Abstract

Previous research indicates a high burden of depression among adults living with HIV and an association between depression and poor HIV clinical outcomes. National estimates of diagnosed depression, depression treatment status, and association with HIV clinical outcomes are lacking. We used 2009–2014 data from the Medical Monitoring Project to estimate diagnosed depression, antidepressant treatment status, and associations with sustained viral suppression (all viral loads in past year < 200 copies/mL). Data were obtained through interview and medical record abstraction and were weighted to account for unequal selection probabilities and non-response. Of adults receiving HIV medical care in the U.S. and prescribed ART, 27% (95% confidence interval [CI] 25–29%) had diagnosed depression during the surveillance period; the majority (65%) were prescribed antidepressants. The percentage with sustained viral suppression was highest among those without depression (72%, CI 71–73%) and lowest among those with untreated depression (66%, CI 64–69%). Compared to those without depression, those with a depression diagnosis were less likely to achieve sustained viral suppression (aPR 0.95, CI 0.93–0.97); this association held for persons with treated depression compared to no depression (aPR 0.96, CI 0.94–0.99) and untreated depression compared to no depression (aPR 0.92, CI 0.89–0.96). The burden of depression among adults living with HIV in care is high. While in our study depression was only minimally associated with a lower prevalence of sustained viral suppression, diagnosing and treating depression in persons living with HIV remains crucial in order to improve mental health and avoid other poor health outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Globally, nearly 37 million people were living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) at the end of 2017 [1], and HIV infection was the fourth leading infectious cause of disability adjusted life-years (DALYs) [2]. With increasing availability of affordable antiretroviral therapy (ART) since the early 2000s, considerable progress has been made in the diagnosis and treatment of persons living with HIV/AIDS (PLWH). In 2017 21.7 million PLWH were accessing ART worldwide [3]. ART has considerably reduced morbidity and mortality due to HIV/AIDS [4, 5] and in high-income countries, PLWH with early access to ART have achieved near-normal life expectancy [6]. With these advances, the approach to HIV care in many settings has shifted from a primary focus on the infectious complications of immunodeficiency to chronic disease management and the prevention of illness, death and transmission among individuals taking ART [4, 7]. One important component of chronic disease management for PLWH is the diagnosis and treatment of depression.

Depression has a significant impact on PLWH. One in four persons living with HIV has symptoms of depression [8]. The relationship between HIV and depression is complex. Depression is both a risk factor for HIV transmission [9], and a consequence of HIV infection [10]. The onset of depression in PLWH is multifactorial and includes neurobiological changes, HIV-related stigma, life stressors, substance use and functional health status [11, 12]. Once present, depression significantly affects health and wellbeing and is associated with poor behavioral and psychosocial outcomes such as social isolation, decreased work performance, anxiety, substance use disorder, and suicide [13,14,15], as well as with poor outcomes for medical comorbidities such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease and cancer [16,17,18,19].

In addition to poor psychosocial and general health outcomes, depression has also been linked with poor HIV-related health outcomes. Previous studies have suggested that persons dually diagnosed with HIV and depression are less likely to adhere to ART regimens and more likely to have detectable HIV viral loads than those without depression [20, 21], and have shown antidepressant pharmacotherapy to increase the probability of ART adherence [22] and HIV viral suppression [23]. Many of these studies, however, were conducted more than 10 years ago and with relatively small sample sizes. There are no national estimates on the association of antidepressant pharmacotherapy with HIV clinical outcomes. In this study we assessed the prevalence of diagnosed depression and accompanying pharmacotherapy treatment status in individuals in HIV clinical care in the United States who were prescribed ART to explore whether treated and untreated depression are differently associated with sustained HIV viral suppression.

