Abstract

Multi-component models for improving depression care target primary care (PC) clinics, yet few studies document usual clinic-level care. This case comparison assessed usual processes for depression management at 10 PC clinics. Although general similarities existed across sites, clinics varied on specific processes, barriers, and adherence to practice guidelines. Screening for depression conformed to guidelines. Processes for assessment, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up varied to different degrees in different clinics. This individuality of usual care should be defined prior to quality improvement interventions, and may provide insights for introducing or tailoring changes, as well as improving interpretation of evaluation results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

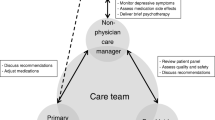

Effective and cost-effective multi-component models for improving depression outcomes in primary care use a coordinated set of strategies to improve depression care process and outcomes (Gilbody et al. 2003, 2006; Williams et al. 2007). Strategies target specific aspects of guideline concordant care (Schulberg et al. 1998; VHA/DOD 2000), providing support to primary care clinics for screening, assessing, diagnosing, treating, and following depressed patients, as well as improving coordination with mental health (MH) services. These collaborative care models target the clinic- or practice group-level rather than individual providers (Bruce et al. 2004; Lin et al. 2006; Oxman et al. 2002; Rubenstein et al. 1999; Unutzer et al. 2001). Most of the studies of these models are randomized trials that use “usual care” comparisons. Some quality improvement methods argue for pre-intervention practice assessment (Stroebel et al. 2005). There is little documentation in the literature, however, describing the details of usual care for depressed PC patients throughout the care process, the variations in the usual process that may occur between clinics within a system, or the barriers that may affect concordance of depression care with recommended clinical practice guidelines.

Wells et al. (1999), examined the process of depression care in visits with PC providers, and noted that rates of care varied among providers from different managed care organizations, suggesting the need for studying processes at the organizational level. But, recent studies that have described usual care by primary care providers (PCPs) have focused primarily on aspects of the process between an individual patient and provider (Hepner et al. 2007; Robinson et al. 2005; Solberg et al. 2005; Upshur 2005), especially antidepressant prescribing and management (Joo et al. 2005; Young et al. 2001), or other specific aspects of care, such as diagnosis and treatment (Liu et al. 2006). Other reports have described barriers to depression care (Nutting et al. 2002; Pincus et al. 2003) or barriers to implementing collaborative care models (Kilbourne et al. 2004), but not the process of care, per se.

Understanding existing conditions at the clinic level, especially gaps between current and desired practice, is crucial to planning and accomplishing the activities needed to improve processes of care. This study assesses the usual processes of care for depression management in ten primary care clinics, and barriers, in order to understand concordance with care guidelines as a basis for tailoring quality improvement activities. Our study questions ask which aspects of concordance with guidelines—considering screening, assessment, diagnosis, treatment, and referral—are in greatest need for improvement for each clinic, and which barriers to care identified by primary care and mental health leaders might provide guidance for remedying the areas of difficulty.

Methods

Design and Participants

We used a case comparison strategy (Stake 2003) to describe common patterns and particularities in the process of depression care in ten outpatient primary care practices. This cross-sectional study was one component of the pre-intervention phase of a multi-site implementation of a collaborative care model for depression treatment in primary care clinics. The implementation involved three VA multi-state administrative regions (Veterans Integrated Service Networks, or VISNs); regional leaders are responsible for financing and quality of all facilities within their network. We studied the ten VA primary care clinic sites (Table 1) from these regions that were involved in the implementation. The analyses reported here drew upon two types of data: qualitative descriptions of care processes from key informant interviews with clinical leaders from each clinic, supplemented by data from administrative sources describing organizational structures.

In the VA, each outpatient primary care clinic is associated with a VA medical center (VAMC). Clinics may be community-based or physically located at a hospital. Recruitment of clinics was initiated by network administrators, who identified outpatient clinics that had little or no academic involvement and that would be appropriate for engagement in the quality improvement implementation project. Leaders at the PC clinic level then agreed to have their clinics participate. Network leaders identified clinics that differed in size and the type of community in which they were located, to capture a greater range of experiences. There was one large clinic in each network; others were small. They were located across five states, including the Southeastern/Gulf Coast, Upper Midwest/Great Lakes, and Northern Great Plains areas of the country. Most were located in metropolitan areas, but three were in small towns in rural areas.

Interviews

We conducted in-depth, semi-structured telephone interviews with ten primary care (PC) and 12 mental health (MH) clinical leaders in these clinics between November 2001 and May 2003. There was at least one of each type of informant from each clinic site. We included clinical leaders from mental health as well as primary care because both have roles in the consultation and referral processes, and each offers slightly different perspective on barriers to depression management in primary care. Informants included 16 physicians, five nurses/nurse practitioners, and one psychologist. Seventeen were male and five were female. There was a wide range in the length of time they had been in their positions (0.25–12.0 years), with an average tenure of 2.6 years. Their average length of time in the VA was 8.9 years (range 0.5–23.8 years).

