Abstract

Let \(\mathscr {C}\) be a 2-Calabi–Yau triangulated category with two cluster tilting subcategories \(\mathscr {T}\) and \(\mathscr {U}\). A result from Jørgensen and Yakimov (Sel Math (NS) 26:71–90, 2020) and Demonet et al. (Int Math Res Not 2019:852–892, 2017) known as tropical duality says that the index with respect to \(\mathscr {T}\) provides an isomorphism between the split Grothendieck groups of \(\mathscr {U}\) and \(\mathscr {T}\). We also have the notion of c-vectors, which using tropical duality have been proven to have sign coherence, and to be recoverable as dimension vectors of modules in a module category. The notion of triangulated categories extends to the notion of \((d+2)\)-angulated categories. Using a higher analogue of cluster tilting objects, this paper generalises tropical duality to higher dimensions. This implies that these basic cluster tilting objects have the same number of indecomposable summands. It also proves that under conditions of mutability, c-vectors in the \((d+2)\)-angulated case have sign coherence, and shows formulae for their computation. Finally, it proves that under the condition of mutability, the c-vectors are recoverable as dimension vectors of modules in a module category.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Let \(\mathscr {C}\) be a triangulated category with certain nice properties, and let K be an algebraically closed field. The notion of a cluster tilting subcategory of \(\mathscr {C}\) is due to [4, Definition 2.2], and we can define the index with respect to a cluster tilting subcategory [10, Section 2.1]. The index has several useful properties that aid computation and comparison of cluster tilting subcategories. Thanks to [2, 7], we have an isomorphism which we name tropical duality:

Theorem

(Jørgensen–Yakimov)[7, Theorem 1.2] [2, Cor. 6.20] Suppose that \(\mathscr {C}\) is 2-Calabi–Yau , K-linear, Hom-finite and Krull–Schmidt. For every pair of cluster tilting subcategories \(\mathscr {T}\) and \(\mathscr {U}\), there are inverse isomorphisms

This implies, as shown already by Dehy and Keller [1], that all cluster tilting subcategories of \(\mathscr {C}\) have the same number of indecomposable objects.

We have the notion of homological c-vectors with respect to these objects, as defined in [7, Definition 2.9]. Jørgensen and Yakimov proved in [7, Theorem 1.2(2)] that these c-vectors can be obtained as dimension vectors in the module category of the endomorphism ring of a cluster tilting object, which generalises work done by Chávez [8].

In this paper we will generalise these results into the higher homological case. We recall some important definitions before stating these results. Instrumental to everything we do here are the notions of Oppermann–Thomas cluster tilting subcategory and index. These definitions require a \((d+2)\)-angulated category as defined by Geiss et al. [3]. We will recap this in Sect. 2. For the following definitions, we let ( ) be a \((d+2)\)-angulated category.

) be a \((d+2)\)-angulated category.

Definition 1.1

[9, Definition 5.3] Let \(\mathscr {C}\) be a \((d+2)\)-angulated category, and let T be an object of \(\mathscr {C}\). Let \(\mathscr {T} = \text {add}(T)\) be the additive subcategory of \(\mathscr {C}\) generated by the indecomposable summands of T. We call \(\mathscr {T}\) an Oppermann–Thomas cluster tilting subcategory of \(\mathscr {C}\) if:

-

(i)

\(\text {Hom}_{\mathscr {C}}{}(\mathscr {T}, \Sigma ^d(\mathscr {T})) = 0\),

-

(ii)

for any \(c \in \mathscr {C}\), there exists a \((d+2)\)-angle

$$\begin{aligned} t_d \rightarrow t_{d-1} \rightarrow \cdots \rightarrow t_1 \rightarrow t_0 \rightarrow c \rightarrow \Sigma ^d(t_d) \end{aligned}$$(1)in \(\mathscr {C}\) where \(t_i \in \mathscr {T}\) for each i.

In this case, T is an Oppermann–Thomas cluster tilting object of \(\mathscr {C}\).

Definition 1.2

If we have an Oppermann–Thomas cluster tilting subcategory \(\mathscr {T} = \text {add}(T)\) we may define the split Grothendieck group for \(\mathscr {T}\), which we denote \(K^{\text {split}}_0{}(\mathscr {T})\). This group is the free abelian group generated by the isomorphism classes [t] of objects \(t \in \mathscr {T}\), modulo all the relations of the form \([t]=[t_0] + [t_1]\) where \(t \cong t_0 \oplus t_1\). This gives us the following formula:

Using Definition 1.2, we may define the notion of index:

Definition 1.3

[6, Definition B] The index of an object \(c \in \mathscr {C}\) with respect to an Oppermann–Thomas cluster tilting subcategory \(\mathscr {T}\) is defined as:

where

is a \((d+2)\)-angle in \(\mathscr {C}\) with each \(t_i \in \mathscr {T}\). It follows from [6, Remark 5.4] that the index is well defined when \(\mathscr {C}\) is Hom-finite with split idempotents.

We introduce some notation that we will use throughout. Let \(\mathscr {C}\) be a \((d+2)\)-angulated category, and let T be an Oppermann–Thomas cluster tilting object with \(\Gamma _T = \text {End}(T)\). Then we can define a functor \(F_T: \mathscr {C} \rightarrow \text {mod }\Gamma _T\) that acts by sending \(x \in \mathscr {C}\) to \(\text {Hom}_{\mathscr {C}}{}(T, x)\).

We pause here to note that unlike in the classic case, there are cluster tilting subcategories in the higher case which are not mutable. We define mutability in the following way:

Let U be a basic Oppermann–Thomas cluster tilting object of \(\mathscr {C}\), and let \(\{u_1, u_2, \ldots , u_m\}\) be the set of indecomposable summands of U. We say that U is mutable at the indecomposable summand \(u \in \{u_1, u_2, \ldots , u_m\}\) if there is an indecomposable object \(u^* \in \mathscr {C}\) such that the object with indecomposable summands \((\{u_1, u_2, \ldots , u_m\} \backslash u) \cup u^*\) is also an Oppermann–Thomas cluster tilting object. In this case we call \(u^*\) a mutation of u. We can then make the following definition.

