Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has great potential to disrupt the lives of persons living with HIV (PLWH). The present convergent parallel design mixed-methods study explored the early effects of COVID-19 on African American/Black or Latino (AABL) long-term survivors of HIV in a pandemic epicenter, New York City. A total of 96 AABL PLWH were recruited from a larger study of PLWH with non-suppressed HIV viral load. They engaged in structured assessments focused on knowledge, testing, trust in information sources, and potential emotional, social, and behavioral impacts. Twenty-six of these participants were randomly selected for in-depth semi-structured interviews. Participants were mostly men (64%), African American/Black (75%), and had lived with HIV for 17 years, on average (SD=9 years). Quantitative results revealed high levels of concern about and the adoption of recommended COVID-19 prevention recommendations. HIV care visits were commonly canceled but, overall, engagement in HIV care and antiretroviral therapy use were not seriously disrupted. Trust in local sources of information was higher than trust in various federal sources. Qualitative findings complemented and enriched quantitative results and provided a multifaceted description of both risk factors (e.g., phones/internet access were inadequate for some forms of telehealth) and resilience (e.g., “hustling” for food supplies). Participants drew a direct line between structural racism and the disproportional adverse effects of COVID-19 on communities of color, and their knowledge gleaned from the HIV pandemic was applied to COVID-19. Implications for future crisis preparedness are provided, including how the National HIV/AIDS Strategy can serve as a model to prevent COVID-19 from becoming another pandemic of the poor.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past decade, rates of engagement along the HIV care continuum have improved significantly in the United States [1]. Yet, a substantial proportion of persons living with HIV (PLWH) faces serious challenges to such engagement [1]. Among PLWH, those from African American or Black and Latino (AABL) and low-socioeconomic status (SES) backgrounds are over-represented compared to their proportions in the general population [2]. However, AABL PLWH are also more likely to experience impediments to HIV care and persistent antiretroviral therapy (ART) use, and to have greater morbidity and earlier mortality, compared to their White and more socioeconomically advantaged peers [3]. The present study focuses on AABL long-term survivors of HIV from low-SES backgrounds with serious barriers to engagement along the HIV care continuum in New York City (NYC).

In March 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) highlighted PLWH as a population that may be at heightened risk for severe physical health outcomes due to COVID-19 compared to the general population [4]. The first case of COVID-19 in New York State was confirmed on March 1, 2020 [5]. NYC quickly became an epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic, where both incident cases and deaths from COVID-19 increased exponentially [6]. On March 22, 2020, non-essential businesses were closed [7] and members of the non-essential workforce (that is, those not engaged in maintaining the safety, sanitation, and vital operations of residences, commercial businesses, and public institutions) were ordered to engage in physical distancing; that is, keeping space between oneself and other people when outside of the home. NYC citizens who were not essential workers were asked to remain indoors with some exceptions, such as to obtain groceries, medicine, or to exercise [7]. Other recommendations included the use of facial coverings when in public [8]. Although outpatient health care facilities were considered essential, widespread disruptions to health care were reported [9, 10]. Many HIV care and mental health treatment settings eventually switched to a telehealth platform but some substance treatments/supports such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Narcotics Anonymous (NA) were put on hold [11]. Overall, this period was a time of rapid change in how mental and physical health and pharmacy services were provided to PLWH [12]. By April 2020, New York had more confirmed cases of COVID-19 than any other country in the world besides the United States as a whole [6]. As of September 3, 2020, there had been 235,435 confirmed cases and 11,282 confirmed deaths associated with COVID-19 in NYC [13]. Moreover, long-standing systemic health and social inequities put people from AABL racial/ethnic groups at increased risk of contracting and dying from COVID-19 compared to White populations [2]. As of September 3, 2020, 62% of those who died from COVID-19 in NYC were AABL [14].

On May 25, 2020, George Floyd, a 46-year-old Black man, was killed in Minneapolis, Minnesota [15]. Floyd's death triggered a series of protests against police brutality, lack of police accountability, and the larger, ongoing, and systemic problem of structural racism, including in NYC where such protests, including those led by the Black Lives Matter movement, were frequent and highly visible [15]. Thus, the movement for racial justice consolidated and became more prominent concurrent with marked racial/ethnic disparities in COVID-19 deaths. Together, the movement for racial justice and racial/ethnic disparities in COVID-19 incidence, morbidity, and mortality served as the context for the present study.

The existing literature on COVID-19 among PLWH to date has focused primarily on incidence studies [16], clinical studies [17], and case reports from the field [18]. Overall, knowledge from previous coronavirus outbreaks on the susceptibility and severity of disease in PLWH was scarce in these early stages of the pandemic [19]. However, as Pinto and Park (2020) noted, COVID-19 has great potential to disrupt the HIV continuum of care and prevention [12], raising concerns that PLWH would be seriously adversely affected. On the other hand, PLWH may have some advantages in coping with the COVID-19 pandemic compared to the general population. For example, the experience of living with HIV may provide PLWH with intimate knowledge of pandemics and their effects, and expertise in managing life in the context of pandemics, that others lack. These lessons gleaned from living with HIV could include understanding the importance of behavior change and adaptation in response to the pandemic, the dynamics of stigma and how to cope with it, the ways public health becomes politicized, and promises of vaccines [20]. Yet, at the same time, new pandemics necessitate the interpretation of epidemiological, medical, and prevention-related information in a rapidly evolving context. For AABL PLWH, the interpretation of such information may be shaped and/or complicated by distrust of medical systems and information. Indeed, such distrust is common among AABL PLWH from low-SES backgrounds [21], similar to other AABL populations, largely as a function of being located in a society characterized by structural racism [22] and also related to numerous past abuses of AABL populations in medical research and settings [23]. Yet, while medical distrust is common, it does not preclude engagement with health care systems and, in fact, commonly co-occurs with the use of ART and engagement in HIV care among AABL PLWH [24]. However, because the evolving COVID-19 pandemic requires rapid communication of health and prevention-related information, and the content of these communications changed over time, it is possible medical distrust could impede or affect how COVID-related information was taken up by AABL PLWH.

The objective of the present study was to uncover and explore how this subpopulation of PLWH; namely, AABL long-term survivors of HIV from low-SES backgrounds, understood and adapted to COVID-19 in the early stages of the pandemic in a major COVID-19 epicenter. We attended to sources of risk, adverse effects, the role of medical distrust, and resilience. In particular, we sought to document adaptation and coping strategies, as well as gaps that remain, all of which could be used to inform public health system preparedness for future public health crises. This is a descriptive and exploratory study, and thus, we do not present formal hypotheses. Yet, guided by Shiau and colleagues [25], we anticipated that the same social and structural determinants of health that put AABL PLWH at risk for co-morbidities and other poor outcomes while living with HIV would heighten the likelihood of adverse outcomes as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., poverty, transportation access, racial segregation, food insecurity, and social isolation) [26]. In particular, we explored the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on AABL PLWH’s engagement in HIV care and ART adherence, mental health, substance use patterns, and general wellbeing, including related to community-wide prevention measures such as stay-at-home orders that had great potential to negatively affect this subpopulation of PLWH.