We designed the interviews to elicit thorough descriptions of the usual processes for detection and management of depression within the clinics. The interview guide was structured to cover the categories of care addressed by clinical guidelines for depression in primary care (Schulberg et al. 1998; VHA/DOD 2000). It included five main topics: (1) current PC depression detection process, (2) current PC depression diagnosis and management practices, (3) current PC–MH referral, consultation, and collaboration practices, (4) barriers to appropriate management of depression within PC, and (5) barriers to PC–MH collaboration. We used a semi-structured framework of 19 questions, which generally moved in order through the care process: screening, diagnosis, treatment, barriers to management in PC, referral process, PC–MH communication, consultations, collaborative activities, and barriers to collaboration. Participants were asked a broadly framed question to elicit description of usual practices, then probed on selected points of interest. We asked follow-up questions to pursue specific aspects that were raised by each informant, and to clarify their beliefs and perceptions on each of the topics. We did not necessarily ask questions in the same order or with the same wording, but followed the participant’s line of thought, while ensuring that we covered all topics in our protocol. In order to discover unanticipated information, we also followed-up relevant topics that were introduced by participants.

For example, regarding existing diagnostic practices, the broad question was, “Do primary care providers at this facility diagnose depression?” Affirmative responses would then be followed with a probe such as, “What type of assessment and diagnosis process would they use?” Then, depending upon the response, there could be a further follow-up for clarification, such as “So, they are doing a diagnosis, but not formally going into the DSM criteria?” Topics that elicited the widest range of responses required the most flexibility in follow-ups. For example, questions about barriers to appropriate PC management of depression would start with a broad question, “Do you think that there are any barriers that impede your facility’s ability to appropriately manage depressed patients that are detected within primary care?” The interviewer would then follow-up on particular responses using questions such as, “Could you tell me more about what you mean by that?” Further probes would include questions such as, “What do you think are the other things that limit their ability to manage it?” “So is that the primary thing?” and “Is there anything else that limits their ability to manage depressed patients as successfully as you’d like?” until the participant indicated that there were no further barriers to depression management. Interviews lasted an average of 60 min each. Professional transcribers produced verbatim transcripts from digital interview recordings.

Administrative Data

We used organization factors, such as clinic size, staffing, and selected structures to provide context for the descriptions of usual care (Table 1). This information was taken from databases that were the closest available to the time period of the interviews: VHA Planning Systems Support Group administrative databases (PSSG), the 1999 national Survey of VHA Primary Care Delivery Systems (Yano 2000), the third quarter 2002 VA Survey of the Health Experiences of Patients (SHEP), and the US Census Bureau classification of metropolitan areas. We counted numbers of total patients for a clinic, and for patients with a diagnosis of depression, by including only those patients who had two or more visits to that clinic during FY 2005, in order to better represent the size of patient population regularly receiving care at that clinic. We identified patients diagnosed as depressed through ICD-9 visit codes entered electronically into medical records by treating clinicians in either primary care or mental health specialty.

Analysis

The interviewers (LP and EY) used a three-stage qualitative content analysis process for the interview data to categorize the responses and describe key processes of care (Crabtree and Miller 1999; Ryan and Bernard 2003). The first interviewer developed a categorization system through review of all the transcripts, and then coded individual responses from each transcript according to the system. Then, the second interviewer independently coded the responses in each transcript using the same system. Finally, the interviewers met and used a mutual consensus process to resolve any coding differences. We examined the coded responses for possible themes and patterns by service type of the respondent (PC or MH) and by site. In this article, we address findings related to descriptions of the usual processes of care. Results from analysis of the descriptions of collaboration between PC and MH have been published previously (Fickel et al. 2007).

We used a matrix method to analyze summary statements of care process and organizational descriptors and synthesize the information into case profiles for each of the primary care practices (Miles and Huberman 1994). One investigator (JF) developed an initial matrix for categorizing statements about the care process and the organizational context factors according to practice site. The values were examined for patterns across cases, and assigned codes according to whether they were common practices and characteristics, or atypical ones. Then, patterns were drawn together within cases, and each case was assessed for the extent of common practices and descriptors, or the presence of outliers. A second investigator (EY) reviewed the matrix for completeness and correctness, and corroborated the coding assignments and case profiles. The two investigators resolved differences in categorization and coding through a mutual consensus process.

Results

Organizational Characteristics of Clinics

The clinics in this study were similar to VA primary care (PC) clinics nationwide in many of the structural characteristics reported in the 1999 national Survey of VHA Primary Care Delivery Systems (Yano 2000), although each one differed on a few traits. The pattern of variation differed for each clinic, which is typical of the clinics nationally. Six of the study clinics had a greater number of internists than family medicine physicians, similar to the national average of eight internists and two family medicine physicians. Four had as many or more family medicine physicians than internists. One clinic was below national average in clerical staff. Seven clinics rated aspects of their staffing and space adequacy worse than the national averages for PC clinics. Four clinics rated aspects of staffing adequacy better than the national averages, and five rated aspects of space adequacy better than the average. Like 89% of VA PC clinics nationally in 1999, all but one of these clinics had a partially or fully implemented quality improvement program. Like 94% of VA PC clinics nationally, PCPs at all ten of these clinics are responsible for assigned patients indefinitely, and most or almost all patients know their assigned PCP (98% nationally). Nationally, patients at 71% of VA PC clinics are almost always seen by their assigned PCP (nine of the clinics in this study), and 29% usually are (one of these clinics). Six of the clinics were at the national VA PC average of 40 min for the length of a new patient visit. Three were shorter than average, at 30 min, and one longer, at 60 min. Three of these clinics exceeded the national average for 22 min. length of a follow-up visit, and one was shorter. Four of these clinics were not significantly different from the national average on nine of the 13 scaled items of the third-quarter, fiscal year 2002 VA national patient satisfaction (SHEP) survey; five performed significantly better than average. No patterns were noted in the variations between clinics in these organizational characteristics when compared with care processes for PC management of depression. Therefore, this structural information is only used descriptively in the present analysis.

