Abstract

This scoping review maps recent research into peer navigation programs for people living with HIV. Four databases were systematically searched in June 2020. Results were screened according to defined criteria and were not restricted to any design, outcome or country. Six papers drew from randomised control trials, five from quasi-experimental or pragmatic trials, and four panel, eight qualitative, three mixed method and one cross-sectional designs were included for review. Programs incorporated health systems navigation and social support. Authors provided strong theoretical bases for peers to enhance program effects. Studies primarily reported program effects on continuum of care outcomes. Further research is required to capture the role HIV peer navigators play in preventing disease and promoting quality of life, mental health, and disease self-management in diverse settings and populations. Peer programs are complex, social interventions. Future work should evaluate detailed information about peer navigators, their activities, the quality of peer engagement as well as employee and community support structures to improve quality and impact.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

The involvement of people living with HIV in their own care and wellbeing is a hallmark of responses to HIV and AIDS in many places around in the world. The meaningful involvement of key populations of people living with and affected by HIV, including gay men and their allies, sex workers and people who inject drugs has underpinned successful national HIV strategies, with peer and community-based responses now recognised globally as critical to meeting contemporary efforts to end the epidemic [1, 2].

For over 40 years, researchers have described and assessed the effectiveness of peer and community-based responses in a number of areas of health [3,4,5]. While diverse in its traditions and conceptualisations, the role of peers in health promotion relies on the affinity, connection and experiences peers share with their communities to enable effective communication, education, advocacy and social support [4, 6]. Since the arrival of antiretroviral therapy (ART) most research in HIV has focused on people living with HIV assisting peers in healthcare settings to live well with chronic manageable illness [3, 7]. The engagement of communities as partners, leaders and decision-makers in national health systems and HIV strategies, however, remains limited. A lack of contemporary investment in these responses is a major barrier to meeting global elimination targets for HIV [8].

People living with HIV have also taken up the role of health systems navigation. As a patient-centred model of care developed in cancer treatment and other areas of healthcare, peer navigators provide guidance and support through complex health systems, acting as a bridge between clinical and community services and social supports [9,10,11,12]. As peers are resourced with training, supervision, pay and other employment conditions, a growing body of practice-based evidence, guidelines and standards now position peer navigation as a more formal occupation for peers working alongside other healthcare practitioners in the HIV care and support sector, particularly in high-income settings [13,14,15,16,17,18].

Evidence reviews which have systematically assessed the impact of HIV peer navigation programs and similar peer interventions have largely focused on the efficacy of programs to strengthen the treatment cascade [3, 7, 10, 19, 20]. The dual benefits of disease and primary prevention that highly effective ART affords has driven the establishment of the ’90 90 90’ global treatment targets [21]. By 2020, according to global estimates, 81 per cent of people living with HIV knew of their positive status, 67 per cent of people diagnosed were receiving sustained treatment and 59 per cent of those on treatment were virologically suppressed [22]. Although high quality designs have shown for some time that peer navigation and peer interventions can improve these continuum of care outcomes for individuals in experimental settings, until recently results have lacked consistency [7].

Diverse results from randomised control trials (RCTs) evaluating peer navigation programs are challenging to interpret. This is in part because many published reports do not provide full descriptions of how programs operate to achieve desired effects [6, 10]. The most recent systematic review and metanalysis, which limited results to studies evaluating in-person and individually tailored peer navigation and support interventions, found more consistent evidence that this approach was superior to standard care in supporting HIV continuum outcomes [7]. The influence of other program mechanisms and qualities such as the nature of peer navigator activities and their characteristics, skills, training and employment and support structures are less well understood [6, 10]. Recent systematic reviews also have not considered evidence from qualitative and non-experimental designs that may help address factors relevant to the implementation and improvement of HIV peer navigation programs.

Improving quality of life and chronic healthcare outcomes for people living with HIV is now a major focus of the global HIV response [23]. Addressing stigma, social isolation, insecurity, non-communicable diseases like depression and anxiety as well as the detection and treatment of opportunistic infections, particularly in resource-poor settings, will be vital to improve not only the quality of life that people living with HIV experience but also global treatment goals and targets for the reduction of new infections and deaths [8]. Despite this, fewer evidence reviews have considered results from studies which show how peer navigation programs can improve health and wellbeing outcomes beyond the treatment cascade [3, 7].

This scoping review examined the extent and nature of research into peer navigation services for people living with HIV. It aimed to [1] define how HIV peer navigation programs are conceptualised and operationalised within the research literature; [2] determine what health outcomes programs aim to effect and how these are framed, captured and reported; and [3] identify priorities for research and improving the quality and impact of services. This detailed synthesis of form, function and reported outcomes will be useful to program planners, policy makers and researchers. Identifying the underlying mechanisms for action and the factors that contributed to program effectiveness in different contexts will help to facilitate improved design, scale-up, impact and evaluation of peer navigation programs in diverse settings and populations of people living with HIV.

Methods and Design

Our review broadly followed frameworks for scoping reviews outlined by Arksey and O’Malley and refined by Levac et al. [24, 25]. PRISMA guidelines [26] were followed for reporting (see Supplementary Material 1 for a completed checklist).

Inclusion Criteria

This study included original peer-reviewed research papers which investigated the effects, context, and delivery of HIV peer navigation programs. Evidence reviews and papers reporting protocols and baseline data were not included. Studies were not restricted to any design, outcome or geographic region and targeted people living with HIV 18 years or older.

We screened for papers that reported use of peer navigation or similar services. To support the overall aims of the scoping review we used broad search terms that would identify studies that investigated peer navigation services even if the term was not used to describe the intervention or program. If authors did not use the term peer navigation, for a paper to be included navigators were HIV positive and offered in-person, tailored support to individuals within a formalised role (rather than personal relationships and social networks) and provided links to social support, healthcare or community services.

Identifying Relevant Studies

We searched articles indexed in Embase, MEDLINE, Psych Info and CINAHL on June 22, 2020. Results were limited to papers published in English. Our search was restricted from 2015 onwards, when international targets were first established to treat 90 per cent of people living with HIV [21]. This captured HIV peer navigation programs and studies operating in the contemporary ‘treatment cascade’ environment.