Definition 1.4

Let \(\mathscr {C}\) be a \((d+2)\)-angulated category, let U be a basic Oppermann–Thomas cluster tilting object with \(\mathscr {U} = \text {add}(U)\). Suppose that U is mutable at u with the mutation \(u^*\). We call u and \(u^*\) an exchange pair if \(\text {Ext}^d(u, u^*)\) and \(\text {Ext}^d(u^*, u)\) both have dimension 1 over K, and there exist two \((d+2)\)-angles

and

in \(\mathscr {C}\) where each \(e_i\) and \(f_i\) is a sum of indecomposable summands from \((\text {Indec}{}(\mathscr {U}) \backslash u)\).

We note at this point that definition 1.4 contains strong assumptions. In Sect. 5 we show a family of examples, defined to be the \((d+2)\)-angulated higher cluster categories of Dynkin type \(A_n\), in which these assumptions are all met and these exchange pairs exist.

We fix some more terminology:

Definition 1.5

We will often consider the following setup: K is an algebraically closed field, and \(\mathscr {C}\) is a 2d-Calabi–Yau \((d+2)\)-angulated category that is K-linear, Hom-finite, and Krull–Schmidt. Let T and U be two basic Oppermann–Thomas cluster tilting objects of \(\mathscr {C}\), with corresponding subcategories \(\mathscr {T} = \text {add}{}(T)\) and \(\mathscr {U} = \text {add}{}(U)\). We let \(\Gamma _T = \text {End}(T)\) and \(\Gamma _U = \text {End}(U)\), and let the functors \(F_T\) and \(F_U\) be defined as above.

Finally, we can define homological c-vectors and g-vectors. For an abelian group A, we set

If T is basic and \(\text {add}{}(T)=\mathscr {T} \subseteq \mathscr {C}\) is an Oppermann–Thomas cluster tilting subcategory, then

where \([t]^* \in K^{\text {split}}_0{}(\mathscr {T})^*\) is the unique element defined by

Definition 1.6

Let \(\mathscr {C}\), T, and U be as in Definition 1.5. For \(u \in \text {Indec}{}(\mathscr {U})\), we define the homological c-vector of \((u, \mathscr {U})\) with respect to \(\mathscr {T}\) to be the element \(c_\mathscr {T}(u,\mathscr {U}){} \in K^{\text {split}}_0{}(\mathscr {T})^*\) such that

By Theorem 3.2 the set \(\{\text {Ind}_\mathscr {T}(v) \, | \, v \in \text {Indec}(\mathscr {U}) \}\) is a basis for \(K^{\text {split}}_0{}(\mathscr {T})\). Therefore the linear map \(c_\mathscr {T}(u,\mathscr {U}){}: K^{\text {split}}_0{}(\mathscr {T}) \rightarrow \mathbb {Z}\) exists and is uniquely determined.

Definition 1.7

Let \(\mathscr {C}\), T, and U be as in Definition 1.5. For \(u \in \text {Indec}{}(\mathscr {U})\), we define the homological g-vector of u with respect to \(\mathscr {T}\) to be the element \(g_\mathscr {T}(u) = \text {Ind}_\mathscr {T}{}(u)\) of \(K_0^{\text {split}}(\mathscr {T})\).

It is common to drop the word “homological” from both Definitions 1.6 and 1.7 and refer to c-vectors and g-vectors, respectively.

If the set \(\{ e_1, e_2, \ldots , e_n \}\) is a basis of the free group A, then the dual basis \(\{\epsilon _1, \epsilon _2 , \ldots , \epsilon _n \}\) of \(A^* := \text {Hom}_\mathbb {Z}(A, \mathbb {Z})\) is defined by \(\epsilon _i(e_j) = \delta _{ij}\). By Theorem 3.2 the g-vectors \(\{g_\mathscr {T}(u) = \text {Ind}_\mathscr {T}(u)| u \in \text {Indec}{}(\mathscr {U}) \}\) are a basis of \(K_0^{\text {split}}(\mathscr {T})\). The c-vectors \(\{c_\mathscr {T}(u,\mathscr {U}){}| u \in \text {Indec}(\mathscr {U}) \}\) are the dual basis of \(K_0^{\text {split}}(\mathscr {T})^*\).

Having made these definitions, we state here the three main results of this paper.

Theorem A

(= Theorem 3.1) Let \(\mathscr {C}\), \(\mathscr {T}\), and \(\mathscr {U}\) be as in Definition 1.5. Then there are inverse isomorphisms

Theorem B

Let \(\mathscr {C}\), \(\mathscr {T}\), and \(\mathscr {U}\) be as in Definition 1.5. Then \(\mathscr {T}\) and \(\mathscr {U}\) have the same number of indecomposable objects.

The above two results will be proven in general; that is, no mutability is required. Finally, we will prove the following:

Theorem C

(=Theorem 4.8, sign coherence for c-vector) Let \(\mathscr {C}\), T, and U be as in Definition 1.5. Suppose that d is odd, and that U is mutable at u with the mutation \(u^*\) such that u and \(u^*\) form an exchange pair. Then either (i) or (ii) below is true.

-

(i)

\(c_\mathscr {T}(u,\mathscr {U})([t]) \ge 0\) for all \(t \in \mathscr {T}\) and

$$\begin{aligned} c_\mathscr {T}(u,\mathscr {U}){}([t]) = \text {dim}_K \text {Hom}_{\Gamma _T}(F_T(t), \text {Im}(\delta _*)) \end{aligned}$$where \(\delta \) is the morphism from u to \(\Sigma ^d u^*\) shown in Eq. (2) and \(\delta _* = F_T(\delta )\).