Descriptions of Usual Care

Although clinic leaders described particular processes specific to each clinic, many care processes were generally similar across the practices in this study. Leaders at all ten clinics described similarities in main steps of their clinics’ usual processes for identifying and managing depression in primary care patients, including screening, diagnosis, treatment, and consultation and referral (Table 2).

All of the clinics were screening for depression routinely, although the specific method for doing so differed somewhat among clinics. Clinics usually screened new patients and conducted annual screening for existing patients. Typically, a nurse would use an automatic screening reminder with two questions. At the time of the interviews, all clinics but one (A1a) had implemented the VA’s computerized patient record system (CPRS). However, this site was moving from patient self-administered screening to nursing screening, and anticipated being computerized within a month. Leaders mentioned that nurses and PCPs would also screen patients for depression informally on an as-needed basis. Also, although nurses conducted the screening in most clinics, in one clinic (C1b) the PCP would do the screening in the clinical encounter. In another (C2a), the nurse would do an initial automated screening, which the PCP would follow with a second set of automated assessment questions, in the event of a positive screen. This CPRS-based screening and assessment tool also included automatic check boxes for the PCP’s choices of medications, MH referral, and PC follow-up options. In all clinics, positive screens were called to the attention of the PCP, either with the CPRS nurses’ note or a paper routing note.

Leaders from all clinics were brief in their descriptions of assessment and diagnosis for depression, even though we probed for formality of methods that they might use. They indicated that PCPs did diagnose depression, although only rarely in three of the clinics. PCPs used informal diagnostic methods, that is, not necessarily following DSM criteria, and relied to some extent on the screening tools and questions.

Primary care providers usually offered pharmacological treatment for depression in six of the clinics, and sometimes supportive counseling as well. Descriptions of treatment plan development focused primarily on whether to treat in primary care or refer to mental health. The locus of care was determined by PCP comfort level plus the patient’s severity or level of complexity. Patient preference was also a factor in half of the clinics. Leaders rated PCP comfort level with depression care at least moderate, and mostly moderately high or high. In eight clinics, they reported that comfort level varied among individual PCPs. If patients refused referral to MH, PCPs would manage them in primary care. In six of the clinics, they would also try to convince a patient to accept the referral, and/or to reduce the stigma of MH care.

In all nine clinics that had CPRS, PCPs made referrals to MH using the electronic consult system in combination with paper or telephone consults. For urgent evaluation requests, seven clinics used a combination of methods, especially telephoning MH to request an appointment for the patient. Five also walked the patient to the MH clinic. In all the clinics, MHPs provided feedback to the referring PCP via a progress note in the medical record.

Exceptions

Although there were many similarities in the care processes in these clinics, the processes varied substantially on several key points in terms of specific depression management activities. These variations occurred in each step of the care process, and were spread across different clinics, demonstrating a good deal of individuality among sites in the specifics of the care process (Table 2). One clinic (A1a) had variations in four steps of the care process, more than any other clinic. This was due in part to that clinic not yet having implemented the electronic medical record, in addition to historic practice patterns and culture. Two clinics (B1c and C1a) varied in two steps, rarely diagnosing and treating depression in PC. Another clinic (B1b) rarely treated depression, their only exception to the general process of care. Three other clinics, A3a, A4a, and B1a, varied in their processes for urgent referrals to MH. Finally, three clinics, A3b, C1b, and C2a, all followed the general processes of care described by the leaders we interviewed.

The major exceptions to the process of care described for most clinics were in the areas of diagnosis and treatment. Although PCPs in most clinics were diagnosing (seven clinics) and treating (six clinics) depression according to patient severity and PCP comfort levels, there were three clinics (A1a, B1c, C1a) where PCPs rarely diagnosed or treated depression, and a fourth where it was diagnosed but rarely treated (B1b). PCPs in these clinics would generally refer depressed patients to MH, and in clinic C1a, MH referrals were required for patients with positive depression screens, although PCPs had recently begun doing some pharmacological treatment.

Variations also occurred in the usual practices for the referral or consultation process. Although most clinics used the electronic consult as their primary method, the one clinic (A1a) that was not yet computerized walked patients to MH as the usual process for both routine and urgent referrals. There was great variation in the process for urgent MH evaluation requests. Three clinics (A3a, B1a, A4a) mentioned only one method of contacting MH for urgent requests, in contrast to the combination of methods described for most clinics.

Two Illustrative Cases

The A3b community based clinic provides a good example of the typical care process described by the clinical leaders in this study. They are a small clinic, located in a rural area, with approximately 3,800 total patients (individuals with two or more visits to that clinic in fiscal year 2005). According to the 1999 VA Survey of primary care (PC) clinic characteristics, they had about 13 providers, one administrator, 10 clerical staff, and no residents. They differed from the profile of PC clinics nationally in having more family medicine physicians than internists. Most aspects of their staffing levels and their space were rated as barely adequate, or sometimes adequate, at best—worse than the national averages for PC clinics. Like 38% of clinics nationally in 1999, they had a partially implemented quality improvement program in PC, and resources that had not changed notably in the previous year. PCPs were responsible for their assigned patients indefinitely, and patients knew their assigned PCP and were almost always seen by that PCP at scheduled visits. PCPs were allotted 60 min for new patient visits and 30 min for follow-up visits, greater than the national averages of 40 and 22 min, respectively. They performed significantly worse than national average on nine of the 13 scaled items of the third-quarter, fiscal year 2002 national patient satisfaction (SHEP) survey.

