Abstract

This systematic review examines the overall efficacy of U.S. and international-based structural-level condom distribution interventions (SLCDIs) on HIV risk behaviors and STIs and identifies factors associated with intervention efficacy. A comprehensive literature search of studies published from January 1988 through September 2007 yielded 21 relevant studies. Significant intervention effects were found for the following outcomes: condom use, condom acquisition/condom carrying, delayed sexual initiation among youth, and reduced incident STIs. The stratified analyses for condom use indicated that interventions were efficacious for various groups (e.g., youth, adults, males, commercial sex workers, clinic populations, and populations in areas with high STI incidence). Interventions increasing the availability of or accessibility to condoms or including additional individual, small-group or community-level components along with condom distribution were shown to be efficacious in increasing condom use behaviors. This review suggests that SLCDIs provide an efficacious means of HIV/STI prevention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In most parts of the world, unprotected sex continues to be the leading cause of HIV infections [1]. In the United States, approximately 56,000 new HIV infections were diagnosed in 2006, and over 80% were attributed to unprotected sex [2, 3]. High-risk heterosexual contact accounted for 31% of the new cases, whereas unprotected sex among men who have sex with men accounted for 53% of the new cases [2, 3]. In the absence of an effective vaccine, protective behavior such as consistent and correct condom use continues to be the most effective strategy to reduce HIV transmission risk among sexually active heterosexual and MSM populations.

There are various existing approaches that promote condom use among people at high risk for sexual transmission of HIV. Individual-level interventions (ILI) and group-level interventions (GLI) directly address knowledge, attitudes, skills, and behaviors related to condom use in persons participating in intervention activities in one-on-one settings or in existing (e.g., couple, family) or newly formed groups. Community-level interventions (CLI) also directly and indirectly address knowledge, attitudes and behaviors with the focus on the entire community and often with a strong emphasis on changing social norms [4]. Evidence suggests that ILIs, GLIs, and CLIs demonstrate moderate to high success in promoting condom use [5]. Disseminating these types of interventions, however, may not be sufficient in combating the HIV epidemic, since they do not address the social and structural system or environments in which individuals reside. These contextual factors have been found to be a critical influence on individuals’ behaviors [6].

Structural-level interventions (SLIs) are particularly attractive in HIV prevention efforts since they are designed to address contextual factors that impact personal risk for HIV. Blankenship et al. proposed three structural-level intervention components that address behaviors of interest in public health: availability, accessibility, and acceptability [7]. When applied to HIV prevention tools such as condoms (see Table 1), SLIs target availability by making establishments responsible for the behaviors of their clients or for providing settings or materials that would reduce client risk [7]. Examples include placing condom bowls in clinics or 100% condom use policies in brothels. SLIs that target accessibility typically do so by making condoms and prevention messages widely accessible (e.g., massive distribution of free condoms at multiple venues simultaneously) without focusing on a specific establishment or client type. Increasing accessibility to condoms is a particularly attractive option for reaching marginalized populations in an effort to compensate for social inequities in access to prevention tools. SLIs target acceptability by changing social norms towards condoms (e.g., public service announcements about benefits of using condoms). These three SLI components can be directed to individuals, organizations, or the environment (Table 1). Combinations of these SLI components are likely to positively influence condom use behaviors since they are implemented in settings where individuals reside, an aspect frequently overlooked by existing ILIs, GLIs, and CLIs [7].

Previous reviews have focused mainly on evaluating ILIs, GLIs, and CLIs that address condom promotion (e.g., teaching individuals how to use a condom, promoting a positive attitude toward condoms, giving participants condoms to use after intervention) rather than larger-scale distribution [8, 9]. Johnson et al.’s meta-analysis of HIV risk reduction interventions among adolescents found that educational, psychosocial, or behavioral interventions advocating sexual risk reduction for HIV prevention were significantly more efficacious among intervention participants compared to participants in the control arm [8]. Although 18% of these interventions provided condoms as part of the intervention, nearly all also included provision of condoms for control participants as well. Findings from Smoak et al.’s meta-analysis showed that safer sex programs that provide condoms do not inadvertently increase sexual frequencies [9]. While those reviews are informative, the interventions evaluated in the reviews were limited to the small scale delivery (individual or group) and did not directly focus on or test structural-level approaches (i.e., improving availability, acceptability, and accessibility) in condom distribution programs.

The goals of this systematic review are to summarize the available research literature evaluating structural-level condom distribution interventions (SLCDIs), to meta-analyze quantitative data to assess the overall efficacy of SLCDIs on HIV-risk sex behaviors and sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and to assess whether structural-level intervention components (availability, accessibility, and acceptability) are associated with intervention efficacy. We also examine whether the level of implementation of SLI components (i.e., individual, organizational, or environmental) and the presence of any combination of additional ILI, GLI, or CLI components has a differential impact on the efficacy of SLCDIs. Additionally, we test whether intervention effects are applicable to various risk groups and to studies conducted in different countries or with different study designs.