Methods

Medical Monitoring Project design, Sampling, and Data Collection

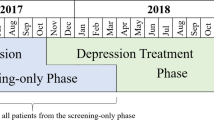

The Medical Monitoring Project (MMP) is an HIV surveillance system designed to produce nationally representative estimates of behavioral and clinical characteristics of adults living with HIV in the United States. MMP is a complex-sample, annual cross-sectional survey. For the 2009–2014 data collection cycles, MMP described adults receiving HIV clinical care. US states and territories were sampled first, followed by facilities providing HIV care within sampled jurisdictions, and then by adults living with HIV (persons aged 18 years and older) who had at least one medical care visit during January–April of each cycle at participating facilities. Data were collected through face-to-face or telephone interviews and medical record abstractions. Medical records were abstracted for the 1 year preceding interview date for the 2009–2012 cycles and for the 2 years preceding interview date for the 2013 and 2014 cycles (hereafter referred to as the “surveillance period”). All sampled states and territories participated in MMP: California (including the separately funded jurisdictions of Los Angeles County and San Francisco), Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Illinois (including Chicago), Indiana, Michigan, Mississippi, New Jersey, New York (including New York City), North Carolina, Oregon, Pennsylvania (including Philadelphia), Puerto Rico, Texas (including Houston), Virginia, and Washington. During the six MMP cycles included in analyses, the eligibility-adjusted facility response rate ranged from 76–86% and eligibility-adjusted individual patient response rate ranged from 49–56% [24,25,26,27,28]. Per MMP procedure, data were weighted on the basis of known probabilities of selection at state or territory, facility, and patient levels, as well as to adjust for nonresponse by using predictors of patient-level response, including facility size, race/ethnicity, time since HIV diagnosis, and age group, to produce nationally representative estimates.

Ethics Statement

MMP, as a public health surveillance activity, was determined to be non-research in accordance with the federal human subjects protection regulations at 45 Code of Federal Regulations 46.101c and 46.102d and CDC’s Guidelines for Defining Public Health Research and Public Health Non-Research [29]. Participating states or territories and facilities obtained local Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval to conduct MMP, if required locally.

Variables Used in the Analysis

“Any depression” was defined as documentation of depression on either outpatient or inpatient medical record abstraction from the patient’s main source of outpatient HIV clinical care. Those diagnosed with depression were further categorized as having either “treated depression” or “untreated depression” based on the presence or absence of a prescription for an antidepressant in outpatient or inpatient medical records. Non-pharmacotherapy depression treatment modalities such as psychotherapy were not captured. Sustained viral suppression was defined as all HIV RNA levels undetectable or less than 200 copies per milliliter during the 12 months preceding interview date.

Analytic Methods

We estimated weighted percentages and associated 95% confidence intervals (CI) for having any depression, treated depression and untreated depression. We then restricted our study population to those prescribed ART and used the Rao–Scott Chi square test, a design-adjusted version of the Pearson Chi square test used for survey data analysis, to test associations of behavioral and clinical characteristics with any depression and untreated depression. We estimated weighted percentages for sustained viral suppression stratified by depression status and used multivariable logistic regression and adjusted marginal predictions to estimate adjusted prevalence ratios (aPR) of sustained HIV viral suppression conditional on depression status. We constructed three models: (1) estimating the prevalence ratio of sustained viral suppression for those with any versus no depression, (2) estimating the prevalence ratio of sustained viral suppression for those with untreated depression or treated depression separately versus no depression, and (3) estimating the prevalence ratio of sustained viral suppression for those with treated versus untreated depression. Each model was adjusted for gender [30, 31], race [31, 32], homelessness [33, 34], health insurance status [35, 36], drug use [15, 37], and time since HIV diagnosis [38, 39]. In all multivariable analyses we included variables as potential confounders that were a priori and statistically determined to be significantly associated with any depression and sustained viral suppression (p ≤ 0.05). To assess potential bias introduced by the change in the surveillance period (12 vs. 24 months) between the 2012 and 2013 MMP cycles, we performed a sensitivity analysis, separately estimating the prevalence of depression and its association with sustained viral suppression using 2009–2012 and 2013–2014 data. All analyses were performed using procedures for survey data analysis in SAS/STAT 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and SUDAAN 11 (RTI International, Research Triangle Park, NC).

