Abstract

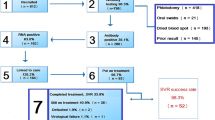

Accurate HCV knowledge is lacking among high-risk groups, including people with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA). Liver disease primarily due to HCV has emerged as a serious cause of mortality among PLWHA. We used an Interrupted Time Series design to evaluate a social-ecologically based intervention for PLWHA, where an infectious disease clinic serving a six-county intervention area was monitored before (7 months) and after (17 months) intervention onset. The intervention included education of PLWHA and medical providers, HIV/HCV support groups, and adaptation of the patient chart top sheet to include HCV test information. Clinic-level outcomes were assessed prospectively every other week for 2 years by interviewing patients (n = 259) with clinic appointments on assessment days. Abrupt, gradual and delayed intervention effects were tested. Weighted regression analyses showed higher average HCV knowledge and a higher prevalence of patients reporting HCV discussion with their medical providers after intervention onset. A delayed effect was found for HCV awareness, and a gradually increasing effect was found for knowing one’s HCV status. Other communities may consider adopting this intervention. Additional HCV interventions for PLWHA with HIV are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For all subsequent analyses, sensitivity analyses were conducted, where the same analyses were conducted with and without patients of American Indian/Alaskan Native background. The absence or presence of these patients did not alter substantive conclusion of the analyses, and thus the full sample analyses are reported here.

References

UNAIDS. Report on the global AIDS epidemic. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2008.

Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300(5):520–9.

Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, et al. Estimation of HIV incidence in the US. JAMA. 2008;300:520–9.

Armstrong GL, Wasley A, Simard EP, McQuillan GM, Kuhnert WL, Alter MJ. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1999 through 2002. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(10):705–14.

Vandelli C, Renzo F, Romano L, et al. Lack of evidence of sexual transmission of hepatitis C among monogamous couples: results of a 10-year prospective follow-up study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(5):855–9.

van de Laar TJ, van der Bij AK, Prins M, et al. Increase in HCV incidence among men who have sex with men in Amsterdam most likely caused by sexual transmission. J Infect Dis. 2007;196(2):230–8.

Verna EC, Brown RS. Hepatitis C virus and liver transplantation. Clin Liver Dis. 2006;10(4):919–40.

Rockstroh JK, Mocroft A, Soriano V, et al. Influence of hepatitis C virus infection on HIV-1 disease progression and response to highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2005;192(6):992–1002.

Lauer GM, Walker BD. Hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(1):41–52.

Sherman KE, Rouster SD, Chung RT, Rajicic N. Hepatitis C virus prevalence among patients infected with Human Immunodeficiency Virus: a cross-sectional analysis of the US adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;334:831–7.

Verucchi G, Calza L, Manfredi R, Chiodo F. Human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus coinfection: epidemiology, natural history, therapeutic options and clinical management. Infection. 2004;32(1):33–46.

Weber R, Sabin CA, Friis-Møller N, et al. Liver-related deaths in persons infected with the Human Immunodeficiency Virus: the D:A:D study. Ann Intern Med. 2006;166(15):1632–41.

Lima VD, Harrigan R, Bangsberg DR. The combined effect of modern highly active antiretroviral therapy regimens and adherence on mortality over time. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50(5):529–36.

Cribier B, Rey D, Schmitt C, Lang JM, Kirn A, Stoll-Keller F. High hepatitis C viraemia and impaired antibody response in patients coinfected with HIV. AIDS. 1995;9(10):1131–6.

Soriano V, Sulkowski M, Bergin C, et al. Care of patients with chronic hepatitis C and HIV co-infection: recommendations from the HIV-HCV International Panel. AIDS. 2002;16(6):813–28.

Sánchez-Quijano A, Andreu J, Gavilán F, et al. Influence of HIV type 1 infection on the natural course of chronic parenterally acquired hepatitis C. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;14(11):949–53.

Soto B, Sánchez-Quijano A, Rodrigo L, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus infection modified the natural history of chronic parenterally-acquired hepatitis C with an unusually rapid progression to cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 1997;26(1):1–5.

Bica I, McGovern B, Dhar R, et al. Increasing mortality due to end-stage liver disease in patients with Human Immunodeficiency Virus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32(3):492–7.

García-Samaniego J, Rodríguez M, Berenguer J, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in HIV-infected patients with chronic hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(1):179–83.

Rosenthal E, Poiree M, Pradier C, et al. Mortality due to hepatitis C-related liver disease in HIV-infected patients in France (Mortavic 2001 study). AIDS. 2003;17(12):1803–9.