Methods

Database and Search Strategy

We conducted various automatic and hand searches to ensure the inclusion of all the relevant citations. First, we searched the CDC HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis (PRS) project’s cumulative HIV/AIDS/STI prevention database that was developed to identify, review, and synthesize HIV/AIDS/STI intervention research literature published since 1988 [10, 11]. Automated systematic searches are conducted annually to update the PRS database using search terms (i.e. index terms, keywords, and proximity terms) cross-referenced in three areas: (a) HIV, AIDS, or STI; (b) intervention and prevention evaluation; and (c) behavior or biologic outcomes related to HIV infection or transmission (e.g., condom use, unprotected sexual partner, number of sex partners, STI and HIV incidence) [11]. This search is conducted each year in AIDSLINE (discontinued in 2000), EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and Sociological Abstracts, using the OVID search platform. Due to indexing gaps, a manual search of 35 key journals, which regularly publish HIV or STI prevention research, is performed quarterly to locate additional intervention reports. Second, we conducted a separate automated search in October, 2007 in MEDLINE, EMBASE, and PsycINFO using the keyword “condom” and various synonyms for the term “distribution” (e.g., access, disperse, market, provide, provision, promote, distribution, availability and dispense) to identify reports relevant to condom promotion and distribution. An additional supplemental search was later performed in the Cochrane Library for the keyword “condom” or “condoms”. CINAHL was considered for this review. However, prior testing of our more general annual PRS search proved significant overlap between CINAHL and the other databases and, thus, did not warrant a separate search. We also reviewed the reference list of all relevant studies to identify additional citations.

Study Selection

All citations retrieved through these searches were screened in October and November of 2007 for inclusion based on the following eligibility criteria. International and U.S.-based studies were included if they met all of the following criteria: (1) they reported on a HIV/AIDS/STI behavioral intervention that focused on condom distribution as a structural component that targeted acceptability, availability, or accessibility of condoms (defined in Table 1); (2) data were collected on at least one behavioral outcome (i.e., condom use, unprotected sex, number of sex partners, abstinence, sexual initiation, condom acquisition, or carrying a condom) or biological outcome (i.e., clinical or lab-confirmed HIV or STI diagnosis); (3) intervention effects were evaluated by comparing data from an intervention arm receiving a SLCDI and a comparison arm not receiving a SLCDI (from a randomized controlled trial (RCT) or non-randomized controlled trial), or data from independent cross-sectional samples assessed before and after implementation of a SLCDI; (4) English-language reports published from January 1988 through September 2007; and (5) sufficient data were available for calculation of effect sizes.

Data Abstraction and Quality Assessment

Information from eligible reports was independently coded by pairs of trained reviewers. Linkages among reports were identified to ensure that multiple reports describing an intervention were included in the coding and analyses. Using standardized coding forms, each intervention was coded for study characteristics (e.g., study location and dates), participant characteristics (e.g., target population, race/ethnicity, age, gender), and intervention characteristics (e.g., intervention components, delivery method, duration, and setting). For more specific coding of intervention components, we assessed (1) whether the structural component targeted the availability, acceptability, or accessibility of condoms (Table 1); (2) whether the structural component was implemented at the individual, organizational, and/or environmental level; and (3) whether the intervention was implemented at the individual-level (ILI), group-level (GLI), or community-level (CLI), in addition to the structural-level. We assessed the methodological quality by coding for study design, type of comparison, retention rates, and intent to treat. We examined study heterogeneity and implemented stratified analyses to assess intervention efficacy based on study quality as opposed to using a composite quality scale due to the potential problems in the interpretation of these scales [12].

The pairs of reviewers also independently abstracted data relevant to the outcomes of interest, reconciled all discrepancies, and if they could not reach an agreement, then a third independent reviewer helped resolve the discrepancy.

Analytic Approach and Meta-Analysis Methods

We used the following rules to guide the analytic data abstraction and effect size calculations. To ensure independence of effect sizes for studies with multiple arms, we selected the contrast between the most theoretically potent intervention arm and the comparison arm that was typically a standard of care or wait list control. For the condom use outcome, data from studies reporting unprotected sex were computed to reflect the percentage that ‘did not engage in unprotected sex’ in order to combine it with data from studies reporting condom use behavior. For studies that reported multiple follow-up assessments, we selected the longest post-intervention follow-up for assessing the longer-term intervention effect. We used data from adjusted models reported by the study authors for effect size calculation since such models typically control for baseline differences as well as potentially confounding variables. If adjusted data were not provided, and baseline data were reported, the effect sizes were calculated for the follow-up outcome data by adjusting for baseline differences [13].

Effect sizes (ES) for each study were estimated using odds ratio (OR) because the majority of the intervention studies compared two groups on a dichotomous outcome. The estimated OR for each study represents the intervention effect by estimating the relative odds of a particular outcome between the intervention and comparison arms [14]. For intervention studies that reported means and SD values on continuous outcomes, the standardized mean differences were computed and converted into OR values [13]. For condom use, condom acquisition, and delay in sexual initiation/abstinence, an OR > 1 indicates a greater increase in protective behavior in the intervention arm relative to the comparison arm. For number of sex partners and STD incidence, an OR < 1 indicates a greater reduction in the outcome in the intervention arm relative to the comparison arm.