Our search strategy developed keywords and terms relevant to people living with HIV and peer navigation. Keywords and search terms included: people, men or women living with HIV or HIV/AIDS; HIV or HIV/AIDS patients, support or care; PLHIV, PLHWA, Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and HIV seropositivity. The above terms were combined with peer navigation, counselling, support, help, mentor or education and patient navigation or advocacy. See Supplementary Material 2 for a sample search strategy.

Two reviewers independently screened subsets of titles and abstracts using the inclusion criteria to identify potentially relevant studies. The study team then met several times to discuss discrepancies and review the search strategy and inclusion criteria based on results. Following initial screenings of abstracts and titles, the full papers of articles were reviewed for relevance against finalised criteria. Additional papers or sub-studies published using data from the studies captured by our search were included for analysis if they met inclusion criteria. The authors of papers were not contacted for clarification or additional information as our review aims were concerned with assessing how information about peer navigation programs and their outcomes were framed, captured and reported in published materials.

Data Extraction and Analysis

All members of the study team collaboratively drafted a data charting form containing 10 variables relating to our research aims. We aimed to capture data on research settings, methods, aims, target populations and reported outcomes as well as descriptions of program personnel, peer navigator roles, program activities and logics or underlying theorical frameworks used to explain program effects.

The first author imported the full text of papers into NIVO software, generating first codes and then summaries related to each of these variables. Codes and the data charting form were both reviewed and modified in meetings between the study team as this analysis was completed. Summaries were then further refined during meetings with attention paid to commonalities and connections across the sample and implications within the broader research literature to determine research priorities and recommendations for program implementation and improvement.

Our review appraised factors related to the conceptualisation and implementation of peer navigation interventions to provide recommendations for the improvement of program quality and impact. No formal critical appraisal, assessment of the risk of bias or statistical metanalysis of quantitative data were proposed due to the heterogeneity of study designs.

Results

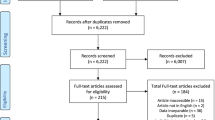

Twenty-seven papers investigating nineteen unique peer navigation programs and implementation settings were included in this review [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53]. Our database search identified 1143 records. Following the removal of duplicates, the abstracts and titles of 668 papers were screened, followed by the full text and supplementary materials of 127 papers, resulting in 644 exclusions. Three papers that published data related to studies identified by our search met criteria and were included for review. Table 1 provides a summary of the publication details, design, participants and outcomes for each study included in the review.

Research Design, Settings and Participants

Our search captured a range of study designs, including six papers that reported results from four RCTs, five papers drawing from four quasi-experimental or pragmatic trials, and four panel, eight qualitative, three mixed method and one cross-sectional designs. As indicated in Table 1, this includes related papers and sub-studies reporting data from trials investigating the same peer navigation program or implementation setting.

As shown in Table 2, nine studies were based in the United States. Our search also found research investigating peer navigation programs and implementation settings in Malawi, Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, Ethiopia, Nigeria, South Africa, India and Mexico. All five of the studies conducted entirely in rural areas were in sub-Saharan Africa. Three studies conducted in the United States and Malawi collated data from multiple sites across rural and urban areas. Ten programs were delivered by clinics or healthcare providers, three by community health organisations and two studies collated and compared data from programs operating across both clinical and community settings (see Table 2). Two programs operated in incarcerated or post-release settings.

Table 1 shows that our review found studies investigating programs proposed for or targeting key populations of people living with HIV such as women and mothers, men who have sex with men, trans women, sex workers, people who use drugs, people being released from incarceration, racial and ethnic minorities and youth and young people. Papers also targeted people living with HIV identified as having additional risk-factors such recent diagnosis, loss to care or substance use (see Table 1). Participants and key informants included peer workers, service providers and clinicians.

HIV Peer Navigation Concept and Operation

Our search identified a range of titles and terms to describe peer navigation roles and programs. Peer navigation was the most common term, however, programs and roles very similar in scope and function were also called patient or health navigation, peer or patient mentoring, peer support, community health workers, ‘mentor’ or ‘expert’ mothers as well as terms drawing on local language and traditions for peer and community-based support for health and wellbeing (see Table 2).

A new iteration of peer support and patient navigation

Peer navigation was closely linked to the concept of patient or health systems navigation. As a model of care well-established in healthcare systems and the broader research literature, it was common for authors [32, 33, 37, 38, 42, 43, 46, 48, 49] to draw on the principles and approaches underpinning patient navigation when describing the overarching aims and functions of peer navigation programs. Namely, that peer and patient navigation provide linkages and patient-centred support to overcome health system barriers, improving healthcare engagement and clinical care outcomes. In this way, peer navigation was often framed as a type or recent adaptation of patient navigation. Researchers that used this framing positioned peers as logical interventionist to take up these roles, noting that patient navigation is generally performed by lay workers and paraprofessionals, and that peers possess qualities and experiences that may enhance their effectiveness [32, 33, 42, 46, 48, 49]. Studies which did not explicitly conceptualise programs as peer or patient navigation [29, 36, 38, 39, 44, 45, 50,51,52] alternatively built on traditions of peer and lay health worker participation in health promotion for people living with HIV. These authors generally cited evidence that peer education and support are widespread in healthcare and that these interventions are effective for HIV prevention and improving clinical care outcomes for people living with HIV.

To inform the design and implementation of peer navigation programs our review further identified how authors defined peers and their activities, as well as theories that were tested or developed which would explain the mechanisms through which peer navigators effected health outcomes. For ease of reporting, program qualities for related papers and sub-studies are reported together across Tables 3 and 4 to provide a total of nineteen peer navigation programs and settings for implementation.

Peer navigator characteristics and roles

Our review aimed to clarify the definition of a peer navigator by restricting inclusion to programs involving people living with HIV as navigators, except in cases where the term peer navigation was explicitly used by authors.