Methods

Summary of the Present Study

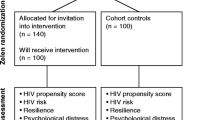

The present was cross-sectional and descriptive and used a convergent parallel mixed-methods design [27]. It was grounded in a multi-level social-cognitive theoretical perspective called the theory of triadic influence that highlights individual-, social-, and structural-level influences on behavior [28], along with critical race theory [29], in that the perspectives of AABL individuals were centered and structural racism was considered as a potential contributing factor in the processes and outcomes under study. It drew upon a brief structured assessment battery and semi-structured in-depth qualitative interviews focused on the effects of the new coronavirus (also called SARS-CoV-2) conducted between April 16, 2020 and August 7, 2020 in NYC. Participants were AABL PLWH from low-SES backgrounds (N = 96) recruited from an ongoing larger study. The larger study was an intervention optimization trial grounded in the multiphase optimization strategy (MOST) framework designed to test intervention components addressing barriers to engagement along the HIV care continuum. The larger study’s procedures are described in detail elsewhere [30]. The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the New York University School of Medicine and participants gave informed consent for study activities.

Eligibility Criteria for the Larger Study

The larger study’s inclusion criteria were: (1) age 18–65 years; (2) African American or Black or Latino race/ethnicity; (3) HIV diagnosed for > 6 months (HIV status medically confirmed); (4) ART adherence less than 50% in the past six weeks and detectable HIV viral load based on laboratory report; (5) sub-optimal engagement in HIV care (operationalized as less than one visit in every four-month period in the past year [two of them at least 90 days apart] or > two missed visits without prior cancellation in the past year; (6) resides in the NYC metropolitan area; and (7) able to conduct research activities in English or Spanish.

Procedures

We recruited participants who had not yet completed the larger study (N= 274 were eligible for the present study out of 512 enrolled in the larger study). Participants were contacted by phone during the study period and asked if they would be interested in participating in a brief (20 minute) interview on their perspectives on the new coronavirus and COVID-19. Those who agreed provided verbal consent following an IRB-approved script. The interview was then conducted over the phone by a staff member using a computer-assisted personal interviewing format. A total of 96 participants were enrolled. From the 96 enrolled participants, 35 were randomly selected for the qualitative in-depth interview. These individuals were contacted by a second staff person, queried about participation, and verbal informed consent was obtained. A total of 26 engaged in an in-depth interview. In-depth interviews were conducted over the phone, lasted approximately 40-60 minutes, and were audio-recorded. Audio-recordings were professionally transcribed verbatim for analysis. No participants declined either the quantitative/structured or the qualitative interview. Participants received $20 compensation for the structured interview and $25 for the qualitative interview. Compensation was provided on the same day as the interview using the Greenphire ClinCard system, a refillable debit card.

Measures

Socio-Demographic, Background, and HIV-Related Health Characteristics

Using a structured instrument developed for populations in high-risk contexts [31], we assessed age, sex, sexual and/or gender minority status (yes/no), race/ethnicity, employment status (working full-time or part-time on- or off-the-books in the past three months), whether the participant ran out of money for basic necessities like rent, utilities or food at least monthly or more often in the past year, an indication of extreme poverty, and stable housing in the past three months (has his/her/their own home or apartment, including one funded by government programs or benefits, in contrast to temporary placements such as single-room occupancy residences or shelters). Years since HIV diagnosis was assessed [32]. HIV viral load at enrollment was assessed by a professional laboratory and is presented as a log10 transformation. Food insecurity over the past year was assessed with a three-item measure (I worried whether my food would run out before I got money to buy more, the food that I bought just didn't last and I didn't have money to get more; and I couldn't afford to eat balanced meals) using a three-point scale (never true, sometimes true, often true). Food insecurity was coded as present if the quality, quantity, or consistency of food was insufficient “sometimes” or “often” in the past year [33].

COVID-19 knowledge, testing experiences, and concerns

Knowledge, testing experiences, and concerns about the new coronavirus were assessed with a version of a structured instrument developed by Kalichman (Kalichman, unpublished measure, April 2020). We assessed domains such as whether participants had heard of the new coronavirus, whether they had heard some to a great deal about the new coronavirus, testing issues (attempts to be tested, test received, tested in their HIV clinic, whether diagnosed, friends and family diagnosed), and level of concern about the participant or someone he/she/they know “catching the new coronavirus” on a 0 to 100 scale. Because we present single items and do not create scale scores for this or other subsections of the measure, coefficients of internal reliability were not calculated.

COVID-19/Coronavirus Responses and Effects

Using a 13-item version of the structured instrument developed by Kalichman (Kalichman, unpublished measure, April 2020) we asked about the effects of the new coronavirus, coded on a three-point scale (no; yes, a little; yes, a lot). Questions included: staying indoors and away from public places, canceled plans that involved other people, been unable to get the food you need, been unable to get to a pharmacy, been unable to get the medicine you need, you asked others to stay away to avoid getting the new coronavirus, you have been asked by others to stay away, you were told not to come to work/school, you avoided public transportation, you canceled a clinic/doctor’s appointment, a clinic or health care professional canceled an appointment, substance use treatment such as AA/NA was canceled, and a social worker/social service provider canceled. Items were re-coded as 0) no or yes a little vs. 1) yes, a lot.

Emotional/Behavioral Experiences and Stress Related to the New Coronavirus

Using a version of the Pandemic Stress Index [18], we assessed 21 potential emotional, social, and behavioral effects related to the new coronavirus rated on a yes/no scale, such as worry, stigma, and discrimination; financial loss; increases or decreases in substance use; decreased ability to obtain substances; confusion about the new coronavirus; increases or decreases in sexual activity; and feeling that one was contributing to the greater good by preventing oneself or others from contracting coronavirus.

Trust in Government Agencies

Participants were asked six items regarding how much they trusted that a source of health information or public health guidance was “doing all it can to prevent the spread of the new coronavirus” on a four-point Likert-type scale (do not trust at all, slightly trust, somewhat trust, and trust completely). Participants were queried about trust in the local New York State government; the local NYC government; the federal government, including the President and Congress. Regarding information about the new coronavirus, we asked about trust in information from the CDC; the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; and information found online or on social media (Kalichman, unpublished measure, April 2020)

Effects of the New Coronavirus on HIV Management

Using three items and a yes/no scale, we asked participants whether they had been taking HIV medications over the past three months and if yes, whether they stopped or increased taking HIV medications because of the new coronavirus. Using two items and a four-point scale (not at all, a little, somewhat, a great deal) we assessed how much the new coronavirus increased willingness or desire to take HIV medication with a high level of adherence and got in the way of how often the participant took ART, recoded as 0) no (not at all to a little) and 1) yes (somewhat to a great deal).

Phone/Internet Access, Coping Strategies, and Gaps that Remain

We asked five open-ended questions as part of the quantitative survey: (1) Is your phone or computer access good enough during this time of the new coronavirus? Please explain; (2) Can you think of ways that you or others in the community have come up with to manage in the time of the new coronavirus?; (3) What do you and members of your community need to manage life during the coronavirus outbreak that you are not getting?; (4) Is there anything else we should know about how the coronavirus is affecting how you manage your HIV-related health care and medications?; and (5) Is there anything else we should know about how the coronavirus is affecting any other aspect of your life? Your neighborhood? The community of persons living with HIV? Responses were treated as qualitative data, coded, and summarized.