The natural logarithm of the odds ratio (or lnOR) and its corresponding estimated variance were calculated for each study. In estimating the overall ES, across all studies, we multiplied each lnOR by its weight (or inverse variance), summed the weighted lnOR across studies and then divided by the sum of the weights. The aggregated lnOR was then converted back to OR by exponential function and a 95% confidence interval (95% CI) was derived to provide an overall intervention effect estimate across all studies.

We examined the magnitude of heterogeneity of the effect sizes by using both the Q statistic and Higgin’s I2 index to indicate the level of heterogeneity [15, 16]. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to determine whether the overall results were sensitive to the aforementioned rules used for guiding ES calculation. In particular, we examined whether intervention efficacy was impacted by any study by comparing the aggregated ES estimate among all studies with the estimate obtained after excluding a study or a set of studies that might influence the overall estimate.

Stratified analyses were conducted to examine the factors (e.g., intervention features) associated with the intervention effects of SLCDIs. These analyses focused only on condom use behaviors because of the greater relevance of condom use to HIV transmission and also because there were a sufficient number of studies reporting on this behavior. Stratification variables used to characterize the intervention included the type of structural component (e.g., availability, acceptability, or accessibility), the level of implementation of the structural-level component (e.g., individual, organizational, or environmental level), and whether or not any additional ILI, GLI, or CLI component was included as part of the SLCDI. We first conducted “marginal effects” analyses to examine the effects of each of the three types of structural components and each of the three levels of implementation regardless of how they were combined within a single intervention. We then assessed the combinations of types of structural components and levels of implementation. We also examined the impact of additional ILI, GLI, and CLI components within the intervention on condom use.

All overall and subgroup effect sizes and confidence intervals (Tables 3 and 4) were estimated using a random effects model. This model was used because it provides a more conservative estimate of variance and generates more accurate inferences about a population of trials beyond the set of trials included in this review [17]. Within the stratified analyses (Table 4), between-group differences were tested using a mixed-effects model with the QB between-group test statistic. The Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software (version 2) (Comprehensive Meta Analysis, 2005) was used to perform the analyses based on both random-effects and mixed-effects model.

Publication bias, which may favor studies with significant findings, was ascertained by inspection of a funnel plot of standard error estimates versus effect size estimates from individual samples and also by a linear regression test [14].

Results

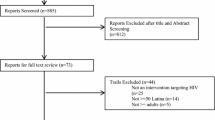

We identified 21 SLCDIs (Fig. 1; Table 2) [18–35]. Two-thirds of the studies were conducted in international settings (k = 14) [24–35], including 5 in Africa (2 in Tanzania, 2 in Cameroon, 1 in Ghana), 4 in East & Southeast Asia (2 in China, 1 in Indonesia, 1 in Thailand), 2 each in the Caribbean and Mexico, and 1 in Central America. Among the 7 studies conducted in the U.S. [18–23], two either specifically targeted (100%) or consisted of majority of African Americans (71.5%) and one specifically targeted Latinos; 2 studies consisted of majority of whites (75.4 and 51%) and the remaining 2 studies included mixed ethnic/racial groups.

Over one-third of the studies targeted commercial sex workers (CSWs) and either their clients or brothel managers (38%; k = 8) and all of these were implemented in international settings. Over one-third targeted youth and young adults (38%, k = 8), with an equal number of these studies conducted in the U.S. and international settings. The remaining studies targeted clinic patients (10%, k = 2), individuals in high STI areas (4%, k = 1), or adults in the general population (10%, k = 2). Among those studies that reported the participants’ age (k = 17), the median age across all study samples was 22 (range 15–65 years). Among the studies that reported participant gender, the majority either targeted (100%) or consisted of a majority of women (65%, k = 13). The majority of these were implemented in international settings (62%, k = 8).

Regarding intervention components, SLCDIs were implemented in the communities for an average of 10 months (range 4–24 months) for the U.S.-based studies and 15 months (range 6–42 months) for international studies. The majority of the U.S.-based studies typically addressed availability (k = 4), whereas the international studies typically implemented a combination of two or more SLCDI components within the intervention (k = 10). Additionally, the majority of both U.S. and international studies (14 out of 21) had additional ILI, GLI or CLI components. Reported outcomes of interest included condom use (k = 20), number of sex partners (k = 7), condom acquisition/condom carrying (k = 6), sexual initiation or abstinence (k = 5 youth studies), and STI infection (k = 5).

With regard to study design and quality, 10 studies (4 RCTs, 6 non-RCTs) evaluated SLCDI intervention effects by including a comparison arm not receiving a SLCDI. The median retention rate for these studies was 85.9% (range 40–99%) at the longest follow-up assessment (median: 6 months post-baseline for behavioral outcomes; 9.5 months post-baseline for biologic outcomes). All of these studies, except two, used an intent-to-treat approach for analysis (i.e., analyzed participants as originally assigned regardless of exposure). The remaining 11 studies evaluated intervention effects by comparing data from independent cross-sectional samples assessed before and after implementation of a SLCDI. For this subset, the median follow-up assessment time for behavioral outcomes was 14 months post-baseline and the median follow-up time for biologic outcomes was 17.5 months post-baseline.