Researchers generally incorporated information about the key characteristics, circumstances and experiences of peer navigators to establish their peer status or discuss the theoretical basis, operation and effects of programs. There were only two studies that did not provide enough detail in published materials about the selection of peer navigators to determine whether living with HIV was a factor in establishing peer status (see Table 3). One program proposed that the selection of peer navigators would include but not be limited to people living with HIV. Otherwise, sub-group characteristics constituted peer status in addition to living with HIV. These included gender, sexuality, trans experience, ethnic or racial background, history of drug use or incarceration, taking ART, and being a mother, a client at the same clinic or open and willing to discuss living with HIV (see Table 3).

Reported requirements for formal qualifications or levels of education were minimal (see Table 3), with emphasis placed on the skills and experiences navigators were likely to have as peers. Studies which operationalised or evaluated programs consistently included at least some information about the training made available to peer navigators (see Table 3). Most often these were short courses or on-the-job training focused on content in-line with expected duties. As shown in Table 3, eleven studies reported information about supervision and organisational support for peer navigation roles. Supervision most commonly took the form of a program coordinator reinforcing training and providing feedback on performance and client work.

It was possible to determine whether peer navigators were volunteers, employed or paid a stipend for fourteen studies, however, this information was not always available or uniformly reported (see Table 3). Among the authors who indicated that peer navigators were employed, three did not include information about rates of pay or hours worked. The authors of three studies did not include any information about the pay and conditions of peer navigators.

Program activities

Our review identified activities that were common for peer navigators to perform as well as the mode, duration and mechanisms of peer engagement.

A wide range of modalities for peer navigator and client contact were envisioned and are summarised in Table 4. These included face-to-face support sessions at the premises of implementing clinics, hospitals, community health organisations and correctional facilities, outreach in community and the homes of clients as well as accompaniment to appointments and voice or text contact via phones, particularly for follow-up appointments or reminders. The duration of client contact with programs was not always reported, but generally, peer navigation interventions were short-term and intensive, involving a high frequency or unlimited amount of contact across several modes for less than 6-months. It was less common for demand or program protocols to extend beyond 6-months, however, two programs focusing on reproductive and maternal health outcomes extended beyond one year (see Table 4). Four programs described brief interventions with limited contact including one in which peer navigators communicated with clients exclusively through phone calls or text.

As shown in Table 4, education and the provision of information were the most common duties for peer navigators to undertake, followed by health service linkage and referral. Communication and clinical liaison activities were also consistently described by researchers, which included reminders and follow-up for missing appointments and in some cases providing feedback about client experiences. Eleven studies outlined emotional and social support and ten identified coaching and skills building as part of the work of navigators. Programs in nine studies provided practical support and material aid, such as transport, financial support and accompanying clients to appointments. Only the authors of three studies described the work of navigators as advocating on behalf of clients in healthcare settings or instances of poor treatment.

Program mechanisms

Authors’ discussions of the theoretical foundation for these activities to support health outcomes incorporated elements of social learning theory and social support frameworks, the information-motivation-behavioural skills (IMB) model for behaviour change as well as patient-centred, strengths-based and social empowerment perspectives (see Table 4). Researchers also offered explanations as to why peers living with HIV may be uniquely skilled at performing these activities or more effective at influencing desired outcomes. Although an underlying framework was not always identified, program theories, hypotheses and mechanism centred on the ability of navigators to build on their shared experiences, circumstances or affinity with peers to establish trust, credibility, empathy and understanding or inspire role modelling, motivation and empowerment.

As outlined in Table 4, it was most common for authors to highlight the higher degree of credibility and trust peers are likely build with people living with HIV. Trust was linked to peers belonging to the same stigmatised group or being viewed as having credible insight into overcoming challenges, due to having managed similar stressors and life circumstances. People living with HIV were therefore thought to be more likely to uptake information, referrals, behaviours and beliefs promoted by peers.

Similarly, authors argued that navigators can use their greater understanding of peers’ life circumstances to offer the most relevant and helpful information, referrals, strategies and practical support. Peer navigators’ understanding of the lived experience of HIV was also theorised to contribute to their ability to generate empathy with clients and in turn enhance how the emotional and social support they provided was received. As a strong source of emotional support, authors argued that the peer relationship would empower resilience, improve motivation or act as a buffer from the negative effects of stigma and discrimination on mental wellbeing, medical adherence and healthcare engagement. The authors of one paper also suggested that as peers are more resilient and attuned to the nuances of HIV stigma and discrimination that they would be more effective advocates in instances of poor treatment (see Table 4).

Role modelling was another common mechanism of peer navigation programs, identified by the authors of eight studies (see Table 4). Researchers positioned peer navigators who come from similar backgrounds and experiences as clients and patients as having a strong influence on showing them how to overcome their own challenges and stressors. Modelling success and healthy living was also seen as one way in which the peer relationship motivates and empowers people living with HIV to achieve desired health outcomes.

Most often hypotheses and rationales for peer involvement were outlined in descriptions of interventions or discussions of program effects, however, studies with significant qualitative components [31, 34, 41, 42, 53] provided theory development or rich description of these activities and processes. Researchers reporting on four programs [27, 29, 35, 36, 40, 45] did not include a clear justification for peer engagement grounded in a consideration of the influence of peer skills and characteristics on program operation or effects.

Health Outcomes

Our review found that recent research into peer navigation has predominately focused on programs aiming to strengthen the HIV treatment cascade.

Primary health outcomes

The primary endpoints reported by twenty-five papers were continuum of care outcomes (see Table 5). Only two studies, which investigated the acceptability of peer navigator referral to screening for cervical cancer and peer-based assistance for accessing healthcare, community and social support did not investigate a program primarily aiming to influence treatment cascade outcomes.

As Table 6 shows, the most common health outcomes papers reported on related to linkage to and retention in HIV care, followed by improvement in virological suppression and ART initiation or adherence. This included five papers reporting on results from RCTs, of which one found evidence of greater virological suppression when compared to controls while four did not. Three out of five papers reporting results from RCTs saw greater uptake and retention in care compared to controls, and one out of three reported greater uptake and adherence of ART. All pragmatic trials, quasi-experimental and longitudinal or panel designs found evidence of improvement in continuum of care outcomes, including virological suppression, ART initiation or adherence and retention in care. In one trial improved retention in care did not lead to better virological suppression. In another, stronger retention in care was observed but improved ART initiation was not.