Chou R, Clark M, Helfand M. Screening for hepatitis C virus infection: a review of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(6):465–79.

McGinn T, O’Connor-Monroe N, Alfandre D, Gardenier D, Wisnivesky J. Validation of a hepatitis C screening tool in primary care. AMA Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(18):2009–13.

Weaver MF, Cropsey KL, Fox SA. HCV prevalence in methadone maintenance: self-report versus serum test. Am J Health Behav. 2005;29(5):387–94.

Walley AY, White MC, Kushel MB, Song YS, Tulsky JP. Knowledge of and interest in hepatitis C treatment at a methadone clinic. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2005;28:181–7.

Carey J, Perlman DC, Friedmann P, et al. Knowledge of hepatitis among active drug injectors at a syringe exchange program. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2005;29:47–53.

Heimer R, Clair S, Grau LE, Blumenthal RN, Marshall PA, Singer M. Hepatitis-associated knowledge is low and risks are high among HIV-aware injection drug users in three US cities. Addiction. 2002;97:1277–87.

McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(4):351–77.

Stokols D. The social ecological paradigm of wellness promotion. In: Jamner MS, Stokols D, editors. Promoting human wellness: new frontiers for research, practice, and policy. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2000. p. 21–37.

Shadish W, Cook TD, Campbell D. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company; 2002.

Biglan A, Ary D, Wagenaar AC. The value of interrupted time-series experiments for community intervention research. Prev Sci. 2000;1(1):31–49.

Proeschold-Bell RJ, Heine A, Pence BW, McAdam K, Quinlivan EB. A cross-site, comparative effectiveness study of an integrated HIV and substance use treatment program. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2010;24(10):651–8.

Proescholdbell RJ, Blouin R, Reif S, et al. Hepatitis C transmission, prevention, and treatment knowledge among patients with HIV. South Med J. 2010;103(7):635–41.

Amemiya T. Tobit models: a survey. J Econom. 1984;24:3–61.

Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychol Methods. 2002;7(2):147–77.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National hepatitis C prevention strategy: a comprehensive strategy for the prevention and control of hepatitis C virus infection and its consequences. Division of Viral Hepatitis, National Center for Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2001. http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HCV/Strategy/NatHepCPrevStrategy.htm#summary. Accessed 6 Oct 2010.

National Institutes of Health. Management of hepatitis C. National Institutes of Health Consensus Conference Statement; 2002. http://consensus.nih.gov/2002/2002HepatitisC2002116html.htm. Accessed 27 Oct 2010.

Scott JD, Wald A, Kitahata M, et al. Hepatitis C Virus is infrequently evaluated and treated in an urban HIV clinic population. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2009;23(11):925–9.

Altice FL, Kamarulzaman A, Soriano VV, Schechter M, Friedland GH. Treatment of medical, psychiatric, and substance-use comorbidities in people infected with HIV who use drugs. Lancet. 2010;376:367–87.

Beyrer C, Malinowska-Sempruch K, Kamarulzaman A, Kazatchkine M, Sidibe M, Strathdee SA. Time to act: a call for comprehensive responses to HIV in people who use drugs. Lancet. 2010;376:551–63.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a grant from the Healthy Community Access Program (HCAP) of the Bureau of Primary Health Care, of the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (G92CSO2237-02-02). We thank F. Lombard, MSW, for his leadership on this study. We thank Elizabeth Goacher, PA, Duke University Department of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, for assisting with the development of the HCV knowledge items, Nathan Thielman, MD, MPH, Duke University Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Disease, for support in conducting research in the clinic, and Randall Pollard, LCSW, Duke Division of Infectious Disease, for assisting with participant recruitment and response rate data. The intervention could not have happened without Marc Kolman, Patrick Lee, Donna Tennyson, Teresa Hart, Xavier Purefoy, Betsy Barton, Robin Swift, Milford Evans, Tanya McNeill, and Kimberly Walker. We thank the many study interviewers, including Arit Amana, Christie Raulli, Carolyn Vance, Douglas Thomas, Josette Gbemudu, Sharon Abbruscato, and Brian Flores. Most importantly, we thank all the study participants.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Proeschold-Bell, R.J., Hoeppner, B., Taylor, B. et al. An Interrupted Time Series Evaluation of a Hepatitis C Intervention for Persons with HIV. AIDS Behav 15, 1721–1731 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-010-9870-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-010-9870-1