Overall Effect Sizes for HIV-Risk Sex Behaviors and STI Outcomes

Before we combined effect sizes, we tested whether study design and study location (U.S. vs. international) were associated with the effect size estimates. There was no evidence of such association as significant intervention effects were observed for both U.S. and international studies and regardless of the type of study design. Thus, the effect sizes across studies were consequently aggregated.

As seen in Table 3, significant intervention effects were found for the following outcomes: increased condom use (OR = 1.81; 95% CI = 1.51, 2.17; P < .01; 20 studies; N = 23,574; Fig. 2); increased condom acquisition/condom carrying (OR = 5.40; 95% CI = 1.86, 15.66; P < .05; 6 studies; N = 3,304), delaying sexual initiation/abstinence among youth (OR = 1.43; 95% CI = 1.01, 2.03; P < .05; 5 studies; N = 6,692); and reduced incidence of STIs (OR = 0.69; 95% CI = 0.53, 0.91, P < .01; 5 studies; N = 2,196). There was no significant intervention effect observed for the number of sex partners (OR = 1.28; 95% CI = 0.89, 1.85; P > .18; 7 studies; N = 4,660). Both the I2 statistic and the Q statistic indicate considerable heterogeneity among studies. However, the sensitivity test of each outcome did not reveal any individual effect size that exerted influence on the overall heterogeneity.

To evaluate the presence of publication bias, we used linear regression methods to investigate funnel plot asymmetry. There was no evidence of publication bias for any of the relevant outcomes (all Ps > .05).

Stratified Analyses for Intervention Effects on Condom Use

To provide an overview of the pattern of findings, we present the findings on condom use from the combined data as well as findings stratified by study location (U.S.-based vs. international) in Table 4. Interventions conducted in U.S.-based and international settings were both efficacious in improving condom use behaviors (Table 4), however, significantly greater efficacy was found among interventions that were implemented in international settings (QB = 6.81, P < .05). Since the pattern of findings tended to be qualitatively similar across these settings, the summary below focuses on the combined data which can also allow for greater power in detecting an intervention effect.

The tests described below were based on a-prior hypotheses for the potential moderator effects. The I2 values for most of the stratified analyses (Table 4) remained in the moderate to high range. When comparing the I2 values reported in Table 4 and the I2 value for condom use reported in Table 3, some moderators were associated with reduced heterogeneity (e.g., combined availability, acceptability, and accessibility; specifically targeting high STD and clinic participants).

Several significant findings emerged when comparing intervention groups to comparison groups within each of the stratified analyses shown in Table 4. The significant intervention effects were seen in trials regardless of participants’ characteristics (i.e., specifically targeting youth, commercial sex workers, adults, high STD and clinic populations or males).

With regard to type of structural component (e.g., that which increased the availability, acceptability or accessibility of condoms), the marginal analyses revealed a significant positive effect on condom use for interventions that increased the availability of condoms (OR = 1.70; 95% CI = 1.39, 2.07; P < .01; k = 14). Similarly, significant positive intervention effects were also observed for interventions that increased acceptability of condoms (OR = 1.63; 95% CI = 1.33, 2.00; P < .01; k = 11) and for interventions that increased accessibility to condoms (OR = 2.30; 95% CI = 1.67, 3.17; P < .01; k = 11).

Assessing the combinations of structural components revealed a significant effect for interventions that implemented availability as a sole strategy (OR = 1.43; 95% CI = 1.21, 1.69; P < .01; k = 3), and also when availability was coupled with messages that promote the acceptability of condom use (OR = 1.64; 95% CI = 1.21, 2.21; P < .01; k = 6) or when availability was coupled with methods that increase accessibility to condoms (e.g., massive distribution of free condoms (OR = 6.68; 95% CI = 3.46, 12.90; P < .01; k = 2). Significant effects were also observed for interventions that focused on increasing accessibility to condoms as a sole strategy (OR = 2.70; 95% CI = 1.29, 5.63; P < .05; k = 4).

With regard to level of implementation (e.g., individual, organizational or environmental level), the marginal analyses revealed a significant positive effect on condom use for interventions implemented at the individual level (OR = 1.87; 95% CI = 1.55, 2.25; P < .01; k = 19). Significant positive intervention effects were also observed for interventions implemented at the organizational level (OR = 1.77; 95% CI = 1.34, 2.34; P < .01; k = 9) and for interventions implemented at the environmental level (OR = 1.87; 95% CI = 1.44, 2.42; P < .01; k = 6). When assessing the combination of the different levels of implementation, interventions implemented at the individual level only (OR = 2.01; 95% CI = 1.41, 2.88; P < .01; k = 8) or at the individual + organizational + environmental level (OR = 2.18; 95% CI = 1.28, 3.71; P < .01; k = 3) were both effective in increasing condom use behaviors.

An overall significant intervention effect was observed for solely structural-level (SLI only, with no ILI, GLI, or CLI components) interventions (OR = 1.35; 95% CI = 1.09, 1.69; P < .05; k = 7), as well as for structural-level interventions that also included either ILI/GLI (OR = 2.61; 95% CI = 1.76, 3.86; P < .05; k = 6), CLI (OR = 1.83; 95% CI = 1.72, 1.95; P < .05; k = 1), both ILI/GLI and CLI components (OR = 1.89; 95% CI = 1.07, 3.33; P < .05; k = 6), or any ILI/GLI or CLI components (OR = 2.13; 95% CI = 1.71, 2.66; P < .05; k = 13) (Table 4).