-

(ii)

\(c_\mathscr {T}(u,\mathscr {U})([t]) \le 0\) for all \(t \in \mathscr {T}\) and

$$\begin{aligned} c_\mathscr {T}(u,\mathscr {U}){}([t]) = -\text {dim}_K\text {Hom}_{\Gamma _T}(F_T(t), \text {Im}(\epsilon _*)) \end{aligned}$$where \(\epsilon \) is the morphism from \(u^*\) to \(\Sigma ^d u\) shown in Eq. (3) and \(\epsilon _* = F_T(\epsilon )\).

Note that if t is an indecomposable summand of T then \(F_T(t)\) is an indecomposable projective \(\Gamma _T\)-module. Hence \(\text {dim}_K\text {Hom}_{\Gamma _T}(F_T(t), M)\) is an entry in the dimension vector of M when \(M \in \text {mod}\Gamma _T\) and Theorem C shows that certain sign coherent c-vectors can be realised as dimension vectors.

2 Definitions

We begin with some definitions. For the purpose of this paper, K is an algebraically closed field. We note also that by \(\text {mod }\Lambda \) we denote the right \(\Lambda \)-modules for a finite dimensional K-algebra \(\Lambda \).

Definition 2.1

[3, Definition 2.1] Let \(\mathscr {C}\) be an additive category with an automorphism \(\Sigma ^d\) for \(d \in \mathbb {Z}, 0<d\). The inverse is denoted \(\Sigma ^{-d}\), but we note that \(\Sigma ^d\) is not assumed to be the d-th power of another functor. Then a \(\Sigma ^d\)-sequence in \(\mathscr {C}\) is a diagram of the form

with each \(c^i \in \mathscr {C}\).

Definition 2.2

[3, Definition 2.1] A \((d+2)\)-angulated category is a triple ( ) where

) where  is a class of \(\Sigma ^d\)-sequences called \((d+2)\)-angles, satisfying the following conditions:

is a class of \(\Sigma ^d\)-sequences called \((d+2)\)-angles, satisfying the following conditions:

-

(N1)

is closed under sums and summands, and contains the \((d+2)\)-angle $$\begin{aligned} c \xrightarrow {id_c} c \rightarrow 0 \rightarrow \cdots \rightarrow 0 \rightarrow 0 \rightarrow \Sigma ^d(c) \end{aligned}$$

is closed under sums and summands, and contains the \((d+2)\)-angle $$\begin{aligned} c \xrightarrow {id_c} c \rightarrow 0 \rightarrow \cdots \rightarrow 0 \rightarrow 0 \rightarrow \Sigma ^d(c) \end{aligned}$$for each \(c \in \mathscr {C}\). For each morphism \(c^0 \xrightarrow {\gamma ^0} c^1\) in \(\mathscr {C}\), the class

contains a \(\Sigma ^d\)-sequence of the form in Definition 2.1.

contains a \(\Sigma ^d\)-sequence of the form in Definition 2.1. -

(N2)

The \(\Sigma ^d\)-sequence (4) is in

if and only if the \(\Sigma ^d\)-sequence $$\begin{aligned} c^1 \xrightarrow {\gamma ^1} c^2 \rightarrow c^3 \rightarrow \cdots \rightarrow c^{d+1} \rightarrow \Sigma ^d(c^0) \xrightarrow {(-1)^d\Sigma ^d(\gamma ^0)} \Sigma ^d(c^1) \end{aligned}$$

if and only if the \(\Sigma ^d\)-sequence $$\begin{aligned} c^1 \xrightarrow {\gamma ^1} c^2 \rightarrow c^3 \rightarrow \cdots \rightarrow c^{d+1} \rightarrow \Sigma ^d(c^0) \xrightarrow {(-1)^d\Sigma ^d(\gamma ^0)} \Sigma ^d(c^1) \end{aligned}$$is in

. This sequence is known as the left rotation of sequence (4).

. This sequence is known as the left rotation of sequence (4). -

(N3)

A commutative diagram with rows in

has the following extension property:

has the following extension property:

That is, given two maps \(\beta _0: b^0 \rightarrow c^0\) and \(\beta _1: b^1 \rightarrow c^1\), there exist maps \(\beta _i:b^i \rightarrow c^i\) for \(2 \le i \le d+1\) such that the diagram above is commutative.

-

(N4)

The Octahedral Axiom, see [3, Definition 2.1].

Definition 2.3

Let \(\mathscr {C}\) be a \((d+2)\)-angulated category, and let \(D=\text {Hom}_K(-, K)\) be the usual duality functor. A Serre functor for \(\mathscr {C}\) is an auto-equivalence \(S: \mathscr {C} \rightarrow \mathscr {C}\) together with a family of isomorphisms which are natural in X and Y

We call the category \(\mathscr {C}\) 2d-Calabi–Yau if \(\mathscr {C}\) admits a Serre functor which is isomorphic to \((\Sigma ^d)^2\), which we often write \(\Sigma ^{2d}\).

We also state here a result that will be instrumental. Recall that if we let \(\mathscr {C}\) be a \((d+2)\)-angulated category, and let T be an Oppermann–Thomas cluster tilting object with \(\Gamma _T = \text {End}(T)\), then we have the functor \(F_T: \mathscr {C} \rightarrow \text {mod }\Gamma _T\) that acts by sending \(x \in \mathscr {C}\) to \(\text {Hom}_{\mathscr {C}}{}(T, x)\). In fact, by [5, Theorem 0.5], we have a commutative diagram

where \(\mathscr {D}\) is d-cluster tilting in \(\text {mod }\Gamma _T\). This means that for \(x, y \in \mathscr {C}\), we have that \(\text {Hom}_{\frac{\mathscr {C}}{[\Sigma ^d \mathscr {T}]}}{}(x, y) \cong \text {Hom}_{\Gamma _T}(F_T(x), F_T(y))\). Here \([\Sigma ^d \mathscr {T}]\) is the ideal of \(\mathscr {C}\) consisting of the morphisms that factor through \(\Sigma ^d \mathscr {T}\).