The general steps in their usual care process were consistent with those described at the other clinics. Nurses screened patients for depression at least annually, and maybe at every visit. They used a two-question screener that was part of the routine preventive medicine screen. Positive screens were called to the attention of the PCP. PCPs did diagnose depression, although it was unclear whether they used an informal method or a formal one, based on DSM criteria. PCPs treated depression pharmacologically. The decision whether to treat a patient in primary care or refer to mental health was based on individual provider comfort level, the patient’s severity or level of complexity, and the patient’s preference. The PC leader reported that PCP comfort with treating depression was moderately high, and did not vary much among the PCPs. Patients were usually referred to MH using an electronic medical record consult, and also telephone consult requests. For urgent MH evaluation requests, they would indicate “urgent” on the electronic consult request, phone MH and request a same-day appointment, or contact an on-call MH provider. A MH provider gave feedback to a PCP about the services provided to the patient using an unflagged chart note, and also phone calls for urgent information. They reported no problems with PCPs gaining access to MH medical record notes.

Another clinic provides an example of some of the reported usual care practices that varied from the steps generally reported at the clinics. Community based clinic A1a is also a small clinic, with approximately 4,900 total patients. It is located organizationally within the same Integrated Service Network as the A3b Clinic, but in a metropolitan area in geographically distant region, and associated with a different VAMC. The 1999 VA Survey of primary care (PC) clinic characteristics indicated that they had about nine providers, two administrators, eight clerical staff, and no residents. Like Clinic A3b, they differed from the national profile in having more family medicine physicians than internists. They were rated worse than the national average on staffing sufficiency of physicians, administrators, and clerical staff, but better on sufficiency of nursing staff and office space. Like 51% of clinics nationally at that time, they had a fully implemented quality improvement program in PC, and, like many, resources that had not changed notably in the previous year. PCPs were responsible for their assigned patients indefinitely, and patients knew their assigned PCP and were almost always seen by that PCP at scheduled visits. PCPs were allotted 30 min for new patient visits, below the national average of 40, and 30 min for follow-up visits, greater than the national average of 22 min. They performed no differently than the national average on the 13 scaled items of the SHEP patient satisfaction survey.

The general steps in their usual care process differed in several ways from those described at the other clinics. Some of these differences were due to their not yet having a computerized patient record system. They had been using a patient self-administered screening at each visit, and were just moving to a nursing-administered screen. The screening form addressed multiple health issues, and included two items relevant to depression. Like other clinics they flagged positive screens for the PCP, but used a paper process. PCPs here rarely diagnosed depression, and they reported little treatment of depression in PC. When PCPs did treat depression, they used pharmacological methods. Most PCPs did not treat depression due to a culture and history of referring these patients to MH. They also based the decision whether to treat a patient in primary care or refer to MH on PCP comfort level, provider training and experience, and PCPs’ perceived workload. The leaders reported that PCP comfort with treating depression was moderately high, and varied among the PCPs according to their level of experience. Patients were usually referred to MH with telephone consult requests. For urgent MH evaluation requests, they would phone MH and request a same-day appointment, or walk the patient to the MH clinic, or a MH provider would come to the PC clinic. A MH provider gave feedback to a PCP about the services provided to the patient by using a flagged chart note, and also phone calls for urgent information. They also reported no problems with PCPs gaining access to MH medical record notes.

Differences Between Usual Care and Evidence-Based Guidelines

The usual processes of care conformed in part to those of relevant clinical practice guidelines (Schulberg et al. 1998; VHA/DOD 2000), although they differed in that PCPs often used more informal means than delineated by guidelines, and that leaders we interviewed made little mention of activities related to several care process steps in the guidelines. Please see Table 2 for a summarized comparison between guideline recommendations and the usual care for depression described at the study’s clinics.

Processes for routine screening in PC visits for detection of possible depression were occurring at all ten clinics, consistent with guideline recommendations, and all but one clinical leader described how their PC clinics conducted screening. Processes for further clinical assessment and diagnosis of depression, however, were less clear. There was some mention of medical assessment relevant to depression. Leaders from five clinics indicated that PCPs may do some limited assessment of signs and symptoms that may lead to a diagnosis of depression, but that it was rare. Similarly, informants indicated that diagnosis of depression, if made, was done informally. Often it appeared to be a provisional diagnosis based on the positive screening result.

Discussion related to treatment planning centered on the decision of whether a patient would be treated in PC or referred to MH. Although we did not probe about treatment planning, informants from four clinics described PCP assessment and treatment planning as brief and informal. One interviewee described a more formal assessment and treatment planning process, and mentioned involving the patient in treatment planning. Other informants made no mention of treatment planning per se. Informants discussed the process for referrals to MH in depth. Four PC teams referred patients with positive depression screens to MH whenever possible, particularly complex or severe cases. However, all clinics would manage a patient with depression in primary care if the patient refused a referral to MH.