When comparing across the different subgroups of interventions to identify factors related to greater efficacy, several important factors emerged. Interventions that coupled SLCDIs with any additional ILI, GLI, or CLI components were associated with significantly greater efficacy than SLCDIs that solely implemented a structural-level component (QB = 8.10, P < .01). With regard to type of structural component, interventions that implemented availability or accessibility as sole strategies, as well as interventions that implemented availability + acceptability messages or availability + accessibility demonstrated significantly greater efficacy compared to all other types of SLCDIs (QB = 22.05, P < .01). With regard to level of implementation, SLCDIs that were implemented at the individual level or the individual + organizational + environmental level demonstrated significantly greater efficacy compared to all other types of SLCDIs (QB = 10.94, P < .05).

Discussion

This meta-analysis of 21 U.S. and international studies indicates that structural-level condom distribution interventions (SLCDIs), evaluated as a whole, are efficacious in reducing various HIV sex-risk behaviors and incident STIs. The magnitude of intervention effects observed here are comparable, and in most cases, stronger, than those reported in other meta-analyses that examined intervention effects on HIV risk among various populations [36–40]. Risk reduction of this magnitude is also well within the range considered to be cost-effective when translated into final health outcomes [41].

Several characteristics of SLCDIs contribute to intervention efficacy based on our analysis of condom use behaviors. For example, interventions consisting solely of a structural component (SLI only) are efficacious, while interventions that combine SLIs with additional individual, small group or community-level activities show even greater efficacy. One possible reason for the increased efficacy of combining multi-level intervention components is that these different modalities address various aspects of influencing factors (e.g., norms, knowledge, skills, motivation and access) as well as prevention needs of individuals in affected communities. Additionally, interventions that increased the availability of condoms, or increased accessibility to condoms, as a distribution strategy were efficacious in increasing condom use behaviors. Interestingly, no intervention used acceptability as the only strategy as acceptability was addressed in combination with availability and/or accessibility. There were also no SLCDIs that were implemented at the environmental level only. SLCDIs implemented at the individual level were found to be efficacious as well as SLCDIs implemented at all three levels (individual, organizational, and environmental).

With regard to applicability, it is very encouraging that SLCDIs promote condom use in various populations, such youth, adults, commercial sex workers, high STD populations and males. Our review further shows that SLCDIs targeting youth generally combined the SLI component with ILI/GLI components and focused on increasing the availability of condoms. Making condoms available at venues frequented by youth combined with ensuring that important prevention messages are relayed through individual and small group sessions is likely to result in greater condom use behaviors. Most importantly, our overall findings also show that SLCDIs have protective effects on sexual initiation among youth.

Commercial sex workers also benefitted from condom distribution programs. These interventions, from the international literature, targeted sex establishments (e.g., sex brothels) by trying to change the social and structural environment, in addition to making condoms more available or accessible. This finding is not too surprising because programs that aim to increase accessibility are designed to compensate for social inequities by making products more available for marginalized populations who may not have equal access to those resources (e.g., massive distribution of free condoms). In addition, creating an enabling environment through supportive policies and social norms around condom use may empower sex workers to refuse unprotected sex.

Several limitations of this meta-analysis warrant comment. Some of the more notable structural-level condom distribution programs in international settings were included in this review (e.g. 100% condom campaign in China [35]), however, several similar programs were not. A few 100% Condom Use Programs that have been conducted across many countries in Asia were excluded for various methodological reasons [42–46]. These reasons included study design issues (e.g., not reporting both pre-intervention and post-intervention data from independent cross-sectional samples or using a separate comparison group) or not providing sufficient data for meta-analyses (e.g., not providing sample sizes or variance estimates or citing unpublished data). These 100% Condom Use Programs have been successfully implemented throughout Asia over the years, and, in general, they have resulted in increases in condom use by commercial sex workers (CSWs) or their clients over time and declines in HIV/STD prevalence in the CSW community or the population as a whole [42–46]. The findings in our review are consistent with these results and we believe not including these did not bias our overall conclusions. Based on the framework proposed in our review (Table 1), these programs usually have addressed all three components (availability, acceptability, and accessibility) at all three levels (individual, organizational, and environmental) which also supports the notion that multi-level or multi-component condom distribution programs may have the strongest efficacy. Some common elements of these programs that may play a role in their success include providing political support, focusing on owners and managers of sex work establishments (e.g., brothels, bars), conducting public campaigns or social marketing campaigns to normalize condom use, making condoms more available or accessible, and obtaining organizational support [43, 47].

The current review is limited to English-language publications. A post hoc supplemental search using the same search protocol as described in the “Method” section indicated that only a handful of foreign language citations out of almost 300 identified were potentially relevant to this review. Upon further examination, only two were identified as new studies that would potentially meet eligibility criteria [48, 49]. Since we did not have the capacity to translate the full text of these reports to confirm eligibility, we believe our search missed at most two studies due to the language restriction during our review period. Based on the abstracts, both studies support condom distribution for HIV prevention.