Of the studies with qualitative components, four papers developed program theory and provided descriptions of the processes and mechanisms that led to effects on HIV care continuum outcomes (see Table 5). Studies also explored the needs of target populations in relation to healthcare engagement and the HIV continuum of care [29, 31, 46] or described enablers and barriers for successful implementation [42, 47, 52]. The feasibility [34, 49], acceptability [29, 34, 46, 49, 53] and safety [34] of programs targeting these outcomes were also assessed, with positive results.

The primary endpoints of six papers also included the prevention of HIV (see Table 5). Of these, one RCT reported a reduction in condomless sex which risked transmission and one pragmatic trial reported no change in condom use or number of partners. Among the two studies that aimed to show the effect of peer navigation programs on behaviours related to HIV prevention during pregnancy, support was shown to promote infant diagnosis [51], and treatment initiation and uptake of maternal prevention programs [45, 50]. Reducing risk behaviours related to drug and alcohol use was a primary outcome of a program investigated by one RCT [43] which found no significant effect when compared to the control group.

Secondary health outcomes

Our analysis also identified health outcomes that researchers either considered secondary or viewed in terms of their contribution to HIV care continuum outcomes. Secondary health outcomes are summarised in Table 6. These included health outcomes that would enable greater self-management of HIV, such as improvement in self-efficacy, the uptake of knowledge and skills related to HIV care and treatment and engagement with healthcare professionals and other supports. Of the studies which assessed these outcomes, one panel study found evidence of improvement in HIV knowledge and one out of two papers from RCTs reported improvement when compared to controls, while there was no reported improvement in self-efficacy from the intervention (see Table 6). Two papers based on results from RCTs reported increased engagement in healthcare engagement while one did not. Qualitative and mixed methods studies also described how programs addressed these outcomes.

Table 6 shows that 4 studies detailed how programs addressed or affected factors related to quality of life as secondary outcomes, such as the impact of HIV on general health and function, and the influence of HIV, stigma and discrimination on self-esteem, mental health, social wellbeing and relationships. Of these, two papers utilising RCTs reported no improvement in validated measures of health-related quality of life and one panel study reported improvement in quality of life related to physical health and perceived levels of stigma and social support. One qualitative study developed theory and provided recommendations for the activities and mechanisms that could improve factors related to HIV and quality of life, such as mental health and broader wellbeing (see Table 6).

Discussion

Peer navigators and their effects

Our review aimed to clarify peer navigation as a distinct service model for the promotion of health among people living with HIV, offering a synthesis of the form, function and outcomes of programs found in the recently published research literature.

The peer navigation programs captured by our search incorporated key elements of health systems navigation as well as roles traditionally fulfilled by peers to promote the health and wellbeing of people living with HIV. The peer status of navigators was primarily established by living with HIV and navigators often shared sub-group characteristics with target populations. Peer navigators operated in formalised roles, either as employees or volunteers in healthcare settings and community health organisations providing linkage and referral to health services and community and social support. Navigators were selected for the skills and characteristics they were likely to have as peers, rather than formal education or qualifications. Peer navigators were also provided with role-specific training, supervision and support to fulfil their duties. Their activities fell into the broad categories of providing linkage and referrals to health services, liaison and communication between clinical services and clients, practical support and material aid, education and informational support, coaching and skills building, emotional and social support and less frequently, patient advocacy. Within this scope, interventions provided tailored support to individuals and were generally intensive and short-term in nature.

Across the studies in our review, we found strong justification for peer navigators to perform these roles and activities based on explanations of how peer engagement enhanced the effectiveness of programs. The program theories and mechanisms described by researchers centred on the ability of peer navigators to build on their shared experiences, circumstances or affinity with target groups to establish trust, credibility, empathy and understanding or inspire role modelling, motivation and empowerment. These discussions are strongly aligned with the broader literature on the socially supportive role of peers in health promotion [4, 6, 54, 55] and were informed by robust theoretical frameworks including the information-motivation-behavioural skills (IMB) model [56], social support frameworks [57,58,59] and social learning theory [60], as well as patient-centred, strengths-based and social empowerment perspectives [61, 62], positioning peer navigators to effectively influence a wide-range of desired health behaviours and outcomes.

The studies captured by our review primarily provided evidence of the ability of peer navigation programs to strengthen the HIV continuum of care. Outcomes from more rigorous designs which combined randomisation and control groups were less consistent. Many studies demonstrated how peer navigation programs addressed the prevention of HIV, quality of life, mental health and wellbeing and disease self-management but fewer captured effects or detailed descriptions of the processes through which programs influence these outcomes.

Priorities for research

The mechanisms and activities of the peer navigation programs we reviewed addressed a wide range of health outcomes and behaviours. While strengthening the continuum of care was often predicated on improvement in areas such as quality of life, mental health and wellbeing, or disease-self management researchers often did not conceptualise these as significant goals in their own right. Unless considered in terms of its contribution to the HIV care continuum, the influence of peer navigation programs on these outcomes were subsequently captured much less consistently. Apart from HIV prevention, substance dependence and screening for cervical cancer, the influence of peer navigation on health promotion and prevention of comorbidities among people living with HIV were not addressed as primary outcomes by the studies captured in this review.

Given the strong theoretical basis set out by researchers for peer navigators to promote health and wellbeing for people living with HIV, there is a significant justification for more research to demonstrate the effects of peer navigation on these health outcomes. Particularly, the detection and treatment of other disease and opportunistic infections, which are among the leading causes of HIV-related mortality globally [63, 64]. Evidence which has only begun to enter the research literature also suggests that chronic healthcare outcomes which reach beyond medical adherence are a priority for peer navigation programs operating in high-income settings which already have strong continuum of care outcomes [65]. With the ultimate goals of successful treatment for any person living with HIV being to prevent death, disease and improve overall health, wellbeing and quality of life, it remains a priority globally to understand how effectively peer navigation can address these outcomes directly.