Using this definition, the result is as follows:

Theorem 2.4

[6, Theorem C] Let \(\mathscr {C}\) be a 2d-Calabi–Yau \((d+2)\)-angulated category that is K-linear, Hom-finite, and Krull–Schmidt. Let T be an Oppermann–Thomas cluster tilting object of \(\mathscr {C}\). Then there is a homomorphism of abelian groups \(\theta : K_0(\text {mod } \Gamma _T) \rightarrow K^{\text {split}}_0{}(\mathscr {T})\) such that for any \((d+2)\)-angle

in \(\mathscr {C}\), we have that

3 Tropical Duality

In this section, we prove the main result of this document. Throughout \(\mathscr {C}\) is a \((d+2)\)-angulated category, and \(\mathscr {T}\) is an Oppermann–Thomas cluster tilting subcategory of \(\mathscr {C}\). Firstly, we would like to extend our definition of index. The split Grothendieck group of \(\mathscr {C}\) can be defined in the same way as for \(\mathscr {T}\), as shown in Definition 1.2. Then we may define a homomorphism

by

for all \(c \in \mathscr {C}\). We also note that the translation functor maps the split Grothendieck group of \(\mathscr {C}\) to itself, in the following way:

We now prove Theorem A, which we restate here:

Theorem 3.1

Let \(\mathscr {C}\), \(\mathscr {T}\), and \(\mathscr {U}\) be as in Definition 1.5. Then there are inverse isomorphisms

Proof

Let \(u \in \mathscr {U}\) be given. By Definition 1.1, there is a \((d+2)\)-angle

in \(\mathscr {C}\) with each \(t_i \in \mathscr {T}\). Then \(\text {Ind}_\mathscr {T}{}([u]) = \Sigma _{i=0}^d (-1)^i[t_i]\), and so

By rotating this \((d+2)\)-angle, we also have the \((d+2)\)-angle

By Theorem 2.4 we have that

The target of \(F_U(\psi )\) is \(\text {Hom}_\mathscr {C}(U, \Sigma ^d u).\) As \(u \in \mathscr {U}\), by Definition 1.1 (i), \(\text {Hom}_\mathscr {C}(U, \Sigma ^d u) = 0\) so \(F_U(\psi ) = 0\). We obtain that

which gives us that

as \((-1)^{d+2} = (-1)^d\). We have shown that

Proceeding in a similar fashion, let \(t \in \mathscr {T}\) be given. Again by definition we have a \((d+2)\)-angle

in \(\mathscr {C}\) with each \(u_i \in \mathscr {U}\). Then we have the \((d+2)\)-angle

The first \((d+2)\)-angle gives us that

and the second gives us that

by Theorem 2.4. This means that

Written another way this is

as required. \(\square \)

We see that Theorem B follows immediately from Theorem 3.1. We also have the following immediate consequence of Theorem 3.1:

Theorem 3.2

Let \(\mathscr {C}\), \(\mathscr {T}\), and \(\mathscr {U}\) be as in Definition 1.5. Then

Proof

As \(K^{\text {split}}_0{}(\mathscr {T})\) and \(K^{\text {split}}_0{}(\mathscr {U})\) are isomorphic, a basis of \(K^{\text {split}}_0{}(\mathscr {U})\) becomes a basis of \(K^{\text {split}}_0{}(\mathscr {T})\) under the action of the isomorphism. \(\square \)

4 c-Vectors and the Proof of Theorem C

4.1 Computing c-Vectors Using Tropical Duality

We may use Theorem 3.1 to show two formulae for the computation of c-vectors.

Theorem 4.1

Let \(\mathscr {C}\), \(\mathscr {T}\), and \(\mathscr {U}\) be as in Definition 1.5. Then the c-vector of the pair \((u, \mathscr {U})\) with respect to the Oppermann–Thomas cluster tilting subcategory \(\mathscr {T}\) is given by

Proof

Let \(v \in \text {Indec}{}(\mathscr {U})\) be given. Then

\(\square \)

Lemma 4.2

Let \(\mathscr {C}\), T, and U be as in Definition 1.5. Suppose that U is mutable at u with the mutation \(u^*\) such that u and \(u^*\) form an exchange pair. Then \(F_U(\Sigma ^d u^*)\) is simple in the abelian category \(\text {mod }\Gamma _U\).

Proof

We have

by Definition 1.1(i). By the assumption that u and \(u^*\) form an exchange pair, the space \(\text {Hom}_{\mathscr {C}}{}(u, \Sigma ^d u^*)\) is one dimensional. This means that in \(\text {mod }\Gamma _U\), the object \(\text {Hom}_{\mathscr {C}}{}(U, \Sigma ^d u^*) = F_U(x)\) is one dimensional. This gives us the simplicity of the object.

We may immediately use this simplicity to prove another lemma:

Lemma 4.3

Let \(\mathscr {C}\), T, and U be as in Definition 1.5. Suppose that U is mutable at u with the mutation \(u^*\) such that u and \(u^*\) form an exchange pair. Let \(t, t'\) be (not necessarily distinct) indecomposable objects of \(\mathscr {T}\). Then for any \(n \in \mathbb {Z}\), at least one of the homomorphism spaces

and

is zero.