We reviewed the HIV prevention literature through September 2007. Since completing this review, we have identified several newly published evaluations of condom distribution programs in other international settings and with different populations (e.g., men who have sex with men) that may be relevant to our review [50–58]. The recent emphasis by UNAIDS on national level comprehensive HIV prevention approaches aimed towards universal access to prevention, treatment, care and support for all those in need [59] has led to evaluations of these types of programs in various parts of the world [53–58]. Many of these comprehensive HIV prevention approaches have included wide-scale condom promotion and distribution in combination with other HIV/STD prevention efforts, such as STD care or sexual health care. Our findings do support the 2007 UNAIDS Guidelines Toward Universal Care in the UNAIDS, which recommends universal and uninterrupted condom availability and integrated condom promotion into other health services as part of a comprehensive HIV prevention approach [59]. These recently published studies could build upon the evidence summarized in this review to better understand what works, how it works, in what settings, and with what populations.

We observed moderate to high levels of heterogeneity among studies, even after conducting stratified analyses. We initially attempted to conduct a multivariate random-effects metaregression analysis including covariates for the type of structural component, level of implementation, and additional intervention components in an effort to identify independent predictors of intervention effects. Given the small number of studies in our review, and the concern for multicollinearity across variables, the findings were difficult to interpret and, thus, not presented. The studies included in this review are heterogeneous in terms of target group, intervention components, level of implementation, and study design. Although the heterogeneity was not substantially reduced with the univariate stratified analyses, our findings do support overall efficacy of SLCDIs and point to important directions for future consideration.

First, the remaining heterogeneity does suggest that additional factors related to efficacy, beyond those considered in this review, may exist. Our findings suggest that addressing availability, accessibility, or acceptability, as key barriers to condom use, does increase condom use. However, these programs do employ a variety of delivery methods, implementation strategies, or operational techniques in order to promote and distribute condoms. Questions related to implementation, such as how condoms were distributed, who distributed condoms, where they were distributed, duration of the program, types of social marketing, who delivered messages, additional services provided, etc., were beyond the scope of this review. Exploring these types of questions in future reviews can help to improve program implementation.

Second, condom distribution programs can significantly impact condom use behaviors among at-risk populations (e.g., youth, adults), as well as high-risk populations (e.g., commercial sex workers). Given the efficacy of these programs on condom use as well as STD incidence, future research should explore how other high-risk populations that are disproportionately affected by HIV and other STDs, such as African Americans, MSM and those in correctional facilities, may also benefit from such programs. It would also be important to include cost analyses to determine how the programs can be most effectively and efficiently delivered.

Finally, more than half of the studies included in our review were conducted in international settings, and those interventions were found to be significantly more efficacious than those conducted in the U.S. This finding suggests that much can be gained by understanding what makes those condom distribution programs more efficacious. Several evaluations of structural-level condom distribution programs, particularly in the international setting, have been published since conducting this review that could build upon the evidence summarized here to better understand the differences between the U.S. and international programs. Identifying effective strategies in one setting could also inform how to adapt and implement programs for different target populations or in new settings.

This systematic review supports the structural-level condom distribution intervention as an efficacious approach to increasing condom use and reducing HIV/STD risk. Given the urgency of the HIV epidemic, making condoms more universally available, accessible, and acceptable, particularly in communities or venues reaching high-risk individuals, should be considered in any comprehensive HIV/STD prevention program. Further exploration around how best to implement condom distribution programs to maximize their reach and impact should be considered.

References

UNAIDS. The 2006 AIDS epidemic update. Available at http://www.unaids.org/en/KnowledgeCentre/HIVData/EpiUpdate/EpiUpdArchive/2006. Accessed 5 Nov 2009.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimates of new HIV infections in the United States. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease and Control. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/factsheets/pdf/incidence.pdf Accessed 1 July 2009.

Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, et al. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300(5):520–9.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Evolution of HIV/AIDS prevention programs—United States, 1981–2006. MMWR. 2006;55(21):597–603.

Noar S. Behavioral interventions to reduce HIV-related sexual risk behavior: review and synthesis of meta-analytic evidence. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(3):335–53.

Wohlfeiler D, Ellen JM. The limits of behavioral interventions for STD/HIV prevention. In: Cohen L, Chavez V, Chemini S, editors. Prevention is primary: strategies for community well-being. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2008. p. 329–47.

Blankenship KM, Bray SJ, Merson MH. Structural interventions in public health. AIDS. 2000;14(Suppl 1):S11–21.

Johnson BT, Carey MP, Marsh KL, Levin KD, Scott-Sheldon LA. Interventions to reduce sexual risk for the human immunodeficiency virus in adolescents, 1985–2000: a research synthesis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(4):381–8.

Smoak ND, Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Johnson BT, Carey MP. Sexual risk reduction interventions do not inadvertently increase the overall frequency of sexual behavior: a meta-analysis of 174 studies with 116, 735 participants. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41(3):374–84.

Lyles CM, Crepaz N, Herbst JH, Kay L, for the HIV/AIDS Research Synthesis (PRS) Project. Evidence-based HIV behavioral prevention from the perspective of CDC’s HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis Team. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006;18(4 Suppl A): S21–31.