Our review also demonstrates a need for research to build the evidence base for peer navigation programs operating in diverse settings and healthcare systems. Studies investigated programs proposed for all key populations. Evaluations of programs which targeted all people living with HIV generally provided information about the characteristics and risk-factors of study participants. However, our review shows that this research is concentrated on peer navigation programs operating in large urban centres in the United States, which was the only highly resourced healthcare system investigated by studies in our review. Our search identified research conducted in Mexico, India and seven countries in sub-Saharan Africa. The studies that we reviewed reported that intersecting forms of HIV-based stigma, discrimination, criminalisation, the high cost of healthcare and a lack of an enabling environment for key populations of women, sex workers, gay and bisexual men and men who have sex with men, people who use drugs, ethnic minorities and trans people were barriers to the effectiveness of peer navigation programs and health and wellbeing outcomes for people living with HIV [29, 31, 34, 41, 44, 46, 48, 49, 52]. No other studies targeted regions in which the HIV response has recently been identified as going backwards, such as Eastern Europe, Central Aisa, the Middle East, North Africa and Latin America [8]. Researchers who collaborate with communities in these regions are well positioned to demonstrate how peer navigation programs respond to drivers of the epidemic and HIV-related disparities and inequalities in these systems.

In many places around the world peer-based responses are well-established [1] and initiatives such as peer navigation programs are delivered by peer-led community organisations representing people living with HIV and affected communities [11,12,13,14,15,16]. However, this, too was not reflected in the research captured in our review. Studies mostly investigated programs operated and managed by clinics employing peer staff. In some cases [27, 35], the scope of programs was limited to direct liaison between clinical providers and their clients, performing tasks such as reminders and follow up for appointments and medical adherence. As a result, the research literature risks constructing a limiting and largely medicalised role for HIV peer navigators in health systems. Peer-led organisations with strong links to local communities and expertise in the delivery of peer-based programs are likely to have different priorities, as well as unique strengths and challenges in implementing peer navigation programs which should be explored [66].

Similarly, the strategies and mechanisms employed by peer navigation programs often imply a multi-sectoral approach. Only five studies, however, investigated programs operated by or in collaboration with community health organisations. Reported collaboration between implementing clinics and community health organisations in our sample was largely limited to the development of referral pathways between healthcare and other social services and the recruitment of peer staff. Peer-based programs are known to drive improvement and enhance the effectiveness of healthcare systems while significant adaptation and engagement between clinical and community partners is likely to be required to deliver programs across clinical and community settings [66]. As community health organisations and third sector NGOs play a large role in the commission and delivery of HIV programs globally, understanding how peer navigation programs respond to and operate in these settings remains a priority.

Improving evaluation, quality and impact of peer navigation programs

Our review also provides guidance on how researchers can continue to contribute to improving the quality and impact of peer navigation programs.

The strong theorical basis set out by authors to justify peer engagement to deliver health systems navigation represents an advancement in the conceptualisation and design of peer navigation programs and similar peer interventions as described in the research literature. In line with guidance from Simoni et al., [6] researchers should clearly define who peers navigators are, and with reference to an appropriate underlying theoretical framework, provide an explanation of how their characteristics, skills and experiences enhance program activities and desired effects. Researchers who continue to think carefully and conceptually about intervention design will be able to contribute to the development and improvement of approaches for peer navigation to promote a wider range of health outcomes for people living with HIV.

Our recommendations draw attention to how the desired effects of peer navigation programs are identified, measured and evaluated. Our analysis of the activities and mechanisms described in papers affirms that peer navigation programs are inherently complex, social interventions. Programs mediate the intersection between HIV and the psychological, social and healthcare contexts of people living with HIV. Only a small number of studies in our review aimed to capture program effects on culturally and contextually informed assessments of health and wellbeing, such as quality of life. Various measures, including general health-related quality of life scales and items addressing feelings of internalised stigma and perceived social support were used [28, 33, 39]. Use of scales encompassing factors related to HIV, stigma and quality of life may be more sensitive to program effects and assist with collecting consistent data [67]. Qualitative work which captures rich, thick descriptions of how programs operate to influence factors related to quality of life will contribute to valuable theorical development and empirical evidence in this area. So, too, would evaluations that consider systems level effects and types of evidence which more accurately capture the full impact of peer-based approaches, such as the influence of programs on perceived social support, health service and community engagement or HIV-related discrimination, inequities and disparities [66].

As complex social interventions we recommend that future work on peer navigation programs evaluate detailed information about peer navigators, their activities, and the quality of peer engagement. Although peer navigation programs and similar interventions for people living with HIV should be adapted and may differ significantly in their design and conceptualisation our review recommends that, at a minimum, descriptions and proposed mechanisms should incorporate the HIV status of peer navigators and any sub-characteristics or community affiliations relevant to establishing peer status with the target group. The small number of studies which did not include this information were not able provide strong justification for peer engagement or explain its relationship to program activities and effects.

Further, incorporating assessments of how different qualities of peer engagement contribute to or enhance program effects into program evaluation will also support the improvement and implementation of peer navigation programs. For example, in our study most researchers provided at least some information about the mode and duration of peer engagement, but it was only the most detailed experimental designs which considered the influence of the amount of contact on program effects. Studies which evaluated these qualities of peer engagement against study outcomes affirmed that intensive support over a relatively short period of time was required to meet initial support needs, with a more enduring need for social and emotional support and postpartum care [28, 29, 42, 43, 68]. This aligns with findings from the most recent systematic review of peer navigation programs and similar interventions, which found consistent evidence that programs providing intensive, in-person support were effective at improving HIV continuum of care outcomes [7].

Similarly, future work exploring what workplace support structures and community and clinical engagement is required for peer navigators to work most effectively would provide valuable contributions to the evidence base for successful implementation. Most studies in our review reported information about the training, support, supervision, pay and conditions available for peer navigation roles but were less frequently set up to evaluate the quality or influence of these factors on the effectiveness of programs. A common finding among studies which did consider the influence of pay and conditions was that workplaces and employment structures which provided the most stability and flexibility for navigators to meet their own health and wellbeing needs contributed to the successful delivery of programs [32, 43, 47, 52, 68]. There was also evidence that more intensive and structured supervision for peer navigators providing a range of support led to better program outcomes [47, 50].