Therapeutic options, in cases where depression was managed in PC, were mostly limited to pharmacotherapy, although informal supportive counseling was also mentioned in four clinics as an adjunct method. A number of factors shaped treatment decisions, including PCP comfort level with treating depression, patient severity or complexity, patient preference, PCP training and experience, and the generally short periods of time available for PCPs to provide care. In addition, the choice of antidepressants available for PCPs to prescribe was also constrained by institutional formularies. Although guidelines mention psychotherapy as efficacious in PC settings, the usual care processes of the clinics in this study were to refer patients desiring psychotherapy to MH, due to lack of qualified providers in PC and time constraints on appointment slots.

Beyond initiating pharmacotherapy, informants from two clinics described care processes related to follow-up monitoring, or the continuation or maintenance phases of treatment. The interviews did not explicitly probe about monitoring, continuation, or maintenance, and only one informant described communication with MH providers in those terms. The other indicated that length of follow-up in PC was up to individual providers, before referring to MH because of inadequate response to treatment. All the leaders, however, described friendly and collegial interactions between PC and MH providers for informal consultations on an as-needed basis. They described various examples of PC–MH consultations and treatment support for patients with positive depression screens, with depression, or with other mental health concerns.

There were even greater differences between the local variant practices and the evidence-based guidelines in the clinics that had notable variations from the general process of care in parts of their processes. The variations, as described above and in Table 2, that presented the greatest departures from guideline recommendations were the rare diagnosis of depression by PCPs, little or no treatment of depression by PCPs, and having minimal procedures in place for urgent MH evaluation requests.

Barriers to PC Depression Care

We also asked clinical leaders in this study about their experiences and perceptions of barriers to appropriate management of patients with depression in PC. Most informants described one or more particular barriers to depression management (Table 3). The two barriers mentioned most often were inadequate time and number of PCPs (mentioned by leaders at six clinics), and inadequate MH training for PC providers (at five). Other barriers mentioned were problematic electronic medical record and poor access to mental health, mentioned at four clinics each. PC provider disinterest, discomfort, or unfamiliarity with depression was mentioned as a barrier at three clinics. Two mentioned patient reluctance due to stigma. Five barriers were mentioned at only one clinic each: poor PCP referral to MH, inadequate MH follow-up, physical distance between PC and MH clinics, institutional policy barriers, and local culture or turf issues. Leaders of two clinics identified no barriers to PC care of depression. The greatest number of barriers mentioned at any clinic was six. No patterns were noted between the number or type of barriers identified by leaders and the number or type of exceptions to the general processes of care for their clinics.

Discussion

In summary, the results from this study reveal a portrait of the usual process of care for depression in ten different primary care practices. We found general similarity across the clinics in methods of screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Yet, clinical leaders also described substantial individuality at the site level. We found the greatest concordance to recommended guidelines for management of depression in primary care settings around screening for depression, for which there were routine processes in place at all ten clinics. We found the greatest differences around further assessment of patients suspected of having depression, formal diagnosis and treatment planning, involving patients in treatment planning, and formal monitoring during follow-up.

The individuality of the ten primary care clinics in this study in their usual processes of depression care demonstrates that “usual care” is not a cleanly defined, uniform protocol, and can exist in various degrees of difference from standard guidelines. It also suggests that adherence to practice guidelines could be viewed more as a continuum than an all-or-nothing situation. This variation among clinics in their usual care would be important to bear in mind, for both intervention and control groups, when interpreting the findings of randomized studies of quality improvement interventions. Moreover, the juxtaposition of differences from guidelines with the various reported barriers to appropriate care for each clinic (Table 3) suggests that that individual practices will have specific needs for targeting quality improvement activities and tailoring interventions to local context.

While this study is most applicable to VA and other staff-model managed care settings (Meredith, et al. 1999), our findings have similar implications to those from non-VA settings. For example, we found that antidepressants were the main or only treatment modality reported by the clinical leaders. Solberg et al. (2005) found that patients in a non-VA medical group practice who had received a new diagnosis of depression from a PCP were usually started on antidepressants as their only therapy, with little patient education or self-management information and few follow-up visits. Hepner et al. (2007) found that PCPs adhered to guidelines to a high degree in detecting and initiating treatment, but to a lower degree in further assessment of symptoms, adjustment of treatment, and follow-up to assure treatment completion. Upshur (2005) similarly reported on usual care described by Medicaid managed care PCPs, who reported using informal methods of assessment and diagnosis, with mostly pharmaceutical treatment, plus supportive visits, and referral to MH. Additionally, they noted the rarity of links between PC and MH.

The greatest conformity with clinical guidelines was in the area of screening. This aspect of primary care depression care has received the greatest emphasis by the Veterans’ Health Administration (VHA) as a whole, and the most organizational support for implementation and integration into routine care. Screening for depression is one section of the VHA prevention index, a mandatory annual screening tool for all PC patients, instituted nationally in 1998 (Kirchner et al. 2004). A recent report of a quality improvement trial that included both VA and Kaiser Permanente practices illustrated the VA’s emphasis on case finding and screening, while Kaiser addressed physician and patient knowledge about depression, and increasing treatment rates (Rubenstein et al. 2006).