Results

Depression Prevalence

Overall, an estimated 27% (95% CI 25–29%) of U.S. adults receiving care for HIV infection during 2009 to 2014 had diagnosed depression during the surveillance period; 10% (CI 9–10%) had depression and were not prescribed antidepressants and 17% (CI 16–19%) had depression and were prescribed antidepressants. Ninety-two percent were prescribed ART and comprised our analytic sample for the remainder of analyses; among this sample 27% (CI 25%–27%) had diagnosed depression and 9% (CI 9%–10%) were not prescribed antidepressants (data not shown). In unadjusted analyses, depression diagnosis was associated with sex (p < 0.01), sexual orientation (p < 0.01), race/ethnicity (p < 0.01), and having insurance coverage (p < 0.01) (Table 1). Respondents whose household incomes were at or below the federal poverty level had a higher prevalence of depression compared with those living above the poverty level (p < 0.01), as did those who were homeless in the past 12 months compared with those who were not (p < 0.01), and those whose HIV infection was diagnosed at least 10 years ago compared with those who were diagnosed with HIV fewer than 10 years ago (p < 0.01). Similarly, untreated versus no depression was associated with sex (p < 0.01), sexual orientation, (p < 0.01), income at or below the poverty level (p < 0.01), recent homelessness (p < 0.01), having insurance coverage (p = 0.01), and a longer duration since HIV diagnosis (p = 0.04).

Depression and Sustained HIV Viral Suppression

In unadjusted analyses, the percentage of persons with sustained viral suppression was highest among those without depression (72%, CI 71–73%) and lowest among those with untreated depression (66%, CI 64–69%) (Table 2). When comparing those with a depression diagnosis to those without, after controlling for gender, race, homelessness, health insurance status, drug use, and time since HIV diagnosis, those with a diagnosis of depression were less likely to achieve sustained viral suppression (aPR 0.95, CI 0.93–0.97). When comparing those with either treated or untreated depression to those without depression, after adjusting for the same characteristics, those with treated and untreated depression were less likely to achieve sustained HIV viral suppression (aPRs 0.96 [0.94–0.99]; 0.92 [0.89–0.96], respectively). In adjusted multivariable analyses there was no difference in the prevalence of sustained viral suppression among those with treated compared to untreated depression (aPR 1.04 [1.00-1.08]) (data not shown). Sensitivity analyses (data not shown) demonstrated no significant impact of the change in surveillance period on the observed associations.

Discussion

Our study indicates that approximately one-quarter of adults living with HIV in care are also experiencing depression, and the majority have been prescribed antidepressants. In addition, among adults living with HIV in care and prescribed ART, depression and antidepressant treatment status were only minimally associated with differences in sustained viral suppression.

These are the first nationally representative estimates of diagnosed depression and antidepressant treatment status among adults living with HIV in care in the U.S. Previous national depression burden estimates have relied upon self-reported symptoms of depression, yet still indicate a depression prevalence similar to the 25% in this population [8]. This 25% is significantly higher than the burden of depression in the general population; Do and colleagues found a prevalence of current depression that was 3 times as high among adults in HIV care as within the general population of U.S. adults [8]. The reasons for this are likely multifactorial and include HIV-related stigma, life stressors, substance use and functional health status [11]. A national estimate of the burden of depression among US adults living with HIV in care, including antidepressant treatment status, is crucial in informing clinician efforts to screen and treat depression in their adult patients living with HIV.

