Abstract

Life chaos, the perceived inability to plan for and anticipate the future, may be a barrier to the HIV care continuum for people living with HIV who experience incarceration. Between December 2012 and June 2015, we interviewed 356 adult cisgender men and transgender women living with HIV in Los Angeles County Jail. We assessed life chaos using the Confusion, Hubbub, and Order Scale (CHAOS) and conducted regression analyses to estimate the association between life chaos and care continuum. Forty-eight percent were diagnosed with HIV while incarcerated, 14% were engaged in care 12 months prior to incarceration, mean antiretroviral adherence was 65%, and 68% were virologically suppressed. Adjusting for sociodemographics, HIV-related stigma, and social support, higher life chaos was associated with greater likelihood of diagnosis while incarcerated, lower likelihood of engagement in care, and lower adherence. There was no statistically significant association between life chaos and virologic suppression. Identifying life chaos in criminal-justice involved populations and intervening on it may improve continuum outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The HIV epidemic disproportionately affects the incarcerated population in the US, with an estimated 1.3% prevalence among prisoners that is approximately three times that of the general population [1]. Furthermore, compared to people living with HIV (PLH) in the US general population, incarcerated PLH are often less likely to have met HIV care continuum milestones [2, 3] —engaged in care, received and adhered to antiretroviral therapy (ART) and achieved virologic suppression—at the time of incarceration [4,5,6,7]. This disproportionate burden as well as the profound challenges in achieving the care continuum reflect how the incarcerated population represents one of the most socially and economically marginalized groups in the US [8,9,10]. Understanding the lived experience of navigating social and structural barriers to care in community settings may help us to improve the HIV care continuum among incarcerated PLH and those returning from custody.

The idea that life chaos—perceived inability to plan for and anticipate the future—leads to adverse outcomes was first proposed by Matheny and colleagues in the field of child development [11]. Their tool, the Confusion, Hubbub, and Order Scale (CHAOS), has since been adapted to adults to measure various aspects of stability and predictability in daily life, ranging from a person’s perceived ability to organize a routine and keep a schedule, to their sense of certainty regarding their future housing or source of income [12]. While life chaos remains an underexplored concept in the health literature, a limited number of studies have demonstrated that it predicts important health outcomes. Life chaos predicted missed appointments and poor medication adherence among PLH [12, 13] and patients with chronic illness, [14, 15] as well as risky sexual behavior among men who have sex with men (MSM) [16]. In addition, life chaos was associated with structural barriers to HIV care—poverty, homelessness, and having unmet needs for financial, employment, and food support services—supporting its validity [12, 13].

The literature on criminal justice-involved PLH suggests high levels of chaos in their lives. They frequently experience poverty, comorbid substance use disorder [17, 18] housing instability [19], and social isolation from HIV-related stigma, all of which may contribute to life chaos [13, 16, 20]. Many come from communities where households and relationships are disrupted from high rates of incarceration [21]. Finally, social and economic marginalization due to overlapping stigmatized identities likely compound the life chaos. For example, incarcerated young black MSM often lose access to resources in their community due to homonegativity [22] and have higher rates of homelessness and lower rates of health insurance prior to incarceration compared to other incarcerated men [6]; transgender women experience discrimination in employment, healthcare and family settings and victimization while incarcerated [23, 24].

Guided by the ecosocial theory that posits the importance of examining health inequities in the context of individual, interpersonal, and structural factors [25], we highlight two interpersonal factors that are known to shape the HIV epidemic among incarcerated PLH: social support and HIV-related stigma. Supportive social relationships have been shown to be positively associated with protective HIV-related behaviors, fewer HIV infections, and better HIV care continuum outcomes in general [26,27,28,29,30], including for incarcerated PLH [18, 31, 32]. Social support provides material resources or emotional support to buffer the effects of stressors [33, 34], and can potentially counter the effects of life chaos [16]. On the other hand, social relationships may also be a source of HIV-related stigma, the devaluation and discrimination of PLH, which can be a potent barrier to continuum of care outcomes [35, 36]. For PLH with criminal-justice involvement, HIV-related stigma is associated with hiding one’s HIV serostatus, refusing to take ART, and relapsing into substance use [18, 31, 32, 37].

Using baseline data collected from a sample of PLH from the Los Angeles County Men’s Central Jail who participated in a randomized controlled trial of a peer navigation intervention after release from jail, we examined whether life chaos, social support, and HIV-related stigma prior to incarceration were associated with levels of HIV care continuum engagement upon jail entry. We hypothesized that life chaos was associated with each of the HIV care continuum steps.

Methods

Study Setting and Population

This study is based on the baseline data collected for the LINK LA study, a two-group, randomized trial of a peer navigation intervention for PLH released from jail, as previously published [38]. To summarize briefly, we recruited participants from Los Angeles County Men’s Central Jail. They were eligible for study participation if they were: (1) HIV seropositive; (2) age 18 or older (3) cisgender men or transgender women; (4) English- or bilingual Spanish-speaking; (5) planning to reside in LA County upon release; and (6) eligible for antiretroviral therapy or incarcerated on antiretroviral therapy [38]. Exclusion criteria were: (1) inability to give informed consent; (2) planned transfer to prison; and (3) stay in jail < 5 days. Of a total of 465 potentially eligible persons, we enrolled 356 in the study (105 were screened but not eligible, and four declined).

Data Collection

From December 2012 through June 2015, research staff conducted face-to-face baseline interviews approximately one week prior to release from jail. The team also obtained electronic medical record data on HIV viral load, which was routinely drawn several days after the participants diagnosed with or known to have HIV arrived at jail. Participants were compensated $25 for the interview.