DeLuca JB, Mullins MM, Lyles C, Crepaz N, Kay LS, Thadiparti S. Developing a comprehensive search strategy for evidence-based systematic review. Evid Based Libr Inf Prac. 2008;3(1):3–32.

Juni P, Altman DG, Egger M. Assessing the quality of randomized controlled trials. In: Egger M, Smith GD, Altman DG, editors. Systematic reviews in health care: meta-analysis in context. London: BMJ; 2001. p. 87–108.

Johnson WD, Semaan S, Hedges LV, Ramirez G, Mullen PD, Sogolow E. A protocol for the analytical aspects of a systematic review of HIV prevention research. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;30(Suppl 1):S62–72.

Lipsey MW, Wilson DB. Practical meta-analysis. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications; 2001.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–58.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Br Med J. 2003;327(7414):557–60.

Hedges L, Vevea J. Fixed and random effects models in meta-analysis. Psychol Methods. 1998;3(4):486–504.

Alstead M, Campsmith M, Halley CS, Hartfield K, Goldbaum G, Wood RW. Developing, implementing, and evaluating a condom promotion program targeting sexually active adolescents. AIDS Educ Prev. 1999;11(6):497–512.

Blake SM, Ledsky R, Goodenow C, Sawyer R, Lohrmann D, Windsor R. Condom availability programs in Massachusetts high schools: relationships with condom use and sexual behavior. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(6):955–62.

Cohen DA, Dent C, MacKinnon D, Hahn G. Condoms for men, not women: results of brief promotion programs. Sex Transm Dis. 1992;19(5):245–51.

Cohen DA, Farley TA, Bedimo-Etame JR, et al. Implementation of condom social marketing in Louisiana, 1993 to 1996. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(2):204–8.

Schuster MA, Bell RM, Berry SH, Kanouse DE. Impact of a high school condom availability program on sexual attitudes and behaviors. Fam Plann Perspect. 1998;30(2):67–72.

Sellers DE, McGraw SA, McKinlay JB. Does the promotion and distribution of condoms increase teen sexual activity? Evidence from an HIV prevention program for Latino youth. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(12):1952–8.

Asamoah-Adu A, Weir S, Pappoe M, Kanlisi N, Neequaye A, Lamptey P. Evaluation of a targeted AIDS prevention intervention to increase condom use among prostitutes in Ghana. AIDS. 1994;8(2):239–46.

Egger M, Pauw J, Lopatatzidis A, Medrano D, Paccaud F, Smith GD. Promotion of condom use in a high-risk setting in Nicaragua: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;355(9221):2101–5.

Ford K, Wirawan DN, Fajans P, Meliawan P, MacDonald K, Thorpe L. Behavioral interventions for reduction of sexually transmitted disease/HIV transmission among female commercial sex workers and clients in Bali, Indonesia. AIDS. 1995;10(2):213–22.

Kerrigan D, Moreno L, Rosario S, et al. Environmental-structural interventions to reduce HIV/STI risk among female sex workers in the Dominican Republic. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(1):120–5.

Laukamm-Josten U, Mwizarubi BK, Outwater A, et al. Preventing HIV infection through peer education and condom promotion among truck drivers and their sexual partners in Tanzania, 1990–1993. AIDS Care. 2000;12(1):27–40.

Martinez-Donate AP, Hovell MF, Zellner J, Sipan CL, Blumberg EJ, Carrizosa C. Evaluation of two school-based HIV prevention interventions in the border city of Tijuana, Mexico. J Sex Res. 2004;41(3):267–78.

Meekers D, Agha S, Klein M. The impact on condom use of the “100% Jeune” social marketing program in Cameroon. J Adolesc Health. 2005;36(6):530.e1–12.

Mhalu F, Hirji K, Ijumba P, et al. A cross-sectional study of a program for HIV infection control among public house workers. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1991;4(3):290–6.

Sakondhavat C, Werawatanakul Y, Bennett A, Kuchaisit C, Suntharapa S. Promoting condom-only brothels through solidarity and support for brothel managers. Int J STD AIDS. 1997;8(1):40–3.

Van Rossem R, Meekers D. An evaluation of the effectiveness of targeting social marketing to promote adolescent and young adult reproductive health in Cameroon. AIDS Educ Prev. 2000;12(5):383–404.

Xiaoming S, Yong W, Choi K, Lurie P, Mandel J. Integrating HIV prevention education into existing family planning services: results of a controlled trial of a community-level intervention for young adults in rural China. AIDS Behav. 2000;4(1):103–10.

Zhongdan C, Schilling RF, Shanbo W, Caiyan C, Wang Z, Juanguo S. The 100% condom use program: a demonstration in Wuhan, China. Eval Program Plann. 2008;31(1):10–21.

Neumann MS, Johnson WD, Semaan S, et al. Review and meta-analysis of HIV prevention intervention research for heterosexual adult populations in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;30(Suppl 1):S106–17.

Mullen PD, Ramirez G, Strouse D, Hedges LV, Sogolow E. Meta-analysis of the effects of behavioral HIV prevention interventions on the sexual risk behavior of sexually experienced adolescents in controlled studies in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;30(Suppl 1):S94–105.