Among PLWH, depression has previously been associated with decreased rates of ART prescription, decreased ART adherence, decreased CD4 counts, increased viral loads, and increased incidence of comorbid illness [20, 21, 40,41,42,43], and is in fact recognized in the 2014 recommendations for HIV prevention with adults and adolescents living with HIV as a factor that could decrease ART adherence [44]. Our study found that individuals dually diagnosed with HIV and depression and treated with ART are only minimally less likely to achieve sustained viral suppression. This is encouraging with regards to HIV clinical outcomes, suggesting that for many, depression may not be a substantial barrier to ART adherence, but somewhat contradicts previously published reports. This finding may reflect changes over time in HIV pharmacotherapy, including development of single-tablet ART regimens, decreased pill burden, and increased tolerability [45,46,47], with simpler ART regimens facilitating improved ART adherence in persons dually diagnosed with HIV and depression.

The psychosocial and physical tolls of depression are enormous. Individuals with depression are more likely to experience social isolation, decreased work performance, anxiety, and substance use disorder, and are more likely to attempt suicide [13,14,15]. They are also more likely to develop cardiovascular disease and diabetes, and have higher all-cause mortality than individuals without depression [19, 48,49,50,51]. Productive years lost due to disability from depression are greater than those from diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer [52]. The potential benefits of diagnosing and treating depression are similarly enormous. A 2016 WHO study modeling the benefits of scaling up depression and anxiety treatment among persons aged 15 years and older in 35 low-, middle- and high-income countries estimated a gain of 43 million extra years of healthy life over a 15 year period [53]. Among those living with HIV, studies evaluating the associations between depression and non-HIV related clinical outcomes are limited. However, we know the burden of many non-HIV related clinical outcomes to be high among PLWH [54,55,56], and the coexistence of depression can only magnify this problem. Further research to determine specific risk factors that increase the likelihood of a depression diagnosis could guide clinician screening efforts. In the meantime, it is crucial that providers remain diligent in diagnosing and treating depression among all of their patients living with HIV.

Guidelines addressing depression treatment for persons living with HIV exist, but could benefit from updates to reflect advances in HIV pharmacotherapy. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Persons with HIV/AIDS were published in 2000, and suggests that individuals living with HIV infection should be treated for depression per standard depression treatment recommendations. While the organization has since published a 2006 Guideline Watch that includes some updated information about several aspects of HIV infection, including advances in ART [57], the Guideline has not been formally reviewed or updated since its initial publication [58]. Given the shifting landscape in HIV pharmacotherapy, updated guidelines to assist providers in selecting appropriate antidepressant regimens that will not disrupt HIV treatment plans could be of great assistance.

Limitations

This study has limitations. We relied on provider diagnosis of depression to assess depression status; patients with depression not diagnosed by their provider would not have been categorized as depressed. Other analyses have examined self-reported depression symptoms [8]. Moreover, we abstracted medical records only from individuals’ primary HIV provider; records held at other locations were not included in the analysis. It is possible that depression diagnoses were missed in this way. We were not able to assess the prevalence of non-pharmacotherapy treatment modalities. It is possible that some of the 35% of individuals not prescribed pharmacotherapy in our study were exclusively receiving non-pharmacotherapy treatment modalities such as psychotherapy. We did not assess predictors of any versus no depression and treated versus untreated depression. Future analyses of these factors could have important clinical implications for targeted depression screening and treatment. Finally, the study population consists of PLWH who are receiving HIV care, therefore our findings are not generalizable to PLWH who are not receiving HIV care.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while one-quarter of HIV-positive adults in care in the United States have diagnosed depression, depression is associated with only a slightly lower prevalence of sustained viral suppression. However, it is important to note that depression, when undiagnosed and untreated, can result in poor psychosocial and physical health outcomes regardless of HIV status. Given the high prevalence of depression among persons living with HIV, it is crucial that HIV clinical providers remain vigilant in diagnosing and treating depression in their patients.

References

World Health Organization. Global Health Observatory data. https://www.who.int/gho/hiv/en/. Accessed 12 July 2019.

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. GBD Compare. 2017. https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/. Accessed 12 July 2019.

UNAIDS. Fact Sheet. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet. Accessed 12 July 2019.

Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):493–505.