Qualitative Interview Guide

In-depth interviews followed a semi-structured interview guide collectively developed by the research team and grounded in a multi-level theoretical perspective that highlighted individual-, social-, and structural-level influences on behavior, along with critical race theory, as described above [28, 29]. The interview guide included a series of questions and prompts to uncover and explore participants’ knowledge of, experiences with, and perspectives on the new coronavirus and its effects, including perspectives on how COVID-19 affects PLWH, effects on substance use patterns, coping strategies, and unmet needs. The guide included many of the same domains as the quantitative measure but took a semi-structured approach to elicit and probe the perspectives and experiences of participants in the study. The guide started with general open-ended questions, such as “What have you heard about the new coronavirus, also called COVID-19 or SARS-CoV-2?” “Who or where do you get your information from? What do you think about the accuracy of what you have heard?” and “What sources of information do you trust and why?” Questions about PLWH included “Do you think PLWH are more at risk or less at risk for the new coronavirus than people not living with HIV?” Questions about coping included “Can you think of ways that you or others in the community have come up with to manage in the time of the coronavirus?” We explored the effects of the new coronavirus on health behavior with items such as “Has the new coronavirus affected your desire or ability to access HIV health care? Has it affected your desire or ability to access other types of health care, including health care for conditions other than HIV? Mental health care?” Regarding perspectives on racial/ethnic and SES-related disparities, we asked and explored, “Do you think people of color are more at risk or less at risk for the new coronavirus than White people?” and “Do you think people with limited means are more at risk or less at risk for the new coronavirus than people with high income, resources, and means?” The guide concluded with some general questions to ensure we captured participants’ perspectives on and experiences with COVID-19 comprehensively.

Data Analyses

Consistent with the convergent parallel mixed-methods design, we carried out analyses of quantitative and qualitative data at the same time and then compared, contrasted, and integrated the results from the two sets of analyses [27]. In quantitative analyses, we used descriptive statistics and measures of central tendency where appropriate to summarize socio-demographic characteristics and years living with HIV; knowledge, testing experiences, and concerns; coronavirus responses and effects; emotional and behavioral experiences related to the new coronavirus; trust in government agencies; and effects of the coronavirus on HIV management. The qualitative data analysis strategy followed a directed content analysis approach that was both inductive and theory-driven [34, 35]. First, a primary researcher trained in anthropology analyzed interview transcripts and developed an initial start-code list drawn from the interview guide and informed by the theory of triadic influence and critical race theory, as described above. Next, a second trained medical anthropologist coded a subset of the interview transcripts and met frequently with the primary data analyst. Codes were again refined, and discrepancies between the two analysts were resolved by consensus. Findings from this initial round of coding were then presented to the larger research team, which formed an interpretive community [36] and codes were refined again. Then, codes were combined into larger themes in an iterative process in collaboration with the interpretive community. In addition to the transcripts of the in-depth interviews, data from the five open-ended questions included in the quantitative assessment were coded and combined into themes and included in the results in a separate section where non-redundant themes were found. Regarding positionality and methodological rigor, the research team was made up of men and women from White, Latino, Black, and Asian backgrounds. The primary and secondary data analysts were experienced with HIV research, including with this subpopulation of PLWH. Positionality challenges related to sex, gender, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, power, health, SES, and privilege were intentionally addressed throughout the data collection and analysis process through reflection and training, which focused on how these types of issues might impact the interviewing process/data collection and data analysis [37, 38]. Methodological rigor of the analysis was maintained through an audit trail of process and analytic memos and periodic debriefing with the larger research team, which included experts in long-term HIV survivorship and structural racism [39].

Data Integration

First, the interpretive community assessed concordance between the quantitative results and the primary themes in the qualitative data. To do so, we used an informational matrix [27, 40] to compare the quantitative and qualitative results at a granular level (quantitative section by section compared to themes) and examine areas of convergence and divergence. The primary results were summarized.

Results

As shown in Table 1, participants ranged in age between 25 and 63 years, and were 47 years old, on average (SD = 10 years). Approximately two-thirds were men (63%) and half (52%) were sexual/gender minorities. A total of 75% were African American or Black, and the remainder were Latino. Only 8% were employed, and 43% ran out of funds for necessities monthly or more in the past year, an indication of extreme poverty. Most (84%) met the criteria for food insecurity. Half had stable housing (52%) and the remainder lived in temporary housing situations, shelters, or in locations not intended for habitation (e.g., parks). Participants had been diagnosed with HIV between 0 and 30 years ago, with an average length of time since HIV diagnosis of 17 years (SD = 9 years). The average log10 transformed HIV viral load at enrollment was 3 (SD = 1). The sociodemographic and other characteristics of the subset randomly selected for qualitative interviews did not differ from those of the sample as a whole.

Quantitative Results

All participants had heard of the new coronavirus, as shown in Table 2, and almost all (97%) had heard a substantial amount about it. A substantial proportion (44%) believed they likely needed a test for the new coronavirus, tried to obtain a test (41%), and approximately one-third had received a test (35%), usually at the same site where HIV care was received (33%). Rates of diagnosis with COVID-19 were low in this early stage of the epidemic (2%), although 40% reported friends or family members had been diagnosed with COVID-19.

Knowledge and concerns about the new coronavirus, and testing experiences, are presented in Table 3. On a 0–100 scale, the mean level of concern regarding catching the new coronavirus was 75 (SD = 34), and similarly, 79 (SD = 32) regarding “someone you know” catching the new coronavirus. The most common effects of the new coronavirus were staying indoors and away from public places (80%), canceling plans that involved other people (74%), having a medical clinic or physical health care professional close or cancel an appointment (70%), a social worker or social service provider closing or canceling an appointment (60%), and asking others to stay away (56%). Conversely, effects such as being unable to get food (15%), to a pharmacy (14%), or needed medicine (9%) were relatively uncommon.

Regarding emotional/behavioral experiences and stress related to the new coronavirus (Table 3), the most common effects, positive or negative, or stressors included: feeling that you were contributing to the greater good by preventing yourself or others from getting coronavirus (92%), worrying about friends, family, partners (83%), frustration or boredom (80%), getting emotional or social support from family, friends, partners, a counselor, or someone else (80%), changes to the normal sleep pattern (78%), increased anxiety (70%), loneliness (67%), getting financial support from family, friends, partners, an organization, or someone else (57%), increased depression (56%), personal financial loss (54%), and a decrease in sexual activity (44%). Other effects such as not having basic supplies (e.g., food, water), confusion about the coronavirus, increased or decreased alcohol or other substance use and/or the ability to obtain substances, stigma or discrimination, and increased sexual activity were less common.

Trust in the information provided by various government agencies is presented in Table 4. The local NYC government was the most trusted agency (66% trusted somewhat to completely), followed by the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (66%), New York State government (65%), the CDC (64%), and social media (43%). Trust in the federal government, including the U.S. President and Congress, was low (27%).

With regards to effects on recent HIV medication use (Table 4), almost all participants (90%) were taking ART at the time of the interview. Very few (2%) decided to stop taking ART because of the coronavirus, and 40% reported how often they took ART increased because of the coronavirus. Approximately half (56%) reported coronavirus increased their willingness or desire to take ART with a high level of adherence. A minority reported coronavirus got in the way of how often they actually took ART (22%).

Results from Open-Ended Questions Included in the Quantitative Interview

In response to the question “Is your phone or computer access good enough during this time of the new coronavirus?” we found almost all participants had some phone access, including “Obama phones;” that is, phones provided by the Lifeline Free Cell Phone Program, which may include internet access depending on participants’ specific service plans. Others had smartphones with internet access. Obama phones were considered vital but commonly of poor quality. Those who did not have phones were often individuals located in homeless shelters, suggesting extreme poverty precluded phone access. Participants commonly expressed a desire for access to computers, but also a lack of computer skills. Some typically accessed computers through libraries, but these facilities were closed due to the pandemic. Internet access was vital for participants with children in school, as the school system moved to remote instruction. Overall, participants had access to basic phone service, but access to computers and to the internet were less common. Representative responses to this item included:

I have an Obama phone. It’s not durable, so I have communication problems.