Proof

Suppose that there is a non-zero morphism in \(\text {Hom}_{\frac{\mathscr {C}}{[\Sigma ^d \mathscr {U}]}}{}(\Sigma ^{nd} t, \Sigma ^d u^*)\), and a non-zero morphism in \(\text {Hom}_{\frac{\mathscr {C}}{[\Sigma ^d \mathscr {U}]}}{}(\Sigma ^d u^*, \Sigma ^{(n+1)d} t')\). We recall that

and that

This means that there is a non-zero morphism in \(\text {Hom}_{\text {mod }\Gamma _U}(F_U(\Sigma ^{nd} t), F_U(\Sigma ^d u^*))\), and a non-zero morphism in \(\text {Hom}_{\text {mod }\Gamma _U}(F_U(\Sigma ^du^*), F_U(\Sigma ^{(n+1)d}t'))\). By Lemma 4.2 the object \(F_U(\Sigma ^du^*)\) is simple, so these two morphisms must compose to a non-zero morphism from \(F_U(\Sigma ^{nd} t)\) to \(F_U(\Sigma ^{(n+1)d}t')\). Again by the above isomorphisms, this composed morphism means we have a non-zero morphism in \(\frac{\mathscr {C}}{[\Sigma ^d \mathscr {U}]}\) from \(\Sigma ^{nd} t\) to \(\Sigma ^{(n+1)d} t'\), hence also a non-zero morphism in \(\mathscr {C}\) from \(\Sigma ^{nd} t\) to \(\Sigma ^{(n+1)d} t'\). This is a contradiction of the fact that T is an Oppermann–Thomas cluster tilting object. This proves the lemma. \(\square \)

Lemma 4.4

Let \(\mathscr {C}\), T, and U be as in Definition 1.5. Suppose also that d is odd, and that U is mutable at u with the mutation \(u^*\) such that u and \(u^*\) form an exchange pair. Then for \(t \in \mathscr {T}\),

Moreover, at least one of \(\text {Hom}_{\frac{\mathscr {C}}{[\Sigma ^d \mathscr {U}]}}{}(\Sigma ^d t, \Sigma ^d u^*)\) and \(\text {Hom}_{\frac{\mathscr {C}}{[\Sigma ^d \mathscr {U}]}}{}(\Sigma ^du^*, \Sigma ^{2d}t)\) is zero.

Proof

By the definition of an Oppermann–Thomas cluster tilting object, there is a \((d+2)\)-angle

in \(\mathscr {C}\) with each \(u_i \in \mathscr {U}\). Then \(\text {Ind}_\mathscr {U}{}([\Sigma ^dt]) = \Sigma _{i=0}^d(-1)^i[u_i]\). For each \(u_i\), we see that \(u_i = u^{\beta _i} \oplus {\tilde{u}}_i\), where u is not a direct summand of \({\tilde{u}}_i\). Then we have that \([u]^*([u_i])\) is equal to the number of copies of u in this sum; that is \([u]^*([u_i]) = \beta _i\). We also have that

because for each indecomposable \(u_\alpha \) in \(\mathscr {U}\) not equal to u we have that \(\text {Hom}_{\mathscr {C}}{}(u_\alpha , \Sigma ^d u^*) = 0\) and by Definition 1.4 we have that \(\text {dim}_K\text {Hom}_{\mathscr {C}}{}(u, \Sigma ^d u^*) = 1\). This means we have that \([u]^*([u_i]) = \text {dim}_K\text {Hom}_{\mathscr {C}}{}(u_i, \Sigma ^d u^*)\).

We apply \(c_\mathscr {T}(u,\mathscr {U}){}\) to [t] and obtain

The last step here is by [11, Proposition 3.1].

By Lemma 4.3 at least one of these Hom-spaces is zero, and we have proven the lemma. \(\square \)

Lemma 4.4 allows us to show a sign coherence property of the c-vector:

Lemma 4.5

Let \(\mathscr {C}\), T, and U be as in Definition 1.5. Suppose also that d is odd, and that U is mutable at u with the mutation \(u^*\) such that u and \(u^*\) form an exchange pair. Then either \(c_\mathscr {T}(u,\mathscr {U}){}([t]) \ge 0\) for all \(t \in \mathscr {T}\), or \(c_\mathscr {T}(u,\mathscr {U}){}([t]) \le 0\) for all \(t \in \mathscr {T}\).

Proof

Suppose that there exist objects \(t^1, t^2 \in \mathscr {T}\) such that \(c_\mathscr {T}(u,\mathscr {U}){}([t^1]) > 0\) and \(c_\mathscr {T}(u,\mathscr {U}){}([t^2]) < 0\). By the definition of an Oppermann–Thomas cluster tilting subcategory, there are two \((d+2)\)-angles

and

in \(\mathscr {C}\) where each \(u_i^j \in \mathscr {U}\). This means that \(\text {Ind}_\mathscr {U}{}([\Sigma ^d t^j]) = \Sigma _{i=0}^d(-1)^i[u_i^j]\). By Lemma 4.4, we have that

with at least one of the terms on the right being zero. Then as we have assumed d is odd, and we know that the dimension of a space is always non-negative, we see that

and

This immediately gives us a contradiction by Lemma 4.3, and as such our initial assumption must be false. This proves the lemma. \(\square \)

Lemma 4.6

Let \(\mathscr {C}\), T, and U be as in Definition 1.5. Suppose that d is odd, and suppose that U is mutable at u with the mutation \(u^*\) such that u and \(u^*\) form an exchange pair. Let \(\phi \) be the morphism from \(\Sigma ^d u^*\) to \(\Sigma ^d e_d\) which comes from rotating the exchange \((d+2)\)-angle shown in Eq. (2). For any object \(z \in \mathscr {C}\), the morphism \(\phi \) induces the morphism \(\phi ^*: \text {Hom}_{\mathscr {C}}{}(\Sigma ^d e_d, z) \rightarrow \text {Hom}_{\mathscr {C}}{}(\Sigma ^d u^*, z)\). Then the cokernel of \(\phi ^*\) is \(\text {Hom}_{\frac{\mathscr {C}}{[\Sigma ^d \mathscr {U}]}}{}(\Sigma ^d u^*, z)\).

Proof

We have the rotated \((d+2)\)-angle

which gives a long exact sequence

We can obtain from this an exact sequence

It is enough to prove that \(\text {Im}(\phi ^*)\) is equal to \(\text {Hom}_{\mathscr {C}}{}^{[\Sigma ^d\mathscr {U}]}(\Sigma ^d u^*, z)\), where \(\text {Hom}_{\mathscr {C}}{}^{[\Sigma ^d \mathscr {U}]}(\Sigma ^d u^*, z)\) denotes the morphisms from \(\Sigma ^d u^*\) to z that factor through \([\Sigma ^d \mathscr {U}]\).