Lundgren JD, Babiker AG, Gordin F, Emery S, Grund B, Sharma S, et al. Initiation of antiretroviral therapy in early asymptomatic HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(9):795–807.

May MT, Gompels M, Delpech V, Porter K, Orkin C, Kegg S, et al. Impact on life expectancy of HIV-1 positive individuals of CD4+ cell count and viral load response to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS (London, England). 2014;28(8):1193–202.

Montaner JS, Lima VD, Barrios R, Yip B, Wood E, Kerr T, et al. Association of highly active antiretroviral therapy coverage, population viral load, and yearly new HIV diagnoses in British Columbia, Canada: a population-based study. Lancet. 2010;376(9740):532–9.

Do AN, Rosenberg ES, Sullivan PS, Beer L, Strine TW, Schulden JD, et al. Excess burden of depression among HIV-infected persons receiving medical care in the united states: data from the medical monitoring project and the behavioral risk factor surveillance system. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3):e92842.

Gowda C, Coppock D, Brickman C, Shaw PA, Gross R. Determinants of HIV transmission risk among HIV-infected persons engaged in care. AIDS Educ Prev. 2016;28(5):440–52.

Simoni JM, Safren SA, Manhart LE, Lyda K, Grossman CI, Rao D, et al. Challenges in addressing depression in HIV research: assessment, cultural context, and methods. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(2):376–88.

Glynn TR, Llabre MM, Lee JS, Bedoya CA, Pinkston MM, O’Cleirigh C, et al. Pathways to health: an examination of hiv-related stigma, life stressors, depression, and substance use. Int J Behav Med. 2019;26:286.

Schuster R, Bornovalova M, Hunt E. The influence of depression on the progression of HIV: direct and indirect effects. Behav Modif. 2012;36(2):123–45.

Bozorgmehr A, Alizadeh F, Ofogh SN, Hamzekalayi MRA, Herati S, Moradkhani A, et al. What do the genetic association data say about the high risk of suicide in people with depression? A novel network-based approach to find common molecular basis for depression and suicidal behavior and related therapeutic targets. J Affect Disord. 2018;229:463–8.

Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD, Burnam MA, Rogers W, Daniels M, et al. The functioning and well-being of depressed patients. Results from the medical outcomes study. Jama. 1989;262(7):914–9.

Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Compton W, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(8):807–16.

Hunter JC, DeVellis BM, Jordan JM, Sue Kirkman M, Linnan LA, Rini C, et al. The association of depression and diabetes across methods, measures, and study contexts. Clin Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;4:1.

Lichtman JH, Froelicher ES, Blumenthal JA, Carney RM, Doering LV, Frasure-Smith N, et al. Depression as a risk factor for poor prognosis among patients with acute coronary syndrome: systematic review and recommendations: a scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation. 2014;129(12):1350–69.

Thombs BD, de Jonge P, Coyne JC, Whooley MA, Frasure-Smith N, Mitchell AJ, et al. Depression screening and patient outcomes in cardiovascular care: a systematic review. JAMA. 2008;300(18):2161–71.

Drudi LM, Ades M, Turkdogan S, Huynh C, Lauck S, Webb JG, et al. Association of depression with mortality in older adults undergoing transcatheter or surgical aortic valve replacement. JAMA Cardiology. 2018;3:191.

Carrico AW, Bangsberg DR, Weiser SD, Chartier M, Dilworth SE, Riley ED. Psychiatric correlates of HAART utilization and viral load among HIV-positive impoverished persons. AIDS (London, England). 2011;25(8):1113–8.

Springer SA, Dushaj A, Azar MM. The impact of DSM-IV mental disorders on adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy among adult persons living with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(8):2119–43.

Horberg MA, Silverberg MJ, Hurley LB, Towner WJ, Klein DB, Bersoff-Matcha S, et al. Effects of depression and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use on adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy and on clinical outcomes in HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (1999). 2008;47(3):384–90.

