.

Pope, W. S. (2011). Another face of health care disparity: Stigma of mental illness. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 49(9), 27–31. doi:10.3928/02793695-20110802-01.

Potter, C. (2006). To what extent do nurses and physicians working within the emergency department experience burnout: A review of the literature. Australasian Emergency Nursing Journal, 9(2), 57–64. doi:10.1016/j.aenj.2006.03.006.

Redelmeier, D., Molin, J. P., & Tibshirani, R. J. (1995). A randomised trial of compassionate care for the homeless in an emergency department. The Lancet, 345, 1131–1134.

Rising, K. L., Padrez, K. A., O’Brien, M., Hollander, J. E., Carr, B. G., & Shea, J. A. (2015). Return visits to the emergency department: The patient perspective. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 65(4), 377–386. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.07.015. e3.

Skosireva, A., O’Campo, P., Zerger, S., Chambers, C., Gapka, S., & Stergiopoulos, V. (2014). Different faces of discrimination: perceived discrimination among homeless adults with mental illness in healthcare settings. BMC Health Services Research, 14(1), 376. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-14-376.

Soril, L. J. J., Leggett, L. E., Lorenzetti, D. L., Noseworthy, T. W., & Clement, F. M. (2015). Reducing frequent visits to the emergency department: A systematic review of interventions. PLoS ONE, 10(4), e0123660. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0123660.

Vandyk, A. D., Harrison, M. B., VanDenKerkhof, E. G., Graham, I. D., & Ross-White, A. (2013). Frequent emergency department use by individuals seeking mental healthcare: A systematic search and review. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 27(4), 171–178. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2013.03.001.

Webster, F., Christian, J., Mansfield, E., Bhattacharyya, O., Hawker, G., Levinson, W., et al. (2015). Capturing the experiences of patients across multiple complex interventions: A meta-qualitative approach. BMJ Open, 5(9), e007664. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007664.

Welch, S. J. (2010). Twenty years of patient satisfaction research applied to the emergency department: A qualitative review. American Journal of Medical Quality, 25(1), 64–72. doi:10.1177/1062860609352536.

Wellstood, K., Wilson, K., & Eyles, J. (2005). “Unless you went in with your head under your arm”: Patient perceptions of emergency room visits. Social Science and Medicine, 61(11), 2363–2373. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.04.033.

Young, G. P., Wagner, M. B., Kellermann, A. L., Ellis, J., & Bouley, D. (1996). Ambulatory visits to hospital emergency departments. Patterns and reasons for use. 24 Hours in the ED Study Group. JAMA, 276(6), 460–465.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wise-Harris, D., Pauly, D., Kahan, D. et al. “Hospital was the Only Option”: Experiences of Frequent Emergency Department Users in Mental Health. Adm Policy Ment Health 44, 405–412 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-016-0728-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-016-0728-3