Crepaz N, Horn AK, Rama SM, et al. The efficacy of behavioral interventions in reducing HIV risk sex behaviors and incident sexually transmitted disease in Black and Hispanic sexually transmitted disease clinic patients in the United States: a meta-analytic review. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34(6):319–32.

Darbes L, Crepaz N, Lyles C, Kennedy G, Rutherford G. The efficacy of behavioral interventions in reducing HIV risk behaviors and incident sexually transmitted diseases in heterosexual African Americans. AIDS. 2008;22(10):1177–94.

Crepaz N, Marshall K, Aupont L, et al. The efficacy of HIV/STI behavioral interventions for African American females in the United States: a meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(11):1–11.

Holtgrave DR. Estimating the effectiveness and efficiency of U.S. HIV prevention efforts using scenario and cost-effectiveness analysis. AIDS. 2002;16(17):2347–9.

Celentano D, Nelson KE, Lyles CM, et al. Decreasing incidence of HIV and sexually transmitted diseases in young Thai men: evidence for success of the HIV/AIDS control and prevention program. AIDS. 1998;12(5):F29–36.

Rojanapithayakorn W. The 100% condom use programme in Asia. Reprod Health Matters. 2006;14(28):41–52.

World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Office for the Western Pacific. 100% condom use programme: experience from China (2001–2004). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2004. Available from http://www.wpro.who.int/internet/resources.ashx/HSI/docs/100CUP(China)2.pdf. Accessed 27 Aug 2010.

World Health Organization Regional (WHO) Office for the Western Pacific. Experiences of 100% condom use programme in selected countries of Asia. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2004. Available from http://www.wpro.who.int/publications/pub_9290610921.htm. Accessed 27 Aug 2010.

World Health Organization Regional (WHO) Office for the Western Pacific. 100% condom use programme: experience from Mongolia. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2005. Available from http://www.wpro.who.int/internet/resources.ashx/HSI/docs/100CUP(Mongolia).pdf. Accessed 27 Aug 2010.

World Health Organization Regional (WHO) Office for the Western Pacific. Joint UNFPA/WHO meeting on the 100% condom use programme. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2006. Available from http://www.wpro.who.int/internet/resources.ashx/HSI/report/MtgRep_UNFPA_WHO_100CUP.pdf. Accessed 27 Aug 2010.

Paiva V, Pupo LR, Barboza R. The right to prevention and the challenges of reducing vulnerability to HIV in Brazil. Rev Saude Publica. 2006;40(Suppl):109–19.

Yang F, Wu Z, Xu C. Acceptability and feasibility of promoting condom use among families with human immunodeficiency virus infection in rural area of China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2001;22(5):330–3.

Ko NY, Lee HC, Hung CC, et al. Effects of structural intervention on increasing condom availability and reducing risky sexual behaviours in gay bathhouse attendees. AIDS Care. 2009;21(12):1499–507.

Zhang HB, Zhu JL, Wu ZY, et al. Intervention trial on HIV/AIDS among men who have sex with men based on venues and peer network. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2009;43(11):970–6.

Piot B, Mukherjee A, Navin D, et al. Lot quality assurance sampling for monitoring coverage and quality of a targeted condom social marketing programme in traditional and non-traditional outlets in India. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86(Suppl 1):i56–61.

Lowndes CM, Alary M, Labbé AC, et al. Interventions among male clients of female sex workers in Benin, West Africa: an essential component of targeted HIV preventive interventions. Sex Transm Infect. 2007;83(7):577–81.

Gregson S, Adamson S, Papaya S, et al. Impact and process evaluation of integrated community and clinic-based HIV-1 control: a cluster-randomised trial in eastern Zimbabwe. PLoS Med. 2007;4(3):e102.

Rou K, Wu Z, Sullivan SG, et al. A five-city trial of a behavioural intervention to reduce sexually transmitted disease/HIV risk among sex workers in China. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 8):S95–101.

Islam MM, Conigrave KM. HIV and sexual risk behaviors among recognized high-risk groups in Bangladesh: need for a comprehensive prevention program. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12(4):363–70.

Lipovsek V, Mukherjee A, Navin D, Marjara P, Sharma A, Roy KP. Increases in self-reported consistent condom use among male clients of female sex workers following exposure to an integrated behaviour change programme in four states in southern India. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86(Suppl 1):i25–32.

Murguia Pardo CR. Improving the access to male and female condoms in Peru as part of a comprehensive approach to achieve sexual behaviors changes. In: International AIDS conference 2010, Vienna, Austria, July 18–23, 2010 (abstract MOPE0294).

UNAIDS. 2007 UNAIDS’ practical guidelines for intensifying HIV prevention toward universal care. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/unaids/2007/9789291735570_eng.pdf. Accessed 30 August 2010.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent views of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Charania, M.R., Crepaz, N., Guenther-Gray, C. et al. Efficacy of Structural-Level Condom Distribution Interventions: A Meta-Analysis of U.S. and International Studies, 1998–2007. AIDS Behav 15, 1283–1297 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-010-9812-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-010-9812-y