By exactness, we have \(\text {Im}(\phi ^*) = \text {Ker}(\delta ^*)\). Let an element \(\theta \in \text {Hom}_{\mathscr {C}}{}(\Sigma ^d u^*, z)\) be given such that \(\theta \) factors through \(\Sigma ^d \mathscr {U}\). Then \(\delta ^*(\theta ) = 0\), or we would have a non-zero morphism from \(\mathscr {U}\) to \(\Sigma ^d \mathscr {U}\). So \(\text {Hom}_{\mathscr {C}}{}^{[\Sigma ^d \mathscr {U}]}(\Sigma ^d u^*, z) \subseteq \text {Ker}(\delta ^*)\). Next, let \(\epsilon \in \text {Hom}_{\mathscr {C}}{}(\Sigma ^d u^*, z)\) be given such that \(\delta ^*(\epsilon ) = 0\). By exactness \(\epsilon \) factors through \(\Sigma ^d e_d \in \Sigma ^d \mathscr {U}\). Thus, \(\text {Hom}_{\mathscr {C}}{}^{[\Sigma ^d \mathscr {U}]}(\Sigma ^d u^*, z) = \text {Ker}(\delta ^*)\). \(\square \)

We may use these results to prove more properties of the c-vector.

Proposition 4.7

Let \(\mathscr {C}\), T, and U be as in Definition 1.5. Suppose that d is odd, and suppose that U is mutable at u with the mutation \(u^*\) such that u and \(u^*\) form an exchange pair.

-

(i)

If \(c_\mathscr {T}(u,\mathscr {U})([t]) \ge 0\) for all \(t \in \mathscr {T}\), then for any \(t \in \mathscr {T}\)

$$\begin{aligned} c_\mathscr {T}(u,\mathscr {U}){}([t]) = \text {dim}_K\text {Im}(\text {Hom}_{\mathscr {C}}{}(t, u) \xrightarrow {\delta _*} \text {Hom}_{\mathscr {C}}{}(t, \Sigma ^d u^*)) \end{aligned}$$where \(\delta \) is the morphism from u to \(\Sigma ^d u^*\) shown in the exchange \((d+2)\)-angle, as seen in Eq. (2).

-

(ii)

If \(c_\mathscr {T}(u,\mathscr {U})([t]) \le 0\) for all \(t \in \mathscr {T}\), then for any \(t \in \mathscr {T}\)

$$\begin{aligned} c_\mathscr {T}(u,\mathscr {U}){}([t]) = -\text {dim}_K\text {Im}(\text {Hom}_{\mathscr {C}}{}(t, u^*) \xrightarrow {\epsilon _*} \text {Hom}_{\mathscr {C}}{}(t, \Sigma ^d u)) \end{aligned}$$where \(\epsilon \) is the morphism from \(u^*\) to \(\Sigma ^d u\) shown in the exchange \((d+2)\)-angle, as seen in Eq. (3).

Proof

Firstly, let \(t \in \mathscr {T}\) be given. Then, as \(\mathscr {U}\) is Oppermann–Thomas cluster tilting, there is a \((d+2)\)-angle

in \(\mathscr {C}\) with each \(u_i \in \mathscr {U}\). By Lemma 4.4, we have that

where at least one of the terms on the right hand side is zero.

Part (i): As we have assumed that \(c_\mathscr {T}(u,\mathscr {U}){}([t])\) is non-negative and d is odd, we have that

We also have the exchange \((d+2)\)-angle

This induces a morphism

We may restate the claim as: For \(t \in \mathscr {T}\),

We have a long exact sequence

from which we obtain an exact sequence

As the category \(\mathscr {C}\) is 2d-Calabi–Yau , we may apply the Serre duality to this sequence to obtain the exact sequence

to which we can apply the standard duality functor to obtain the exact sequence

where \(\phi :\Sigma ^d u^* \rightarrow \Sigma ^d e_d\). By Lemma 4.6 we see that \(D\text {Im}(\delta _*) \cong \text {Hom}_{\frac{\mathscr {C}}{[\Sigma ^d \mathscr {U}]}}{}(\Sigma ^d u^*, \Sigma ^{2d} t)\). This proves part (i).

Part (ii): As we have assumed that \(c_\mathscr {T}(u,\mathscr {U}){}([t])\) is non-positive and d is odd, we have from Eq. (7) that

We also have the exchange \((d+2)\)-angle

This induces a morphism

As in the proof of part (i), we may rewrite the claim: for \(t \in \mathscr {T}\),

We have a long exact sequence

We wish to examine the image of \(\epsilon _*\); in fact, we aim to prove that it is isomorphic to \(\text {Hom}_\frac{\mathscr {C}}{[\mathscr {U}]}(t, u^*)\).

We calculate \(\text {Ker}(\epsilon ^*)\). Let an element \(\theta \in \text {Hom}_{\mathscr {C}}{}(t, u^*)\) be given such that \(\theta \) factors through \(\mathscr {U}\). Then \(\epsilon _*(\theta ) = 0\), or we would have a non zero morphism from \(\mathscr {U}\) to \(\Sigma ^d\mathscr {U}\). So \(\text {Hom}_{\mathscr {C}}{}^{[\mathscr {U}]}(t,u^*) \subseteq \text {Ker}(\epsilon _*)\). Now let \(\phi \in \text {Hom}_{\mathscr {C}}{}(t, u^*)\) be given such that \(\epsilon _*(\phi ) = 0\). By exactness we have that \(\phi \) factors through \(f_1 \in \mathscr {U}\). Thus, \(\text {Hom}_{\mathscr {C}}{}^{[\mathscr {U}]}(t,u^*) = \text {Ker}(\epsilon _*)\). This shows that

which proves the result.