Primary Variables of Interest

Primary dependent variables were achievement of steps in the HIV care continuum prior to the jail stay [39]: routine HIV testing in the community (vs. only while incarcerated), engagement in care, ART adherence, and viral suppression. To identify those who did not participate in routine HIV testing, we asked whether the participant first tested positive for HIV during the current or a previous incarceration in jail or prison: participants who first tested positive while incarcerated were deemed not to have achieved that milestone. To measure engagement in care, we asked whether participants who had been diagnosed more than 12 months prior to this incarceration had received at least one HIV primary care visit in the community 12 months prior to entering jail. We assessed ART adherence over the 30 days prior to incarceration using a scale of 0–100% rating scale, generally called a Visual Analog Scale [40,41,42]. Finally, we defined virologic suppression as viral load < 400 copies/ml on first viral load after jail entry. This cutoff was selected to account for viral blips that do not result in any clinically significant viral replication [5, 43, 44].

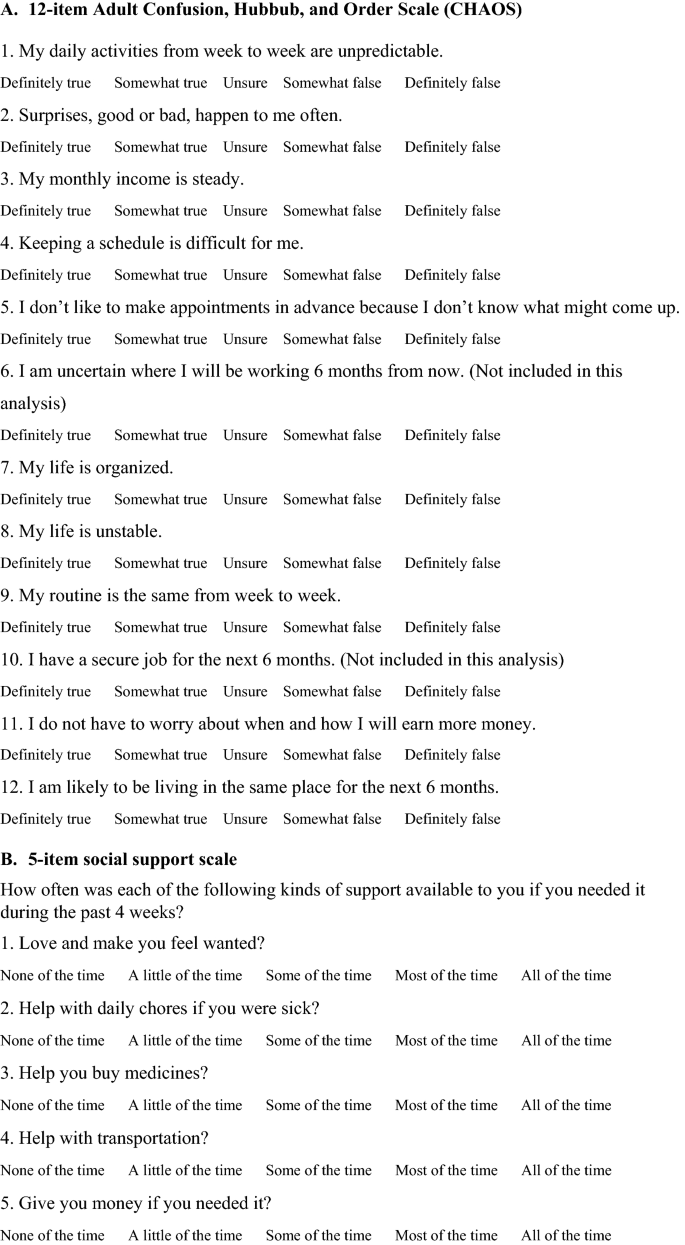

The primary independent variables included measures of life chaos, social support, and HIV-related stigma (see “Appendix”). To measure life chaos, we administered the 12-item Confusion, Hubbub, and Order Scale (CHAOS) adapted for adults, which measures predictability of life circumstances, ability to plan and anticipate the future, and reliability of income, employment, housing [12]. In this analysis, we excluded two items about certainty of employment in six months in the future, given that the participants were incarcerated and unemployed at the time of interview. Each item was scored on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from “definitely true” to “definitely false.” The items were averaged for the total score (from 1 to 5), with higher numbers representing more chaos. The final 10-item chaos scale showed acceptable internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.76).