The processes of assessment, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up all contained room for improved concordance with guidelines, and are of concern. For example, informal methods of assessment following a positive screen for depression could result in inability to track symptom severity, or non-detection of suicidal threat. In some clinics, PCPs rarely treated depressed patients themselves, relying on referral to mental health specialty. This strategy can lead to gaps in treatment due to low mental health specialist availability and to patient resistance to referral. Depression care improvement relies on increasing treatment within primary care, and targeted collaboration with mental health specialists (Gilbody et al. 2003). The apparent informality of diagnostic techniques, treatment planning, lack of indication of patient involvement in planning, and limited options for treatment modalities may be connected to reported barriers, deriving from the need for more PCP support through training, resources, or both. These same barriers could also be related to the uncertain processes for monitoring, and for continuation and maintenance phases of treatment.

Assessing processes of care at the practice level is important because evidence indicates that quality of care improvement for depression requires changes in care delivery at clinic or practice group level (Gilbody et al. 2006), as in Wagner et al.’s (2001) chronic care model. Evaluation of quality of care, however, has traditionally looked at the individual patient or provider level (Fisher et al. 2006). Lack of attention to the clinic level, however, can miss important aspects of organization structures and relationships that can influence success of practice-level interventions and, ultimately, the quality of care (Grol et al. 2007).

The variation noted among clinics in our study, especially the variation in the degree of concordance with evidence-based practice guidelines, is not surprising. Other reports have indicated that local context is a key factor in interventions related to primary care management of depression. Blaskinsky et al. (2006), observed considerable variation across IMPACT collaborative care intervention sites in operationalization and continuation strategies, and in the barriers and facilitators to sustaining the model. Rollman et al. (2006) described two case studies from RWJ’s Depression in PC Initiative, in which wide variation in organizational context influenced the implementation of the intervention model, and how each health care system customized the clinical model for local relevance. Hysong et al. (2007), compared VA primary care clinics on their performance in implementing clinical practice guidelines, and found differences between high- and low-performing facilities in their investment in and local adaptation of the electronic medical record and other resources dedicated to the initiatives.

The individuality of clinics found in the present study with respect to distance from guidelines and in patterns of barriers suggests that clinic-based approaches to implementing process improvements could be appropriate. For example, one clinic (C2a) was closest to the guidelines. They were not only screening for depression regularly, they had a CPRS-based process in place for limited assessment, assigned an informal provisional diagnosis and did limited treatment planning, offered informal supportive counseling in addition to pharmaceutical treatment, followed-up to check for improved symptoms and adjust treatment if needed, and communicated with MH for continuation and maintenance decisions. Clinical leaders here reported three barriers to PC depression care: an inadequate number of PCPs and too little time, inadequate PCP training on depression, and patient preference other than treatment in PC. Increasing the ability of PCPs to do formal assessment and diagnosis and making other treatment modalities available in PC would improve coherence with guidelines. A multi-faceted, evidence-based strategy, such as collaborative care, could help address these barriers through utilization of a depression care manager or co-located MH provider, as well as increasing knowledge about depression.

On the other hand, the three clinics where PCPs rarely diagnose or treat depression (A1a, B1c, and C1a) were most distant from the guidelines. Each clinic, however, had a different profile of barriers. For example, clinic A1a not only reported the common barrier of inadequate PCP time and numbers, but also described a situation that included barriers related to institutional policy within the clinic and healthcare system, plus a legacy of local culture and turf issues. Attempts at implementing collaborative care, including adding a depression care manager or co-located MH provider to this clinic, without addressing the greater systemic issues with policy and culture, would be unlikely to move the practice a great deal closer to the guideline recommendations.

Another situation might require a still different quality improvement approach. Two clinics (B1b and C1b) reported no barriers to appropriate PC management of patients with depression, yet had a number of variations from guideline-concordant practice. Such clinics may lack awareness of the need for change (Pathman et al. 1996), and need further assessment, education on practice guidelines, or other pre-intervention actions to better understand the appropriate strategy for tailoring an intervention to improve guideline concordance.

Tension exists between the potential benefits of allowing local autonomy in adapting care models and guidelines, versus the benefits of disseminating standardized, evidenced-based models (Litaker et al. 2006). Although standardization has advantages of greater confidence in fidelity to the evidence basis and efficiency in dissemination, there is the disadvantage that the standardized model may go unused because it does not specifically address problems as perceived by local stakeholders. On the other hand, adaptation to the individuality of local situations can improve buy-in and implementation of changes, but there is the risk of adapting away the effective parts of the evidence-based model. Previous qualitative work suggests that a combination of central guidance for local-level stakeholders in tailoring a collaborative care model to local needs may provide the optimal balance (Parker et al. 2007; Rubenstein et al. 2006).

This study has limitations. First, informants were limited to clinical leaders, whose perceptions may not necessarily represent the viewpoints of all providers in each clinic. However, they were all practicing clinicians as well as administrators, and that dual perspective should enable them to be adequate representatives of their sites. Also, time constraints precluded follow-up on all possible specific aspects of care processes in each interview. In addition, these sites were chosen for participation because their network and clinical leaders had an expressed interest in improving their PC care for depression. The sites themselves did not volunteer, although they agreed to participate. Therefore, these clinical leaders may be less aware of PC depression care issues than leaders from volunteer clinics would have been. Overall, we spoke with informants at only 10 VA clinics. Although geographically diverse and relatively large for a qualitative study, these cases do not represent all PC clinics, either within or outside the VA system, and specific findings may not be generalizable. We show, however, that the basic characteristics of these clinics are similar to national VA averages. VA PC clinician attitudes and practices have also been shown to be similar to those of clinicians in non-VA staff/group model organizations (Meredith et al. 1999). Our basic findings regarding the need to consider variations in usual care should extrapolate to other settings. Finally, it should be noted that the VA is in the process of updating the guidelines for treatment of depression in primary care. We anticipate that the updated guidelines will incorporate greater detail on the process of care steps that we have discussed in this article, and that our findings and recommendations will remain relevant.