They (the Lifeline Program) have extended the plan to provide unlimited talk and text and upped the limit for the internet access on the phone for free (to meet clients’ needs during the pandemic).

I have no money to pay bills, but my internet hasn't been cut yet.

(I have) some issues with the internet, and I was unable to access some doctor appointments because I do not have WIFI.

I have been having a hard time getting internet and I really want a laptop, but I do not have one now.

I don't have money to pay for internet on my phone. I usually use computers in the library, so I currently don't have computer access.

Yes, I have a good phone service. I have WIFI that the kids use for remote learning (when public schools moved to an online format).

We asked, “Can you think of ways that you or others in the community have come up with to manage in the time of the new coronavirus?” Participants described ways they coped with anxiety, boredom, and social isolation. “Keeping busy” was a common theme that included examples such as moving “hangouts” and conversations with friends online; reading, watching television and movies; journaling; getting to know one’s neighbors; learning to cook; trying new recipes; exercising (including exercising in the house); engaging in religious or spiritual practices such as prayer or meditation; volunteering at food pantries; helping neighbors; providing health information to others; starting arts and crafts projects; initiating online education classes; and handling substance use issues (e.g., “AA meetings outdoors,” “I have been talking to my parents about my increased substance use since I had lost control over substance use, but I regained my mental consciousness over it”). Managing health care needs was time-consuming (e.g., “I had to reach out to several different people in the clinic and at the pharmacy to figure out my medication refills and delivery.”) Participants found creative ways to stay in touch with friends, loved ones, health care providers, therapists, and other community members and this was vital to many participants. Perhaps most importantly, participants noted that adopting COVID-19 prevention strategies such as practicing social distancing, staying indoors, wearing face coverings, and washing one’s hands frequently were effective ways of coping with COVID-19 related anxieties. Representative quotes included:

I am more into family, trying out new recipes, trying to take care of myself more. Taking more baths, working on my spiritual life, lots more prayer. I talk to family on the phone a lot more.

I am wearing a mask and using hand sanitizer. Most of my doctor appointments have been telehealth. I have managed to stay “clean” from drugs during this time. I got cable TV and I am very happy to have that to hold my attention.

Not letting it [get into my] head, the paranoia or fear. Being mindful that there are other people in that state of mind. I am keeping a respectful distance to dealing with others. But trying to not let it limit me.

In response to the question “Is there anything else we should know about how the coronavirus is affecting any other aspect of your life? Your neighborhood? The community of persons living with HIV?” we found that many participants expressed concerns that neighbors, coworkers, community members, and the public, in general, were failing to take COVID-19 seriously enough, particularly regarding physical distancing and wearing a face covering. These participants describe feeling extreme anxiety, with one referring to himself as “a nervous wreck.” Participants who had been employed before the outbreak of COVID-19 also commonly reported a reduction in hours or job loss, and therefore, reduced wages. Several participants also noted that the changes that have come about due to COVID-19 impacted all aspects of life. Representative answers included:

It's just annoying that people aren't taking this seriously and aren't being safe and are getting sick. I just don't want to end up getting anything because of them.

I always say that being poor is a predicament, it's not a lifestyle or shouldn't be. However, that is not a belief system and a lot of people believe that if I'm poor I don't need to educate myself on how I take care of this disease around or with me or whatever. So, they do nothing and they don't inform themselves. They have a very disposable and dismissive attitude about maintaining any form of education and empowerment so they glide along and that is the saddest thing I can say dealing with this. And you see it in their behavior if you pass a community park on the way to a grocery store that isn't closed and you see people playing basketball or soccer those activities that is doing everything that has nothing to do with distancing, and doing the opposite.

Overview of Qualitative Results from in-Depth Interviews

The present study took place in the early months of the COVID-19 epidemic in one of the epicenters of the pandemic. Overall, participants expressed fears and anxieties associated with COVID-19, and they certainly worried about contracting the new coronavirus. Moreover, they were concerned about being at higher risk for complications from COVID-19 due to living with HIV. We found participants experienced the enormity of the challenges inherent in living with HIV while facing risks from COVID-19, combined with structural and other forms of racism so apparent in the larger society. Further, we found participants viewed and reacted to COVID-19 through the lens of living with HIV over a long period and from a position of low-SES. Participants’ knowledge of the HIV pandemic and the evolution of ART often factored into their evaluation of the risks inherent in COVID-19, which they saw as a serious threat, particularly in the context of living with HIV, a lack of treatment for COVID-19, and the length of time it might take to develop effective treatments for COVID-19, as they had seen with HIV. At the same time, they marshaled skills developed from their past experiences with living with HIV, and knowledge developed as a function of living at the lowest end of the SES continuum, to make sense of and adapt to the changing realities of the COVID-19 pandemic. These adaptations included “hustling” to meet material needs in rapidly evolving and confusing circumstances, and coping with the effects of physical distancing, the shutdown of non-essential services, and the shift in service systems to a virtual format. Thus, although this was a challenging and uncertain time for participants, they displayed various coping and survival skills throughout their interviews. We found they were already adept at connecting to systems of support and that they built on these skills to adapt to COVID-19. As noted above, this adaptation to COVID-19 took place within the context of a national reckoning with police brutality and the reemergence and consolidation of a racial justice movement. The intersection of these national events with COVID-19 increased stress and challenges for participants. Yet, resilience was evident as they drew on their existing skillsets developed as both long-term survivors of HIV and from living at the lower end of the socio-economic strata.

Participants’ descriptions of perspectives on and experiences with COVID-19 were organized into six broad themes: general knowledge, information sources and trust/distrust, COVID-19 disparities, basic needs, stress and coping with fears and concerns, and changes in individual HIV- and health-related behavior (ART use, HIV primary care, and other needed services such as treatment and support for mental health and substance use concerns including AA and NA). We describe these six themes in more detail below and present a summary in Fig. 1. Names used below are pseudonyms and identifying details were changed or eliminated to protect participants’ confidentiality.

General Knowledge

Despite the high degree of uncertainty surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic at the time of the interviews, participants were generally knowledgeable about important aspects of the COVID-19 outbreak. They frequently noted that the virus was understood to have originated in Asia, it is often transmitted through close contact with infected people via droplets, COVID-19 infection is sometimes asymptomatic, and that COVID-19 symptoms included cough, shortness of breath, fever, fatigue, and loss of a sense of taste and/or smell. Participants were also aware that at the time of the interviews that the most highly recommended prevention methods were physical distancing, face coverings, and handwashing. For example, Jordan was a 50-year-old Black man who had been living with HIV for 26 years:

What I been hearing is that it’s some type of virus that comes from, I believe Asia, South Asia, something like that. And not sure how they spread it, I'm not sure about that part, but it’s like you’ve got to be totally, you call it, your hands got to be washed all the time, have to keep your face covered, you’ve got to watch out for people who got cough or—it’s like you have a cold, some people have cold symptoms and that’s one of the symptoms that says you may have it. It worries me a lot because little things like if you cough, you might have it, if you sneeze too much, you might have it, if you’re around too many people, you might have it.