The majority of programs investigated by studies in our review were managed or delivered in clinical healthcare settings. Challenges noted in these environments included power imbalances and a lack of organisational safety and employment frameworks for navigators to be openly recruited, identify and operate in their capacity as peers [47, 52]. Policy development and training for clinical providers to better understand the values and practices underpinning peer work was recommended by these studies as well as practice-based guidelines and standards, which further emphasise the promotion of GIPA/MIPA principals [11,12,13,14,15,16]. Notably, our review found limited evidence to inform knowledge of the strengths and challenges of program implementation led by community health organisations and how programs can be delivered in collaboration or adapted to different healthcare settings, organisations and communities. Practice-based guidelines emphasise conducting local needs assessments for both collaboration and adaptation and the importance of organisations to have strong links back to local communities of people living with HIV [11,12,13,14,15,16]. Examples of the mentorship, training and supervision and support structures that community health organisations can provide are also identified. Future research which further develops this emerging evidence base will significantly inform discussions of the scalability and implementation of peer navigation programs in diverse health systems and HIV responses.

Limitations

Our review only considered peer navigation programs operating in the current treatment cascade environment since 2015 when global targets were established. Studies conducted previously to this, particularly in the pre-ART era, are likely to consider other health outcomes. English language and the databases we consulted are also likely to have skewed our search towards studies conducted in English speaking countries, particularly the United States. We used broad search terms to capture programs similar in form and function to peer navigation services. Although peer navigation is an increasingly common way in which peer interventions for people living with HIV are conceptualised, our search may have missed programs which draw more strongly from other traditions of peer-based support and mutual aid. Similarly, our review focused on peer navigation interventions providing structured, tailored and in-person support to individuals, however, we recognise that peer support for people living with HIV can exist within many relationships and networks, and provide many benefits to individuals and communities. As we did not assess the risk of study bias, we were unable to report on the reliability of outcomes reported by studies.

Conclusions

HIV peer navigation incorporates key elements of health systems navigation as well as roles traditionally fulfilled by peers to promote the health and wellbeing of people living with HIV. Recent research provides a strong theoretical basis for peer engagement to enhance the effectiveness of health systems navigation and social support as well as evidence for the ability of peer navigation to strengthen the HIV continuum of care. However, the scope of inquiry remains limited. More research is required to capture the full impact and role that peer navigation programs may play in the detection and prevention of opportunistic infections and health promotion for non-communicable disease and quality of life concerns for people living with HIV in diverse settings, populations, implementing organisations and healthcare systems. Peer navigation programs are complex, social interventions. We recommend that future work continue to evaluate detailed information about HIV peer navigators, their activities, the quality of peer engagement as well as employment and community support structures to improve quality and impact.

Availability of data

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Brown G, O’Donnell D, Crooks L, Lake R. Mobilisation, politics, investment and constant adaptation: lessons from the Australian health-promotion response to HIV. Health Promot J Aust Off J Aust Assoc Health Promot Prof. 2014 Apr;25(1):35–41.

UNAIDS. Policy Brief The Greater Involvement of People Living with HIV (GIPA) [Internet]. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2007 Apr [cited 2020 May 25] p. 4. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2007/20070410_jc1299-policybrief-gipa_en.pdf.

Simoni JM, Nelson KM, Franks JC, Yard SS, Lehavot K. Are peer interventions for HIV efficacious? A systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2011 Nov;15(8):1589–95.

Dennis C-L. Peer support within a health care context: a concept analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2003 Mar 1;40(3):321–32.

Webel AR, Okonsky J, Trompeta J, Holzemer WL. A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Peer-Based Interventions on Health-Related Behaviors in Adults. Am J Public Health. 2010 Feb;100(2):247–53.

Simoni JM, Franks JC, Lehavot K, Yard SS. Peer Interventions to Promote Health: Conceptual Considerations. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2011 Jul;81(3):351–9.

Berg RC, Page S, Øgård-Repål A. The effectiveness of peer-support for people living with HIV: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2021 Jun;17(6):e0252623. 16.

UNAIDS Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. 2025 AIDS Targets [Internet]. Geneva: UNAIDS Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2020 [cited 2021 Nov 23]. Available from: https://aidstargets2025.unaids.org/.

Bradford JB, Coleman S, Cunningham W. HIV System Navigation: An Emerging Model to Improve HIV Care Access. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2007 Jun 1;21(s1):1–49.

Mizuno Y, Higa DH, Leighton CA, Roland KB, Deluca JB, Koenig LJ. Is HIV patient navigation associated with HIV care continuum outcomes? AIDS Lond Engl. 2018;32(17):2557–71.

Koester KA, Morewitz M, Pearson C, Weeks J, Packard R, Estes M, et al. Patient navigation facilitates medical and social services engagement among HIV-infected individuals leaving jail and returning to the community. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2014 Feb;28(2):82–90.

Farrisi D, Dietz N. Patient navigation is a client-centered approach that helps to engage people in HIV care. HIV Clin. 2013;25(1):1–3.

Broeckaert L. Practice Guidelines in Peer Navigation for People Living with HIV [Internet]. CATIE - Canadian AIDS Treatment Exchange; 2018. Available from: www.catie.ca.

National Association of People Living with HIV Australia (NAPWHA). Australian HIV Peer Support Standards [Internet]. Newtown: National Association of People Living with HIV Australia (NAPWHA); 2020 [cited 2021 Nov 19]. Available from: https://napwha.org.au/resource/australian-hiv-peer-support-standards/.

Positively UK. National Standards for Peer Support in HIV [Internet]. London; 2017 [cited 2021 Nov 19]. Available from: http://hivpeersupport.com/.

NMAC. HIV Navigation Services: A Guide to Peer and Patient Navigation Programs [Internet]. Washington DC: NMAC; 2015. Available from: www.nmac.org.

FHI360. Peer Navigation for Key Populations: Implementation Guide [Internet]. Washington DC: FHI360, LINKAGES, USAID,PEPFAR;; 2017. Available from: www.fhi360.org.

AIDS United. Best Practices for Integrating Peer Navigators into HIV Models of Care. [Internet]. Washington DC: AIDS United; 2015. Available from: www.aidsunited.org.

Genberg BL, Shangani S, Sabatino K, Rachlis B, Wachira J, Braitstein P, et al. Improving Engagement in the HIV Care Cascade: A Systematic Review of Interventions Involving People Living with HIV/AIDS as Peers. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(10):2452–63.