In conclusion, we found substantial, site-specific individuality in usual care for depression and in barriers to appropriate care across VA primary care clinics. Researchers and quality improvement leaders should assume that such variations are present, and consider how best to respond to such differences. Rather than treating usual care as a black box, they could take account of this usual care information in analysis. For example, pre-implementation assessment of usual care might include clinic-level care processes, variations from clinical practice guidelines, and barriers to adherence, in addition to basic organizational factors such as staffing levels, training, information technology capabilities, and institutional policies and procedures. This information could be used to provide a clinic-specific baseline for rigorous evaluation designs of quality improvement interventions, and could also help tailor implementations of models such as collaborative care for depression. Further work should examine whether and how evidence-based models have been adapted for local situations, fidelity of implementation across sites, and linkages between fidelity of processes and care outcomes.

References

Blaskinsky, M., Goldman, H. H., & Unutzer, J. (2006). Project IMPACT: A report on barriers and facilitators to sustainability. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 33, 718–729. doi:10.1007/s10488-006-0086-7.

Bruce, M. L., Ten Have, T. R., Reynolds, C. F., Katz, I. I., Schulberg, H. C., Mulsant, B. H., et al. (2004). Reducing suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 291(9), 1081–1091. doi:10.1001/jama.291.9.1081.

Crabtree, B. F., & Miller, W. L. (1999). Using codes and code manuals. In B. F. Crabtree & W. L. Miller (Eds.), Doing qualitative research (2nd ed.). Sage: Thousand Oaks.

Fickel, J. J., Parker, L. E., Yano, E. M., & Kirchner, J. E. (2007). Primary care-mental health collaboration: An example of assessing usual practice and potential barriers. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 21, 207–216. doi:10.1080/13561820601132827.

Fisher, E. S., Staiger, D. O., Bynum, J. P. W., & Gottlieb, D. J. (2006). Creating accountable care organizations: The extended hospital medical staff. Health Affairs, 26(1), w44–w57. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.26.1.w44.

Gilbody, S., Whitty, P., Grimshaw, J., & Thomas, R. (2003). Educational and organizational interventions to improve the management of depression in primary care. Journal of the American Medical Association, 289(23), 3145–3151. doi:10.1001/jama.289.23.3145.

Gilbody, S., Bower, P., Fletcher, J., Richards, D., & Sutton, A. J. (2006). Collaborative care for depression: A cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166, 2314–2321. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.21.2314.

Grol, R. P. T. M., Bosch, M. C., Hulscher, M. E. J. L., Eccles, M. P., & Wensing, M. (2007). Planning and studying improvement in patient care: The use of theoretical perspectives. The Milbank Quarterly, 85(1), 93–138. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00478.x.

Hepner, K. A., Rowe, M., Rost, K., Hickey, S. C., Sherbourne, C. D., Ford, D. E., et al. (2007). The effect of adherence to practice guidelines on depression outcomes. Annals of Internal Medicine, 147, 320–329.

Hysong, S. J., Best, R. G., & Pugh, J. A. (2007). Clinical practice guideline implementation strategy patterns in Veterans Affairs primary care clinics. Health Services Research, 42(1), 84–103. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00610.x.

Joo, J. H., Solano, F. X., Mulsant, B. H., Reynolds, C. F., & Lenze, E. J. (2005). Predictors of adequacy of depression management in the primary care setting. Psychiatric Services (Washington, DC), 56(12), 1524–1528. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.56.12.1524.

Kilbourne, A. M., Schulberg, H. C., Post, E. P., Rollman, B. L., Belnap, B. H., & Pincus, H. A. (2004). Translating evidence-based depression management services to community-based primary care practices. The Milbank Quarterly, 82(4), 631–659. doi:10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00326.x.

Kirchner, J. E., Curran, G. M., & Aikens, J. (2004). Detecting depression in VA primary care clinics. Psychiatric Services (Washington, DC), 55(4), 350. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.55.4.350.

Lin, E. H. B., Katon, W., Rutter, C., Simon, G. E., Ludman, E. J., Von Korff, M., et al. (2006). Effects of enhanced depression treatment on diabetes self-care. Annals of Family Medicine, 4(1), 46–53. doi:10.1370/afm.423.

Litaker, D., Tomolo, A., Liberatore, V., Stange, K. C., & Aron, D. (2006). Using complexity theory to build interventions that improve health care delivery in primary care. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21, S30–S34. doi:10.1007/s11606-006-0272-z.

Liu, C. F., Campbell, D. G., Chaney, E. F., Li, Y. F., McDonnell, M., & Fihn, S. D. (2006). Depression diagnosis and antidepressant treatment among depressed VA primary care patients. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 33, 331–341. doi:10.1007/s10488-006-0043-5.

Meredith, L. S., Rubenstein, L. V., Rost, K., Ford, D. E., Gordon, N., Nutting, P., et al. (1999). Treating depression in staff-model versus network-model managed care organizations. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 14, 39–48. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00279.x.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis (2nd ed.). Sage: Thousand Oaks.