Mills JC, Harman JS, Cook RL, Marlow NM, Harle CA, Duncan RP, et al. Comparative effectiveness of dual versus single-action antidepressants on HIV clinical outcomes in HIV-infected people with depression. AIDS (London, England). 2017;31(18):2515–24.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral and clinical characteristics of persons receiving medical care for HIV infection—Medical Monitoring Project, United States, 2012. 2015. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-HSSR_MMP_2012.pdf. Accessed 13 Oct 2017.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral and clinical characteristics of persons receiving medical care for HIV infection—Medical Monitoring Project, United States, 2014 Cycle (June 2014–May 2015). 2016. Contract No.: 17.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral and clinical characteristics of persons receiving medical care for HIV infection—Medical Monitoring Project, United States, 2013 Cycle (June 2013–May 2014). 2016. Contract No.: 16.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral and clinical characteristics of persons receiving medical care for HIV infection—Medical Monitoring Project, United States, 2011. 2015. Contract No.: 10.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral and clinical characteristics of persons receiving medical care for HIV infection—Medical Monitoring Project, United States, 2010. 2014. Contract No.: 9.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Distinguishing public health research and public health nonresearch: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2010. http://www.cdc.gov/od/science/integrity/docs/cdc-policy-distinguishing-public-health-research-nonresearch.pdf. Accessed 22 June 2015.

Salk RH, Hyde JS, Abramson LY. Gender differences in depression in representative national samples: meta-analyses of diagnoses and symptoms. Psychol Bull. 2017;143(8):783–822.

Beer L, Mattson CL, Bradley H, Skarbinski J. Understanding cross-sectional racial, ethnic, and gender disparities in antiretroviral use and viral suppression among HIV patients in the United States. Medicine. 2016;95(13):e3171.

Hooker K, Phibbs S, Irvin VL, Mendez-Luck CA, Doan LN, Li T, et al. Depression among older adults in the united states by disaggregated race and ethnicity. Gerontologist. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gny159.

Brown MA, Gellatley W, Hoffman A, Dowdell L, Camac A, Francois R, et al. Medical complications of homelessness: a neglected side of men’s health. Int Med J. 2019;49(4):455–60.

Thakarar K, Morgan JR, Gaeta JM, Hohl C, Drainoni ML. Homelessness, HIV, and incomplete viral suppression. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2016;27(1):145–56.

Park H, Song I, Shin JY. High Prevalence of depression diagnosis among medical aid beneficiaries: a Korean health insurance database study. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2017;29(8):692–7.

Ludema C, Cole SR, Eron JJ, Edmonds A, Holmes GM, Anastos K, et al. Impact of health insurance, ADAP, and income on HIV Viral suppression among US women in the women’s interagency HIV study, 2006–2009. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (1999). 2016;73(3):307–12.

Tolson C, Richey LE, Zhao Y, Korte JE, Brady K, Haynes L, et al. Association of substance use with hospitalization and virologic suppression in a Southern academic HIV clinic. Am J Med Sci. 2018;355(6):553–8.

Sowa NA, Bengtson A, Gaynes BN, Pence BW. Predictors of depression recovery in HIV-infected individuals managed through measurement-based care in infectious disease clinics. J Affect Disord. 2016;192:153–61.

Chhim K, Mburu G, Tuot S, Sopha R, Khol V, Chhoun P, et al. Factors associated with viral non-suppression among adolescents living with HIV in Cambodia: a cross-sectional study. AIDS Res Ther. 2018;15(1):20.

Nanni MG, Caruso R, Mitchell AJ, Meggiolaro E, Grassi L. Depression in HIV infected patients: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(1):530.

Mayston R, Kinyanda E, Chishinga N, Prince M, Patel V. Mental disorder and the outcome of HIV/AIDS in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review. AIDS (London, England). 2012;26(Suppl 2):S117–35.

Mitchell AJ, Lord O, Malone D. Differences in the prescribing of medication for physical disorders in individuals with v. without mental illness: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;201(6):435–43.