Boucher LM, Liddy C, Mihan A, Kendall C. Peer-led Self-management Interventions and Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy Among People Living with HIV: A Systematic Review. AIDS Behav. 2020 Apr 1;24(4):998–1022.

UNAIDS Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Fast-Track - Ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 [Internet]. Geneva: UNAIDS Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2014 [cited 2021 Nov 23]. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2014/JC2686_WAD2014report.

90-90-90. treatment target [Internet]. [cited 2022 Mar 21]. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/90-90-90.

Lazarus JV, Safreed-Harmon K, Barton SE, Costagliola D, Dedes N, del Amo Valero J, et al. Beyond viral suppression of HIV – the new quality of life frontier. BMC Med. 2016 Jun;22(1):94.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010 Dec;5(1):1–9.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005 Feb;1(1):19–32.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018 Oct;2(7):467–73. 169(.

Adams JA, Whiteman K, McGraw S. Reducing Missed Appointments for Patients With HIV: An Evidence-Based Approach. J Nurs Care Qual. 2020;35(2):165–70.

Cabral HJ, Davis-Plourde K, Sarango M, Fox J, Palmisano J, Rajabiun S. Peer Support and the HIV Continuum of Care: Results from a Multi-Site Randomized Clinical Trial in Three Urban Clinics in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2018 Aug 1;22(8):2627–39.

Cataldo F, Chiwaula L, Nkhata M, van Lettow M, Kasende F, Rosenberg NE, et al. Exploring the Experiences of Women and Health Care Workers in the Context of PMTCT Option B Plus in Malawi. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;2017(5):517–22. Apr 15;74(.

Chang LW, Nakigozi G, Billioux VG, Gray RH, Serwadda D, Quinn TC, et al. Effectiveness of peer support on care engagement and preventive care intervention utilization among pre-antiretroviral therapy, HIV-infected adults in Rakai, Uganda: a randomized trial. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(10):1742–51.

Chevrier C, Khan S, Reza-Paul S, Lorway R. ‘No one was there to care for us’: Ashodaya Samithi’s community-led care and support for people living with HIV in Mysore, India. Glob Public Health. 2016 Apr;11(4):423–36.

Cunningham WE, Weiss RE, Nakazono T, Malek MA, Shoptaw SJ, Ettner SL, et al. Effectiveness of a Peer Navigation Intervention to Sustain Viral Suppression Among HIV-Positive Men and Transgender Women Released From Jail: The LINK LA Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;01(4):542–53.

Giordano TP, Cully J, Amico KR, Davila JA, Kallen MA, Hartman C, et al. A Randomized Trial to Test a Peer Mentor Intervention to Improve Outcomes in Persons Hospitalized With HIV Infection. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2016;63(5):678–86.

Graham SM, Micheni M, Kombo B, Van Der Elst EM, Mugo PM, Kivaya E, et al. Development and pilot testing of an intervention to promote care engagement and adherence among HIV-positive Kenyan MSM. AIDS Lond Engl. 2015;29(Suppl 3(aid):8710219):S241-9.

Griffith D, Snyder J, Dell S, Nolan K, Keruly J, Agwu A. Impact of a Youth-Focused Care Model on Retention and Virologic Suppression Among Young Adults With HIV Cared for in an Adult HIV Clinic. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2019;80(2):e41–7.

Hosseinipour M, Nelson JA, Trapence C, Rutstein SE, Kasende F, Kayoyo V, et al. Viral suppression and HIV drug resistance at 6 months among women in Malawi’s Option B + program: Results from the PURE Malawi Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2017 Jun 1;75(Suppl 2):S149–55.

Karwa R, Maina M, Mercer T, Njuguna B, Wachira J, Ngetich C, et al. Leveraging peer-based support to facilitate HIV care in Kenya. PLoS Med. 2017;14(7):e1002355.

Koneru A, Jolly PE, Blakemore S, McCree R, Lisovicz NF, Aris EA, et al. Acceptance of peer navigators to reduce barriers to cervical cancer screening and treatment among women with HIV infection in Tanzania. Int J Gynaecol Obstet Off Organ Int Fed Gynaecol Obstet. 2017;138(1):53–61.

Lifson AR, Workneh S, Hailemichael A, Demisse W, Shenie T, Slater L. Implementation of a Peer HIV Community Support Worker Program in Rural Ethiopia to Promote Retention in Care. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2017 Feb 1;16(1):75–80.

Maulsby C, Positive CI, Team, Charles V, Kinsky S, Riordan M, Jain K, et al. Positive Charge: Filling the Gaps in the U.S. HIV Continuum of Care. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(11):2097–107.

Monroe A, Nakigozi G, Ddaaki W, Bazaale JM, Gray RH, Wawer MJ, et al. Qualitative insights into implementation, processes, and outcomes of a randomized trial on peer support and HIV care engagement in Rakai, Uganda. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):54.

Minick SG, May SB, Amico KR, Cully J, Davila JA, Kallen MA, et al. Participants’ perspectives on improving retention in HIV care after hospitalization: A post-study qualitative investigation of the MAPPS study. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(8):e0202917.

Myers JJ, Kang Dufour M-S, Koester KA, Morewitz M, Packard R, Monico Klein K, et al. The Effect of Patient Navigation on the Likelihood of Engagement in Clinical Care for HIV-Infected Individuals Leaving Jail. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(3):385–92.

Odiachi A, Sam-Agudu NA, Erekaha S, Isah C, Ramadhani HO, Swomen HE, et al. A mixed-methods assessment of disclosure of HIV status among expert mothers living with HIV in rural Nigeria. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(4):e0232423.

Phiri S, Tweya H, van Lettow M, Rosenberg NE, Trapence C, Kapito-Tembo A, et al. Impact of Facility- and Community-Based Peer Support Models on Maternal Uptake and Retention in Malawi’s Option B + HIV Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission Program: A 3-Arm Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial (PURE Malawi). JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017 Jun;75(1):140.