Nutting, P. A., Rost, K., Dickinson, M., Werner, J. J., Dickinson, P., Smith, J. L., et al. (2002). Barriers to initiating depression treatment in primary care practice. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 17, 103–111. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10128.x.

Oxman, T. E., Dietrich, A. J., Williams, J. W., & Kroenke, K. (2002). A three-component model for reengineering systems for the treatment of depression in primary care. Psychosomatics, 43(6), 441–450. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.43.6.441.

Parker, L. E., de Pillis, E., Altschuler, A., Rubenstein, L. V., & Meredith, L. S. (2007). Balancing participation and expertise: A comparison of locally and centrally managed health care quality improvement within primary care practices. Qualitative Health Research, 17(9), 1268–1279. doi:10.1177/1049732307307447.

Pathman, D. E., Konrad, T. R., Freed, G. L., Freeman, V. A., & Koch, G. G. (1996). The awareness-to-adherence model of the steps to clinical guideline compliance. The case of pediatric vaccine recommendations. Medical Care, 34(9), 873–889. doi:10.1097/00005650-199609000-00002.

Pincus, H. A., Hough, L., Houtsinger, J. K., Rollman, B. L., & Frank, R. G. (2003). Emerging models of depression care: Multi-level (‘6P’) strategies. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 12(1), 54–63. doi:10.1002/mpr.142.

Robinson, W. D., Geske, J. A., Prest, L. A., & Barnacle, R. (2005). Depression treatment in primary care. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 18(2), 79–86.

Rollman, B. L., Weinreb, L., Korsen, N., & Schulberg, H. C. (2006). Implementation of guideline-based care for depression in primary care. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 33(1), 43–53. doi:10.1007/s10488-005-4235-1.

Rubenstein, L. V., Jackson-Triche, M., Unutzer, J., Miranda, J., Minnium, K., Pearson, M. L., et al. (1999). Evidence-based care for depression in managed primary care practices. Health Affairs, 18(5), 89–105. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.18.5.89.

Rubenstein, L. V., Meredith, L. S., Parker, L. E., Gordon, N. P., Hickey, S. C., Oken, C., et al. (2006). Impacts of evidence-based quality improvement on depression in primary care. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21, 1027–1035. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00549.x.

Ryan, G. W., & Bernard, H. R. (2003). Data management and analysis methods. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Collecting and interpreting qualitative materials (2nd ed.). Sage: Thousand Oaks.

Schulberg, H. C., Katon, W., Simon, G. E., & Rush, A. J. (1998). Treating major depression in primary care practice: An update of the agency for health care policy and research practice guidelines. Archives of General Psychiatry, 55, 1121–1127. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.55.12.1121.

Solberg, L. I., Trangle, M. A., & Wineman, A. P. (2005). Follow-up and follow-through of depressed patients in primary care: The critical missing components of quality care. The Journal of the American Board of Family Practice, 18, 520–527.

Stake, R. E. (2003). Case studies. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Strategies of qualitative inquiry (2nd ed.). Sage: Thousand Oaks.

Stroebel, C. K., McDaniel, R. R., Crabtree, B. F., Miller, W. L., Nutting, P. A., & Stange, K. C. (2005). How complexity science can inform a reflective process for improvement in primary care practices. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 31(8), 438–446.

Unutzer, J., Katon, W., Williams, J. W., Callahan, C. M., Harpole, L., Hunkeler, E., et al. (2001). Improving primary care for depression in late life: The design of a multicenter randomized trial. Medical Care, 39(8), 785–799. doi:10.1097/00005650-200108000-00005.

Upshur, C. C. (2005). Crossing the divide: Primary care and mental health integration. Administration and Policy In Mental Health, 32(4), 341–355. doi:10.1007/s10488-004-1663-2.

Veterans Health Administration and Department of Defense. (2000). VHA/DOD clinical practice guideline for the management of major depressive disorder in adults, version 2.0.

Wagner, E. H., Austin, B. T., Davis, C., Hindmarsh, M., Schaefer, J., & Bonomi, A. (2001). Improving chronic illness care: Translating evidence into action. Health Affairs, 20(6), 64–78. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64.

Wells, K. B., Schoenbaum, M., Unutze, J., Laomasino, I. T., & Rubenstein, L. V. (1999). Quality of care for primary care patients with depression in managed care. Archives of Family Medicine, 8(6), 529–536. doi:10.1001/archfami.8.6.529.

Williams, J. W., Gerrity, M., Holsinger, T., Dobscha, S., Gaynes, B., & Dietrich, A. (2007). Systematic review of multifaceted interventions to improve depression care. General Hospital Psychiatry, 29, 91–116. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.12.003.

Yano, E. M. (2000). Managed care performance of VHA primary care delivery systems. Final report for VA HSR&D Project #MPC-970121.

Young, A. S., Klap, R., Sherbourne, C. D., & Wells, K. B. (2001). The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry, 58, 55–61. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.58.1.55.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Veterans Administration Health Services Research and Development Funded Studies MHT 01-027 and MNT 02-029, and an Associate Investigator Award. The authors would like to thank the VA clinical leaders who represented their clinics for this study, and the anonymous reviewers for their comments on the manuscript.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Fickel, J.J., Yano, E.M., Parker, L.E. et al. Clinic-Level Process of Care for Depression in Primary Care Settings. Adm Policy Ment Health 36, 144–158 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-009-0207-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-009-0207-1