4.2 Proof of Theorem C

We can use these results to prove our final claim. We restate Theorem C here:

Theorem 4.8

(sign coherence for c-vectors) Let \(\mathscr {C}\), T, and U be as in Definition 1.5. Suppose that d is odd, and suppose that U is mutable at u with the mutation \(u^*\) such that u and \(u^*\) form an exchange pair. Then either (i) or (ii) below is true.

-

(i)

\(c_\mathscr {T}(u,\mathscr {U})([t]) \ge 0\) for all \(t \in \mathscr {T}\) and

$$\begin{aligned} c_\mathscr {T}(u,\mathscr {U}){}([t]) = \text {dim}_K \text {Hom}_{\Gamma _T}(F_T(t), \text {Im}(\delta _*)) \end{aligned}$$where \(\delta \) is the morphism from u to \(\Sigma ^d u^*\) in Eq. (2) and \(\delta _* = F_T(\delta )\).

-

(ii)

\(c_\mathscr {T}(u,\mathscr {U})([t]) \le 0\) for all \(t \in \mathscr {T}\) and

$$\begin{aligned} c_\mathscr {T}(u,\mathscr {U}){}([t]) = -\text {dim}_K\text {Hom}_{\Gamma _T}(F_T(t), \text {Im}(\epsilon _*)) \end{aligned}$$where \(\epsilon \) is the morphism from \(u^*\) to \(\Sigma ^d u\) in Eq. (3) and \(\epsilon _* = F_T(\epsilon )\).

Note that if t is an indecomposable summand of T then \(F_T(t)\) is an indecomposable projective \(\Gamma _T\)-module. Hence \(\text {dim}_K\text {Hom}_{\Gamma _T}(F_T(t), M)\) is an entry in the dimension vector of M when \(M \in \text {mod}\Gamma _T\).

Proof

Lemma 4.5 says that either \(c_\mathscr {T}(u,\mathscr {U}){}([t]) \ge 0\) for all \(t \in \mathscr {T}\) or \(c_\mathscr {T}(u,\mathscr {U}){}([t]) \le 0\) for all \(t \in \mathscr {T}\). Assume the former and begin with the map obtained from the exchange angle

We can apply the functor \(F_T\) to obtain a commutative diagram

We may then apply the functor \(\text {Hom}_{\Gamma _T}(F_T(t), -)\) to this diagram to obtain

This actually gives us the following commutative diagram:

Combining this with Proposition 4.7(i), we obtain the required equality. The proof of part (ii) uses the same arguments.

5 A Counterexample

For a triangulated category \(\mathscr {C}\) with two cluster tilting subcategories \(\mathscr {T}\) and \(\mathscr {U}\), we always have sign coherence in the c-vector; that is, for a given \(u \in \mathscr {U}\) and for all \(t \in \mathscr {T}\), either \(c_\mathscr {T}(u,\mathscr {U}){}([t]) \ge 0\) or \(c_\mathscr {T}(u,\mathscr {U}){}([t]) \le 0\). We demonstrate an example here where this sign coherence is not achieved for a higher case.

We will be working with the \((d+2)\)-angulated higher cluster categories of type \(A_n\). We will label them as \(\mathscr {C}(A_n^d)\).

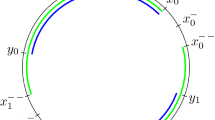

The following description of \(\mathscr {C}(A_n^d)\) is a restatement of Propositions 3.12 and 6.1 and Lemma 6.6(2) in [9]. We take the canonical cyclic ordering of the set \(V = \{1, \ldots , n + 2d+1\}\), which it can be helpful to think of as the vertices of an \((n + 2d + 1)\)-gon labelled in a clockwise direction. This means that for three points in our ordering x, y, z such that \(x< y < z\), if we start at x and move clockwise, we will encounter first y then z. It is worth noting that if we have \(x< y < z\), then we also have that \(y < z \le x\) and \(z \le x < y\). For a point x in our ordering, we denote by \(x^-\) the vertex of our polygon that is one step anticlockwise of x.

Proposition 5.1

The indecomposable objects of \(\mathscr {C}(A_n^d)\) are in bijection with subsets of V that have size \(d+1\) and contain no neighbouring vertices. We identify each indecomposable X with its subset of V, and will write \(X = \{x_0, x_1, \ldots , x_d\}\).

We see immediately that by setting \(d=1\) in Proposition 5.1, we obtain the traditional cluster category of type \(A_n\).

Using the identification described in Proposition 5.1, we can easily describe the action of the translation functor, and also how the indecomposable objects interact with one another.

Proposition 5.2

The translation functor simply shifts an indecomposable by one place; that is, if \(X = \{x_0, x_1, \ldots , x_d\}\), then \(\Sigma ^d(X) = \{x_0^-, x_1^-, \ldots , x_d^-\}\).

Definition 5.3

For two indecomposable objects X and Y of \(\mathscr {C}(A_n^d)\), we say that X and Y intertwine if there is a labelling of \(X = \{x_0, x_1, \ldots , x_d\}\) and of \(Y=\{y_0, y_1, \ldots , y_d\}\) such that

We see that Definition 5.3 is symmetric; we take \(Y = Y'\), where we choose the labelling as \(y_i' = y_{i-1}\) for \(1 \le i \le d\) and \(y_0' = y_d\). This gives us that

as required.

For two indecomposable objects X and Y of \(\mathscr {C}(A_n^d)\), either \(\text {Hom}(X, Y) = 0\) or \(\text {Hom}(X, Y) = K\); this is the same as in the classic cluster category. In fact, we have the following:

Proposition 5.4

[9, Proposition 6.1] For two indecomposable objects X and Y of \(\mathscr {C}(A_n^d)\), we have \(\text {Hom}(X, Y) = K\) if and only if X and \(\Sigma ^{-d}(Y)\) intertwine. This is equivalent to X and Y having labellings such that the following is true:

We may also speak to whether or not there is a factorisation of a non-zero homomorphism in \(\mathscr {C}(A_n^d)\).