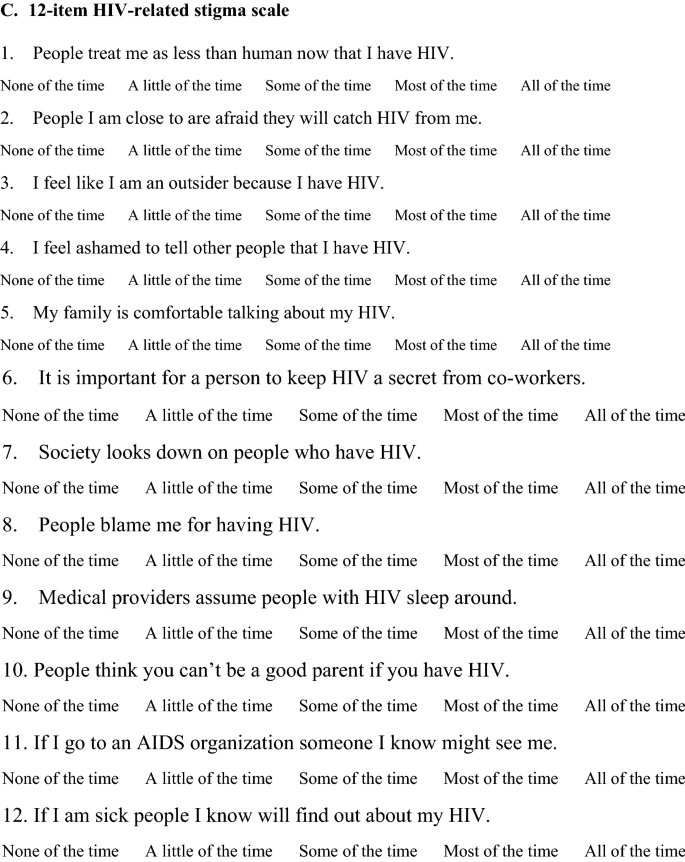

We measured social support using a 5-item scale that was derived from a previous tool designed to measure perceived availability of emotional and practical support [45,46,47]. Each item was scored on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from “none of the time” to “all of the time.” The scale showed excellent internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.90). The items were averaged to create a scale score (from 1 to 5), with higher values representing greater social support.

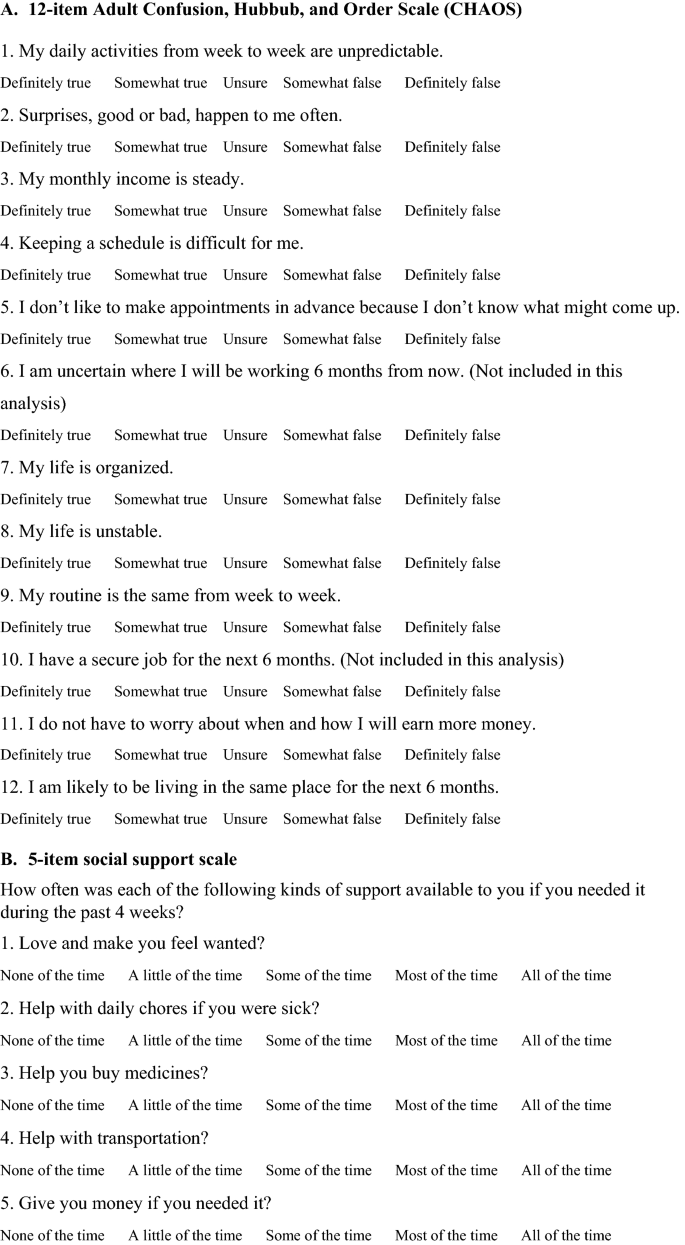

We measured HIV-related stigma using a 12-item version of an established measure that taps four dimensions of stigma: negative stereotypes associated with HIV, disclosure concerns, treatment by others, and internalization of shame [48, 49]. Each item was scored on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from “none of the time” to “all of the time.” The items were averaged to create a scale score (from 1 to 5), with higher values representing greater stigma. The scale showed acceptable internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.80).

Other Explanatory Variables

Sociodemographic variables included age, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, annual household income, health insurance status, risk/gender group, and HIV transmission risk category. Educational attainment was dichotomized into participants who had less than high school education, and those who had completed high school or equivalent. Individual annual income was dichotomized at $10,000 or less and greater than $10,000, with the cutoff based on the median income of the sample. Health insurance status was categorized into private insurance, public insurance, and no insurance. We assigned participants to mutually exclusive categories of HIV transmission risk [50]—men who have sex with men, men who have sex with women, or people who used injection drugs—with an additional category for transgender women given their unique risk related to HIV [51, 52]. We also included SF-12 mental health composite scores [53].

Statistical Analysis

The scales for life chaos, social support, and HIV-related stigma were centered by subtracting the sample mean from scores.

We used logistic regression analyses to estimate the dichotomous outcomes: HIV diagnosis while incarcerated, engagement in care prior to incarceration, and viral suppression. We used linear regression analysis for level of ART adherence. We examined factors associated with HIV diagnosis while incarcerated among all participants (N = 356) and examined correlates of the three remaining outcomes only among participants who were diagnosed with HIV prior to the current incarceration (N = 321). We first conducted bivariate regression analyses to estimate the association between HIV continuum outcomes and each of the variables described above. We then conducted multivariable analyses in which each HIV care continuum outcome was specified as a function of the explanatory variables described above. As an alternative way to interpret the logistic regression models [54], we estimated marginal effects, defined as the effect of a small change in life chaos on the probability of achieving HIV care continuum outcomes [55]. The regression models were fitted to complete-case data.

We also conducted sensitivity analysis by adding several variables to the regression models for each dependent variable to examine their effect on the previously observed associations. First, we added the interaction variables: life chaos × social support and life chaos × stigma, into separate multivariable models. We used these interaction variables to examine whether the associations between life chaos and HIV care continuum outcomes changed by the level of social support and the level of stigma, respectively. In separate multivariable models, we added CD4 count as sensitivity analyses. Because the estimates for the main independent variables were robust to this change, we present the original models with the primary independent variables and covariates as described above. Finally, we conducted sensitivity analysis using multiple imputation for the 90 missing (nonresponse) ART adherence values among those who were prescribed ART prior to incarceration by creating 10 imputed data sets using the multivariate normal (MVN) distribution command in STATA v.15.0.

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS v9.4; marginal effect estimates for logistic regression models and multiple imputation procedures were conducted using STATA v15.0 [56].

Results

Participant Characteristics

We interviewed 356 participants. One hundred and fifty-one (42%) participants were Black/African American and 110 (31%) were Hispanic/Latino (Table 1). The median age of the respondents was 40. Most respondents were MSM (56%), 37% did not graduate from high school, 42% earned $10,000 or less annually, 55% had no health insurance, and 11% had CD4 count less than 500. Regarding HIV care continuum outcomes (Table 2), 172 (48%) participants were diagnosed while incarcerated, of which 35 (20%) were diagnosed during this incarceration. Of the participants who were diagnosed prior to this incarceration, 46 (14%) had engaged in care in the past 12 months, and 218 (68%) were virologically suppressed at the time of incarceration. Among the 318 (89%) participants who were prescribed ART prior to incarceration, the mean self-reported percentage of ART adherence was 65%. The mean (standard deviation) for the scales (scored from 1 to 5) were as follows: life chaos 3.25 (1.29), social support 2.65 (0.86), and HIV-related stigma 2.59 (0.79).

Correlates of HIV Diagnosis While Incarcerated

In bivariate analyses, life chaos (OR = 1.35, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.73) was associated with higher odds of having been diagnosed with HIV while incarcerated, while having completed high school (OR = 0.62, 95% CI 0.41 to 0.96), and having public health insurance compared to having no insurance (OR = 0.60, 95% CI 0.39 to 0.92) were associated with lower odds (Table 3). In the multivariable model, life chaos (aOR = 1.52, 95% CI 1.09 to 2.11) was associated with higher odds of having been diagnosed with HIV while incarcerated, while having completed high school was associated with lower odds (aOR = 0.54, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.80). Average marginal effects estimates showed that a 1-point increase on the chaos scale increases the probability of diagnosis while incarcerated by about 10 percentage points; for example, increasing chaos from 3 to 4 on the 5-point scale would change this probability from 51 to 61%.

Correlates of Engagement in Care Prior to Incarceration

In bivariate analyses, life chaos (OR = 0.56, 95% CI 0.39 to 0.81) and Hispanic/Latino ethnicity (OR = 0.38, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.93) were associated with lower odds of engagement in care prior to entering jail, while older age (OR = 1.05, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.09), annual income over $10,000 (OR = 3.15, 95% CI 1.50 to 6.61), and having public (OR = 2.57, 95% CI 1.21 to 5.57) or private health insurance (OR = 7.09, 95% CI 2.87 to 17.51) versus no health insurance were associated with higher odds (Table 3). In the multivariable model, life chaos remained associated with lower odds of engagement in care prior to incarceration (aOR = 0.53, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.87), as did older age (aOR = 1.06, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.10), while annual income over $10,000 (aOR = 2.30, 95% CI 1.01 to 5.23), and private health insurance (aOR = 5.59, 95% CI 2.04 to 15.29) were associated with higher odds. Average marginal effects estimates showed that a 1-point increase on the chaos scale decreases the probability of engagement in care prior to entering jail by about 6 percentage points; for example, increasing chaos from 3 to 4 on the 5-point scale would change this likelihood from 9.5 to 5.6%.

Correlates of Antiretroviral Therapy Adherence

In bivariate analyses, life chaos (b = − 12.39, 95% CI − 18.90 to − 5.89), HIV-related stigma (b = − 8.10, 95% CI − 14.97 to − 1.23), being a man who has sex with men (b = − 16.21, 95% CI − 30.81 to − 1.61) and having public health insurance (b = − 12.53, 95% CI − 24.37 to − 0.69) were associated with lower ART adherence. The SF-12 mental component score (b = 0.54, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.99) was associated with higher ART adherence (Table 4). In the multivariable model, life chaos (b = − 8.68, 95% CI − 16.90 to − 0.46) was associated with lower ART adherence, representing an almost 9% decrease in self-reported adherence per one-point increase in the life chaos scale. Other covariates associated with lower ART adherence were being a man who has sex with men (b = − 17.68, 95% CI − 34.65 to − 0.70), and having public health insurance (b = − 14.28, 95% CI − 26.09 to − 2.47) compared to no insurance.

Sensitivity analysis using multiple imputation of ART adherence is shown in Appendix Table 5. Results of bivariate analyses using imputed data and non-imputed data were similar in magnitude and direction, with the exception of identifying as a transgender woman being associated with lower ART adherence in the analysis using imputed data. Results of the multivariable models using imputed data and non-imputed data were similar in magnitude and direction, with the exception of having public health insurance being not associated with ART adherence at the level of p < 0.05 in the model using imputed data.

Correlates of Virologic Suppression at Incarceration

In bivariate analyses, HIV-related stigma (OR = 0.69, 95% CI 0.51 to 0.93) was associated with lower odds, and SF12 mental component score (OR = 1.03, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.05) was associated with higher odds of virologic suppression (Table 3). In the multivariable model, Black/African American race remained associated with lower odds of virologic suppression (aOR = 0.47, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.93). Life chaos was not significantly associated with virological suppression.

Additional sensitivity analysis containing life chaos × social support and life chaos × HIV-related stigma interaction variables for multivariable logistic models, and multivariable linear regression models with complete case and multiple imputation for ART adherence are shown in Appendix Tables 6 and 7. The main effects of life chaos on HIV diagnosis while incarcerated, engagement in care, and ART adherence remained robust to the inclusion of these variables.

Discussion

While correctional facilities represent an important opportunity to address the HIV care continuum among vulnerable populations [57, 58], our study among cisgender men and transgender women PLH in the LA county jail showed significant gaps in the HIV care continuum prior to and upon entry into incarceration. Life chaos—the perception of having an unstable, unpredictable, disorganized life—was associated with elevated odds of HIV diagnosis while incarcerated among all participants, and with reduced odds of engagement in care and lower ART adherence among participants who were already diagnosed with HIV. However, our study did not support the hypothesized association between life chaos and viral suppression. The substantial associations of life chaos with several HIV care continuum variables remained significant and robust to the inclusion of multiple covariates that reflected the social environment of this vulnerable group of PLH.

Consistent with our hypotheses, life chaos was associated with greater odds of being first diagnosed with HIV while incarcerated. Almost half of our participants were diagnosed with HIV during their current or a prior incarceration rather than through targeted or routine testing in the community, reflecting the concentration of medically-underserved individuals in the criminal justice system [58]. Routine HIV screening is critical not only for timely linkage to care and treatment for PLH, but also for reducing unrecognized transmission of HIV to others in the community [39]. HIV screening for those who are seronegative can also provide opportunities for risk assessment, counseling and further interventions such as pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent acquisition of HIV [59].

Further consistent with our hypotheses, life chaos was associated with poor engagement in care, which was common in this vulnerable population. Eighty-five percent of the participants who had known HIV infection had not engaged in care in the community during the 12 months prior to incarceration, similar to findings from a recent systematic review on incarcerated PLH [7].

In addition, each one-point increase in the life chaos scale was associated with a 9% decrease in ART adherence in the 30 days prior to jail entry, a finding that was reproducible in the multiple imputation sensitivity analysis. The self-reported mean ART adherence was 65% among those with known HIV infection and prescribed ARTs, comparable to levels reported in other studies [7].

In contrast, life chaos was not statistically significantly associated with virologic suppression. While we do not know why this occurred in our study, one possible explanation may be that virologic suppression, especially when measured using a single measurement [60], is a downstream outcome that is not sensitive to the effects of upstream processes of engagement in care and adherence. Hence, life chaos may correlate with poor engagement in care and adherence to ART, but these processes may not be ultimately reflected in the viral load. First, virologic suppression is seen among patients with significant care gaps. In our study, among those who were diagnosed with HIV prior to this incarceration, 14% were engaged in care, while 68% were virologically suppressed. A recent study demonstrated a similar apparent discrepancy: a care gap of less than nine months had no association on viral load, and a gap of 12 months or more resulted in a quarter of previously suppressed patients becoming unsuppressed [61]. One explanation for this observation is that patients continue to take ART despite not engaging in care: a recent study based on a billings claim database showed that 40% of people with care gaps over six months continued to fill their ART prescriptions [62]. Furthermore, studies have shown that moderate levels of adherence as low as 75% can lead to virologic suppression [63,64,65]. Finally, reincarceration is common [66]. It is possible that participants received care and took ART during a previous jail stay within the 12 months prior to the current incarceration, and this may not have been reflected in the survey results.

While life chaos is an underexplored concept, the literatures on some related concepts may shed light to potential mechanisms through which life chaos may be linked to care continuum outcomes. The perception that the future is uncertain is a central component of life chaos; similarly, time preference theory proposes that those who perceive that the future is uncertain are less likely to engage in healthy behaviors, because they do not value the potential health benefit in the future [67]. If chaos in effect measures future uncertainty, the association we found between chaos and HIV testing, engagement in care, and ART adherence may reflect our participants’ lack of perceived benefit of these health-promoting activities. Another conceptually similar measure, stressful life circumstances (such as employment difficulties and major financial problems) predicted poor ART adherence [68]. Finally, life chaos has been closely linked to underlying poverty [13] as well as with unmet needs in housing, finances, employment, and food security [12, 58]. Prior studies showed that incarcerated PLH who are homeless [2, 69] or otherwise have difficulty meeting basic needs [57, 70] are less likely to receive routine HIV care. Homelessness [66, 69] and food insecurity have been associated with poor ART adherence [3], while employment has been associated with increased adherence [2] for incarcerated PLH.

After adjusting for covariates, we did not find any statistically significant differences in any of the HIV care continuum variables between transgender women and cisgender men. A recent multi-site study among criminal-justice involved PLH similarly found no significant difference in ART adherence or viral suppression between cisgender men and transgender women [71]. The same study found that transgender women were more likely to engage in HIV transmission risk behaviors compare to cisgender men. Transgender women experience disproportionate burden of HIV [72], and risk behaviors may drive gender disparities among criminal justice-involved PLH.

Interpretation of our findings is subject to limitations. First, our data are cross-sectional, which limits our ability to make causal inferences. Second, the interview was done prior to release from jail, so some participants may incorrectly recall their history prior to incarceration. While the restrictive environment of incarceration [18] may color the participants’ recollection of life chaos prior to incarceration, our mean chaos score was similar to that found among under-resourced PLH in Los Angeles [12]. The data on HIV testing, engagement in care, and ART adherence are self-reported, and therefore subject to the challenges inherent to all studies using self-reported data. We did not collect data on prior incarceration. While interviews were conducted in a confidential manner, data may be biased with respect to the participants’ willingness to report poor adherence and engagement with care. Finally, our results may not generalize to populations outside of Los Angeles County.

Our findings have important implications for researchers, health care providers and policy makers. At the individual level, our findings demonstrate the potential benefit of novel approaches to understand and address life chaos for PLH who experience incarceration in order to achieve HIV care continuum goals. Health care providers may identify patients who show signs of life chaos, such as having difficulty keeping their appointments or reluctance to schedule their next appointment, and offer supportive services, especially if they have experienced incarceration. Providers could partner with peer navigators or community health workers who may assist PLH in managing their life chaos, such as by scheduling or reminding them of their appointments or organizing transportation [38], thereby making health care a source of stability in their lives. It will be critical to identify and address life chaos among PLH prior to their arriving in jail. It will be important to examine whether interventions that target the underlying factors associated with life chaos, such as housing, food, and income will change the perceptions of insecurity and uncertainty among vulnerable people, and also lead to better continuum of care outcomes in well-designed prospective studies. At the community level, this may include addressing incarceration stigma—shame and discrimination of people who experience incarceration [57, 73, 74]—as this has been found be to a barrier for formerly incarcerated PLH to accessing care and other resources, such as housing, employment, and educational opportunities.

Despite these limitations, we conclude that, in this sample of cisgender men and transgender women incarcerated in a large municipal jail, life chaos was associated with gaps in the HIV care continuum prior to entering jail. Prospective studies, including intervention studies, will be needed to establish life chaos as a predictor of continuum outcomes. These findings underscore the value of addressing life chaos proximal to criminal justice involvement for PLH, which represents a public health and clinical target when addressing underlying structural issues faced by many PLH.

References

Maruschak LM, Bronson J. HIV in Prisons, 2015—Statistical Tables (NCJ 250641). Washington, DC: The U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics. August 2017.

Chitsaz E, Meyer JP, Krishnan A, et al. Contribution of substance use disorders on HIV treatment outcomes and antiretroviral medication adherence among HIV-infected persons entering jail. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(Suppl 2):S118–27.

Chen NE, Meyer JP, Avery AK, et al. Adherence to HIV treatment and care among previously homeless jail detainees. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(8):2654–66.

Eastment MC, Toren KG, Strick L, Buskin SE, Golden MR, Dombrowski JC. Jail booking as an occasion for HIV care reengagement: a surveillance-based study. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(5):717–23.

Meyer JP, Cepeda J, Wu J, Trestman RL, Altice FL, Springer SA. Optimization of human immunodeficiency virus treatment during incarceration: viral suppression at the prison gate. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(5):721–9.

Vagenas P, Zelenev A, Altice FL, et al. HIV-infected men who have sex with men, before and after release from jail: the impact of age and race, results from a multi-site study. AIDS Care. 2016;28(1):22–31.

Iroh PA, Mayo H, Nijhawan AE. The HIV care cascade before, during, and after incarceration: a systematic review and data synthesis. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(7):e5–16.

Pettit B, Western B. Mass imprisonment and the life course: race and class inequality in U.S. incarceration. Am Sociol Rev. 2004;69(2):151–69.

Blau JR, Blau PM. The cost of inequality: metropolitan structure and violent crime. Am Sociol Rev. 1982;47(1):114–29.

Wildeman C, Western B. Incarceration in fragile families. Future Child. 2010;20(2):157–77.

Matheny AP, Wachs TD, Ludwig JL, Kay P. Bringing order out of chaos: psychometric characteristics of the confusion, hubbub, and order scale. J Appl Dev Psychol. 1995;16(3):429–44.

Wong MD, Sarkisian CA, Davis C, Kinsler J, Cunningham WE. The association between life chaos, health care use, and health status among HIV-infected persons. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(9):1286–91.

Kalichman SC, Kalichman MO. HIV-related stress and life chaos mediate the association between poverty and medication adherence among people living with HIV/AIDS. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2016;23(4):420–30.

Crowley MJ, Zullig LL, Shah BR, et al. Medication non-adherence after myocardial infarction: an exploration of modifying factors. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(1):83–90.

Zullig LL, Shaw RJ, Crowley MJ, et al. Association between perceived life chaos and medication adherence in a postmyocardial infarction population. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(6):619–25.

Viswanath H, Wilkerson JM, Breckenridge E, Selwyn BJ. Life chaos and perceived social support among methamphetamine-using men who have sex with men engaging in transactional sexual encounters. Subst Use Misuse. 2017;52(1):100–7.

Shrage L. African Americans, HIV, and mass incarceration. Lancet. 2016;388(10049):e2–3.

Harawa NT, Amani B, Rhode Bowers J, Sayles JN, Cunningham W. Understanding interactions of formerly incarcerated HIV-positive men and transgender women with substance use treatment, medical, and criminal justice systems. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;48:63–71.

Kushel MB, Hahn JA, Evans JL, Bangsberg DR, Moss AR. Revolving doors: imprisonment among the homeless and marginally housed population. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(10):1747–52.

Chatterjee A, Gillman MW, Wong MD. Chaos, hubbub, and order scale and health risk behaviors in adolescents in Los Angeles. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2015;167(6):1415–21.

Wohl DA. HIV and mass incarceration: where infectious diseases and social justice meet. N C Med J. 2016;77(5):359–64.