Gonzalez JS, Batchelder AW, Psaros C, Safren SA. Depression and HIV/AIDS treatment nonadherence: a review and meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (1999). 2011;58(2):181–7.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Health Resources and Services Administration, National Institutes of Health, American Academy of HIV Medicine, Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, International Association of Providers of AIDS Care, et al. Recommendations for HIV prevention with adults and adolescents with HIV in the United States. 2014.

Yager J, Faragon J, McGuey L, Hoye-Simek A, Hecox Z, Sullivan S, et al. Relationship between single tablet antiretroviral regimen and adherence to antiretroviral and non-antiretroviral medications among Veterans’ affairs patients with human immunodeficiency virus. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2017;31(9):370–6.

Truong WR, Schafer JJ, Short WR. Once-daily, single-tablet regimens for the treatment of HIV-1 infection. Pharm Therapeutics. 2015;40(1):44–55.

Beer L, Mattson CL, Bradley H, Shouse RL. Trends in ART prescription and viral suppression among HIV-positive young adults in care in the United States, 2009–2013. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (1999). 2017;76(1):e1–6.

Nicholson A, Kuper H, Hemingway H. Depression as an aetiologic and prognostic factor in coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis of 6362 events among 146 538 participants in 54 observational studies. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(23):2763–74.

Barefoot JC, Helms MJ, Mark DB, Blumenthal JA, Califf RM, Haney TL, et al. Depression and long-term mortality risk in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1996;78(6):613–7.

Pan A, Lucas M, Sun Q, van Dam RM, Franco OH, Manson JE, et al. Bidirectional association between depression and type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(21):1884–91.

Moise N, Khodneva Y, Jannat-Khah DP, Richman J, Davidson KW, Kronish IM, et al. Observational study of the differential impact of time-varying depressive symptoms on all-cause and cause-specific mortality by health status in community-dwelling adults: the REGARDS study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(1):e017385.

Feigin V. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1545–602.

Chisholm D, Sweeny K, Sheehan P, Rasmussen B, Smit F, Cuijpers P, et al. Scaling-up treatment of depression and anxiety: a global return on investment analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(5):415–24.

Mayer KH, Loo S, Crawford PM, Crane HM, Leo M, DenOuden P, et al. Excess clinical comorbidity among HIV-infected patients accessing primary care in US community health centers. Public Health Rep. 2018;133(1):109–18.

Drozd DR, Kitahata MM, Althoff KN, Zhang J, Gange SJ, Napravnik S, et al. Increased risk of myocardial infarction in HIV-infected individuals in North America compared with the general population. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. (1999). 2017;75(5):568–76.

Sackoff JE, Hanna DB, Pfeiffer MR, Torian LV. Causes of death among persons with AIDS in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: New York city. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(6):397–406.

American Psychiatric Association. Guideline Watch: Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with HIV/AIDS. 2006. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/hivaids-watch.pdf. Accessed 30 Mar 2018.

American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with HIV/AIDS. 2000.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participating Medical Monitoring Project (MMP) providers, facilities, project areas, and Provider and Community Advisory Board members. They also acknowledge the contributions of the Clinical Outcomes Team, the Behavioral and Clinical Surveillance Branch, and other members of the Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention at CDC and the MMP 2009–2014 Study Group Members: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/systems/mmp/resources.html#StudyGroupMembers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The following are contributions of authors to the study: RHG contributed to data analysis and wrote the article; JW contributed to data analysis and edited the article; PSS contributed to data analysis and edited the article; QL contributed to data analysis; FS contributed to data analysis; HB contributed to data analysis and edited the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gokhale, R.H., Weiser, J., Sullivan, P.S. et al. Depression Prevalence, Antidepressant Treatment Status, and Association with Sustained HIV Viral Suppression Among Adults Living with HIV in Care in the United States, 2009–2014. AIDS Behav 23, 3452–3459 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-019-02613-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-019-02613-6