When asked about living with HIV while facing the risk of contracting COVID-19, the majority of those interviewed spoke about the fear of increased risk among PLWH of experiencing the more serious COVID-related illnesses compared to those not living with HIV. Arturo, a 38-year-old Latino man who had lived with HIV for nine years, noted the following:

Well, the ones that I’ve listened to have stated that individuals with a compromised immune system, the elderly, or individuals that have underlying health issues are the ones that are most at risk from COVID. [...] I’m in a category, yes, you know that’s where the anxiety comes in and [I’m] just analyzing everything. That puts things into a perspective.

Lastly, participants overall were well aware of prevention measures such as physical distancing, washing one’s hands with soap and water for a minimum of 20 s, using hand sanitizer where available, using face coverings, and avoiding touching one’s face. They understood that not everyone who was infected with COVID-19 will experience symptoms. Further, having lived with HIV for an extended amount of time sharpened skills for filtering key health messages from a variety of sources, along with knowledge of systemic and structural racism and inequities, as we describe in the next section.

Information Sources and Trust/Distrust

Participants received their COVID-19-related information from a combination of sources including local and national cable television news, social media, and word-of-mouth. They also obtained information about COVID-19 from radio broadcasts, late-night talk shows, workplaces, support groups, and healthcare providers. Despite feeling comfortable with the basic facts about COVID-19, many participants expressed the need for at least a moderate degree of skepticism when it came to information related to COVID-19 and recalled taking much of what they had heard “with a grain of salt.” Brenda, a 36-year-old Black woman who had lived with HIV for nine years, noted that she would prefer more direct evidence before completely trusting secondhand information:

I heard [about COVID-19] over the news. Like on something that I read on social media, on Facebook. They say that heat kills it, yeah. I don't know if it's true, you know? I don't know if it's true or not. But that's what I heard. Sometimes I believe the stuff and sometimes I just, you know, I don't think it's true. Until I can see that it happened, you know?

Participants found value in not taking information at face value and described being careful about information sources (e.g., trusting information from relatives over social media posts). The majority of participants reported finding the information provided by local and state officials to be significantly more trustworthy than that provided by federal authorities, with several participants even suggesting that the federal government’s response to COVID-19 was negligent to the point of being malevolent. Rodney, a 59-year-old Black man who had been living with HIV for 25 years, stated:

Well, I just think for whatever reason, I don’t know who’s who, but I just feel a little bit more comfortable listening to Cuomo [the governor of New York] than the White House. [...] I'm very skeptical about the federal government, I really don’t trust [them] especially when you’re dealing with people of color anyway, their record is not that good. Because the first thing that comes to my mind is the Tuskegee experiment that they had, you know what I'm saying? I'm a Black man. The federal government is not high up on the list [of trustworthy sources]. That’s part of the history of this country, you know what I'm saying?

Participants had well-developed views about where to access information about COVID-19, evaluated sources thoughtfully and critically, and were well informed, especially about prevention strategies. Some displayed a wariness of information sources, particularly at the federal level, and questioned their content. For these participants, skepticism was a safety strategy created from an awareness of anti-Black racism and maltreatment of Black and other populations of color by federal agencies and health care settings, with the Tuskegee Syphilis Study being one of the most infamous and egregious historical examples of such maltreatment [23].

Perspectives on COVID-19 Disparities

Participants’ knowledge about COVID-19 also generally included an awareness of how the pandemic had disproportionately affected AABL populations, although views on this were not universal. When asked whether they believed that people from racial or ethnic minority group backgrounds were differentially affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, many participants responded in the negative, often making statements closely resembling the popular 1980s messaging stating that, like HIV, the new coronavirus “doesn’t discriminate.” Others, however, were adamant that, as has happened in the past, AABL populations had been more negatively affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, with some participants making explicit connections to racial/ethnic disparities in COVID-19 morbidity and mortality rates and recent protests following the killings of Black men and women at the hands of police (George Floyd, Breonna Taylor), by White men in the South (Ahmaud Arbery), and others. As Marion, a 63-year-old Black man who had been living with HIV for almost 20 years, noted:

Oh, I mean it’s just being Black. It’s not the first time it’s happened and it won’t be the last. […] I mean I can’t even count the number of Black people that’s been killed by cops. [...] Aubrey, the kid that was jogging that go into these lady’s houses, you know by – with no-knock warrants, shooting them up and whatnot. But this guy, can’t breathe, you know when I first saw that video I really couldn’t believe it, the guy’s saying I can’t breathe and for nine minutes...It’s just terrible, because this COVID virus affects minorities the worst, you know it affects minorities. The lowest on the totem pole is the one that’s catching the hell [being most affected by COVID-19], you know.

Similarly, Franklin, introduced above, drew a direct line between structural racism and the disproportional effects of COVID-19 on communities of color:

[People of color] are more affected because they don't have the essentials. […] People don't have no space and plus, most people, most poor people, not all poor people, have underlying issues like that, disease and all other things underlying. And me included. So, we have that on top of that. And most of the low-income jobs are in service jobs, like people who work on the train and the bus drivers. [...] COVID has exposed our society from top to bottom. And COVID, whether you are rich, poor, COVID shows what is really wrong with this country and what is really wrong with this society.

Although some participants believed that all racial or ethnic groups were equally at risk for COVID-19, most made direct connections between racial and/or structural inequalities and increased COVID-19 vulnerability for AABL populations. This was partly the result of recognizing their own economically disadvantaged status, as noted by Franklin.

Basic Needs

Participants were asked if COVID-19 had created challenges related to meeting basic needs. Some stated that COVID-19 had not impacted food availability and reported having consistent access to enough food both before and during the pandemic. Others, however, were already experiencing food insecurity before COVID-19 and had been “off and on struggling” for some time. Restricted travel due to COVID-19 caused or increased food insecurity for some and in some instances, a reduction in food quality. Those who discussed COVID-19 impeding regular access to groceries described poor access to fresh foods locally even before the pandemic, and that they had to travel outside their neighborhoods for high-quality fresh foods. Then, the pandemic restricted travel to their preferred food sources. Franklin, introduced above, described the following situation:

Yeah, because like I said, I cannot go as far as I would like to go in the Jewish neighborhood....I go to the [Jewish] neighborhoods to get fresh fruit, because I know like some things, they're going to have, they get fresh fruit. And […] the Black neighborhood, they get like all this hand-me-down fruit that the Jewish people don’t want. […] They [Jewish supermarkets] get foods and they keep it for two weeks, and after two weeks they don't want it, so they – instead of throwing it in the garbage, they send it to the poor neighborhoods to use it.

However, participants mobilized against food insecurity caused by COVID-19 by connecting to various local food sources and other support systems, including federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits, food pantries, and meals provided by the city social services administration, the department of education, and private non-profit organizations. Harold, for instance, was a 46-year-old Black man who had been living with HIV for 23 years who reported the following:

I’ve been very fortunate that the Grab ‘n Go [free bagged meals provided by the city school system], I make my rounds to various [places], I go from Lincoln Center to 114th [Street], I go to five different schools and grab them. I think the other day, though, I had so much food that I left it on the table in the lobby [of my building] for others to take, because I had so much. […] There was this pantry on 86th Street and I kept what I wanted and just left the rest, so – but the food situation, I'm fine. I wasn’t much of a cooker anyway, so me and a microwave – we go way back.

Thus, Harold adapted quickly to a constrained or disrupted food supply caused by COVID-19 travel restrictions and made use of publicly available resources. For those participants who were employed, COVID-19 typically affected their incomes in the form of a reduction in hours worked or job loss. As Olivia, a 45-year-old Black woman who had been living with HIV for 21 years, noted, access to the unemployment insurance benefit was also difficult and slow:

I did apply for it [unemployment insurance] back in March. I’m still waiting [...] Every time I call there the line is busy or their system is down or something. I don’t know. Just been surviving on a little bit of savings and I also get food stamps and cash assistance from HASA [the city government HIV/AIDS Services Administration]. But besides those and being able to maybe collect [from a] food pantry, so I’ve been OK. I’ve been OK.

Thus, participants commonly reported that the COVID-19 pandemic made it significantly more challenging to pay bills on time. Participants also reported difficulties that resulted from being forced to prioritize essential needs such as groceries over services that were important, but not essential, such as internet services. Michael, a 31-year-old Black man who was diagnosed with HIV seven years prior, had been trying to make ends meet by earning extra income covering for coworkers’ shifts since the outbreak of COVID-19:

I’m not bringing in as much income as I was before. So last month I had to put the cable bill, the internet bill to the side and I will pay it this week. But I had to put it to the side because I didn’t have the income. But those couple extra hours a week helped.

On the other hand, participants’ needs for internet access increased during the pandemic. Since most service settings stopped in-person contacts, vital health care services shifted to a telehealth format using phones, mobile applications (“apps”), or video conferencing programs. Yet, as noted above, most participants had at least basic phone service but were unable to use apps or video-conferencing. However, overall, while COVID-19 had a moderate impact on participants’ resources in the form of reduced access to fresh foods, decreased income, and interruptions in internet service, most of their basic needs were met. This was largely due to participants’ strategic mobilization of previously honed skills, in other words, “their hustle,” as Michael, introduced above, referred to it. Yet, as Michael went on to note, in contrast to higher-income individuals with more resources who can “stock up on those things,” the need to identify and access resources to meet basic needs “will force them [people with limited means] to be in more public places, interact with a lot more people, just because they have to get the necessary stuff that they need for their hustle,” thus placing them at risk for contracting COVID-19.

Stress and Coping with Fears and Concerns

As was noted above, for many participants the dearth of reliable information related to COVID-19, particularly during the early days and weeks of the pandemic, combined with conflicting advice from the news media and government officials, resulted in an increased sense of anxiety and insecurity. Participants reported feeling confused, anxious, and “paranoid,” and noted heightened concerns about their risk for contracting COVID-19 related to comorbidities common in this sample and among their loved ones such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, and cancer, in addition to HIV. Participants also expressed anxiety related to their inability to avoid densely populated areas. They described the added burdens of caring for and sometimes even losing individuals close to them to COVID-19. Edward, a 41-year-old Black man who had been living with HIV for 22 years, noted the following:

[COVID-19 is] a killer disease that will catch you regardless of where you're at and who you're with. Everybody around my way has a mask. But then I heard masks is no good. Come on, what are we supposed to do? What are we supposed to do? Like I said, I feel helpless. I feel helpless. [...] Because, oh, you can have it [COVID-19] and be walking around with it and not know it. So, they just made the disease so deadly, it's like some horror movie disease.

Edward went on to say:

To be Black, to have the [HIV] virus […] I mean come on, come on. I mean what else, you will give me the COVID too? They give me the COVID too? That would just be the trifecta. That would definitely be the cherry on top. Sprinkle on little COVID. [Like I don’t] have enough. There's not enough [to deal with].

Some participants noted that their concerns about contracting COVID-19 were so great that they voluntarily admitted themselves into the hospital for health conditions they mistook as COVID-19. Cedrick was a 53-year-old Latino man living with HIV for 27 years who, before being interviewed, had presented to an Emergency Department for what would eventually be diagnosed as “a touch of pneumonia” not related to COVID-19. He described:

Oh, because I couldn’t really breathe. I couldn’t taste my food and stuff like that, and it just really started bothering me because I’ve never been sick in my life. Even with [HIV], I’ve never been sick and that bothered me tremendously. And I didn’t know what was going on. […] But I was really scared. Trust me, I was calling [on] God and everybody. […] They didn’t find no corona in me, thank God. […] I thought I was going, I thought I was getting ready to pass over. I was getting ready to pass on over, yeah.

Despite an increased sense of anxiety and insecurity, it was common for participants to actively create strategies for coping with their fears and concerns and for keeping themselves safe. These fell into two broad, yet closely related categories; namely, COVID-19 prevention behaviors and second, methods for coping with COVID-19-related mental and emotional hardships.

As previously mentioned, participants were well aware of recommended methods for preventing the spread of the new coronavirus, and overall, they consistently practiced COVID-19 prevention behaviors, even if COVID-19 information sources weren’t completely trusted. Public transportation, especially the subway, was a major source of COVID-19 risk concern and participants tried to avoid it as much as possible. Michael, introduced above, highlighted how COVID-19 had affected his mobility:

Yeah, I normally try to stay home throughout the week. If I do go out, I’ll go and see my dad just to make sure he’s OK, like I [did]. And then I’ll come back home. I try not to take public transportation as far as I can. […] Yeah, I don’t take the train [laughter]. I haven’t taken the train since this has happened. And other than that, I just stay home.

Participants described strategies for coping with the mental and emotional hardships of both recommended and mandated COVID-19 restrictions, primary among them the need to stay home and avoid in-person social contact. Several participants spoke about creating everyday routines and strategies to manage COVID-19 related anxieties. For example, they described the different ways they tried to keep themselves distracted. These included hobbies, exercise and other ways of staying physically active, and calming and entertaining activities that could be done indoors, including prayer and meditation. As Sara, a 35-year-old Black woman who had been living with HIV for 14 years, noted:

I read. I sit here and sometimes I meditate and just have a lot of quiet time. I just allow myself to get my mind together, try not to put too much thought to my head, just try to be as free as I can be. So, I try to keep myself busy in the house. Whatever I can do, you know, whatever I can do. Talk to the kids, play with the kids, play some cards, you know, stuff like that.

Interactions with family, friends, and support networks, where possible, were also important ways of easing COVID-19-related anxieties. However, participants limited in-person interaction with others, including friends and loved ones, and the emotional hardship of not seeing loved ones was palpable. Raul, a 56-year-old Latino man living with HIV for 35 years, described his situation as follows:

I try not to go out unless, you know, I really have to. I don’t associate with friends anymore. I even put a sign on my door. I’m sorry, dangerous times, you know? Do not knock on the door [laughter]. My lungs already are really bad now and now my kidneys [too]. So, if I get sick I’m going to have a big problem. So, I’m really afraid not only because of me, and now you know also with my family. [...] And as soon as this started, I stopped visiting my mother. I go see her, but I don’t visit, and I don’t go in the house. All this year it’s been horrible. I miss her, you know? I miss looking at her.

Participants also described that engagement with family and friends increased compared to the time before COVID-19, but mainly via telephone, smartphone, and social media. Michael, introduced above, described being more engaged with friends since working from home:

I’m more connected. I speak to my friends almost every single day. We normally video chat throughout the day. I definitely have spoken to them a lot more in the last couple of weeks. [...] Because normally I work so I really don’t have that much time throughout the day to just be chatting and talking. But now that I’m home and I am working from home, [I] just pick up a phone call and just talk and check in on them. My communication with them has definitely increased.

Some maintained regular in-person contact with loved ones in addition to remote communication with members of their support network. Participants also created substitutes for social interaction that could provide some form of contact with people while keeping them safe. For example, one participant noted: “My socialization is going shopping, window shopping, for fruits and go up in the Bronx. […] I love to see people shopping, moving up and down […] wherever they're going.”

Finally, while some participants talked about shifts in substance use patterns in response to the pandemic, most reported no major substance use problems or changes in substance use. Yet, for some, using substances, albeit not necessarily at a level that was heavy or hazardous, was a way of dealing with loneliness and boredom due to COVID-19 restrictions. Gerald, a 32-year-old Latino man living with HIV for 16 years, noted:

OK I smoke marijuana. I’m smoking some right now. I mean I have to. Well, it helped me because it helps when I get bored. [...] I’ve been bored but the boredom leads to the creativity because as soon as I get bored, I turn around and I look at my art. […] Yeah, the boredom will creep in, but you got to fight it with creativity. You need the weed first then comes the art and then comes the creativity. […] Yeah, but if I don’t have weed then I don’t have the art, and that’s the problem. Because then I’m not inspired.

Thus, participants described feeling afraid, anxious, and worried about contracting COVID-19. In addition, the new coronavirus affected the availability of important resources and changed daily routines and connections with friends and loved ones. Participants drew from established skills to reduce exposure to COVID-19 and to meet basic needs. They also actively sought out ways to manage the emotional difficulties of COVID-19 restrictions and stay connected to their support systems.

Changes in Individual Health Behaviors

The pandemic also changed some participants’ health management behaviors, particularly regarding ART access, ART adherence, and telehealth for health care appointments. For some participants who were already regularly taking HIV medication before the outbreak of COVID-19, the pandemic had very little to no effect on ART adherence. For others, however, the increased risks associated with COVID-19 for PLWH catalyzed their re-initiation of ART or prompted them to increase their level of adherence to ART. They frequently described the primary reasons for doing so as anxiety related to increased susceptibility to COVID-19 due to HIV and other health issues. A second major factor was the increased ability to maintain consistent routines due to sheltering in place, which supported good adherence habits for some. For example, Raul, introduced above, stopped “diverting” his HIV medication (that is, being asked by a pharmacy to sell the ART prescription for cash, a practice that is illegal but common in NYC). He then initiated and became highly adherent to ART in a short period of time. Participants commonly noted that pharmacies and health care settings adapted to the pandemic by delivering ART directly to the participant’s door. This convenience played a role in ART uptake or increased adherence for some. Jordan, introduced above, recalled the following:

I was taking it [ART] before, but I wasn’t consistently taking it. Now I'm actually consistently taking it because of how the coronavirus came out, the way it came out. [...] AIDS and HIV don’t have nothing on this coronavirus [...] When AIDS and stuff first came out, they had something they had to keep switching it [HIV medications] and doing research. For this [the new coronavirus] they don’t even have anything, so you doggone right I'm going to take this [HIV] medicine now for real. I felt more like that you could just instantly die [from COVID-19], but with AIDS or whatever at least you’ve got a little bit of time left, this [COVID-19], they’re saying you don’t. [...] So that made me take it [ART] more consistently.

Similarly, Olivia, introduced above, made a rapid transition from regularly missing ART doses to near-perfect ART adherence, which she attributed directly to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic:

Before maybe I would miss a time and take it later but since this corona thing, it’s like I’ve set my alarm two different times to remind me. So, I take it all the time every day on time. Every day. You know. Because my doctor mentioned to me that since it’s an antiviral, it’s helping prevent or protect the coronavirus. I don’t know. So that’s why it’s even, you know, be a 100 percent more important to taking the [HIV] medicine. [...] Sometimes I would get home late so I would take it whenever I get home but now, I’ve been home for four months straight and so I’ve really, really been different from the daytime and I think I’m gonna keep doing that even when things open up again.

The majority of participants noted that because of COVID-19 nearly all health-related visits that did not require physical contact (e.g., bloodwork, ultrasounds, etc.) were held remotely. As noted above, some participants had limited access to forms of telehealth, as they did not have smartphones (and could not download mobile applications), computers, video conferencing applications, or internet access. The lack of facility with new technologies such as video conferencing applications that were needed to engage in virtual appointments was an additional hurdle. Although some participants reported being slightly dissatisfied with the lack of in-person interaction (e.g., “because like sometimes you can't see their face.”), most recalled finding various forms of telehealth equal to, if not more preferable than, in-person visits for medical and mental health purposes. This was especially the case when taking into account the considerable distances many participants traveled to receive quality care. As Gerald, introduced above, noted:

But my mental clinic that I go to, I go to a separate place for mental health. They’ve been all over the phone anyway because they’ve been closed [several] months now. But they’ve been doing video conferencing calls and that’s been interesting and handy and made me feel safe and made everyone feel safe. And I didn’t have to go anywhere, so it worked very well with my schedule.

Participants had varying reactions to remote substance use treatment and support services such as AA and NA, particularly group sessions. Responses ranged from consistently attending online group meetings to not attending any groups because of the digital format. As one participant noted, “I think one misses that social connection that – it’s wonderful that Zoom is available for those who are in NA and AA and all those other 12 steps. But it’s lacking that social component.”

Thus, COVID-19 influenced participants’ approaches to individual health management. For some, fear of the new coronavirus led to increased ART adherence and other initiatives to maintain good health. The introduction of telehealth was a significant change in their health care routines. Most participants, however, adjusted to the use of this new technology and saw its benefits.

Integration of Qualitative and Quantitative Findings

Overall, quantitative and qualitative findings were consistent, and the qualitative findings added depth, context, and nuance to the quantitative results. Quantitative data had a more detailed description of testing patterns compared to the qualitative, which did not mention testing. Quantitative results suggested the importance of altruism (92% stated they felt that they were contributing to the greater good by preventing themselves or others from getting coronavirus). Although altruism was not a theme in the qualitative results, the coding of the open-ended questions on community effects highlighted participants’ frustration that community members were not taking the public health prevention recommendations seriously enough. Food insecurity was a sub-theme in the qualitative results, and quantitative findings indicated that only a modest proportion (15%) were unable to obtain the food they needed. Taken together, the mixed-methods approach yielded a comprehensive description of participants’ experiences and perspectives of the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Discussion

The present study explores how AABL PLWH from low-SES backgrounds adapted to the novel coronavirus in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, focusing on a geographical area hard-hit by COVID-19. We found participants were significantly affected by the pandemic in domains such as avoiding in-person social contact, having health care and social service appointments canceled, including AA and NA meetings, avoiding public transportation, reductions in work hours and income, and problems with phone and internet service. Participants were early adopters of COVID-19 prevention recommendations, which they followed strictly, for the most part. We add to the literature by exploring the effects of COVID-19 on this subpopulation of PLWH and resultant active coping and survival strategies that PLWH in the present study implemented to successfully manage the COVID-19 crisis. We found they draw on knowledge and experience gleaned from years living with HIV to evaluate the risk of contracting the new coronavirus, assess the likelihood of an effective treatment for COVID-19 in the near future (which they believe is unlikely), and generally adapt to and cope with the many consequences of COVID-19. Findings also suggest that because participants in the present study live at the lowest SES strata, where many experience chronic food insecurity [41] and challenges meeting basic needs, even in times of relative economic stability and prosperity, they are well aware of the importance of self-reliance and “hustle” in times of crisis, since they can not necessarily count on government and public health officials to meet their needs. Thus, while previous research has explored the coping strategies of PWLH related to stigma [42, 43], adaptive and maladaptive coping [44], and stress [45], the present study extends this past research to focus on coping among PLWH in times of acute crisis.