Pitpitan EV, Mittal ML, Smith LR. Perceived Need and Acceptability of a Community-Based Peer Navigator Model to Engage Key Populations in HIV Care in Tijuana, Mexico. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2020;19(101603896):1-8

Ryerson Espino SL, Precht A, Gonzalez M, Garcia I, Eastwood EA, Henderson T, et al. Implementing Peer-Based HIV Interventions in Linkage and Retention Programs: Successes and Challenges. J HIVAIDS Soc Serv. 2015 Oct;14(4):417–31.

Reback CJ, Runger D, Fletcher JB. Drug Use is Associated with Delayed Advancement Along the HIV Care Continuum Among Transgender Women of Color. AIDS Behav. 2019;25 Suppl 1(9712133):107-115.

Reback CJ, Kisler KA, Fletcher JB. A Novel Adaptation of Peer Health Navigation and Contingency Management for Advancement Along the HIV Care Continuum Among Transgender Women of Color. AIDS Behav. 2019; 25 Suppl 1 (9712133): 40-51.

Sam-Agudu NA, Ramadhani HO, Isah C, Anaba U, Erekaha S, Fan-Osuala C, et al. The Impact of Structured Mentor Mother Programs on 6-Month Postpartum Retention and Viral Suppression among HIV-Positive Women in Rural Nigeria: A Prospective Paired Cohort Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2017;75 Suppl 2(100892005):S173–81.

Sam-Agudu NA, Ramadhani HO, Isah C, Erekaha S, Fan-Osuala C, Anaba U, et al. The Impact of Structured Mentor Mother Programs on Presentation for Early Infant Diagnosis Testing in Rural North-Central Nigeria: A Prospective Paired Cohort Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2017;75 Suppl 2(100892005):S182–9.

Sam-Agudu NA, Odiachi A, Bathnna MJ, Ekwueme CN, Nwanne G, Iwu EN, et al. “They do not see us as one of them”: a qualitative exploration of mentor mothers’ working relationships with healthcare workers in rural North-Central Nigeria. Hum Resour Health. 2018;16(1):47.

Steward WT, Sumitani J, Moran ME, Ratlhagana M-J, Morris JL, Isidoro L, et al. Engaging HIV-positive clients in care: acceptability and mechanisms of action of a peer navigation program in South Africa. AIDS Care. 2018;30(3):330–7.

Dutcher MV, Phicil SN, Goldenkranz SB, Rajabiun S, Franks J, Loscher BS, et al. “Positive Examples”: a bottom-up approach to identifying best practices in HIV care and treatment based on the experiences of peer educators. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2011;25(7):403–11.

Peterson JL, Rintamaki LS, Brashers DE, Goldsmith DJ, Neidig JL. The Forms and Functions of Peer Social Support for People Living With HIV. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2012 Jul 1;23(4):294–305.

Fisher WA, Fisher JD, Harman J. The Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills Model: A General Social Psychological Approach to Understanding and Promoting Health Behavior. In: Social Psychological Foundations of Health and Illness [Internet]. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2003 [cited 2021 Nov 25]. p. 82–106. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470753552.ch4.

Heaney C, Israel BA. Social Networks and Social Supports. In: Karen Glanz, Barbara K. Rimer, K. Viswanath, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice [Internet]. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008 [cited 2021 Nov 16]. Available from: http://ez.library.latrobe.edu.au/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=238450&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

Cohen S, Syme SL, editors. Social support and health. Orlando: Academic Press; 1985. 390 p.

Kahn R, Antonucci T. Convoys Over the Life Course: Attachment Roles and Social Support. In: Life Span Development. 1980. p. 253–67.

Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, US: Prentice-Hall, Inc; 1986. xiii, 617 p. (Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory).

Parker R, Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: a conceptual framework and implications for action. Soc Sci Med. 2003 Jul;1(1):13–24. 57.

Saleebey D. The strengths perspective in social work practice. Boston: Pearson; 2013.

Montales MT, Chaudhury A, Beebe A, Patil S, Patil N. HIV-Associated TB Syndemic: A Growing Clinical Challenge Worldwide. Front Public Health. 2015;3:281.

Rajasingham R, Smith RM, Park BJ, Jarvis JN, Govender NP, Chiller TM, et al. Global burden of disease of HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis: an updated analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017 Aug;17(8):873–81.

Khalpey Z, Fitzgerald L, Howard C, Istiko SN, Dean J, Mutch A. Peer navigators’ role in supporting people living with human immunodeficiency virus in Australia: Qualitative exploration of general practitioners’ perspectives. Health Soc Care Community [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 Aug 3];n/a(n/a). Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13465.

Brown G, Reeders D, Cogle A, Madden A, Kim J, O’Donnell D A Systems Thinking Approach to Understanding and Demonstrating the Role of Peer-Led Programs and Leadership in the Response to HIV and Hepatitis C: Findings From the W3 Project. Front Public Health [Internet]. 2018 Aug 31 [cited 2019 Oct 24];6. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6127267/.

Brown G, Mikołajczak G, Lyons A, Power J, Drummond F, Cogle A, et al. Development and validation of PozQoL: a scale to assess quality of life of PLHIV. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2018 Apr 20 [cited 2020 May 22];18. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5910603/.

Myers JJ, Koester KA, Kang Dufour M-S, Jordan AO, Cruzado-Quinone J, Riker A. Patient navigators effectively support HIV-infected individuals returning to the community from jail settings. Int J Prison Health. 2017;13(3–4):213–8.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank La Trobe University Library research support staff for their assistance with developing database search strategies.

Funding

This research was conducted towards obtaining a Doctor of Philosophy degree from La Trobe University, supported by a research grant from ViiV Healthcare. The funder played no role in the design or conduct of the review.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors conceived of the original idea. TK developed study design under supervision of GB and AB. TK and GB screened search results, and all authors refined search strategy and inclusion criteria. TK conducted analysis and wrote the manuscript with supervision and feedback from AB and GB.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

This research is conducted by TK in the course of obtaining a Doctor of Philosophy degree from La Trobe University.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Krulic, T., Brown, G. & Bourne, A. A Scoping Review of Peer Navigation Programs for People Living with HIV: Form, Function and Effects. AIDS Behav 26, 4034–4054 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-022-03729-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-022-03729-y