Proposition 5.5

[9, Proposition 3.12] For two indecomposable objects X and Y of \(\mathscr {C}(A_n^d)\) satisfying the condition in Proposition 5.4, a non-zero morphism \(X \rightarrow Y\) factors through a third irreducible Z if and only if there exists a labelling for \(Z=\{z_0, z_1, \ldots , z_d\}\) such that

It is also true, again due to [9], that our categories \(\mathscr {C}(A_n^d)\) permit Oppermann–Thomas cluster tilting objects. By [9, Theorem 2.4] and [9, Theorem 6.4], the sum T of \({n + d - 1 \atopwithdelims ()d}\) mutually non-intertwining indecomposable objects is an Oppermann–Thomas cluster tilting object. Combining this with [9, Lemma 6.6] gives us the following Proposition:

Proposition 5.6

The sum T of \({n + d - 1 \atopwithdelims ()d}\) mutually non-intertwining indecomposable objects of \(\mathscr {C}(A_n^d)\) is an Oppermann–Thomas cluster tilting object. Moreover, this describes all such objects. These objects are maximal with respect to the non-intertwining property.

We now state the counterexample: Let \(\mathscr {C} = \mathscr {C}(A_3^3)\). We let T be the object given by summing all of the indecomposables containing the vertex 1, and U be the object obtained by summing all of the indecomposables containing the vertex 3. In both cases the indecomposables are obviously non-intertwining and there are \({5 \atopwithdelims ()3}\) of them, so by Proposition 5.6 both T and U are Oppermann–Thomas cluster tilting objects. Let \(\mathscr {T} = \text {add}(T)\) and \(\mathscr {U} = \text {add}(U)\) be the Oppermann–Thomas cluster tilting subcategories associated with these objects.

We set \(u = \{3,5,8,10\} \in \mathscr {U}\). We will examine the action of the c-vector \(c_\mathscr {T}(u,\mathscr {U}){}\) on \(\mathscr {T}\).

We take the indecomposable \(t_1 =\{1,4,6,9\} \in \mathscr {T}\). By Theorem 4.1, we can calculate \(c_\mathscr {T}(u,\mathscr {U}){}([t_1])\) by taking the coefficient of [u] in \(\text {Ind}_\mathscr {U}{}([\Sigma ^3 t_1])\) and multiplying by \((-1)^3 = -1\). By Proposition 5.2 we see that \(\Sigma ^3 t_1 = \{3,5,8,10\}\), which is equal to u. Then \(\text {Ind}_\mathscr {U}{}([\Sigma ^3 t_1]) = [u]\), so we have that \(c_\mathscr {T}(u,\mathscr {U}){}([t_1]) = -1\).

We take the indecomposable \(t_2 =\{1,5,7,9\} \in \mathscr {T}\). Again, we calculate \(\Sigma ^3 t_2 = \{4,6,8,10\}\). This is not in \(\mathscr {U}\), so we need to find the 5-angle made up of objects in \(\mathscr {U}\) that covers this to give us the index. We aim to do this using [9, Theorem 6.3]. Firstly, we select an element of \(\mathscr {U}\) which intertwines \(\Sigma ^3 t_2\); we take \(\{3,5,7,9\}\). This gives us the 5-angle

As each object in the angle except for \(\Sigma ^3 t_2\) is in \(\mathscr {U}\), we have that

It follows that \(c_\mathscr {T}(u,\mathscr {U}){}([t_2]) = 1\). This demonstrates that there exist indecomposables in Oppermann–Thomas cluster tilting subcategories for \(d>1\) that do not have sign coherence in their c-vector. It also means that by Lemma 4.5, u is not mutable in \(\mathscr {U}\).

References

Dehy, R., Keller, B.: On the combinatorics of rigid objects in 2-Calabi–Yau categories. Int. Math. Res. Not. 2008, rnn029-17 (2008)

Demonet, L., Iyama, O., Jasso, G.: \(\tau \)-tilting finite algebras, bricks and g-vectors. Int. Math. Res. Not. 2019, 852–892 (2017)

Geiss, C., Keller, B., Oppermann, S.: n-angulated categories. J. Reine Angew. Math. 675, 101–120 (2013)

Iyama, O.: Higher-dimensional Auslander–Reiten theory on maximal orthogonal subcategories. Adv. Math. 210, 22–50 (2007)

Jacobsen, K., Jørgensen, P.: \(d\)-Abelian quotients of \((d+2)\)-angulated categories. J. Algebra 521, 114–136 (2019)

Jørgensen, P.: Tropical friezes and the index in higher homological algebra. Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society (to appear)

Jørgensen, P., Yakimov, M.: c-vectors of 2-Calabi–Yau categories and Borel subalgebras of \({\mathfrak{sl}}_{\infty }\). Sel. Math. (N.S.) 26, 71–90 (2020)

Nájera Chávez, A.: On the c-vectors of an acyclic cluster algebra. Int. Math. Res. Not. 6, 1590–1600 (2015)

Oppermann, S., Thomas, H.: Higher-dimensional cluster combinatorics and representation theory. J. Eur. Math. Soc. (JEMS) 14, 1679–1737 (2011)

Palu, Y.: Cluster characters for triangulated 2-Calabi–Yau categories. Ann. Inst. Fourier (Grenoble) 58, 2221–2248 (2008)

Reid, J.: Indecomposable objects determined by their index in higher homological algebra. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 148, 2331–2343 (2020)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Bernhard Keller.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Reid, J. Tropical Duality in \((d+2)\)-Angulated Categories. Appl Categor Struct 29, 529–545 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10485-020-09625-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10485-020-09625-7

is closed under sums and summands, and contains the

is closed under sums and summands, and contains the  contains a

contains a  if and only if the

if and only if the  . This sequence is known as the left rotation of sequence (

. This sequence is known as the left rotation of sequence ( has the following extension property:

has the following extension property: