Abstract

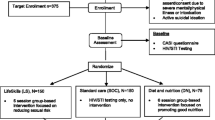

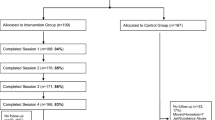

Culturally-specific HIV risk reduction interventions for Hispanic women are needed. SEPA (Salud/Health, Educación/Education, Promoción/Promotion, y/and Autocuidado/Self-care) is a culturally-specific and theoretically-based group intervention for Hispanic women. The SEPA intervention consists of five sessions covering STI and HIV prevention; communication, condom negotiation and condom use; and violence prevention. A randomized trial tested the efficacy of SEPA with 548 adult U.S. Hispanic women (SEPA n = 274; delayed intervention control n = 274) who completed structured interviews at baseline and 3, 6, and 12 months post-baseline. Intent-to-treat analyses indicated that SEPA decreased positive urine samples for Chlamydia; improved condom use, decreased substance abuse and IPV; improved communication with partner, improved HIV-related knowledge, improved intentions to use condoms, decreased barriers to condom use, and increased community prevention attitudes. Culturally-specific interventions have promise for preventing HIV for Hispanic women in the U.S. The effectiveness of SEPA should be tested in a translational community trial.

Resumen

Intervenciones culturalmente específicas son necesarias para la reducción de riesgo de contraer VIH en las mujeres hispanas. SEPA (Salud/Health, Educación/Education, Promoción/Promotion, y Autocuidado/Self-care) es una intervención grupal culturalmente específica con bases teóricas diseñada para mujeres Hispanas. La intervención SEPA consiste en cinco sesiones que cubren temas relacionados con la prevención de ITS - VIH, comunicación, negociación y uso del condón; y prevención de la violencia. Utilizando un estudio randomizado se probó la eficacia de SEPA con una muestra de 548 mujeres hispanas que viven en los Estados Unidos de Norteamérica (SEPA n = 274; grupo control n = 274). Las participantes respondieron una entrevistas estructuradas al inicio del estudio y a los 3, 6, y 12 meses posteriores a la intervención. Los resultados del análisis señalan que las mujeres que participaron en SEPA disminuyeron las muestras positivas de Chlamydia en orina, aumentaron el uso del condón, disminuyeron el abuso de sustancias y los episodios de violencia de pareja, mejoraron la comunicación de pareja, aumentaron el conocimiento sobre VIH, mejoraron la intención de utilizar condón, percibieron menores barreras para uso del condón, y mejoraron las actividades de prevención en la comunidad. Las intervenciones culturalmente específicas son promisorias para la prevención del VIH en las mujeres hispanas que viven en los Estados Unidos de Norteamérica. La efectividad de SEPA debe ser probada en la comunidad.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

World Health Organization. Women and health: today’s evidence, tomorrow’s agenda. 2009; Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2009/WHO_IER_MHI_STM.09.1_eng.pdf. Accessed 9 December 2010.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimates of new HIV infection in the United States. 2008; Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/factsheets/incidence.htm. Accessed 9 December 2010.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS among Hispanics/Latinos. 2010; Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/hispanics/resources/factsheets/pdf/hispanic.pdf Accessed 29 September 2011.

US Census Bureau. State & county quickfacts Miami-Dade County, Florida. Revised August 16, 2010; Available at: http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/12/12086.html. Accessed 9 December 2010.

Shedlin MG, Decena CU, Oliver-Velez D. Initial acculturation and HIV risk among new Hispanic immigrants. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97(7 Suppl):32S–7S.

Cianelli R, Ferrer L, McElmurry BJ. HIV prevention and low-income Chilean women: machismo, marianismo and HIV misconceptions. Cult Health Sex. 2008;10(3):297–306.

Gonzalez-Guarda RM, Peragallo N, Urrutia MT, Vasquez EP. HIV risk, substance abuse and intimate partner violence among Hispanic females and their partners. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2008;19(4):252–66.

Peragallo N. Latino women and AIDS risk. Public Health Nurs. 1996;13(3):217–22.

Campbell JC, Baty ML, Ghandour RM, Stockman JK, Francisco L, Wagman J. The intersection of intimate partner violence against women and HIV/AIDS: a review. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2008;15(4):221–31.

The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Women and HIV/AIDS in the United States: 2010. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats08/surv2008-Complete.pdf. Accessed 10 December 2010.

Dworkin SL, Ehrhardt AA. Going beyond “ABC” to include “GEM”: critical reflections on progress in the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):13–8.

UNESCO. A cultural approach to HIV/AIDS prevention and care: UNESCO/UNAIDS research project. 2002; Available at: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0012/001262/126289e.pdf. Accessed 9 December 2010.

U.S. Census Bureau. Health status, health insurance and health services utilization: 2001. 2006: Available at: http://www.census.gov/prod/2006pubs/p70-106.pdf. Accessed 7 July 2011.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Subset of best-evidence interventions, by characteristics. 2009; Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/research/prs/subset-best-evidence-interventions.htm. Accessed 1 July 2011.

El-Bassel N, Witte SS, Gilbert L, et al. The efficacy of a relationship-based HIV/STD prevention program for heterosexual couples. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(6):963–9.

Raj A, Amaro H, Cranston K, Martin B, Cabral H, Navarro A, et al. Is a general women’s health promotion program as effective as an HIV-intensive prevention program in reducing HIV risk among Hispanic women? Public Health Rep. 2001;116(6):599–607.

Amaro H, Raj A, Reed E, Cranston K. Implementation and long-term outcomes of two HIV intervention programs for Latinas. Health Promot Pract. 2002;3(2):245–54.

Martin M, Camargo M, Ramos L, Lauderdale D, Krueger K, Lantos J. The evaluation of a Latino community health worker HIV prevention program. Hispanic J Behav Sci 2005;27(3):371–84.

Harvey SM, Henderson JT, Thorburn S, Beckman LJ, Casillas A, Mendez L, et al. A randomized study of a pregnancy and disease prevention intervention for Hispanic couples. Perspect Sex and Reprod Health. 2004;36(4):162–9.

Peragallo N, Deforge B, O’Campo P, Lee SM, Kim YJ, Cianelli R, Ferrer L. A randomized clinical trial of an HIV risk reduction intervention among low-income Latina women. Nurs Res. 2005;54(2):108–18.

Choi KH, Hoff C, Gregorich SE, Grinstead O, Gomez C, Hussey W. The efficacy of female condom skills training in HIV risk reduction among women: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(10):1841–8.

Gonzalez-Guarda RM, Vasquez EP, Urrutia MT, Villarruel A, Peragallo N. Hispanic females’ experiences with substance abuse, intimate partner violence and risk for HIV. J Transcult Nurs. 2011;22(1):46–54.

Kim Y, Peragallo N, DeForge B. Predictors of participation in an HIV risk reduction intervention for socially deprived Latino women: a cross sectional cohort study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2006;43(5):527–34.

Bandura A. Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1977.

Cohen J. Statistical analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 1987.

Freire P. Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: Continuum; 1970.

Walker GT, Fraiser MS, Schram JL, Little MC, Nadeau JG, Malinowski DP. Strand displacement amplification—an isothermal, in vitro DNA amplification technique. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20(7):1691–6.

Straus MA, Douglas EM. A short form of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales, and typologies for severity and mutuality. Violence Vict. 2004;19(5):507–20.

Kelly JA, Murphy DA, Washington CD, et al. The effects of HIV/AIDS intervention groups for high-risk women in urban clinics. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(12):1918–22.

Catania JA, Binson D, Dolcini MM, et al. Risk factors for HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases and prevention practices among US heterosexual adults: changes from 1990 to 1992. Am J Public Health. 1995;85(11):1492–9.

Cianelli R. HIV/AIDS issues among Chilean Women: cultural factors and perception of risk for HIV/AIDS acquisition [dissertation]. University of Illinois at Chicago, Health Sciences Center; 2003

Heckman TG, Kelly JA, Sikkema K, et al. HIV risk characteristics of young adult, adult, and older adult women who live in inner-city housing developments: implications for prevention. J Womens Health 1995;4(4):397–406.

Sikkema KJ, Heckman TG, Kelly JA, et al. HIV risk behaviors among women living in low-income, inner-city housing developments. Am J Public Health. 1996;86(8):1123–8.

Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401.

Roberts RE, Vernon SW, Rhoades HM. Effects of language and ethnic status on reliability and validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale with psychiatric patients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1989;177(10):581–92.

Marin G, Gamba RJ. A new measurement of acculturation for Hispanics: the Bidimensional Acculturation Scale for Hispanic. Hispanic J Behav Sci. 1996;18(3):297–316.

Diggle PJ, Liang K, Zeger SL. Analysis of longitudinal data. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1994.

Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 5th ed. Los Angeles: Muthén and Muthén; 2007.

Pew Hispanic Center and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Hispanics and health care in the United States: Access, information and knowledge. 2004; Available at: http://www.pewhispanic.org/files/reports/91.pdf. Accessed 30 September 2011.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NCMHD) grant 1P60 MD002266—Center of Excellence for Health Disparities Research: El Centro, (Nilda P. Peragallo, Principal Investigator).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Peragallo, N., Gonzalez-Guarda, R.M., McCabe, B.E. et al. The Efficacy of an HIV Risk Reduction Intervention for Hispanic Women. AIDS Behav 16, 1316–1326 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-011-0052-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-011-0052-6