Although it was fairly common for participants to know someone who had been diagnosed with or who had died from complications of COVID-19, participants themselves had relatively low rates of diagnosis with COVID-19, a finding consistent with similar research with PLWH in another urban area, Chicago, IL [46]. Although this low rate of infection with COVID-19 among participants in the present study is perhaps largely a result of interviews being conducted during the early stages of the pandemic, it may also be attributed in part to participants’ heightened vigilance and uptake of prevention strategies to minimize the risk of infection, grounded in large measure in their expertise on pandemics and infectious diseases developed as long-term survivors of HIV. Further, it is possible that participants’ prior health care service involvement, including attending clinical appointments and utilizing ancillary healthcare services, had a protective effect.

Overall, participants experienced disruption to health care services, laboratory services, and pharmacies, and this caused distress and concern. But, on the whole, they, and the systems they were engaged in, quickly adapted to public health requirements such as stay-at-home orders and shifted to using telehealth by phone, mobile applications, and/or video conferencing programs for appointments. Thus, for the most part, HIV care and ART availability were not seriously disrupted in this setting. However, there were some disruptions to substance use treatment services. Of concern, one-third of participants report increases in substance use, in response to stress, boredom, and a lack of in-person social contact [47]. Most participants in the present study were taking ART at the time of the interview. Interestingly, some of those not on ART or who were taking ART with sub-optimal adherence at the time the COVID-19 pandemic began reported COVID-19 prompted them to re-initiate ART or improve levels of adherence. Current research suggests, however, it is unlikely that ART is protective against contracting COVID-19, but certain ART regimens may protect against the most serious health consequences of COVID-19 [48].

Although the active use of information sources by PWLH for self-care has been previously examined [49], this is the first study to explore how these information-gathering strategies are applied by AABL PLWH during the emergence of a new pandemic. Interviews with participants were conducted during a time of exponential growth in COVID-19 incident cases and deaths in the local area and nationally, as well as within the context of rapid changes in available information, prevention recommendations, and legally enforceable executive orders, and the proliferation of conflicting official recommendations, guidelines, and ordinance from local, state, and federal agencies. As part of the participants’ evaluation of this information, distrust of authorities, and particularly federal authorities, was common, as was skepticism regarding much of the information being provided. On the other hand, local sources were generally trusted. These assessments of trustworthiness and accuracy of information sources appear consistent with reports provided by news agencies that highlight that local sources of information were indeed, on the whole, more accurate and trustworthy than information from federal sources [50, 51]. Participants did not commonly describe receiving COVID-19 related information from health care providers. It is possible that contact with providers was limited during this period, and that providers were hesitant or unable to provide clear guidance, given that they were subject to the same changing set of COVID-19 prevention recommendations as members of the society at large.

As noted above, PLWH in the present study were early adopters of recommended COVID-19 prevention strategies and describe themselves as more careful and more adherent to these recommendations than their peers in the larger community. In fact, they commonly experienced a sense of satisfaction related to contributing to the greater good by engaging in behaviors to prevent themselves or others from contracting the new coronavirus. The high levels of adherence to recommended COVID-19 prevention strategies, and according to participants, at levels even higher than among their peers, suggest that participants engaged in a process of fact-finding, information gathering, and thoughtful evaluation to determine what protective actions made the most sense for them. This is consistent with past research that highlights that distrust of medical information, health care settings, and medications does not necessarily preclude uptake of prevention information, engagement with such settings, and use of medications [52, 53], although distrust certainly has been found to reduce HIV care engagement and ART adherence [21]. Yet study results suggest the effort required among AABL PLWH to evaluate information in the context of distrust is considerable and that distrust has the potential to interfere with what would normally be reliable sources of information. Certainly, the need to evaluate and question medical information through the lens of distrust and informed by knowledge of past maltreatment by the medical and research establishment is not a burden shared by White PLWH. Thus, study findings highlight how the management of COVID-19 is more challenging for low-SES AABL PLWH compared to their White peers in the higher SES strata not living with HIV, as a result of medical distrust, and other factors related to poverty and scarce resources as we describe throughout this study. Indeed, past research highlights that medical distrust persists among AABL PLWH in part because it is reinforced by health system issues and discriminatory events that continue to this day [54], including those described by participants that occurred as the present study was taking place.

Critical race consciousness among AABL PLWH has previously been explored, including the role of critical consciousness as a facilitator of HIV treatment [55] and improved HIV outcomes [56]. Our findings contribute to this emerging literature by illustrating the ways the participants understand and experience interconnected structural barriers to successfully prevent COVID-19 infection and navigate a pandemic that once again disproportionately affects people from AABL backgrounds. As described above, much of the present study was conducted concurrently with a local, national, and global surge in the racial justice movement, as well as a growing awareness of racial/ethnic disparities in COVID-19 incidence and mortality rates. That participants quickly identified and articulated a deep understanding of the effects of structural racism on their options for food, housing, transportation, health care, and the means to protect themselves against COVID-19 infection and COVID-19-related anxieties suggest that public health interventions might benefit from garnering this awareness to create programs that not only focus on individual changes in behavior but also support participants’ efforts to create changes in their communities. As Metzl and Hansen (2014) have suggested, this necessitates the development of structural competency, a nuanced understanding of the relationship between individual health behaviors and their larger structural context of communities that have historically felt the brunt of the impact of structurally racist housing and economic policies, as well as the effects of environmental racism [57].

HIV is considered a pandemic of the poor [58]. The present study highlights the critical role of the “safety net” for populations at the lowest end of the SES continuum [59]. Participants in the present study were generally reliant on federal and local benefits programs including cash assistance, SNAP, Medicaid health insurance, and housing assistance available to them as PLWH. Previous research has examined how the safety net has supported HIV care, retention, and viral suppression [60, 61], linkages to health care [62], and medical outcomes [63] for PLWH. Results from the present study suggest that safety net programs and entitlements were vital and lifesaving during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, our findings also suggest that financial and SNAP support benefit levels may be set so low that participants are ultimately left with virtually no buffer, even before times of crisis, which in turn, creates serious gaps and needs when crises arise. Thus, AABL PLWH found the need to rely on friends, relatives, neighbors, and volunteer-run emergency food pantries for survival. Yet, local and federal benefits programs, including housing assistance, remained consistent even as the most severe impacts of COVID-19-related closures were felt (e.g., in social service agencies). Given its essential function, future research is needed to explore how the safety net can be expanded to better meet needs in times of crisis and beyond.

As HIV service settings closed their doors to in-person contact and switched to telehealth, cell phone, smartphone, computer, and internet access became critical for AABL PLWH. Cell phone service appeared to be adequate in this cohort, and most had at least basic phones through the Federal Communications Commission Lifeline program. The Lifeline program, colloquially referred to as the “Obama phone” program, provides low-income consumers a discount on voice and broadband services; participants may select phone or broadband services but not both [64]. Participants reported that their Obama phones met their needs in some ways but not others. One positive change during COVID-19 reported by participants was that the Obama phone program allowed for unlimited calls and texts during this crisis period, which provided a vital link to health care and social contacts. But, phone equipment and internet access were not usually adequate to support telehealth using video communications programs, and access to computers was poor. For example, participants commonly accessed computers through the library, but libraries were closed during this phase of COVID-19. Moreover, participants commonly expressed the need for training to improve computer skills, as many did not know how to use video communications programs for telehealth. These gaps in services for PLWH can be addressed to improve preparedness for future crises. For example, the Obama phone program can be enhanced to provide higher quality equipment, both phone and broadband services, and PLWH can be provided with computer access and training opportunities, including on how to use telehealth.

Limitations