McCarthy E, Myers JJ, Reeves K, Zack B. Understanding the syndemic connections between HIV and incarceration among African American men, especially African American men who have sex with men. In: Wright ER, Carnes N, editors. Understanding the HIV/AIDS Epidemic in the United States. Social Disparities in Health and Health Care. Springer, Cham; 2016. p. 217–40.

White Hughto JM, Reisner SL, Pachankis JE. Transgender stigma and health: a critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Soc Sci Med. 2015;147:222–31.

Reisner SL, Bailey Z, Sevelius J. Racial/ethnic disparities in history of incarceration, experiences of victimization, and associated health indicators among transgender women in the U.S. Women Health. 2014;54(8):750–67.

Krieger N. Epidemiology and the web of causation: has anyone seen the spider? Soc Sci Med. 1994;39(7):887–903.

Takada S, Weiser SD, Kumbakumba E, et al. The dynamic relationship between social support and HIV-related stigma in rural Uganda. Ann Behav Med. 2014;48(1):26–37.

Ransome Y, Kawachi I, Dean LT. Neighborhood social capital in relation to late HIV diagnosis, linkage to HIV care, and HIV care engagement. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(3):891–904.

Ransome Y, Batson A, Galea S, Kawachi I, Nash D, Mayer KH. The relationship between higher social trust and lower late HIV diagnosis and mortality differs by race/ethnicity: results from a state-level analysis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(1):1–9.

Hermanstyne KAG, Green HD Jr, Cook R, et al. Social Network Support and Decreased Risk of Seroconversion in Black MSM: Results of the BROTHERS (HPTN 061) Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018 Jun 1;78(2):163–8.

Scott HM, Pollack L, Rebchook GM, Huebner DM, Peterson J, Kegeles SM. Peer social support is associated with recent HIV testing among young black men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(5):913–20.

Rozanova J, Brown SE, Bhushan A, Marcus R, Altice FL. Effect of social relationships on antiretroviral medication adherence for people living with HIV and substance use disorders and transitioning from prison. Health Justice. 2015;3:18.

Kemnitz R, Kuehl TC, Hochstatter KR, et al. Manifestations of HIV stigma and their impact on retention in care for people transitioning from prisons to communities. Health Justice. 2017;5(1):7.

Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, Seeman TE. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(6):843–57.

Umberson D, Crosnoe R, Reczek C. social relationships and health behavior across life course. Annu Rev Sociol. 2010;36:139–57.

Sayles JN, Ryan GW, Silver JS, Sarkisian CA, Cunningham WE. Experiences of social stigma and implications for healthcare among a diverse population of HIV positive adults. J Urban Health. 2007;84(6):814–28.

Sayles JN, Wong MD, Kinsler JJ, Martins D, Cunningham WE. The association of stigma with self-reported access to medical care and antiretroviral therapy adherence in persons living with HIV/AIDS. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(10):1101–8.

Sayles JN, Wong MD, Cunningham WE. The inability to take medications openly at home: does it help explain gender disparities in HAART use? J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2006;15(2):173–81.

Cunningham WE, Weiss RE, Nakazono T, et al. Effectiveness of a peer navigation intervention to sustain viral suppression among HIV-positive men and transgender women released from jail: the LINK LA Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(4):542–53.

HIV Care Continuum. HIV.gov website. Available at: https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/policies-issues/hiv-aids-care-continuum. Updated December 30, 2016. Accessed 20 Jun 2018.

Buscher A, Hartman C, Kallen MA, Giordano TP. Validity of self-report measures in assessing antiretroviral adherence of newly diagnosed, HAART-naive, HIV patients. HIV Clin Trials. 2011;12(5):244–54.

Simoni JM, Huh D, Wang Y, et al. The validity of self-reported medication adherence as an outcome in clinical trials of adherence-promotion interventions: findings from the MACH14 study. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(12):2285–90.

Simoni JM, Kurth AE, Pearson CR, Pantalone DW, Merrill JO, Frick PA. Self-report measures of antiretroviral therapy adherence: a review with recommendations for HIV research and clinical management. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(3):227–45.

Loeliger KB, Altice FL, Desai MM, Ciarleglio MM, Gallagher C, Meyer JP. Predictors of linkage to HIV care and viral suppression after release from jails and prisons: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet HIV. 2018;5(2):e96–106.

Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. Department of Health and Human Services. Available at http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf. Accessed 31 Jul 2019.

Fleishman JA, Sherbourne CD, Crystal S, et al. Coping, conflictual social interactions, social support, and mood among HIV-infected persons. HCSUS Consortium. Am J Community Psychol. 2000;28(4):421–53.

Matsuzaki M, Vu QM, Gwadz M, et al. Perceived access and barriers to care among illicit drug users and hazardous drinkers: findings from the Seek, Test, Treat, and Retain data harmonization initiative (STTR). BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):366.

Chandler R, Gordon MS, Kruszka B, et al. Cohort profile: seek, test, treat and retain United States criminal justice cohort. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2017;12(1):24.

Sayles JN, Hays RD, Sarkisian CA, Mahajan AP, Spritzer KL, Cunningham WE. Development and psychometric assessment of a multidimensional measure of internalized HIV stigma in a sample of HIV-positive adults. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(5):748–58.

Cunningham W, Seiden D, Nakazono T, et al. Project LINK LA: potential mediators of peer navigation to link released HIV + jail inmates to HIV care; early results of an RCT Study. In: 11th international conference on HIV treatment and prevention adherence, Fort Lauderdale, FL. 2016.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2017; vol. 29. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Published November 2018. Accessed 31 Jul 2019.

Clark H, Babu AS, Wiewel EW, Opoku J, Crepaz N. Diagnosed HIV infection in transgender adults and adolescents: results from the national HIV surveillance system, 2009–2014. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(9):2774–83.

Lake JE, Clark JL. Optimizing HIV prevention and care for transgender adults. AIDS. 2019;33(3):363–75.

Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–33.

Ai C, Norton EC. Interaction terms in logit and probit models. Econ Lett. 2003;80(1):123–9.

Norton EC, Dowd BE. Log odds and the interpretation of logit models. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(2):859–78.

Williams R. Using the margins command to estimate and interpret adjusted predictions and marginal effects. Stata J. 2012;12(2):308–31.

Sidibe T, Golin C, Turner K, et al. Provider perspectives regarding the health care needs of a key population: HIV-infected prisoners after incarceration. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2015;26(5):556–69.

Rich JD. Correctional facilities as partners in reducing HIV disparities. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63(01):S49–53.

Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):399–410.

Marks G, Patel U, Stirratt MJ, et al. Single viral load measurements overestimate stable viral suppression among HIV patients in care: clinical and public health implications. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(2):205–12.

Gardner LI, Marks G, Patel U, et al. Gaps up to 9 months between HIV primary care visits do not worsen viral load. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2018;32(4):157–64.

Byrd KK, Bush T, Gardner LI. Do persons living with HIV continue to fill prescriptions for antiretroviral drugs during a gap in care? Analysis of a large commercial claims database. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2017;16(6):632–8.

Cheng Y, Sauer B, Zhang Y, et al. Adherence and virologic outcomes among treatment-naïve veteran patients with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Medicine. 2018;97(2):e9430.

Bangsberg DR. Less Than 95% adherence to nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor therapy can lead to viral suppression. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(7):939–41.

Nachega JB, Hislop M, Dowdy DW, Chaisson RE, Regensberg L, Maartens G. Adherence to nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-based HIV therapy and virologic outcomes effect of NNRTI-based HIV therapy adherence on HIV-1 RNA. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(8):564–73.

Clements-Nolle K, Marx R, Pendo M, Loughran E, Estes M, Katz M. Highly active antiretroviral therapy use and HIV transmission risk behaviors among individuals who are HIV infected and were recently released from jail. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(4):661–6.

Adams J. The role of time preference and perspective and socioeconomic inequalities in health-related behaviours. In: Babones SJ, editor. Social inequality and public health. Bristol: Policy Press; 2009.

Mugavero MJ, Raper JL, Reif S, et al. Overload: impact of incident stressful events on antiretroviral medication adherence and virologic failure in a longitudinal, multisite human immunodeficiency virus cohort study. Psychosom Med. 2009;71(9):920–6.

Zelenev A, Marcus R, Kopelev A, et al. Patterns of homelessness and implications for HIV health after release from jail. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(Suppl 2):S181–94.

Palar K, Wong MD, Cunningham WE. Competing subsistence needs are associated with retention in care and detectable viral load among people living with HIV. J HIV/AIDS Soc Serv. 2018;17(3):163–79.

Beckwith CG, Kuo I, Fredericksen RJ, et al. Risk behaviors and HIV care continuum outcomes among criminal justice-involved HIV-infected transgender women and cisgender men: data from the Seek, Test, Treat, and Retain Harmonization Initiative. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(5):e0197730.

Baral SD, Poteat T, Strömdahl S, Wirtz AL, Guadamuz TE, Beyrer C. Worldwide burden of HIV in transgender women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(3):214–22.

Schnittker J, John A. Enduring stigma: the long-term effects of incarceration on health. J Health Soc Behav. 2007;48(2):115–30.

Swan H. A qualitative examination of stigma among formerly incarcerated adults living with HIV. Sage Open. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244016667450.

Acknowledgements

Primary support for this research was provided by a grant from NIH/NIDA, R01 DA030781 (PI, Cunningham and Co-I Harawa). Additional support for time on this analysis (Shoptaw, Harawa, Cunningham) was provided by the Center for HIV Identification, Prevention, and Treatment (CHIPTS) NIMH grant MH58107, and NIH/NIDA, 1R01DA039934 (Harawa, Cunningham). Dr. Cunningham’s time was also supported in part by the University of California, Los Angeles and Charles Drew University, Resource Centers for Minority Aging Research Center for Health Improvement of Minority Elderly under NIH/NIA Grant P30-AG021684, the UCLA Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI) under NIH/NCATS grant UL1TR001881, the UCLA CTSI—NRSA Training Core grant TL1TR001883, and the National Institute of Health (NIH/NIR) R01NR017334. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the NIH. The authors also acknowledge salary support by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations through the National Clinician Scholars Program. The contents do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government. We would like to thank our participants and research assistants as well as our partners at the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health Mario Perez, Jennifer Sayles, Trista Bingham, Jane Rohde Bowers and Kim Bui, without whose contributions this study would not have been possible. We also thank Jimmy Ngo for his tireless administrative support. We thank Dr. Sonali Kulkarni for her involvement in the development, refinement, and oversight of the intervention. Finally, we recognize the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department for their support for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was obtained from University of California, Los Angeles Institutional Review Board and Department of Health and Human Services.

Informed Consent

All participants provided written informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: Key Measures

Appendix: Key Measures

-

A.

12-item Adult Confusion, Hubbub, and Order Scale (CHAOS)

-

B.

5-item social support scale

-

C.

12-item HIV-related stigma scale

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Takada, S., Ettner, S.L., Harawa, N.T. et al. Life Chaos is Associated with Reduced HIV Testing, Engagement in Care, and ART Adherence Among Cisgender Men and Transgender Women upon Entry into Jail. AIDS Behav 24, 491–505 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-019-02570-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-019-02570-0